Two contemporary composers of the older generation, likely to be daunting for some listeners, were featured in the Proms, together with classics by two radical innovators of earlier times, Stravinsky and Varese.

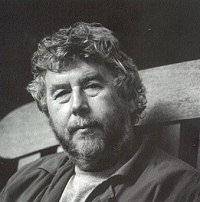

Sir Harrison (Harry) Birtwistle is now recognised as the leading British composer since Tippett's death, but he also remains the bête-noir for people who don't like modern music and are repelled by its often-harsh tone and abrasive dis-harmony.

Interviewed the

evening after the London premiere of Harrison's Clocks (1998) he explained

disarmingly that he had no particular compositional credo nor axe to grind,

"I just do what I do". He writes as he finds natural, and it never occurred

to him to compromise to please audiences. Off-putting in responding to a

long-winded interlocutor - "so, what's the question?" (Birtwistle should

be an ideal interviewee at examinations for prospective interviewers!) He

also became spontaneously expansive, checked only by time constraints.

Interviewed the

evening after the London premiere of Harrison's Clocks (1998) he explained

disarmingly that he had no particular compositional credo nor axe to grind,

"I just do what I do". He writes as he finds natural, and it never occurred

to him to compromise to please audiences. Off-putting in responding to a

long-winded interlocutor - "so, what's the question?" (Birtwistle should

be an ideal interviewee at examinations for prospective interviewers!) He

also became spontaneously expansive, checked only by time constraints.

He was at the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens to introduce

three of his chamber pieces for winds, played by the excellent young

Galliard Ensemble, formerly students at the Royal Academy of Music

in London and 1999 PLG Young Artists. And indeed he conducted, or as he said

"beat time", to assist negotiation of the tricky Hoquetus Petrus (after

Machaut) for the bizarre and impracticable combination of two flutes with

piccolo trumpet (Mark Law).

He was at the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens to introduce

three of his chamber pieces for winds, played by the excellent young

Galliard Ensemble, formerly students at the Royal Academy of Music

in London and 1999 PLG Young Artists. And indeed he conducted, or as he said

"beat time", to assist negotiation of the tricky Hoquetus Petrus (after

Machaut) for the bizarre and impracticable combination of two flutes with

piccolo trumpet (Mark Law).

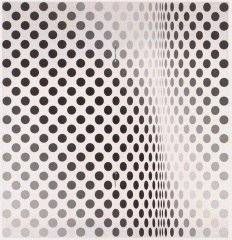

The Serpentine Gallery is an attractive, modern space, showing now a stunning retrospective exhibition by the op-artist Brigid Reilly. Music and pictures counterpointed each other in striking interaction, the one playing disturbing tricks upon the eyes, the other producing aural near-pain in the central gallery, its reflective walls and domed ceiling tending to exaggerate the difference tones produced by flutes and oboe in high registers. A difficult acoustic, in which lutes or a few strings would sound good (cp. another new concert venue, the South London Art Gallery, featured in S&H August, a real discovery).

Kathryn Thomas and Anne Elkjar Hansen played the more accessible Duets for Storab, and the core Galliard Quintet (Kathryn Thomas, Owen Dennis, Katherine Spencer, Helen Simmons and Richard Bayliss) ended with the most substantial and satisfying of the three works chosen, Five Distances, for horn at the centre, flanked by flute and bassoon to the left, clarinet and oboe on the other side.

Birtwistle was encouraged naturally to talk too about his important new work for solo piano, its title alluding both to his own name and to the justly famed John Harrison who developed the first reliable navigational chronometers in Greenwich (celebrated in Dava Sobel's book Longitude, essential Millennium reading!).

These substantial pieces (duration about 25 minutes) continue Birtwistle's preoccupations with time and musical mechanisms. He explained that being a non-pianist, quite unable to play his music up to speed; he was freed from the constraints of pianistic finger patterns to which virtuoso composer-pianists readily resort to ensure effectiveness in performance. Tippett, who improvised wildly in private whilst composing at the piano, was another who depended upon professional pianists to realise his innovations for the instrument. Ligeti's studies, enormously complex yet already standard repertoire for younger pianists, have a similar originality, and come to mind when listening to the five Harrison's Clocks, challenging, exhilarating and fiercely individualistic music, acclaimed by the Proms audience. They too are sure to be tackled by pianists of the new generation in due course.

Harrison's

Clocks is an important and very welcome addition to Birtwistle's oeuvre,

valuable for studying at home to get closer to the composer's musical thinking,

even for amateur pianists of limited ability. (What a tragedy that Benjamin

Britten, a wonderful pianist, never produced a substantial solo piano work

for home pianists to study!)

Harrison's

Clocks is an important and very welcome addition to Birtwistle's oeuvre,

valuable for studying at home to get closer to the composer's musical thinking,

even for amateur pianists of limited ability. (What a tragedy that Benjamin

Britten, a wonderful pianist, never produced a substantial solo piano work

for home pianists to study!)

