Arthur

Benjamin:

Interview

between Richard Stoker and John France

Arthur

Benjamin

Richard,

can you tell me about your visit to

Arthur Benjamin.

Yes.

It was my very first visit to London.

I was still in my teens at the time

I had decided to make the 200 mile journey

from Castleford to the Capital to visit

the composer of the famous Jamaican

Rumba. My father gave me a lift

to Westgate Wakefield railway station

in the early morning. I was soon on

the train for the very first time to

Kings Cross. We lived almost half way

between Edinburgh and London.

Why

did you choose to contact Arthur Benjamin

and not to another composer living in

London?

Well

I had a wonderful teacher of composition

at Huddersfield called Winifred Smith,

who had been a former pupil of Sir Edward

Bairstow. She'd studied with him at

Durham. Winifred had taken me a long

way by 1957, and she knew I wanted desperately

to go to London to study further. She'd

taken me to Choral Society concerts

and to Leeds for the operas. Recently

we went to Manchester to the RVW concert

that included his new 8th Symphony.

One day she suggested sending some pieces

to Benjamin Britten, Arthur Benjamin

then Lennox Berkeley. Arthur replied

very quickly, so that's how he came

to invite me down. Of course Benjamin

was a high flyer by the mid fifties.

It is hard to imagine that he was right

up there in the first rank of composers

bearing in mind his subsequent undeserved

eclipse. So he was an excellent choice.

Also I knew of his success at the RCM

as a piano teacher, mainly of Ben Britten.

Arthur also received much publicity

in the Daily Mail- the paper we read

at home- and in magazines too. I'd also

heard how kind he was to composers starting

out.

For

the next year or so I had to stay in

Huddersfield and was unable to move

to the Capital. However, the composer

Harold Truscott arrived so I was lucky

enough to have over a year with him

too. It worked out really well for me

as I found out later. It was eerie to

find that Truscott knew many of the

musicians Lennox, Ben and Arthur had

worked with at the BBC in London.

Anyway

back to Arthur Benjamin- a fortnight

later a letter arrived- would I like

to visit him in London? I was delighted

to even receive a reply, so as a holiday

was coming up, I wrote back asking the

obvious question – ‘When?’

He suggested

a date and insisted I bring some of

my work. I was also invited for lunch.

It is strange how everything was arranged

by post in those days. Not the telephone

and of course email had not been invented!

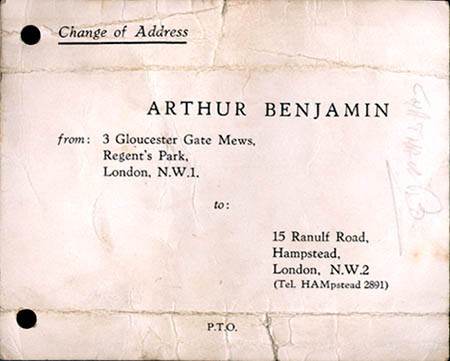

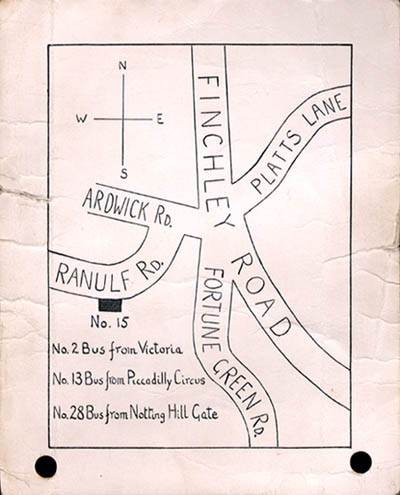

Just

before I headed south another letter

arrived asking me to bring everything

I had written with me. A map of Hampstead

was enclosed and the house where Benjamin

lived was clearly marked.

Can

you recall how you felt as you arrived

in the Smoke for the very first time?

Yes.

I remember what a thrilling experience

it was: the time in the three long,

smoky tunnels approaching King’s Cross

seemed interminable; then, as the train

came suddenly out into the sunlight,

the rhythm of the wheels seemed to spell

out the name Ar-thur Ben-ja-mn, Ar-thur

Ben-ja-min. The anticipation in the

last twenty minutes as the train approached

the station was overwhelming. At last

I stepped off the train onto the platform.

My first visit to London had begun.

Were

you planning to stay at Benjamin’s house

or with relatives?

No.

