Back

to Chapter 9

10

The Great and the Good

Playing for great, good, very good

and outstanding conductors – in the London Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic

and Philharmonia and elsewhere – Victor de Sabata, Bruno Walter, Charles

Munch, Thomas Beecham, Herbert von Karajan, Otto Klemperer, Lorin

Maazel, Colin Davis, Simon Rattle and many more.

What is it that makes us consider

some conductors ‘great’? What qualities do they possess that distinguishes

them from those we assess as good, very good or outstanding? Are those

we think of as great always dead? It seems to me that I remember artists,

composers and politicians being referred to as ‘great’ during their

lifetime. Perhaps because we now see them so often on TV and no longer

treated with the deference accorded them in the past we only think

of them as personalities or celebrities.

It is difficult to describe what it

is that a very few conductors have that makes us believe they are

great, yet we always recognise it when we are in its presence. We

sense that they are beyond the ordinary, have remarkable ability,

are in some way unique and have something extraordinary that separates

them from most of the rest of us. In some way they command our respect

and inspire us.

All the very best conductors, those

that my colleagues and I would consider great, combine the authority

and control I referred to in a previous chapter with the self-confidence

that allows them to respond to musicians in the orchestra who have

solo passages to play. This interplay between conductor and members

of the orchestra is one of the elements that leads to an orchestra

playing ‘better than it can’. The whole orchestra is inspired by the

conductor and by the playing of individual musicians in the orchestra.

Together, they combine to produce a great performance.

Because there are so many less good

than good conductors, orchestral musicians quite often feel that the

conductor stands in the way of them playing as well as they can. Every

musician who has taken part in a great performance will tell you that

this is only possible with a great conductor. However demanding he

may have been, and however extreme the demands one has to make on

oneself, the reward of taking part in a great performance is what

makes playing in an orchestra worthwhile. It is something very special.

One is enlarged by being part of something much bigger than oneself.

When one takes part in a performance

of a great piece of music with a great conductor in a fine orchestra

it is like being an eagle flying over Everest. At other times one

may only fly over Mount Blanc and that is very pleasant, too. However,

a lot of the time one is coasting along just above a range of hills.

Unfortunately, there are quite a number of occasions when one is at

ground level and, on the darkest days, even down in a valley.

From 1943 until 1979 it was my good

fortune to play with many of the very best conductors who came to

London: in 1943 in the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), from 1947

until 1960 in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) and finally in

the Philharmonia, from 1955 (while still playing in the RPO) until

1979. Over these years I also played with nearly all the other orchestras

in London, either as a deputy or an extra, in particular with the

London Symphony Orchestra (LSO).

I worked with several of the conductors

I refer to in more than one of these orchestras. The very best of

them obtained excellent performances from whichever orchestra they

were directing; other conductors, though very good, would get much

better results with one orchestra than another.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra

(LPO)

Towards the end of the 2nd World War,

from 1944, many conductors who had not been to Britain for a number

of years came to conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Some were

probably at the height of their powers and came with the advantage

of an established reputation. The first to arrive was Sir Thomas Beecham,

about whom I have written earlier.

No one I can recall had a greater

or more instantaneous effect on an orchestra than Victor de Sabata.

We knew very little about him other than that he was the musical director

at La Scala in Milan. On his arrival for his first rehearsal with

us he presented a rather romantic figure. He was quite tall, walked

with a limp and had the face of a Roman emperor. He wore a wide brimmed

black hat and wore his overcoat over his shoulders like a cape. Quickly

removing his hat and coat he stepped on to the podium. ‘Good morning,

Gentlemen. We start with Dvorak Symphony.’ We played through the whole

of the New World Symphony, from beginning to end as if it had

been a performance. It was tremendous. Incredibly volatile, his unique

conducting style at once electrified the orchestra. We had all played

this symphony many times before, but never quite like this. In fact,

I have never taken part in any performance of this work as rewarding

as those we did with him.

