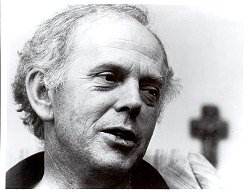

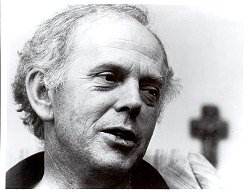

MALCOLM WILLIAMSON - a 70th Birthday Tribute

by Paul Conway

Malcolm Williamson, Master of the Queen's Music,

Died on Sunday March 2nd 2003, aged 71

List of Works Photo

gallery

Photo credit John Carewe courtesy

of Boosey&Hawkes

Malcolm Benjamin Graham Christopher Williamson was born in Sydney

on November 21st 1931. He studied piano, violin and

french horn at the Sydney Conservatorium. Later, his composition

teachers were Sir Eugene Goosens, Erwin Stein (an ex-pupil of

Schoenberg) and Elizabeth Lutyens. Since the age of 18 he has

lived in Britain, though frequently visited other European countries

(encountering the music of Boulez in Paris) and America. In

his early years in Britain he worked in a publishing house and

as an organist and choirmaster before concentrating on composition.

As a young aspiring composer he experimented with the 12-tone

serial technique, became interested in medieval music and discovered

an affinity with the compositions and philosophy of Olivier

Messiaen not long after his conversion to Catholicism in 1952.

Thus, when his own music began to be recognised as a powerful

individual voice in the mid-1950s, he had already immersed himself

in various trends and influences. From 1958 he began to earn

a living as a night club pianist and this had a major impact

on his attitude to popular music which he has always produced,

sometimes simultaneously with intensely serious religious works,

a juxtaposition which has occasionally baffled his critics.

Malcolm Williamson's many compositions range from full scale

operas, symphonies, choral, vocal, chamber and keyboard works

to church music, film music and music for children. In the 1950s,

it was the help of Sir Adrian Boult and Benjamin Britten that

enabled his first works to be published. A steady flow of commissions

followed. In 1975 he was appointed 19th Master of

the Queen's Music, succeeding Sir Arthur Bliss and in 1976 he

was created CBE. Latterly, due to ill health, his output has

become less prolific yet 1995 saw a beautiful song cycle for

soprano and orchestra premiered at the Proms: "A Year of Birds"

is an evocative song cycle to poems by Iris Murdoch. Though

his interest in writing occasional pieces for the Royal family

has clearly waned over the last two decades, he was moved to

write a work in memory of his friend Sir Harold Wilson which

received its first performance in 1995. With such a rich and

diverse body of work to choose from, it is difficult to single

out individual works. The following selection is a mixture of

significant compositions in Malcolm Williamson's development

as a composer and examples of his best work in all genres.

Malcolm Williamson's First Symphony is

entitled 'Elavimini' (the Latin for 'be ye lifted up' taken

from Psalm 24). It was written between 1956 and 1957 and is

scored for 2 flutes (piccolo), 2 oboes (cor anglais), 2 clarinets

(bass clarinet), 2 bassoons (contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets,

3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings. 'Elevamini

' is an astonishing achievement for a composer in his early

twenties: apart from the technical skills evident in the scoring

and architecture of the symphony, the emotional depth and spiritual

maturity apparent in the personality behind the work is remarkable.

Created in response to the death of the composer's maternal

grandmother (the score is inscribed 'in memoriam M.E.W.'), the

piece takes the form of a requiem with a light, lively middle

section encased by two probing Lentos (a structure he would

repeat in his equally profound Violin Concerto of 1964). The

symphony lasts about 25 minutes.

The Lento first movement is divided into

four parts. The opening section begins with imposing dissonant

tutti chords representing the passage in Psalm 24 where the

gates of brass of the New Jerusalem are raised to receive a

new soul. These chords make an arresting opening to the symphony,

resembling the 'Fire' chords which recur in the Ritual Dances

from Michael Tippett's 'A Midsummer Marriage'. The Dances were

first performed in 1953 and the opera in 1955 and the 'Fire'

chords may possibly have found their way into Malcolm Williamson's

imagination. The first section of the Lento continues

with the progress of the soul depicted by the string section

in hushed interweaving counterpoint. An important falling motif

in the first violins emerges five bars after fig 1. It bears

a striking resemblance to a haunting descending motif on cor

anglais in the final movement of Mahler's Ninth Symphony just

before the start of the closing Adagissimo section and

the valedictory nature of such an association is poignantly

appropriate. Stomping lower string chords and semitonal clashes

in the violin parts create a mounting feeling of restless anguish.

The 'Mahler' motif is repeated ever higher in the first and

second violins until they ascend to the very edge of inaudibility.

The second section contains memorable vaulting, arch-like arpeggiated

woodwind figures over scrunched semitonal conflicts on violin

chords. The third section (largo marziale) is a solemn funeral

march which rises in fugal complexity and increases in intensity

as instruments are added to the texture. At the climax of this

section, the 'gates of brass' chords reappear (quadruple forte,

sounding like the Last Trump). The fourth and final section

of the first movement, Andante lento, provides serene

and hushed repose. The 'gates of brass' chords are transfigured

into a rhythmic motif which appears on violins and bassoons

both in their highest registers. The 'Mahler' motif returns

as a flute solo, espressivo. The movement ends with muted strings

sounding the 'gates of brass' from afar.