Neither. I had no-one to stay with in

London. I had made a postal booking

for a weeks stay at the YMCA in Tottenham

Court Road. I must admit that I liked

the atmosphere there. People from many

countries were staying there. And they

were from all kinds of backgrounds.

At first no one spoke to me. Most of

the men were lolling back in easy chairs,

reading their newspapers. Fortunately

for me there was a concert grand piano

in the large sitting room where I was

able to practice each morning. This

enabled me to get my compositions into

some kind of order. There were so many

of them!

Was

it all piano practise? Or were you able

to enjoy the big bad city?

I was

lucky to see Richard Burton as the First

Speaker in the stage version of Dylan

Thomas’ Under Milk Wood on one

of the nights in London.

I spent

a lot of time down the Kings Road at

a café called the Picasso. It

was here that I saw ‘Larry’ Olivier

walking down to the theatre. He had

begun the rehearsals for The Entertainer.

I met

up with some friends who were stationed

at the barracks in Chelsea and we went

to a number of films, including the

latest Peter Sellers.

How

did you feel about the city?

I was

excited by the prospect of visiting

theatres to see some plays, and my great

love at that time was the ballet. I

wanted to visit the art galleries, meet

people, sit sketching in London parks,

swim in the Serpentine!

Otherwise

I found London un-colourful and drab,

still recovering from the very recent

war years. All the men wore black, brown,

or mainly dark blue suits. Being a well

brought up Conservative boy, I kept

to the main streets, but strange elderly

looking women did come towards me from

the side streets of Soho - they hadn't

changed much since late Victorian times.

The police out on their beats suddenly

appeared close by, moving on luckless

unaccompanied girls of all ages who

were often simply looking in the shop

windows. There were bombsites about

and the rubble still piled up in places

even in 1957. Many places looked drab

but the weather and especially the sunshine

was a great change from the North.

Tell

me about the visit to Benjamin’s house.

The

big day finally arrived. It was 24th

July 1957…

I

was one and half years old then! Sorry…

…it

was a lovely sunny day. I noticed that

his address was ‘off Finchley Road’

– so I hopped onto a Number 2 bus. ‘Which

bit do you want?’ asked the conductor

gruffly, ‘This road goes to Edinburgh.’

I showed

him my map and he eventually put me

off in NW2.

Of course

I was nervous as I approached 15 Ranulf

Road. I noticed that it was a very smart

bungalow. As I reached the door with

my heavy case I felt more like a carpet

salesman than a composer.

I stood

nervously on the doorstep with my huge

suitcase crammed full of scores. I was

extremely jittery as I rang the doorbell.

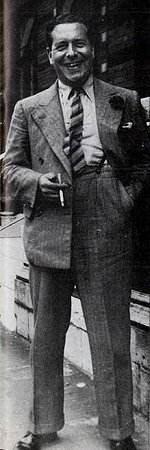

After a while Arthur Benjamin opened

the front door. He was quite jovial

and smiling. I remember he was dressed

in an open-necked royal blue summer

shirt worn outside his grey flannels.

And on his feet he had sandals with

no socks! Benjamin kindly helped me

to carry my heavy suitcase into his

hall.

He put

me at ease immediately. And in moment

I was invited into his music room at

the back of the house. I particularly

recall as I passed thought the hallway

that I could hear someone preparing

a meal in the kitchen – his wife, perhaps?

Can

you tell me about his music room?

It was

large. There was a French window leading

out onto the garden. To the right of

this was an alcove with a bow shaped

window; here was a window seat and a

large table with glossy magazines laid

out on it. They were not musical. And

there was the latest Eric Ambler novel,

which was lying face down on the table

as if it had just been put to one side.

It

must have been quite daunting for a

nineteen year old lad to be sitting

in a famous composer’s study. Did he

make you feel welcome?

Yes.

His first question was, ‘Sherry? Would

you like a drink?’ I thanked him. ‘I’m

having a brandy – doctor’s orders. You

see, I have a weak heart and my doctor

says that one brandy each morning will

do me good. That suits me fine!’ he

laughed.

I

imagine that he must have been a bit

concerned at the great suitcase you

had lugged all the way from Tottenham

Court Road.

Well

no actually. He did not seem in the

least bit surprised at it. All he said

was, ‘Those must be your scores,’ he

said pointing at the case. ‘ It’s best

if I see all that you have written –

for the simple reason that you might

leave your best efforts at home and

bring me your less inspired ones.’

I

understand that the evening before Benjamin

had heard the world premiere of his

opera A Tale of Two Cities at Sadler’s

Wells. Did he talk about this?