During the next few years de Sabata

conducted a wide-ranging repertoire with us and though he never used

a score, at rehearsals or concerts, his ear was so discerning that

I felt that even in the loudest orchestral passages he could hear

every note I played. At times he asked for such extremes of dynamic,

from the quietest pianissimo to the loudest fortissimo

that he quite frightened us. On one occasion, when we were recording

the Third Symphony by Beethoven with him, he demanded that the strings

play the spiccato passage in the third movement very quietly

indeed. When playing spiccato the violinist uses a bouncing

stroke of the bow to detach each note. Especially to do this very

quickly and very softly is extremely difficult. After several attempts

that did not satisfy him, one of the first violinists said, ‘Maestro,

it is getting worse – you are frightening us.’ de Sabata, eyes flashing

replied, ‘You are frightened, I am frightened – we must do it.’ He

remained a legend for all of us who played for him at that time and

one of a handful of truly great conductors

Bruno Walter was a man with a very

different personality. He was charming, courteous and urbane. His

approach to music was essentially lyrical. To play Mozart and Schubert

with him was a delight. I still have a programme for the concert he

conducted with us in January 1947 at the Royal Albert Hall – the Overture

Leonora No.3 by Beethoven, Mozart Symphony in G minor

No.40, and the Symphony No.9, the great C major,

by Schubert. Now, nearly sixty years later I remember it as one

of the great concerts I was fortunate to take part in. His tempi might

be thought rather slow by today’s standards but for me the ‘heavenly

length’ of this beautiful symphony by Schubert, though even longer

than usual in this performance, was quite wonderful.

It was with Bruno Walter that I first

played a Mahler symphony. At that time, in the 1940s, Mahler’s music

was practically unknown in Britain and was considered long and boring.

In the 1939 edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, in the article

on German and Austrian music Mahler is only mentioned in a paragraph

about the ban the Nazi regime imposed on the performance of music

by Jewish composers. In the very short article under his name it states,

‘He left nine symphonies which have been taken very seriously in Germany

and Holland but have never had much hearing elsewhere’. His 4th Symphony

was the first one we played, perhaps because being the shortest and

least complicated it was felt it would be the easiest one for the

audience to accept. Later we also played the 1st Symphony. It is now

difficult to understand the opposition there was to his music, not

only from the public but also from the musicians in the orchestras.

In many of his compositions Mahler

makes use of techniques that in the late 1940s and early 1950s were

resented by musicians in Britain and elsewhere. They resisted playing

in ways that they felt went against not only good taste but also against

some of the techniques they had practised so long and hard to perfect.

String players were instructed, at times, to glissando, slide

from one note to another. At its best this style can be heard in the

recordings made by the great violinists Fritz Kreisler and Jascha

Heifetz and other outstanding string instrument players in the first

part of the 20th century. The leaders of the many small light orchestras

playing in cafes, restaurants and holiday resorts were still playing

in this way in the 1940s. Increasingly, conservatoire trained musicians

had come to see this way of playing as vulgar and old fashioned and

to be avoided. Wind players were instructed by Mahler, at certain

points in the music, to raise their instruments so that they pointed

straightforward, rather than at an angle to the ground. Clarinettists

and oboists in particular were unhappy because it affected their embouchure

and to begin with many refused to follow this instruction. After the

mid-1960s, as performances of the Mahler symphonies became increasingly

popular, the complaints disappeared.

Charles Munch was another conductor

the LPO played under many times. He had immense charm (and the most

beautiful smile I’ve ever seen) as well as the ability to inspire.

Before he became a conductor he had been a fine violinist and was

the leader of the famous Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra when Wilhelm

Furtwangler was their conductor. He could on occasion be rather wayward.

I remember that when we were to play a Brahms symphony, that for some

reason it seemed he did not want to conduct, he barely rehearsed it

at all. But to play the French repertoire, Debussy, Ravel, Berlioz

and Rameau with him was really a great joy. In particular I remember

wonderful performances of Daphnis and Chloe, L’Apres Midi d’un

faune , La Valse and in particular La Mer. Years later

I remember playing it again with him with the Philharmonia in Vienna

in the wonderful Musikvereinsaal.