A CD of the complete set is promised soon by Sound Circus; meanwhile Joanna MacGregor rehearses Harrison's Clocks with the composer and performs Clock 3 on her autobiographical compilation CD Outside in Pianist, SC 002.

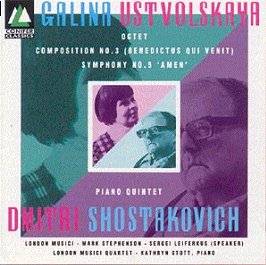

Galina Ustvolskaya's name has become better known during this her 80th year, and we are even beginning to learn how to pronounce it! However, only now have performances of her music begun to reach larger audiences and the Octet, given by Lontano conducted by Odaline de la Martinez at the Proms, and broadcast simultaneously, was a landmark in her growing recognition.

Ustvolskaya lives quietly in St Petersburg, shy and reclusive. She is to be featured in November at this year's Huddersfield International Festival of Contemporary Music, which S&H will be covering despite there being no expectation that she might attend personally. Ustvolskaya in her youth became a pupil of Shostakovich, who predicted her worldwide renown. Later his friend and respected younger colleague, Shostakovich quoted from her compositions in his own and averred that it was she who had influenced him; it is said that she turned down his marriage proposal! As with the equally unconventional mid 20th century Italian avant-gardist Giacinto Scelsi (who vowed that anyone who photographed him would not leave alive!) there have until very recently been few pictures of Ustvolskaya, the most familiar worn and decades old.

Only

since the break up of the Soviet Union has Ustvolskaya become well known

as a composer of ferocious integrity and complete individuality, her music

direct yet original, and instantly recognisable as unlike anyone else's.

She does not use bar lines and combines asymmetrical polyphonic combinations

with powerful rhythmic drive. She stands outside fashion, past or present,

hallmarks of her style being unswerving severity and seriousness, presented

in a predominantly harsh, hard-edged sound spectrum. It is bleak, compelling

music, bravely epitomising the rigours of life in Soviet Russia and the

suppression of artistic freedom in the Stalinist era. Ustvolskaya's music

is devoid of 'feminine' traits and she believes that separate concerts for

women composers humiliate the music. She prefers her music to be played in

large spaces so the Albert Hall was perfectly suitable for the Octet (1950)

even though the instruments are few. She favours small, unusual combinations,

in this case four violins, two oboes, piano and timpani. It is ritualistic

with motives locked into rigid yet frequently shifting rhythmic patterns,

with constantly changing time signatures. There are three well contrasted

movements, the last culminating with a battery of apocalyptic timpani strokes,

almost suggesting a firing squad, according to the liner notes for Conifer

Classics CD 75605 51194 2, which includes also her Composition No 3 for

four flutes, four bassoons and piano, and the Symphony No 5 for reciter,

violin, oboe, trumpet, tuba and percussion, these appropriately coupled with

Shostakovich's Piano Quintet.; recommended.

Only

since the break up of the Soviet Union has Ustvolskaya become well known

as a composer of ferocious integrity and complete individuality, her music

direct yet original, and instantly recognisable as unlike anyone else's.

She does not use bar lines and combines asymmetrical polyphonic combinations

with powerful rhythmic drive. She stands outside fashion, past or present,

hallmarks of her style being unswerving severity and seriousness, presented

in a predominantly harsh, hard-edged sound spectrum. It is bleak, compelling

music, bravely epitomising the rigours of life in Soviet Russia and the

suppression of artistic freedom in the Stalinist era. Ustvolskaya's music

is devoid of 'feminine' traits and she believes that separate concerts for

women composers humiliate the music. She prefers her music to be played in

large spaces so the Albert Hall was perfectly suitable for the Octet (1950)

even though the instruments are few. She favours small, unusual combinations,

in this case four violins, two oboes, piano and timpani. It is ritualistic

with motives locked into rigid yet frequently shifting rhythmic patterns,

with constantly changing time signatures. There are three well contrasted

movements, the last culminating with a battery of apocalyptic timpani strokes,

almost suggesting a firing squad, according to the liner notes for Conifer

Classics CD 75605 51194 2, which includes also her Composition No 3 for

four flutes, four bassoons and piano, and the Symphony No 5 for reciter,

violin, oboe, trumpet, tuba and percussion, these appropriately coupled with

Shostakovich's Piano Quintet.; recommended.

Much of Ustvolskaya's extensive catalogue of solo piano music is not too hard for amateur pianists to tackle. Try the Eleven Preludes. [PGW has an extensive article about Ustvolskaya's piano music in Gramophone's current IPQ (International Piano Quarterly) Summer 1999] Her piano music is all available from Boosey & Hawkes, as is too is Birtwistle's Harrison's Clocks

(£14.50p from http://www.boosey.com/musicshop/acatalog).

Peter Grahame Woolf

Seen&Heard is part of Music on the Web(UK) Webmaster: Len Mullenger Len@musicweb.force9.co.uk

Return to: Seen&Heard Index

Return to:

Music on the Web

Return to:

Music on the Web