He made

an apology about being ‘unusually elated.’

But of course I had noted that he was

more than just plain cheerful. He told

me how the opera had been a great success

and how he had seven curtain calls.

The work had been broadcast three years

earlier but this was the stage premier.

The main protagonist had been superbly

established by Heddle Nash and the young

soprano Heather Harper had performed

wonderfully. I later found out that

the work had won a Festival of Britain

award in 1951.

I

must confess, Richard, that I have never

really associated Arthur Benjamin with

opera.

Well,

opera was in fact Benjamin’s favourite

medium. He told me that he was hoping

to compose another one soon, based on

Moliere’s play Tartuffe. This

was to be written to a libretto by his

close friend Cedric Cliffe.

I remember

that he then talked to me about Giacomo

Puccini. ‘There is someone who knows

how to write for the stage. He saw the

play first, and if they worked dramatically

he turned them into the most beautiful

and successful operas…and what orchestration!

Many of our own composers forget the

stage when they write operas….un-dramatic

works they are!’

Did

he not have much time for the operas

being written in England at that time?

I mean what about Britten.

I said

to him – ‘But what about Peter Grimes?’

He had a lot to say about this. ‘Oh

yes...that is a masterpiece. I was thinking

more of our older composers. VW (Vaughan

Williams) is my idea of the great professional

in music. I admire him above all other

living composers, but unfortunately

his operas are not dramatic enough.’

Arthur

Benjamin lamented to me that this was

such a pity. He insisted that VW was

still a great man and a perfect example

to all of us of professionalism.

It was

a leitmotiv of our conversation. ‘Be

professional, my boy, be professional.’

Of course

this is what Arthur Benjamin was himself

– a true professional.

Did

he admire Benjamin Britten?

Yes

he did- but with qualifications. He

insisted that he thought BB enormously

talented. But he was of the opinion

that he had too much success too early.

And Benjamin felt it had gone to his

head! He said to me – ‘It is what you

are like at 50 that counts in the serious

music world.’

Of course

at that time the age of 50 seemed an

eternity away to me.

Arthur

disliked the way Ben had treated people

and how he'd failed to listen to what

he (Arthur) considered as good advice.

Britten found criticism difficult to

take.

Arthur

Benjamin felt that Britten’s opinion

of his composition teacher John Ireland

was unfair both as teacher and as a

man. However, he thought that it was

unfortunate that the young Britten had

been given John Ireland as a composition

teacher after having studied privately

with Frank Bridge. Benjamin found Ireland

often a good teacher, but the outstanding

qualities of the practical Bridge was

'a hard act to follow, yet when at his

best Ireland was a highly inspired composer.

He felt

that Britten had ‘gone down’ since Peter

Grimes. Of course at that time the

War Requiem had not been written.

I wonder if Arthur Benjamin would have

changed his opinion?

But

was Arthur Benjamin indifferent to the

achievement of The Turn of the Screw?

Yes,

he did admit that this work was an exception.

In fact I believe he thought it was

a very good piece and he admired the

subtle and effective use of the chamber

orchestra.

I

know that Benjamin taught BB piano at

the Royal College and the attractive

Holiday diary was dedicated to him by

his pupil – did he mention this?

Well

he did not actually mention this but

he did insist the Britten was an exceptionally

good pianist. Of course Arthur also

taught Helen Perkin.

That

was the student to whom John Ireland

dedicated his Piano Concerto?

Yes,

apparently Ireland had been walking

past one of the practice rooms and had

heard her playing during a lesson with

Benjamin. This inspired him to write

the concerto!

Did

he say anything more about Britten?

Arthur

said that Ben, whom I was to meet for

the first time six months later, had

got into entirely the 'wrong set' after

leaving the RCM. 'You mean musically?'

I asked.

'No',

he said 'the Oxbridge group of writers.

It's made him too political and turned

his head a lot.' You see Ben had been

extremely lucky in his teacher Frank

Bridge, he went to him at exactly the

right age, Bridge was remarkable, he'd

also taught Howard Ferguson, and then

when Ben came under the spell of the

Oxbridge group, Bridge was furious.

You see, according to Arthur, Ben was

over-ambitious, wouldn't take his time

... he found it hard to take criticism.

Vaughan Williams disliked the 30's Oxbridge

people too, I'm sure he shared Arthur's

views, (later at the flat of the then

RAM Principal Sir Thomas Armstrong I

happened to say as he poked at his fire,

that, " The thirties poets are remarkable."