If the Allegretto central movement is

meant to depict the joy of the Angels and the Saints at the

arrival of a new soul, they also resemble latter-day Saints

as there is a distinctly Coplandesque quality about this movement

with its dancing arpeggios. These arpeggios are a transformation

of the arch-like woodwind figures from the start of the previous

Lento movement's second section, whilst the 'gates of

brass' chords are transmuted into punchy, accented tutti chords

that momentarily stem the flow of the undulating texture. The

complexity of the interweaving lines of the preceding movement

is replaced by a more straightforward tonality and the time

signature is an unchanging 3/8, though cross rhythms lend a

syncopated feel to the movement. The Trio section takes the

form of a long-breathed benediction for the violins and divided

cellos over which the flutes continue the scherzo theme. The

scherzo reprise is varied, the textures thinning out until three

final, emphatic tutti strokes.

The Finale, Lento assai, is conceived

in terms of blocks of slow and fast sections though the rhythm

remains unvaried. The slower section consist of an evermore

insistent muted trumpet call cutting through multi-layers of

Messiaen-like woodwind lines. The faster sections echo the first

Danse Sacral from Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, an apt reference

as the ritual and dance elements of the Stravinsky ballet score

complement Elevamini 's ecstatic dances of the angels and saints

as the soul is accepted into their celestial number. The 'gates

of brass' chords return, leading to an extended dance section

which has something of the cosmic explosiveness of a symphonic

movement by Robert Simpson. The side drum beats out the predominating

dance rhythm of the Finale and the work ends with the divided

string section playing a seemingly endless chord stretching

out into Infinity.

The importance of Elevamini in the Williamson

oeuvre cannot be overstated. It was the first large-scale orchestral

composition of his maturity as a composer and the piece reveals

the Williamson style burgeoning out of his early influences

- the Second Viennese School, Stravinsky and Messiaen, with

a dash of Britten and Tippett. The idea of a first symphony

based on such solemn inspiration and its unusual slow-fast-slow

sequence of movements may have militated against the success

of Elevamini , though John McCabe adopted a similar structural

layout of movements for his elegiac First Symphony in 1965 without

harm. Perhaps in mid-1950s Britain, conservative elements in

the Musical Establishment were not prepared to accept Williamson's

vision. In any event, the work was not taken up until Sir Charles

Groves and the RLPO nearly 20 years after its composition when

they recorded it on an EMI LP (SLS 5085), a performance

which deserves an immediate CD release. Ironically the work

enjoyed critical acclaim on the release of the LP not accorded

to the Williamson works of the late 1970s. Today, the symphony

stands up as an astonishingly original first example in the

genre, serving notice that Malcolm Williamson was not going

to be a traditional symphonist!

One of the composer's most approachable orchestral

works, the Overture 'Santiago de Espada' of 1957 is a

delight and would make the perfect curtain raiser to any concert.

Its format adheres closely to the traditional Overture with

a martial introduction given to timpani and percussion leading

to the Allegro first subject, a rousing, emphatic rallying

cry for trumpets, as chevalric in tone as the Agincourt Overture

by Walter Leigh or the music for Henry V by Walton. This first

subject theme, suggesting St James inspiring the Spaniards to

victory in battle is elaborated in a syncopated, jazzy style:

typical Williamson. A ritardando leads to the regal second subject,

a noble theme depicting St James lying in a marble ship. This

melody, first heard on second violins and joined by first violin

with a solo horn descant, is a greatly deconstructed, serene

version of the first subject. The first oboe continues the theme,

followed by trumpet supported by first oboe and clarinet with

piccolos, flutes and violas giving out a celebratory peal of

bells. The Allegro first subject bursts in along with

the percussion from the introduction. Soon the horns intone

the second subject on top in dazzling counterpoint, reaching

a triple forte climax before the percussion powers the

overture to a spectacular conclusion. Perfectly paced and thrillingly

scored, the Santiago de Espada Overture is sorely neglected

by concert promoters and record producers alike - an oversight

for which the music loving public is all the poorer. It too

was included on the deleted EMI LP SLS 5085 with the

RPLO conducted by Sir Charles Groves.

The Piano Concerto no 2 (1960) represents

the composer at his most brilliantly playful. It is scored for

piano and strings only and is dedicated to Elaine Goldberg.

The first subject of the opening Allegro con brio

has a 'cat and mouse' quality about it with the piano as scuttling

mouse and the strings as the pouncing cat. The second subject

(in fourths) is a witty amalgamation of the oriental and the

tango. It recurs near the end of this brief movement, fortissimo

and tenuto, ironic and magnificent, before the piano

and second violins shoot up (via some dominant sevenths) to

a dead halt. The following Andante lento begins with

muted strings ushering in an extended canon of solemn beauty.

The piano joins in. There is a brief pause and a series of ethereal

broken chords introduce the second subject, characterised by

rippling piano arpeggios and tutti upper strings in a chant-like

melody. The piano takes up the chant, building a crescendo of

considerable intensity which leads to a brief but brilliant

cadenza. The first subject, now bathed in a half-light provided

by tremolo upper strings, returns in the lower strings.

The piano takes it up and the textures become increasingly delicate

until…the Allegro con spirito Finale bursts in with

all the brilliance of A major. If the first movement was 'Tom

and Jerry', this is outright slapstick comedy with a Keystone

Kops first subject and an 'off-key' waltz for a second subject.

The first subject gains a Rachmaninov-like string theme which

is taken up by the piano and gains some triplets. After a reprise

of the opening material, the 'Rachmaninov' theme is given the

full Romantic treatment where it rises above the level of its

cliché status as surely as the ending of Malcolm Arnold's

Fifth Symphony transfigures its own 'cliché theme. There

is a mad dash for the finishing line.