Someone, not really a conductor,

the orchestra always enjoyed playing with was Richard Tauber, generally

remembered as one of the great tenors of his time, equally at home

in the Mozart operas as in operettas and musicals. He proved, if proof

is needed, that formal lessons in conducting and conventional technique

are not required in order to obtain wonderful performances. Danny

Kaye, years later, displayed this same talent. Tauber brought a Viennese

charm to his Mozart and Schubert and an innate musical understanding

to everything he conducted. Unfortunately his vanity did not allow

him to wear glasses in public and this limited his repertoire as it

meant he had to conduct everything from memory.

Eduard van Beinum, then principal

conductor with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam, worked a

great deal with the LPO. A very fine musician, he was a restrained,

undemonstrative conductor who obtained very fine results in a wide

repertoire. He was greatly respected by the orchestra who really enjoyed

working with him. He was also a kind and remarkably tolerant man.

When we were recording The Songs of a Wayfarer by Mahler with

him in 1946 or 1947, our regular bass clarinettist was absent for

some reason and his replacement on that day was less than up to the

standard required. In one very quiet passage for the three clarinets

this player just could not play as softly as necessary. He was either

too loud, or came in too early, or did not come in at all. Finally,

after a number of unsuccessful attempts he became so nervous that

he produced the dreaded ‘squeak’. Rather than being cross and humiliating

the player in front of the whole orchestra, as many other conductors

might have done, he let it pass and left recording that section until

another day when another player had been engaged. It is a great pity

that he died before he had made as great an international reputation

as surely he would have done.

The Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet,

famous for his performances of the music of Stravinsky, was engaged

by Decca to record the music Stravinsky had composed for the ballet

Petrushka. Today this is accepted as a regular work in the

concert repertoire. In 1946 it was still a very exciting and difficult

composition for the orchestra. At that time we were still making records

in the 78rpm format. Each side of a record lasted about four minutes

without any facility for editing. If there was anything unsatisfactory

– a wrong note, poor intonation or ensemble, or a cracked note in

the brass, the whole side had to be recorded again. Decca allowed

10 three-hour sessions to record this 40-minute work, more sessions

than would normally be allocated for recording a piece of this length

even in 1946. But it was worthwhile; this recording, the first major

recording to make use of Decca’s new full frequency recording technique,

FFRR, was a great success and won an award. Years later I remember

recording Petrushka again with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra,

in the ‘long play’ 33rpm.format, when we were only allowed two sessions.

On that occasion quite a few of the musicians in the orchestra had

never played Petrushka before and so it required rather more

retakes than usual to splice the performance together to produce an

acceptable recording.

In 1946 when Leonard Bernstein came

to conduct the LPO he was still very young and full of New York ebullience

and chutzpah. He had recently had a great success with the

New York Philharmonic and did not seem to be at all impressed by the

LPO, no doubt finding it lacking in the kind of ‘attack’ he was used

to with American orchestras, and nothing like as virtuoso as the New

York Phil. For their part the orchestra did not like him because he

was young, brash and far too sure of himself. None the less, I recall

the performances were good, even if performed through gritted teeth.

He survived this brief encounter to become one of the most outstanding

conductors of his time and a remarkable many faceted musician: a virtuoso

pianist – his recording of the Ravel Piano Concerto in G major remains

one of the best still available – and a fine composer. As a composer

he is probably most widely remembered for West Side Story and

Candide. But his symphonies and much orchestral, choral and

chamber music still remain in the repertoire, though not performed

so frequently. Later, after a similarly false start to that he had

had with the LPO, he established a very good relationship with the

LSO. In time they came to like him very much and they did many splendid

concerts and recordings together. He was less successful when working

with the BBC Symphony Orchestra where on one occasion there was an

unfortunate confrontation between him and some of the brass section

on a ‘live’ TV broadcast.