Sir Tom turned round brandishing the

poker: "Young upstarts the lot of them!".)

Benjamin,

Armstrong and VW had all fought in the

First World War, so the way many of

the ‘thirties’ young men acted over

the Second World War had a lot to do

with their attitude.

Arthur

maintained that Bridge besides being

a great teacher was a first-rate composer,

but that Ben had difficulty knowing

who to listen to. At that time he was

still very young, almost a ‘Peter Pan’

like figure who needed advice and protection.

It appeared

to me that it was Britten the man, rather

than Britten the composer, that he had

doubts about. 'He has so many of the

"Right" people about him, they do everything

they can for him, to give him "space"

in which to compose, but I often worry

about what it is that motivates him,

he seems to have so many hang-ups, psychologically

he's had a hard life so far. You see

he showed me all his early scores and

I still try to keep up with his many

Premiers.

Arthur

thought that Ben would burn himself

out at the rate he was composing after

'Grimes'. He agreed though that Ben

was one of the greatest talents to emerge

since Elgar.

Yet

Arthur confessed that preferred the

deeper, more solid works, of his piano

pupil the composer the late Bill (William)

Blezard.

Incidentally

Blezard once told me that Arthur couldn't

stand Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony

when he heard it played, or it was mentioned

to him, he'd shouted out

'Bloody

Cuckoos!' which he'd often said with

some vehemence.

So I

suppose it came as no surprise to hear

Arthur say he hadn't liked Ben Britten’s

Spring Symphony for similar reasons.

I told him that the 'Spring'

was a favourite of mine, that I liked

in particular the opening chorus and

the Auden setting.

It

would not surprise me if you quizzed

Arthur Benjamin about Lennox Berkeley

either?

I did

and he said, "Ah, he's my type of composer,

a true professional, he takes his craft

seriously. He was extremely well taught

in Paris by Nadia Boulanger.’ He then

told me how well Lennox writes for the

stage. In fact, it had been only nine

months since his really excellent one

act opera Ruth had been staged,

Benjamin felt that it was a remarkable

achievement for a long ‘one-acter’,

He was impressed by Berkeley’s ability

to write the ‘Mozart type’ of composition

with his captivating comic opera A

Dinner Engagement. However Benjamin

felt that Lennox’s real masterpiece

was his large scale three act opera

Nelson. This was written to a

libretto by Alan Price Jones.

Arthur

sipped his last drop of brandy and filled

my glass again.

I

am interested to hear you mention William

Blezard. I actually think his music

is extremely attractive. I remember

a friend pointing him out to me once

in Barnes – where he lived.

Yes

– well Benjamin told me that Blezard,

who had toured as pianist with Marlene

Dietrich, Joyce Grenfell, and more recently

Honor Blackman, had been told by Arthur

that he'd given a title to a composition

for a printed programme, and then wrote

it in time for the concert.

Bill

had once or twice bumped into Arthur

later at the Denham film studios recording

his own feature film scores with conductor

Muir Mathieson (1947-49).

What

other pupils did Benjamin teach - either

at the time of your visit or later?

He taught

Ivan Clayton, Joan and Valerie Trimble,

Irene Kohler, Lance Dosser, Bill Blezard

told me that Herbert Howells taught

in the room almost opposite Arthur and

if Arthur liked a composition he'd fetch

Howells in to hear it. So, like Nadia

Boulanger he'd enjoyed looking through

his piano pupil's compositions at the

RCM.

Perhaps

the composers were given to Arthur to

teach them piano then they would obtain

second opinions of their works. Arthur

had been a child prodigy giving his

first piano recital aged six. In1931

he'd given the premiere as soloist of

Constant Lambert's Piano Concerto with

Lambert conducting.

Did

Benjamin give his views on any other

contemporary composers during your visit?

Arthur

was greatly impressed by Peter Racine

Fricker too. His very close friend was

Gian Carlo Menotti who often kept in

touch with him as did many of the younger

American, New Zealand and Australian

composers most of whom were published

in this country. 'I love Menotti's Consul,

The Medium, The Telephone

and Amahl too ". He also said

that some of the younger generation

were, 'losing their way stylistically',

feeling that Ben was 'in danger of trying

to follow them'.

Composers

like Lennox Berkeley, Walton, and Francis

Poulenc, whose Carmelites had

recently been premiered, were going

along on more productive traditional

lines, yet still producing something

personal and individual.

