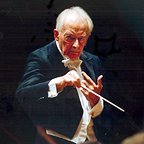

Günter Wand (1912-2002)

Günter Wand was the last of the great interpreters of the

19th-century tradition and his death, a week after his 90th

birthday, closes the chapter on a style of conducting which is now all

but extinct. A contemporary of Karajan, yet much closer to both Furtwängler

and Klemperer in the way he approached his chosen repertoire, he remained

something of an enigma to British audiences mainly because his choice

of works seemed so limited. In reality, this was a British truth because

in Germany he often programmed much broader repertoire.

He only really became known to many British concert-goers

in the early 1980s, firstly at Edinburgh and later at the Proms, his

last performance there in August last year in a typical Wand programme

of Schubert and Bruckner which I remember as one of the most memorable

of the season (and reprinted below). By this stage he already had to

be guided onto the podium but once there was unleashed, conducting with

a terrifying power which belied his advanced years. He may have been

bemused, even embarrassed, by the wild standing ovation which greeted

the closing bars of Brucknerís Ninth, yet it showed how much this great

conductor had captured the hearts of the British public.

Born in Elderfeld he studied piano and composition

at an early age and, like most of the great conductors of his generation,

started work in the opera house. In 1939 he became a staff conductor

at Cologne Opera, a city which remained musically close to him throughout

his career. After the war he was appointed music director and took on

the opera houseís concert orchestra which he continued to conduct for

another 30 years. In 1981 he became chief conductor in Hamburg, an orchestra

he built in to one of the finest in the world and which he brought to

the Proms in 2001: their playing was typically fabulous, the strings

the best I have ever heard in a live performance of a Bruckner symphony.

He also found a niche in Berlin, with the Philharmonic, in his last

years culminating in a number of recordings of Bruckner symphonies which,

although not necessarily better than his recordings made in Hamburg

and Cologne, display a level of artistry the orchestra rarely matched

with other conductors. Hearing his Bruckner with the Berlin Philharmonic

was indeed special since he brought a weight and sonority to the strings

which in my experience only Celibidache matched when he appeared with

the orchestra in 1992, 38 years after he last conducted it, in Brucknerís

Seventh.

The comparison with Klemperer and Furtwängler

is sometimes tangible. Wand widely admired Furtwänglerís conducting

but their styles were often poles apart and whereas the latterís Bruckner

had an inescapable sense of drama about it Wandís was often transparently

more imperious. Whilst Wandís Bruckner never became broader than it

could be (as happened with both Celibidache and Giulini) it still had

an immovable greatness about it, stoical in the Klemperer mould. And

like Klemperer, Wand in his early years devoted a great deal of his

attention to contemporary composers Ė Varèse being a particular

early passion, Ligeti a slightly later one. Both eventually turned away

from contemporary music although Klempererís repertoire always seemed

the wider.

Where Wand differed from both was in what he wanted,

demanded, from his orchestras. Wand was a perfectionist in a way that

neither Klemperer nor Furtwängler were. For Wand orchestral perfection

was a craft and his demands for rehearsal time, often eight or more

sessions, invariably meant only radio orchestras could afford the luxury

of his talents. This is partly why only the BBC SO were his chosen British

orchestra, and yet the results were palpable. Hear anyone of the broadcasts

of the BBC playing Bruckner under Wand and the results are intense and

impressive. Yet, like Celibidache, a Wand performance never seemed manufactured,

rising to levels of inspiration in the concert hall which belied the

length of time spent on the meticulous preparation behind it. Whether

it was Mozart or Schubert, Beethoven of Bruckner, or even Tchaikovsky,

a Wand performance had an immutable sense of freedom about it.

It is true that in later years he became temperamental

at rehearsals and gained a reputation for a virulent temper, often directed

at his colleagues. Like Klemperer he could be cantankerous, but also

like Klemperer he displayed a boyish charm which endeared him to people.

Orchestras loved working with him, and the results were never less than

magnetic. He appeared a simple man, yet like Klemperer had a taste for

the finer things in life, something which seemed almost at odds with

the great passion which became Bruckner.

With the death of Günter Wand, and the death

last year of the great Japanese conductor Asahina, Bruckner interpretation

now lies in the hands of a younger generation of conductors little interested

in the historical traditions which formed the interpretations of these

giants. His death closes the book finally on a golden era of conducting.

Marc Bridle

Günter Wand, conductor, born 7th

January 1912; died 14th February 2002.

Below we reprint a review of Wandís last UK concert

at the Proms on 24th August 2001.

PROM 46:

Schubert & Bruckner, NDR Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg, Günter

Wand, 24 August 2001 (MB)

Günter Wand, 90 next year, must now be the most

venerated conductor to stand on the rostrum of the Albert Hall. He emerged

from the wings, to open his concert with Schubertís Unfinished, gently,

and slowly guided by the arm. He moved onto the podium. The audience

clearly adore him as they welcomed him with a tumultuous roar few conductors

are lucky enough to receive at the close of a Prom, let alone before

a second of music has been played. At the close of Brucknerís Ninth

symphony the cheers and applause threatened to shatter the walls. Within

minutes the entire Albert Hall, packed to the rafters, was on its feet.

He returned three times. Extraordinary scenes that must almost be unique.

He chose to conduct the two greatest unfinished masterpieces

of Nineteenth Century symphonic music Ė yet the performances were utterly

complete, utterly compelling and of a time and a moment that we could

almost think to be extinct. The pacing was perfect in both works and

the magnificent NDR Symphony Orchestra offered playing that was fabulously

assured in technique. In the concert hall I donít think I have ever

heard better horn playing in a performance of the Ninth symphony than

we heard here Ė the very opening bars had all eight horns playing as

a single unified whole with every player breathing simultaneously, giving

precise dynamic weight to the notes. Throughout the entire work their

playing was faultless with even the most exposed writing played to perfection.

Woodwind were equally spellbinding (particularly a lamenting solo oboe)

and the strings (notably astonishing basses and cellos) were silken

in tone and capable of extraordinary purity in the upper register (even

if the first violins at bars 73-4 seemed overwhelmed by the fff

of brass and woodwind). Whilst the Albert Hallís notorious acoustics

were partly to blame for this I wasnít quite so sure about the strident

trumpets. Here the sense of balance seemed wrong. Yet, these were small

blemishes in a performance that seemed telescopically drawn, almost

as if Wand was building the bridge from the first movementís development

through to the coda of the third movement. Its span was undeniably impressive,

at tempos which seemed ideal. Particularly memorable was the Sehr

langsam section of the adagio (fig. M) through to bar 203 (end of

fig. Q). The gravity and weight of the climax, its collapse and the

resurrection of the coda were as complete as in any performance I can

recall.

The Schubert had uncommon weight yet was similarly

imposing. It was utterly memorable Ė a starter to a concert that will

long be remembered by those who were there. This was great music making.

Marc Bridle

Return to:

Music on the Web

Return to:

Music on the Web