The Shostakovich-like wit on display in the

outer movements would make this concerto one of the most enjoyable

in the repertoire. Sadly, of course, it isn't in the repertoire,

at least in Britain, which is unaccountable and a great shame.

Displaying the same raucous good-humoured fun as that of most

of the Malcolm Arnold concerti, the Williamson Second Piano

Concerto needs to be rescued from its undeserved obscurity and

brought before a public who will be amazed to find that so much

fun can be had from a late-20th Century concerto.

The beautiful central Andante provides a perfect contrast

and ensures the frolics do not become tiresome - a moment of

deeply felt calm between two circus acts of infectiously cheerful

vulgarity. The Piano Concerto no 2 was released on a long-deleted

EMI LP EMD 5520 with Gwenneth Prior as soloist

with the English Chamber Orchestra under Yuval Zaliouk. The

LP also included the Concerto for Two Pianos and Strings

of 1972 and the string orchestra version of the Epitaphs

for Edith Sitwell (1966).

In 1960, the composer wrote his first film score

for Hammer Productions: The Brides of Dracula, the company's

first sequel to the international successful 'Dracula' of 1958.

The composer showed himself to be adept at creating a powerfully

atmospheric soundtrack without drawing attention away from the

film's action. The opening title seqeunce is available on a

GDI CD (GDICD002). The composer returned to Hammer

for two more films, Crescendo (1969) and The Horror

of Frankenstein, though neither of these productions had

the style and prestige of the initial project. The title sequence

of Crescendo is available on GDICD005 and the music for

The Horror of Frankenstein's opening credits appears on GDICD011.

The latter film is also available on Video (Warner Home Video

Horror Classics S039135). Twenty four years after The Brides

of Dracula, Williamson found himself supplying the music for

another Peter Cushing film, The Masks of Death. Cushing

and John Mills make a somewhat ancient Holmes and Watson in

this Tyburn production, but the score is first rate. The final

march as Holmes drives up to Buckingham Palace in a coach and

horses to receive the "signal honour" of his knighthood is splendidly

Elgarian with a dash of Walton thrown in. It was used again

for the title theme of Peter Cushing's life story 'A One-Way

Ticket to Hollywood' and is proof that Malcolm Williamson's

melodic gifts have never deserted him. The Masks of Death is

available on an Art House Production video (AHF 2027)

and One-Way Ticket to Hollywood is released by Encore Entertainment

(encore@enc.co.uk).

Malcolm Williamson originally designated his

Sinfonia Concertante as Symphony no 2, but owing to the

concertante nature of the solo instruments of three trumpets

and piano as distinct from the string orchestra, he changed

the title. Begun in 1958 and finished in 1961, this piece is

dedicated to the composer's wife. Each of the three movements

bears a religious superscirption. The first movement, 'Gloria

in excelsis Deo', begins with a chanting motif played by the

piano over held three-part trumpet chords. After their imposing

opening statement, the strings initiate a driving pulse. This

pulse continues throughout the movement which is in sonata form.

The central Andante lento remains in 3/8 throughout and

is constructed in one long-breathed arc, building up in complexity

and richness only to fall away to a restful conclusion. The

Presto Finale harps on F sharp, exploiting the bright

colours of trumpet, piano and strings. A Rondo with variations

to its recurring material, the Presto contains a piano

cadenza with trumpet interjections. A slow epilogue almost achieves

the status of another slow movement, reviewing the harmonic,

rhythmic and colouristic elements of the work and bringing the

piece to a satisfying close. The Sinfonia Concertante featured

on the EMI LP SLS 5085 with Martin Jones as pianist

with the RLPO under Sir Charles Groves.

Commissioned by William Glock for the Proms,

the Organ Concerto of 1961 is dedicated to Sir Adrian

Boult who conducted the first performance. A celebration of

the dedicatee, the work's unchanging time signature in each

of the three movements was allegedly a response to a plea from

Lady Boult to refrain from a surfeit of metric variety. To compensate

for this, Malcolm Williamson concentrates on rhythmic diversity

with the use of cross rhythms in particular characterising the

piece. It emerges as one of the most life-affirming and idiosyncratic

of the Williamson orchestral works. The first performance of

the concerto took place at the Royal Albert Hall on 8th

September 1961 with the London Philharmonic under Adrian Boult

and the composer himself as soloist.

The opening movement begins with a cadenza (Andante

quasi recitativo) on the notes ACB (the thematic germ for

the whole concerto) for timpani over bass drum pointed up by

harp and organ chordal eruptions from the brass. The character

of the movement is that of a ritual dance or even a Dance of

Death with the soloist as a gleeful Satan. Throughout the movement,

the majority of the strings play pizzicato, only four violas

and two double basses being permitted to use their bows. The

woodwind section is silent throughout.

The central Largo sostenuto is scored

for strings alone. It provides a necessary core of repose in

an otherwise highly exuberant and extrovert work. The Largo

is characterised by an extended unison melody for strings as

well as divisi string writing. An extended and challenging

organ cadenza follows, adding necessary structural balance in

that it lends weight to the Allegro Finale to match that

of the first movement.

The Finale marks a return to the volatility

of the opening movement, accumulating motifs and effects from

earlier sections of the concerto. It is scored for full orchestra

and the woodwind are finally allowed full reign. A climax is

reached in which the main motif of the work (ACB) reaches its

apotheosis in a broad and noble melody, capping the concerto

with an affirmative and jubilant conclusion. The Organ Concerto

was recorded in 1975 by Lyrita with the composer as soloist

with Sir Adrian Boult and the LPO (SRCS 79). Sadly this

recording, along with so many other riches in the Lyrita vaults,

is currently unavailable.