He said,

his eyes lighting up, all composers

should model themselves on Mozart, as

I try to do, it means attempting to

compose music on a number of levels,

with communication as the main goal,

very hard to do this but that Lennox

Berkeley and the younger Peter Fricker

were managing and Ben certainly had

done in his early works which had 'astounded

us all'. Arthur Benjamin had composed

an opera for Television, the first ever

commissioned by the BBC.

It

is perhaps not widely realised that

Arthur Benjamin was an exceptionally

accomplished pianist in his own right.

Did he talk about his solo career? I

know that he gave the first European

performance of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in

Blue.

Well

yes he did. Actually after chatting

about Ireland and Britten he went quite

sad. Just as if a cloud had come over

his smiling face. He told me how he

wished he had concentrated on composition

alone. He felt that somehow he had spoiled

his chances by being a teacher and a

concert pianist, a conductor, a light

music composer and arranger and a film

composer. He reckoned that you are not

taken seriously if you are a jack of

all trades.

He said

to me – "Specialise…specialise

in composition my boy, and be tremendously

patient…wait to be asked to compose,

do not thrust your music at people –

put ‘em off and it’s very unprofessional.

Wait to be asked…it’s much better that

way. The music’s valued then if it has

been commissioned."

Then

he cheered up and suggested we had lunch.

One

thing is interesting me – you mentioned

noises off in the kitchen. Was this

his wife? Were you introduced?

Well,

it’s quite interesting really. When

he said ‘Let’s have lunch’ he knocked

on the door of a serving hatch at the

back of the room. It opened immediately,

to reveal a Jamaican manservant. Benjamin

introduced us through the hatch, and

we shook hands. I had never shaken hands

through a serving hatch before!

Benjamin

revealed to me cooking was one of his

hobbies and that he had cooked the meal.

The manservant was serving it and bringing

it through.

We sat

at a dining table in the centre of the

room. The Jamaican came through form

the kitchen, a huge dinner plate in

each hand.

‘Steak

– I hope you like steak,’ Benjamin said.

‘I shopped for it this morning. I asked

the butcher for two portions, and he

has given me two navvies!’ I remember

that the streaks absolutely filled the

plates – there was hardly any room for

the vegetables and salad.

Benjamin

insisted that we did not talk about

music whilst we ate. He said that it

can spoil the digestive process. ‘Tell

me about yourself- and then after lunch

we can go through your composition.’

Actually

this made me feel very grand – he took

me and my musical efforts so seriously.

I tried

to eat the huge meal, telling Benjamin

about my early life and studies without

mentioning music. This was difficult,

and I finished the meal last. He then

invited his manservant to join us for

coffee. Benjamin’s manservant said very

little, but I remember he looked very

much like the great, legendary cricketer,

Viv Richards!

So

did you eventually get to discuss your

compositions?

Yes.

Benjamin asked his manservant to leave

us so that we could go through Mr Stoker’s

compositions. He indicated the dishes,

saying – ‘Leave the things – we can

clear away later.’

Then

I noticed a very large draughtsman’s

table at least eight feet by seven,

on a large steel frame. I learned that

the composer stood at this to work on

his orchestration, the light coming

in from behind him through the open

French windows. I also noticed the large

garden and told him how lovely it looked.

‘Yes

it is so private out there, I can sunbathe

naked. No-one can see through the privet

hedges and trees. There cannot be many

places so near London where you can

do that!’ he said proudly.

We sat

down at his grand piano – a Bechstein,

and started going thorough my pieces,

playing them as piano duets, with Benjamin

pedalling. He was very encouraging,

often saying, ‘Yes, I like that!’ Then

we approached a climax. ‘No,’ he said,

‘you must REACH your climaxes…they seem

to fall away. Have as many as you like,

but you must reach each one in the end

– then the listeners will not be left

unsatisfied. Listen to Ravel!’

Obviously

he was sight reading my works and I

was impressed at how competent he was

at this. He seemed to understand the

character of my piece immediately. His

playing of my works was quite thrilling

and extremely musical.

He looked

through some of my other pieces without

playing them, telling me which he liked

best. ‘This will help your taste to

develop, if I point to the good things

and leave the weaker ones.’

Then

he said to me – ‘I am not a composition

teacher. You cannot teach it – you can

only guide a young composer. I’ve never

taught composition. I’m willing to give

advice to you, but not to teach. A very

talented Welsh composer keeps saying

in his brochure and programme notes

that he studied with me- well, he didn’t.