The LPO engaged a number of conductors

who came to Britain for the first time in the early post-war years.

One of them, Sergiu Celibidache, at that time a very young man, made

a considerable impression and showed great promise. He had at one

time been a footballer and was still rather wild. Later he made a

considerable reputation as a conductor of great integrity, though

rather eccentric. He was one of the only conductors with an international

reputation who came to dislike commercial recording to such an extent

that after a few years he refused to do any further recording.

As well as Charles Munch two other

very good French conductors were engaged by the orchestra: Paul Paray,

and Jean Martinon. Like Munch they conducted a lot of French music,

a great joy to me – the repertoire is so dominated by the Austro-German

composers. The orchestra liked Paul Paray very much. He got very good,

exciting performances and we were sorry he did not return. He had

been a fighter in the French Résistance and was extremely tough.

On one occasion he refused come onto the platform at the beginning

of a concert until he received his fee – in cash! He was the Principal

Conductor of the Colonne Orchestra in Paris from 1945 until he went

to Detroit in 1952 where he had a very successful career with the

Detroit Symphony Orchestra before returning to Paris again in 1963.

Though he continued to conduct in France until his death in 1979 he

never returned to Britain. Jean Martinon was also admired by the orchestra.

He was a fine musician and a very good conductor and the orchestra

did a number of very good concerts with him. He had a considerable

success but, perhaps because of his easy personality and the fact

that when he first conducted us in 1945 he brought Ginette Neveu with

him, who was so charismatic and such a wonderful violinist, I remember

her more than him.

Three more conductors who had some

success with the orchestra were Albert Coates, Erich Leinsdorf and

Nicolai Malko. They could not have been more different from each other,

though each succeeded in getting good results. Albert Coates was already

elderly at the time and went out of his way to be pleasant to the

orchestra. He had made his reputation before the war in Britain and

also in Russia and by the time he conducted us was rather too easy

going and laid back to get outstanding results. In contrast Erich

Leinsdorf was fairly young, not particularly agreeable, but showed

that he had real ability. Many years later I took part in a number

of recording sessions with him when he conducted some extracts from

the Wagner operas with the LSO. By then he had established himself

as an outstanding concert and opera conductor. Though he was able

to get first class results he did not inspire orchestras sufficiently

to receive the accolade ‘great’. Nicolai Malko was a good conductor

of the old school; authoritarian, efficient but not inspiring.

|

|

Click

for larger picture

|

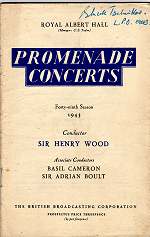

Of course we played frequently for

British conductors, most notably Sir Henry Wood, Sir Adrian Boult,

Dr Malcolm Sargent (still to be knighted) and John Barbirolli (again,

still to be knighted) and then, when he returned from the USA, Beecham.

Sir Henry will always be remembered for his part in creating the Promenade

Concert season, the ever-popular ‘Proms’. He was also the first truly

English conductor to make a great reputation. I only played for him

a few times after I joined the LPO in 1943 before the Prom season

that summer when the orchestra were to do all the

concerts in the first two weeks of the

season. I was looking forward to this

and the opportunity to play a large repertoire with him but, sadly,

he was taken ill and was able to conduct only the first two concerts

before he became too unwell to continue.

I don’t feel that Boult’s talents

were sufficiently recognised at the time by those who worked with

him. It is true that even those who played for him for many years

in the BBC Symphony Orchestra were often unable to tell what he was

doing with the very long baton that he favoured and though he could

be dull there was some music he did extremely well. I remember several

performances of the ‘Great’ C major Symphony by Schubert that were

very fine. The part he played in the formation of the BBC Symphony

Orchestra in 1930, his selection of the players that would make it,

at that time, the best orchestra in the country, and his subsequent

role in bringing a very great deal of new music to the public’s attention

was a very considerable achievement.

