Other Links

Editorial Board

-

Editor - Bill Kenny

-

Deputy Editor - Bob Briggs

Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN AND HEARD

UK OPERA REVIEW

Wagner, Lohengrin (new production):

Soloists, Staatsopernchor Berlin, Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim

(conductor). Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, 8.4.2009 (MB)

Cast:

King Henry the Fowler – Kwangchul Youn

Lohengrin – Klaus Florian Vogt

Elsa von Brabant – Dorothea Röschmann

Friedrich von Telramund – Gerd Grochowski

Ortrud – Michaela Schuster

The King’s Herald – Arttu Kataja

Production:

Stefan Herheim (director)

Heike Scheele (designs)

Gesine Völlm (costumes)

Olaf Freese (lighting)

fettFilm (video)

Throughout, the exterior manifestations of theatrical craft remind us of the

instrumentalisation at work. And at the end, we see Wagner’s own words, always

disregarded by his would-be protectors – remember, Protector is also the title

awarded by the king to Lohengrin in

At the heart, yet curiously and rightly decentred, was Klaus Florian Vogt’s

Lohengrin. This was a straightforwardly outstanding performance, following in

the footsteps – at least in my listening experience – of his

Erik and his

Walther. Strength and beauty of tone are brought together in a marriage of

heroic and lyric tenor. Has Vogt made a pact with the Devil? Might we at last

have found a Siegfried? Moreover, there was something quite terrifying about the

emptiness of his stage delivery, which, when married to such seductive means,

brought us closer than many would doubtless have liked, to a profoundly serious

confrontation both with ourselves and with our historical demons. Elsa was

powerfully portrayed by Dorothea Röschmann, occasionally a little strained, but

more usually with a tender, word-attentive lyricism. Her nobility was all the

more moving – and credible – for being tarnished by her brush with charismatic

power. Telramund and Ortrud, whilst far from being vindicated, are transformed

by the production into rather more complex figures than often they will appear.

In terms of performance, Gerd Grochowski was a Gunther-like figure, believable

in his weakness but perhaps a little lacking in strength as a real alternative

to Lohengrin. Michaela Schuster, on the other hand, was superb as an Ortrud

driven mad or madder by the unfolding events, events which chillingly excluded

her as an outsider. Her unhinged malevolence made no excuses but, as she spat

her contempt, we at least began to question why. As a force of ‘traditional’

normality, Kwangchoul Youn provided a firm, noble foundation as King Henry,

though we all know how swiftly charisma can sweep away traditional legitimacy;

the uncertainty of his rule of law was terrifyingly apparent. And the Herald’s

transformation from

Staatsopernchor Berlin (chorus master: Eberhard Friedrich)

Staatskapelle Berlin

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

The Prelude to Act One, performed with magnificent luminosity by the

Staatskapelle Berlin, depicts Richard Wagner both as puppet and puppeteer, an

ambiguity to be revisited upon many of the characters. Apparently assumed into

heaven, a similar fate – albeit with an all-important distinction – will be

visited upon Lohengrin at the work’s conclusion. Wagner’s presence is seen on

stage throughout the work, sometimes in multiple guises, whether as puppets or

as chorus members – frockcoat, altdeutsch cap and all – and sometimes

melding with other members of the depicted Volk, both changing them and

being changed by them. Herheim’s treatment of the chorus is thought-provoking

throughout, taking advantage of what can in lesser hands seem like rather stock

responses to present a Volk dangerously swayed by the ministrations of a

charismatic leader and dangerous through its responses thereto. Losing their

individuality, as illustrated by their loss of individual modern dress, and

subsumed into a bland yet fearsome force of social repression, rejoicing in an

impossible, Magritte-styled Eden, followed by a make-believe world of horned

helmets and other neo-mediævalisms. The German catastrophe is unmistakeably

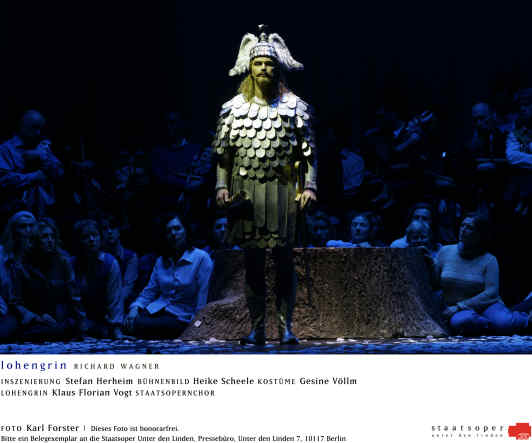

present. Heike Scheele’s Brabantian sets and Gesine Völlm’s costumes are here a

splendid riposte to those who actually claim to wish to see the vacuously

‘traditional’, which is of course nothing of the sort. For Lohengrin, when he

arrives, apparently straight from Neuschwanstein, is the menacingly kitsch

instrument of transformation from an opera house in modernto a world of fantasy. Gleichschaltung is the name of the game, as it was

once before under a seductive leader with nothing but emptiness for a core. We

can read what we want into him and that is part of the problem. Like his

creator, he will be assumed upwards but then, to seal the tragedy, will come

crashing back down to earth.

I mentioned Herheim’s virtuoso direction of the Volk-chorus. This would

have amounted to little, had it not been for a superb performance from its

members, very much back on form, as they had been in the

previous night’s Ein deutsches Requiem. The Staatskapelle Berlin was

on equally excellent form, this music playing to its ‘old German’ strengths,

although Herheim’s production of course rightly problematises the very concept

and reminds us of the orchestra’s modernity, including its fine record under

Daniel Barenboim and others in contemporary music. Barenboim was perhaps not on

quite the form to which Wagner can often bring him. There were a few

shortcomings to his conducting, for instance, a conclusion to the first act in

which he ran away with the orchestra, apparently leaving the chorus to fend for

itself. But on the whole, the score was in sure hands, with a conductor who

brought out not only the golden (Lohengrin-like?) string tone but equally a

frightening vision of madness in the brass fanfares of the third act, in which

orchestra, conductor, and director worked together to convey the terrors of

totalitarian militarism, especially that with a benign face. Such is a powerful,

if all too rare, example of how musical drama can and should work.

Mark Berry

Pictures © Karl Foster

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page