The Third Piano Concerto (1962) was commissioned

by the Australian Broadcasting Commission and is dedicated to

John Ogdon who gave the first performance of the work with the

Sydney Symphony Orchestra under Joseph Post. The Allegro

first movement begins with the chordal main theme on solo piano

over accompanying horns and strings. The song-like second subject

is a reconstructed version of the first subject. It is heard

on clarinet, then piano and finally divided amongst the orchestra.

This opening movement is entitled 'Toccata' owing to the diversity

of touch required of the pianist and also because of the driving

rhythms which permeate it. The following Scherzo falls into

four parts: the first is a fluent and ascending melody; the

second an oppressive dance in 10/6; the third a return to the

first section and the fourth section the culmination of the

movement where all the previous material collides and reaches

a violent apotheosis. The slow movement, marked Molto largo

e cantando resides within a flowing 3/2 time signature.

Inward-looking, this weighty movement is the emotional core

of the Concerto, its opening cantillena for piano establishing

the mood of restrained lamentation whilst the shattering brass

motifs introduce a more agonised form of grief, close to raging

despair. In the cadenza, calm is restored before the daylight

breaks in with the Ben Allegro Finale. The orchestration

and metres of the first movement are recalled and the soloist

goads the orchestra with its ebullience restored towards ever-greater

feats of rhythmical dexterity. Metrically inventive and melodically

attractive, the concerto finds the composer at his most uninhibited.

It was coupled with the Organ Concerto on the Lyrita

release SRCS 79 when the composer played the solo part

with the LPO under Leonard Dommett.

Malcolm Williamson was asked to write an organ

piece for the new cathedral at Coventry in 1962. The resulting

work, Vision of Christ-Phoenix was inspired by the sight

of the rebuilt cathedral constructed upon the ashes of bombed-out

remains. The Coventry carol beginning "Lullay, Lulla, thou little

child" is used as the basis for a passacaglia and a set of variations.

The three sections portray the destroying flame, the second

section peace and hope whilst the third and final section reflects

the triumphant Resurrection with Christ as a pheonix rising

from the ashes. The piece has been recorded in a splendid performance

by Kevin Bowyer on Nimbus (NI 5509) along with

the original version for organ of Williamson's Epitaphs for

Edith Sitwell (1966).

The Display (1963) is a narrative ballet

devised by Robert Helpmann and commissioned by the Australian

Elizabethan Theatre for the 1964 Adelaide Festival of Arts.

The story centres on a male bird's wooing of its mate. At the

ballet's conclusion, the girl, desolated by the violent events

in the forest, gives herself up to the bird's advances. A Concert

Suite from the complete ballet was included in the EMI

release SLS 5085. The Sydney SO was conducted by John

Hopkins.

Malcolm Williamson's Violin Concerto

was commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin for the Bath Festival in

1964. Dedicated to the memory of Edith Sitwell, who died during

the composition of the work, the concerto consists of two grieving

slow encasing a central scherzo whose satirical bite suggests

a portrait of the dedicatee. The concerto was first performed

by Yehudi Menuhin and the Bath Festival Orchestra in the Assembly

Rooms, Bath on 15th June 1965.

The opening movement, Adagio e sostenuto,

begins with the imposing and tragic first subject (a descending

scale over an undulating accompaniment). The solo violin rises

out of the violin section to perform an extended solo passage.

This is the concerto's sole cadenza and it leads directly to

the second subject, an uneasy lament in 10/4 time. If the first

subject is a public declaration of mourning, the second subject

has the intimacy of private grieving. It is a haunting, nostalgic

theme, slightly sentimental - like a Victorian ballad such as

Edith Sitwell would have heard in her youth. The development

section pits the sorrowing solo violin against the full-throated

sobbing of the tutti orchestra whilst the recapitulation of

the much transformed first subject features severe technical

tests for the soloist with its double and treble stopping passages

over harp and string accompaniment. The second subject returns

largo tranquillo, transformed into a gentle requiem for

a bygone era. It brings the movement to a hushed close with

the musical argument unresolved.

The central Vivace is an acerbic scherzo

- music of the night and second cousin to the central spectral

Scherzo of Mahler's Seventh Symphony. Fleeting as a nightmare,

its gawky, martial main theme is occasionally interrupted by

a rich, soaring melody which again seems parodic in intent.

A direct tribute to the irony and brilliance of Edith Sitwell's

verse, the world of Façade is not far away (Walton himself

is said to have admired this concerto). The Presto coda

brings the movement to a spiky, spirited conclusion.

The Adagio molto Finale is a slow threnody,

elegiac in character. A tender and poignant melody for solo

violin ascends to celestial heights over a throbbing, kaleidoscopic

orchestral accompaniment. Three tutti hammer blows of Fate divest

the work of its remaining energy and the concerto ends in dignified

resignation, accepting the loss it has previously railed against.

As the soloist soars away, fading to a triple piano conclusion,

the inevitability of the passing of life is memorably and unsentimentally

caught in these final bars. The Violin Concerto is currently

available on CD (coupled with the Panufnik and Lennox Berkeley

violin concertos with Yehudi Menuhin and the LPO conducted by

Sir Adrian Boult (EMI 7243 5 66121 2 9).