Sargent was unique in my experience

in that he was greatly admired by audiences and choruses, especially

by the ladies, and universally disliked, both as a man and a musician,

by orchestras. Only in the last years of his life, when he had somewhat

mellowed and his past was largely forgotten by a new, younger generation

of musicians, did orchestras come to have a better relationship with

him. His vanity and obvious contempt for orchestral musicians was

such that he would try to teach even the most distinguished and experienced

players how to play their part. His publicly expressed opinion that

a musician ‘ought to give of his life-blood with every bar he plays’

and that ‘the feeling of instability about where next year’s bread

and butter was to come from had made many an artist give continuously

of his best’, did nothing to create good feeling between him and the

orchestras. These remarks were particularly resented because in 1933

the orchestral musicians in London had made a substantial collection

for him when he was seriously ill. The great violinist Fritz Kreisler

said ‘I am sure that musicians the world over play better for feeling

secure. The more secure a musician feels the happier he is and the

better he plays’. Years later Sargent was involved in constant quarrels

with several leading principals in one of the orchestras. On at least

one occasion this led to him becoming so distraught that he started

to cry when outspoken criticisms about his ability were openly expressed

by some of the musicians in the orchestra. This did nothing to raise

his reputation as a man: orchestral musicians are only too accustomed

to very direct and sometimes wounding criticism.

The conductor that we admired the

most after Beecham was John Barbirolli, later Sir John, known by his

many admirers as ‘Glorious John’. In the LPO, when Beecham left to

form the RPO, the orchestra would have liked Barbirolli to have become

their Principal Conductor, but he had already taken up that position

with the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester when he returned to

Britain in 1943, after being with the New York Philharmonic, and was

not willing to leave Manchester. I also worked with him in the RPO

and the Philharmonia, always with pleasure. He did inspire both the

orchestra and the audience and must join the ‘great’ category. When

the Philharmonia toured South America in the 1960s Barbirolli conducted

most of the concerts. He created such enthusiasm from the audience

that on several occasions at the end of a concert, during tumultuous

applause, women bearing young infants would approach the stage apparently

seeking to have their children blessed by the Maestro. The

last time he conducted was at a rehearsal with the Philharmonia, in

preparation for a visit to Japan we were about to undertake in 1970.

During a rehearsal he suddenly became unwell and was unable to do

the tour. It was only a short while later that he died. His place

for the tour was very ably taken at extremely short notice by John

Pritchard (later Sir John), an extremely talented conductor.

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

(RPO)

The Royal Philharmonic was really

the only one of the four London orchestras to have a Musical Director,

Sir Thomas Beecham. It could be said, indeed it was, that it was his

orchestra. He not only conducted the orchestra a great deal he also

influenced the management of the orchestra in every way. In most British

orchestras the Principal Conductor usually does no more than about

12 concerts a year, a number of recordings and perhaps a tour. Quite

often, especially in the past when there was a great deal more recording,

the choice of a principal conductor was often determined by the number

of recording sessions he brought with him. The only other conductors

of a British orchestra that I can recall who performed a similar role

to Beecham were Sir John Barbirolli with the Hallé and Simon

Rattle (later Sir Simon) with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

Though Beecham gave me more pleasure

whilst I was playing in the orchestra than anyone else and has continued

to do so whenever I listen to the recordings he made, I can also recall

that at times he could behave very badly and very autocratically,

especially if one of his favourite players was not available. On one

occasion we were rehearsing with him in St. Pancras Town Hall when,

just before the tea break, the personnel manager came to announce

that an additional concert had been arranged several weeks hence.

The principal cello, Raymond Clarke, a magnificent player whom Beecham

admired and who greatly admired him in return, said, ‘I’m extremely

sorry Sir Thomas, I afraid I am not free on that date. I have already

accepted another engagement on that day’. Beecham went mad, shouting

and raving and being very rude and disagreeable to poor Clarke. He

worked himself into such a state that he came off the podium and went

storming through the orchestra, kicking chairs and music stands in

all directions, finally leaving the Hall and the rehearsal. With anyone

else the players would have found it difficult to forgive this kind

of behaviour. However, most of us recognised that at times he could

behave like a spoilt child, but forgave him because making music with

him was so rewarding.