I just gave him advice, as I have done

to one or two others. I hope you will

never say that you studied with me,’

he stressed. ‘You can say I gave you

advice…I’d like that very much better.’

I

know that Benjamin himself studied at

the Royal College of Music with Parry.

Did he mention this to you?

He actually

studied with both Parry and Stanford.

He claimed that both were very great

teachers. However he had some hard things

to say about the RCM. ‘That place has

gone down and down,’ he said somewhat

wistfully. ‘I resigned with one or two

other professors. It’s their Registrar,

Anson. He’s been no good for the place.

He’s so bad that he drives people away.

The Director Bullock is not much better.

He’s easily led…under Anson’s thumb.

No! Do not go to the College – Go to

the Academy. They’ve just got a new

Principal who is very good. He likes

composers and he will look after you

there. He’s called Thomas Armstrong.

I was in there a few days ago examining

their Piano Division Five and the Recital

Diploma. Armstrong has turned the Academy

very quickly into a good place to study…more

like the Royal College was when I studied

there. ‘

Were

you disappointed that Arthur Benjamin

would not take you on as a pupil?

Well

yes, of course. But I asked him who

would be best for me. He suggested Matyas

Seiber and Lennox Berkeley. He considered

them to be the best teachers of the

day. They had taught Peter Racine Fricker

and Richard Rodney Bennett.

Suddenly

Benjamin took me over to a sideboard

in the corner of the room. ‘Would you

like to see my proudest possession?’

I nodded, following him. He took down

a small black-framed photograph, covering

up some writing at the bottom. Showing

to me he asked if I knew who it was.

I looked

at it for a moment. ‘It’s Brahms isn’t

it?’ I replied.

Yes…and

look, he’s signed it.’ Sure enough,

the clear signature of Johannes Brahms

was written along the bottom of the

photograph.

Benjamin

told me that Brahms had always been

his favourite composer. Benjamin had

been only four years old when the elder

man had died in 1897.

He continued

for a while about Brahms. ‘I had to

keep my love of him secret from my Royal

College colleagues, though…Brahms was

out of favour in the nineteen twenties

and thirties. It was the gypsy element

they couldn’t take...too light and popular

for them, you see.’

Benjamin

then talked to me about Mozart. ‘What

a model! To write a piece of music that

can be appreciated on so many levels

and so light in texture. Not a note

too much. This should be the aim of

all composers.

Did

he talk about his own music to you?

Benjamin

loved Ravel’s music too. He told me

that he had just composed a suite for

Gervase (de Payer), the brilliant clarinettist.

He had called it Le Tombeau de Ravel,

after Ravel’s title, Le Tombeau de

Couperin. He insisted that Boosey

& Hawkes would publish it. He mentioned

that he had done a version for viola

and piano – just as Brahms had done

with his two clarinet sonatas.

Of course

he was a versatile composer – writing

in many idioms. Not only did he produce

a fine symphony, four operas, concertos

and piano music, but also film music.

He told me that he had written a cantata

for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who

Knew Too Much. Apparently this contains

a shot of the composer himself, seated

at the end of a row in the audience

at the Royal Albert Hall.

I could

see how excited he was about his future

plans

What

are your final thoughts about Arthur

Benjamin?

Well

this was only the first of many visits

that I made to him. On another occasion

he had been badly stung on the face

by a wasp whilst sunbathing (lucky it

was his face as he had a predilection

for doing it nude! Ed.) He was not,

unsurprisingly in quite so good a mood.

Another time he wrote to me to cancel

a visit – ‘I am off on a banana boat

to the West Indies to find some sun.’

You know, the Jamaicans gave him a barrel

of rum each year for making their island

so popular with the Jamaican Rumba

– and he was always welcome there.

Then

in 1960 I heard of his sudden death

on 10th April. This was only

a few days after his three-act opera

A Tale of Two Cities had received

its American premiere at the State College,

San Francisco on the 2nd

April. Some four years later his Moliere

opera Tartuffe was successfully

produced at Sadler’s Wells.

What

do you feel about his position as a

composer in 2004?

Well

after his death his compositions have

been mostly neglected and I believe

a general re-assessment of his works

is long overdue. Obviously he is best

remembered for his Jamaican Rumba

which was composed in 1938. However

there is a fine recording of the Symphony

No.1 and the Ballade for String

Orchestra on Marco Polo (8.223764)

and a number of chamber works and piano

pieces are also available. A biography

is also in the process of being written

by the Australian pianist and scholar

Wendy Hiscocks.

Richard

Stoker/ John France April 2004