The three-movement Sinfonietta for orchestra

was commissioned by the BBC for performance at the inaugural

concert of the introduction of Radio 3. It was first performed

on March 21st 1965 by the New Philharmonia Orchestra

conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. Ten years later, Sir Frederick

Ashton created a ballet from the score for the Royal Ballet

at Covent Garden and for this production, the composer added

a Prelude and reduced the brass scoring. The absence of any

timpani in the score is compensated for by an array of percussion

as well as harp. The short Prelude of the 1975 ballet version

features a mystical and creeping dialogue between woodwind and

brass. In the very last bar of the Prelude, a dramatic and drastic

crescendo heralds the arrival of the first movement proper -

a lively and motoric Toccata in modified sonata form. The first

subject is the opening string motif with short replies from

the brass section. The extended second subject begins in the

bass but becomes a memorable theme for violins derived from

the first subject. An elliptical recapitulation leads to a short

coda which ends with a leap into the stratosphere.

The central Elegy is tripartite in structure.

Firstly, a highly evocative passage for divided solo strings

in harmonics with harp sounds against flutes. Under this, a

broad theme rises from a solo double bass. A counter-statement

on strings with oboe assuming the double bass theme leads to

the second main section - brass and woodwind intone a funeral

march which builds to a powerful climax in the aftermath of

which the third and final section flickers into life. This passage

juxtaposes aspects of both previous sections. The brass and

woodwind rhythm is transfigured into a convulsive pulse with

the woodwind assuming the flute's melody above the double bass

theme now given out by solo trombone.

The concluding Tarantella is a whirligig of

almost frenetically high spirits. A whirling dervish of a movement,

the contrasting section of its Rondo structure provide fleeting

contrasts but the sheer energy of the main dance motif overrides

all and powers the Sinfonietta on to a bravissimo conclusion,

crowning one of its composer's most immediately enjoyable works.

It was recorded by the Melbourne SO under Yuval Zaliouk for

RCA (GL 40542) on a deleted LP.

The Five Preludes for piano (1966), premièred

at the 1966 Cheltenham Festival, were the product of a commission

for a set of piano pieces by Antonietta Notariello. The titles

for the preludes are taken from William Wordsworth's sonnet

'Upon Westminster Bridge' - Ships, Towers, Domes, Theatres and

Temples. Each prelude evokes a different aspect of London (the

London of 1966 rather than that of Wordsworth's day) and explores

a different pianistic technique. In the opening 'Ships', an

undulating figure for the left hand suggests the sea whilst

the wide melodic range of the piece (it is scored for treble

and two bass clefs!) and the hushed dynamics (mostly ranging

from piano to triple piano) suggests a ship in full sail on

clam waters. In 'Towers', powerful chords for the left hand

depict the firm base of tower blocks, whilst the flowing right

hand phrases point in more intricate details. The central prelude,

'Domes' includes right hand grace notes which paint a picture

of vaulting domes. Something of the bravura performances of

the stage are recalled in 'Theatre' in the heavily accented

chordal passages for right hand, marked brilliante which

recur throughout the prelude. The main theme is slightly jazzy,

suggesting the smell of greasepaint and a touch of the Music

Halls. The final prelude, 'Temples' makes a grand, imposing

conclusion, paying tribute to the architectural splendour of

such sacred buildings. The Preludes were recorded by the composer

on a deleted Argo LP ZRG 682.

Also in 1966 came the great opera in three Acts The Violins

of Saint Jacques with a libretto by William Chappell based

on the novel by Patrick Leigh Fermor. It was premiered at Sadler's

Wells Theatre on 29th November 1966. The cast included

April Cantelo as Berthe, Jennifer Vyvyan as the Countess de

Serindan and Owen Brannigan as the Count de Serindan. The Sadlers

Wells Orchestra was conducted by Vilem Tausky. The opera tells

the story of the Island of Saint Jacques in the Carribean which

was destroyed with all its inhabitants by a volcanic eruption

at the start of the 20th century. The score is one

of its composer's most enjoyably eclectic, ranging from Brittenesque

seascapes and Bergian Expressionism to Sullivan-like melodies.

There is also a presage of Andrew Lloyd Webber in the arias

"I have another world to show you" and "Each afternoon when

the cooling breezes swoon and die". Coincidentally, more than

twenty five years after the opera was first performed, Malcolm

Williamson would sing the praises of Lloyd Webber's "Sunset

Boulevard" - perhaps the songs in that musical triggered memories

of his own operatic melodies. The opera encompasses many changes

of mood from the tropical suppressed passion of the first Act

to the Candide-like wit and charm of the second Act with its

lilting rhythms. The atmosphere a Savoy operetta at this point

is highlighted by the character of Captain Henri Joubert, an

over-dressed foppish dandy. One can imagine John Reed playing

such a character with little difficulty. Of the composer's many

operas, none deserves revival more than this one. Its abundance

of drama and good tunes should endear it to a wide audience.

The Pas de Quatre of 1967 was commissioned

by the New York Metropolitan Opera for their summer festival

at Newport, Rhode Island. The piece is scored for flute, oboe,

clarinet, bassoon and piano and adheres to the structure of

a classical Pas de Quatre. The opening sonata is scored for

full ensemble. There follows a variation for flute and piano,

a slow, intense Pas de Trio for bassoon and piano, a variation

for flute and oboe and a seduction Pas de Deux for clarinet

and piano. The concluding coda is virtuosic and culminatory,

referring fleetingly to previous themes. The Argo LP

ZRG 682 includes a performance of the Pas de Quatre by

the Nash Ensemble and the composer at the piano.