When for some strange reason it had

been decided to present a series of concerts at the Earls Court ice

rink, Beecham displayed the autocratic side of his nature. A quite

low platform for the orchestra had been built on top of the ice. As

we waited for Sir Thomas to arrive for the first rehearsal, not surprisingly,

we found that we were getting very cold. Of course, as usual Tommy

was late. Someone must have told him about the prevailing conditions,

so that when he did arrive he came storming onto the ice, shouting

at the top of his voice, ‘I have been deceived – I have been deceived!

It’s a disgrace. Cancel the concert. Everyone go home.’ And with that

he went off again. It always seemed to me he walked with one leg in

2/4 and the other in 6/8 – I used to refer to him to my friends as

‘goody two-shoes’ – on this occasion it was a miracle he did not tumble

over on the slippery ice.

A few minutes later the personnel

manager came on to the stand and announced that the concert was cancelled

and that we could all leave. At about half-past four that afternoon

I received a telegram, as did all the members of the orchestra, instructing

us to return to Earls Court for a short rehearsal at six-thirty to

be followed by the concert at eight o’clock. It was quite remarkable

that everyone was still at home and able to respond to his call to

return. When we arrived back nothing had changed except that Beecham

now seemed to be in his normal good humour. The concert went quite

well, even though we were all frozen and it was very difficult to

keep one’s instrument up to pitch if one had more than a few bars

rest.

With Beecham conducting the orchestra

a great deal of the time the RPO did not have so many guest conductors

as the other orchestras in London. However, we did have some very

fine conductors, including Stokowski, about whom I wrote earlier.

We did a great deal of recording with Artur Rodzinski who was an excellent

conductor though he was not a pleasant man to work with; a martinet

and, possibly because at the time he was elderly and in poor health,

short-tempered and inclined to be rude. In 1956 when Gennadi Rozhdestvensky

came to London with the Bolshoi Ballet it seems that Beecham was impressed

by him because it was not long before he was engaged by the RPO. He

at once made a great impression on the orchestra. His conducting style

was absolutely idiosyncratic and his gestures, though frequently unconnected

to beating time in the generally accepted manner, were extremely effective.

I played with him in three orchestras, the RPO, LSO and the Philharmonia

and with all of them he obtained splendid performances. Subsequently

he was appointed Principal Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

This relationship was finally unsuccessful, largely because he disliked

rehearsing, a rare failing in a conductor. Though orchestras often

feel that conductors go on rehearsing far too long, Rozhdestvensky

would at times not rehearse a work that was unfamiliar to the orchestra

sufficiently for them to feel confident that they understood his very

unusual gestures.

Nonetheless, as I was to learn years

later, when he came to conduct the orchestra at the National Centre

for Orchestral Studies for me a number of times for concerts and broadcasts,

he could get the most remarkable performances from an inexperienced

young orchestra with the minimum of rehearsal time. On one occasion

I decided that we should create the tension of the recording studio

for the young musicians by asking Rozhdestvensky to record the suite

from the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin by Béla

Bartók. This is an extremely difficult piece for every section

of the orchestra, technically and rhythmically, so it was arranged

that there should be two extra rehearsals with another conductor before

Rozhdestvensky joined us. Rozhdestvensky was booked for two sessions,

10.00 a.m. until 1.00 p.m. in the morning and 2.00 p.m. until 5.00

p.m. in the afternoon. In the morning he arrived somewhat later than

ten o’clock, rehearsed for just over two hours and decided it was

time for lunch. As he wanted to get back home to central London (we

were working in Greenwich) he asked if we could restart at 1.30 instead

of 2.00. He rehearsed a few of the tricky places for about twenty

minutes and decided to record straight away. He recorded the whole

work without any re-takes or edits, said ‘ Thank you. Goodbye’ and

at about three o’clock went home. I have played this work a number

of times, with Rozhdestvensky and with other conductors, and always

found it difficult. Listening to this recording I find it hard to

believe it was done in one ‘take’, with so little preparation and

with young inexperienced players.