The three-movement Piano Quintet (1968)

for piano and strings was commissioned by the Birmingham Chamber

Music Society. It is cast in three movements of unequal proportion:

an extended Allegro molto is topped and tailed by brief Adagio

movements which anticipate and reflect on, respectively, the

material of the central movement. The first Adagio is chilling,

on the edge of audibility, inhabiting the same unearthly soundworld

as the Finale of Vaughan Williams' Sixth Symphony. Acerbic and

joyous by turn, its brevity only serves to heighten its capacity

to disconcert. The central Allegro molto is the substantial

heart of the work. It displays some of the characteristics of

both scherzo and rondo in that each passage spawns succeeding

variants of itself. Successive writhing chromatic lines in the

strings are broken up by wide-ranging figurations in the piano.

The tonal gamut is traversed throughout the movement. The concluding

Adagio returns to the slow-moving progress of the first movement,

though here the atmosphere is one of serenity rather than unease.

The Quintet ends in peace, drained of energy, though the unsettling

mood established by the start of the piece is not entirely vanquished.

The Nash Ensemble and the composer recorded the work for Argo

(ZRG 682).

The song cycle 'From a Child's Garden'

for high voice and piano to words by Robert Louis Stevenson

was commissioned by the Cardiff Festival of 20th

Century Music and first performed by Robert Tear and John Ogdon

on 24th April 1968. The onomatopoeic sound of the

'birdie with a yellow bill' dominates the opening song 'Time

to Rise' and this fleeting figure recurs as a leitmotif in the

fifth song 'While Duty of Children' and the final 'Happy Thought'.

Four of the songs are written in a melodic, tonal idiom, 'The

Flowers', 'My Bed is a Boat', 'A Good Boy' and 'The Lamplighter'.

Some of the songs have onomatopoeic piano parts: as well as

the bird-like phrases of 'Time to Rise', other examples include

'Marching Song' with its stomping piano line, 'Where go the

Boats?' with flowing piano phrases suggesting an idyllic sunlit

river. 'Rain' is suggested by staccato droplets in contrasting

speeds in the piano part and 'From a Railway Carriage' (Allegro

molto) has quick alternating chords suggesting the regular movement

of the train with the scenery flashing by. A prime example of

Malcolm Williamson's gifts as a sympathetic setter of words,

'From a Child's Garden' is a charming song cycle. As I well

remember, it was a set work in the 1980 'O' Level Joint Matriculation

Board syllabus. Soprano April Cantelo recorded the work with

Malcolm Williamson as piano accompanist (ARGO ZRG 682).

The Second Symphony of 1969 was commissioned

by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra on the occasion of their

75th anniversary and first performed at the Colston

Hall, Bristol on 29th October 1969, conducted by

George Hurst. The symphony is scored for 3 flutes (piccolo),

3 oboes (cor anglais), 3 clarinets (bass clarinet), 3 bassoons,

4 horns, trumpet in D, 2 trumpets in B flat, 3 trombones, tuba,

harp, timpani, percussion (3 players: side drum, tenor drum,

suspended cymbal, tam tam, anvil, 2 pairs of bongos, tubular

bells, glockenspiel, vibraphone, celesta) and strings. Apart

from brief minor fluctuations and a couple of short allargando

passages, the initial tempo of lento moderato con rubato

is maintained throughout this concise 20-minute one movement

symphony. The long breathed first subject begins the work, falling

like droplets from the piccolos and flute, harp and divided

first violins over the bubbling stream of the nonuplets in the

strings. This 'droplet' theme is answered by an equally important

motto theme for brass incorporating a dotted rhythm. At letter

C of the score, the second subject begins. A theme for brass

with an accompanying descending figure in the woodwind initiates

an arc-like figure for tutti strings. If the first subject is

like water droplets in the calm before the storm, then this

is the storm itself. It is cut short at figure D when the first

subject returns, then breaks out again, this time in the woodwind

section. The first subject is speeded up. All these elements

are developed in the second half of the symphony. A climax is

reached at figure HH and in its aftermath the initial figure

returns. The work ends abruptly, the last droplet having landed.

Compact and closely argued, the Symphony no 2 is unquestionably

as individual as its predecessor yet as unlike that work as

one could possibly imagine.

The Icy Mirror is the title of Malcolm

Williamson's Third Symphony of 1972. It is scored for soprano,

mezzo soprano, 2 baritones, SATB chorus and orchestra (2 flutes,

piccolo, 2 oboes, cor anglais, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon,

double bassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, three trombones, tuba,

percussion (glockenspiel, xylophone, temple block, suspended

cymbal, tenor drum and side drum), harp, piano and strings).

A setting of a dramatic poem by Ursula Vaughan Williams, the

symphony was commissioned by Sir Arthur Bliss for the Cheltenham

Festival, where it was premiered on the 9th July

1972. The opening Adagio movement makes effective use

of a descending figure for harp which eerily depicts the Icy

Mirror of the title: "All history shows an icy mirror to man's

intellect". The central Presto movement is literally

a Dance of Death with swirling upper woodwinds sounding like

teeming maggots. The Adagio Finale is a moving threnody

in a post-nuclear age which builds to a powerful climax before

the work closes with ominous taps from the temple block. As

an example of the composer's gift for word setting this could

hardly be bettered: at the words "trumpets in the sky" in the

Finale, for example, the composer avoids the obvious and uses

a staccato figure in the woodwinds creating the appropriate

effect of celestial distance. The forces taking part in the

world première included Jennifer Vyvyan (soprano), the

Cheltenham Bach Choir, the Cheltenham Festival Chorus and the

BBC Northern SO with conductor John Hopkins.

The Fourth Symphony was written in 1977.

It was commissioned by the London Philharmonic Orchestra to

celebrate the Queen's Silver Jubilee. Unfortunately it has never

been performed. The symphony is a substantial twenty-eight minute

work for large orchestra: three flutes, piccolo, three oboes,

cor anglais, three clarinets, bass clarinet, three bassoons,

double bassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones,

tuba, timpani, three percussion players, harp and strings. There

are three movements: The Birth of the World (Largo); Eagle (Allegro

vivo) and The Prayer of the Waters (Lento). The score is dedicated

to Her Majesty the Queen. Along with this year's fellow 70th

birthday celebrant Anthony Hedges' second symphony of 1997,

this work desperately warrants performance and recording.

Of the composer's large scale choral works,

none is more impressive than his Mass of Christ the King

(1978). The piece was jointly commissioned by the Three Choirs

Festival and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra to celebrate The

Queens' Silver Jubilee and the mark the 250th Three Choirs Festival.

The whole work is dedicated to The Queen but as Benjamin Britten

died on the day the composer began the Agnus Dei, Williamson

asked if that movement could be dedicated to Britten. The work

had a long gestation: sketches for a setting of the Feast of

Christ the King were begun in 1953 and the composer returned

to the idea from time to time until the Three Choirs Commission

urged him on to complete the setting as a large scale work.

The first notes were written at the end of 1975 and the full

orchestral score was finished two and a half years later. The

Latin text is taken from the Old and New Testaments as well

as from the early years of Christianity. The composer has said

that when composing it, he was less aware of the music of his

own time than that to Hebrew music and that of the Middle Ages.

It is this archaic quality this which gives the Mass its special

character. The work takes the form of a continuously evolving

symphonic movement in sixteen parts with set pieces in the structure

finally finding their place in the apotheosis that concludes

the Mass. The piece calls for two sopranos, lyric and dramatic

as well as tenor and baritone soloists. There is an echo choir

interlocked with a large chorus. The Ordinary of the Mass is

interspersed with the hymns, psalms and other texts proper to

the Feast of Christ the King in the manner of the poems set

within Britten's War Requiem. Some of the settings, such as

the Introitus, are quite operatic, illustrating the composer's

admirable lack of distinction between the secular and the sacred,

the "highbrow" and the instantly communicative. This one of

several works by Malcolm Williamson which is absurdly overdue

for a CD release.

Commissioned from Malcolm Williamson by the

Old Creightonians (Kilburn Grammar School Old Boys' Association)

for the Brent Youth Orchestra for its tenth anniversary year,

the Fifth Symphony was completed early in 1980 and first

performed at a St George's Day Concert on Wednesday 23rd

April of that year. The première took place at Brent

Town Hall with the Brent Youth Orchestra conducted by John Michael

East. The symphony was the result of a dual inspiration: the

composer's association with Youth orchestras and the story of

Saint Bernadette and the Apparitions in the grotto at Lourdes.

In her local dialect, the uneducated Bernadette Soubirous could

only describe what she saw as AQUERÒ, meaning approximately

the same as 'çela' in French or 'that thing' in English.

The symphony may be seen as a hymn to the importance of education:

as a result of St Bernadette's account of events she was found

to be highly intelligent and given a school education. The Fifth

Symphony is written for young players with due regard for their

varying skill but also stretching them in matters of technique

and general musicianship. The twenty-four minute work is scored

for 2 flutes (piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4

horns, 3 trumpets, 2 tenor trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani,

percussion (4 players: side drum, tenor drum, bass drum, 2 pairs

of bongos, triangle, small and medium suspended cymbals, tam

tam, high, middle and low gongs, tubular bells, xylophone, vibraphone,

glockenspiel) and strings.

The Symphony no 5 was originally cast in two

movements, the first a Credo, a statement or commitment, and

the second a meditation on the Apparitions. As the work progressed,

Malcolm Williamson realised that the ideas of commitment and

meditation were implicit, each in the other. Thus, the piece

became a one-movement symphony in the fashion of his Second

Symphony. The time signature of 5/8 is unwavering, but complex

rhythmic patterns contradict its pulse. The time signature,

therefore becomes more of a point of reference whilst encouraging

a degree or flexibility from the orchestra and conductor in

performance. The work begins and ends in F sharp, more the tonal

centre than a traditional tonic note. The symphony is an organically

developing drama of ideas. The start of the work with its soft

high strings suggests a sunrise in the Pyrexes. The horns play

a long chant-like melody. After these forward-looking elements

is a circular figure for flutes and glockenspiel and another

for clarinets and vibraphone, characterising the eternal and

celestial revolving above the earthly dynamic. Two further elements

constitute the main material of the symphony: a sequence of

rich, slow chords suggesting the Apparition and a long wide-ranging

melody which refuses to fall conveniently into a harmonic cradle.

The first oboe intones a plainchant-like line suggesting the

praying Bernadette: 'Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison'. The string

section is frequently divided with parts of varying difficulty.

Every section is highlighted at one time of another. If the

symphony does not demand individual virtuosity, it does call

for more than usually precise sense of community from the players,

an appropriate demand from a work which celebrates the community

of shared musicianship rather than empty technical display.

1980 also saw two important works written as

a result of the composer's Royal title: Ode for Queen

Elizabeth and Lament in Memory for Lord Mountbatten

of Burma. The Ode was commissioned by the Scottish Baroque

Ensemble who gave the first performance at a private concert

in the presence of the Royal Family on 3rd July 1980

at the Palace of Hollyrood House. The public première,

also given by the Scottish Baroque Ensemble, took place on 25th

August 1980 at Hopetoun House, Edinburgh. The work is dedicated

to Her Majesty the Queen Mother on the occasion of her 80th

birthday. It is divided into five movements: Act of Homage;

Alleluia; Ecossaise; Majesty in Beauty and Scottish Dance. The

eleven-minute Lament is dedicated to Leonard Friedman and the

Scottish Baroque Ensemble who gave the first performance on

5th May 1980.