The Philharmonia Orchestra

When Walter Legge formed the Philharmonia

Orchestra in 1945, his position at EMI and the acclaim his new orchestra

quickly achieved enabled him to attract the most celebrated and sought

after conductors. Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler, George

Szell and Karl Böhm delighted the orchestra, audiences and critics

alike. Perhaps Legge’s greatest coup was to capture Herbert von Karajan

for the Philharmonia in the years before he replaced Furtwängler

as Principal Conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. I have

already written about Karajan, probably the most successful conductor

of the second half of the 20th century. At one time he dominated Europe

and had more power than any conductor before or since. His style was

to influence many younger conductors.

I was still in the RPO when Toscanini,

Furtwängler and Böhm conducted the Philharmonia, but I did

play for Karajan and always found it a rewarding experience. I also

played for George Szell. Though he was an outstanding musician and

conductor I did not enjoy the experience. I do not think it unfair

to say that most musicians around the world disliked him

Karajan conducted the Philharmonia

frequently before he took over the Berlin Philharmonic after Furtwangler

died in 1954. When I was still in the RPO the Philharmonia asked me

to do a concert with them in the Royal Albert Hall. This was the first

time I had played for Karajan and I remember how disconcerting it

was that he kept his eyes closed all the time. It was so different

from Beecham for whom the eyes were so important. He was a remarkable

conductor who combined nearly all the qualities required by a great

conductor. The wonderful sinuous musical line he obtained and the

subtle gradation of dynamic from the quietest pianissimo to the loudest,

powerful fortissimo was unsurpassed. A good example of this ability

can be heard in the fourth movement of Respighi’s The Pines of

Rome on the recording he made in 1958 with the Philharmonia. His

many recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic are evidence of the breadth

of his repertoire and his ability to create a truly magnificent virtuoso

orchestra.

I had the opportunity

of witnessing his astonishing gifts when we were in Vienna for several

days recording the Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. I

was delighted to be able to get a ticket for a performance

of Verdi’s Falstaff at the famous Vienna Opera House. My seat

was in a box that gave me a good view of the pit. It was a wonderful

cast: Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Giulietta Simionato, Tito Gobbi and with

Karajan conducting. After recording the Missa Solemnis during

the day Karajan came into the pit that evening and conducted, without

a score, an immaculate performance of this difficult opera. He demonstrated

some of the essential qualities a great conductor must have: a fantastic

memory, energy and stamina and a powerful musical intention with the

skill to convey that intention.

Another quality nearly all great conductors

share is their ability to conduct ‘light’ music, now seldom played

by symphony orchestras in the concert hall other than at the famous

Vienna Philharmonic’s ‘New Year’s Day’ concerts, or Johann Strauss

evenings that have become so popular. Barbirolli, Beecham, Charles

Munch and Karajan immediately come to mind. A

recording of The Skater’s Waltz by Waldteufel conducted by

Karajan with the Philharmonia is a very good example. In

the introduction to the waltz there is a lovely horn

solo.On this occasion it was played by Alan Civil, a fine artist in

his own right.. Like all great conductors Karajan lets Civil play expressively

and freely. The player feels he is playing just as he wants to, but

in fact it is within the context of the conductor’s conception.

Carlo Maria Giulini, extraordinarily

elegant and refined in both appearance and in his conducting, was

very fine in a wide-ranging repertoire, above all in his reading of

the Verdi Requiem. He did it a number of times in London with

the Philharmonia, each time better than the last, culminating in 1964

with what may well be the definitive performance of this wonderful

work. A video of that performance can be seen and heard at the Music

Preserved’s archives in its Listening Studio in the Barbican library,

within the Barbican Centre, and in the Jerwood Library of the Performing

Arts at Trinity College of Music. Though he was not actually a pupil

of de Sabata, he was much influenced by him and

shared some of his charisma and intensity.

Next

Page

Next

Page