The Sixth Symphony (1981-1982) is a massive

one-movement work, divided into fourteen sections, written for

the orchestras of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. An

Australian musical journey, each section bears an inscription

from the text of the Mass, making the symphony a liturgical

as well as a geographical odyssey. The symphony was originally

played by seven Australian orchestras to celebrate the 50th

anniversary of the ABC. Each of the fourteen sections was recorded

separately and broadcast complete throughout Australia. Future

performances could use just a single orchestra and Christopher

Austin of the Brunel Ensemble has already indicated his interest

in such a project. The Symphony no 6 is scored for a massive

orchestra: four flutes, piccolo, four oboes, cor anglais, four

clarinets, bass clarinet, four bassoons, double bassoon, six

horns, four trumpets, four trombones, two tubas, timpani, six

percussion players, harp, piano, organ and strings. At nearly

forty-five minutes, this is one of the composer's most substantial

orchestral works from the 1980s. It reminds the listener that

Stravinsky and Messiaen were formative influences on Malcolm

Williamson since the soundworlds of both the Rite of Spring

and the Turangalila Symphony are recalled near the end of the

symphony.

The Seventh Symphony (1984) was commissioned

by Alexandra E Cameron for the 150th Anniversary

of the State of Victoria. Dedicated to Derek Goldfoot, it is

written for string orchestra and, like its predecessor, takes

Australian landscape and history for its inspiration. The Symphony

no 7 received its première on 12th August

1985 by the Chamber Strings of Melbourne under Christopher Martin

at Irving Hall, Lauriston Girls' School, Melbourne. It is cast

in four movements: a tightly argued Andante-Allegro vivo-Andante

is followed by an Allegro Molto, obsessed with its woozy

opening theme. An extended Andante juxtaposes string

quartet textures with tuttis in the manner of the Tallis Fantasia

(the tuttis sound remarkably Straussian in their amplitude)

and the symphony ends with a brief but upbeat Allegro maestoso

ma non troppo. The Symphony has been recorded by the

Brunel Ensemble under Christopher Austin in a committed and

characterful performance (Cala CACD 77005).

The beautiful five-minute Lento for Strings

was written in 1985 and dedicated to Paul McDermott. It was

first performed by The Philharmonia of Melbourne in the year

of its composition and has been recorded by the Mastersingers

and Alan Simmons on Carlton Classics (3036601172).

This valuable disc also includes the composer's Procession

of Psalms, Easter Choice, Agnus Dei, Jesu,

Lover of My Soul, Love's Redeeming Work is Done,

Harvest Thanksgiving, The World at the Manger

and Epiphany Carol.

1988 was Australian Bicentennial Year and Malcolm

Williamson wrote two big works to mark this anniversary. The

True Endeavour for speaker, chorus and orchestra is substantially

based on texts by Australian historian Manning Clark, whilst

The Dawn is at Hand is a five-movement choral symphony

derived from poems by Oodgeroo of the Aboriginal tribe Noonuccal.

Written to celebrate 50 years of the United

Nations Organisation, With Proud Thanksgiving had its

first performances in Geneva and Britain in 1995. A brief but

impassioned orchestral work, it consists of two main themes,

the first deeply troubled, sounding like a hymn tune half-remembered

in agitation, the second a triumphant brass fanfare. As the

composer was completing the work, news reached him of the death

of his old friend Lord Wilson of Rievaulx. The score is dedicated

simply "for Harold Wilson".

The sum of these diverse compositions is a considerable

body of work from a strong and individual voice. Initially concentrating

on piano works, mainly with himself as soloist, Malcolm Williamson

has gone on to prove himself adept in every genre from light

music to church music, from chamber music to opera. Such prolixity

has meant the very occasional dud, but of which composer of

similarly prolific output from Telemann to Sir Peter Maxwell

Davies can this not also be said?

Though Malcolm Williamson has lived in England

for the best part of fifty years, a glance at the titles and

first performance venues of many of his works serves to confirm

that he is at heart an Australian. His last two symphonies are

steeped in Australian culture, to say nothing of the works for

Australian Bicentennial Year, 1988. As far back as 1965, he

spoke about his nationality at the Conference on Music and Education

in the Commonwealth held in the University of Liverpool, "…when

I think about it I am certain that my music is characteristically

Australian although I have never tried to make it so. We Australians

have to offer the world a persona compounded of forcefulness,

brashness, a direct warmth of approach, sincerity which is not

ashamed, and more of what the Americans call 'get-up-and-go'

than the Americans themselves possess." Certainly there is an

ebullience and a directness about Malcolm Williamson's writing

which sets him apart from most British composers.

The use of melodies in most of his compositions

bespeaks an artist who wants to communicate directly with his

audience. How tragic then, that, apart from regular performances

by Christopher Austin and the Bristol-based Brunel Ensemble,

his vast catalogue of works has been so rarely encountered in

this country's concert halls over the last couple of decades.

Recordings of his compositions are also pitifully few considering

the wealth of material to be found in his output. It is hard

to offer an explanation for this except that his champions,

apart from Christopher Austin, appear to have all died out and

no new ones taken their place. Nonetheless, I am convinced his

time will come. Composers who write genuine melodies and convey

some of the joy of living are rare and if they are not cherished

today may well be so in the future. In the meantime, I trust

the occasion of the composer's seventieth birthday year will

provide the necessary springboard for more performances and

recordings: they will reveal a deeply humane and life affirming

voice.

©Paul Conway 04/01