Other Links

Editorial Board

-

Editor - Bill Kenny

-

Deputy Editor - Bob Briggs

Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Offenbach,

Les Contes d'Hoffmann:

co-production

Teatro Real de Madrid et al, producer Nicholas Joël.

Soloists, chorus and orchestra of Teatro Regio Torino,

conductor

Emmanuel Villaume. Torino,

Italy. 4. 2.2009.

(MM)

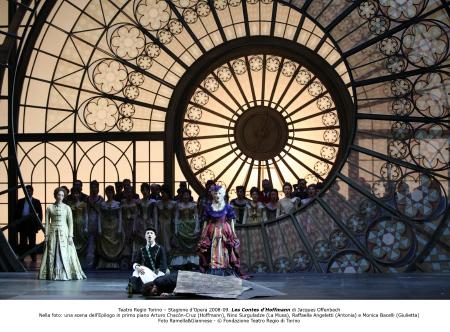

Puzzling,

the choice of London's defunct Cyrstal Palace (1851-1936) as the

backdrop on

which all of the action of Torino's

Les Contes

d'Hoffmann took place, as was indeed puzzling

the show curtain that

was a copy of poster for a side-show - a snake covered woman

suggesting, in

English, that we see the incredible snake lady and a gargantuan gorilla

too.

Perhaps

explicable since the august Teatro Regio has not had a lot of

experience with

the complications of Offenbach's masterpiece, the last Torino Hoffmann

some thirty-five years ago. Presumably this previous Hoffmann

occurred in

1973, the first season of the controversial, then new Teatro Regio (the

previous one having burned down in 1936), whose architect, one Carlo Mollino, had obviously

never been to an

opera.

If

stage director Nicolas Joël and his designer Ezio

Frigerio did seem to be off-track in their solutions, at

least the

Teatro Regio was mostly right-on with its singers and, particularly,

with its

conductor, Emmanuel Villaume.

After all, as

we were told by the charming young guide who showed us the theater that

afternoon, opera is only music, i.e. singing. Suspicions were

that it was

going to be just that anyway.

Poor

Hoffman was left lying on the forestage in front of the show curtain

during the

five-minute transition from Luther's tavern to Spalazini's workshop (a

window

panel of the Crystal Palace

was replaced by a

full-size choo-choo train locamotive). Young Mexican tenor

Arturo

Chacón-Cruz was singing his first Hoffman in these Torino

performances.

He is in the Carreras mold, the force of his sound heaved from his body

rather

than floated from his head. His voice never faltered through

these five

demanding scenes, his final prayer to the muse offered vocally rather

than

dramatically. This young tenor made his debut only in 2006,

and to date

has been heard primarily on important American stages. While

he boasts

considerable youthful vocal splendor he still offers only the promise

of a real

Hoffmann -- we need to wait until he has lived long enough to survive a

few

brutal love affairs of his own.

There

were some tense moments as Olympia spun around the stage on a remote

controlled

platform, and these movements contributed to this heroine taking the

prize for

the best performance of the three sopranos Torino used for this

production. Had Italian soprano Désirée Rancatore been left

on her own

she might have done as all the others did, simply stand downstage to

deliver

her role. As it was she ably delivered the vocal fireworks of

her

stand-alone showpiece while whirling around the stage, marred only by

some

shattering of tone in her above-the-staff

coloratura.

In

the Antonia act the choo-choo train was replaced by a pipe organ, the

purpose

of which, we learned, was to hide Antonia's mother from view.

Center

stage there were three instruments of a vaudeville orchestra.

Young

soprano Raffaella Angeletti gave us a fine, light voiced Antonia, even

her slim

figure could perhaps have been thought of as consumptive. She

pulled out

all her considerable stops for the big trio, though she had to compete

with the

vaudeville orchestra that came alive as performing skeletons.

Not

to mention the mechanical gondoliers that propelled a couple of

gondolas into

the Crystal Palace for the Venice episode (at least there was a lot of

dark

blue light). Giulietta

was sung by

soprano (the program calls her a mezzo), Monica Bacelli, who flounced

about the

stage as if she were a naive Carmen or a silly Donna Elvira rather than

a femme

fatale, though she delivered her scene with vocal finesse,

giving

considerable pleasure as the voice of Giulietta.

The

only disappointment was basso Alfonso Antoniozzi who failed to cut the

sizeable

figures required by Offenbach's four villains, nor did he bring these

flashy

roles alive vocally, perhaps due to a flu that had forced him to cancel

the

first two performances.

Nicklausse

was a victim of her costume (though all the other costuming seemed

reasonable). She appeared first as a Salvation Army rescuer,

in something

like a brass button uniform with an apron, and a small keg hanging over

her

shoulder. For the three episodes she became a man dressed in

tails, but

reappeared at the end again as the Salvation Army nurse turned

muse. Nino

Surguladze (a Georgian, thus the possible gender confusion) made this

role very

present, providing a mezzo

soprano vocal force

that was formidable, and bringing unusual physical liveliness to

Nicklausse. She was not able to muster the stature that the

muse needs to

end the opera effectively.

The

Nicolas Joël production was evidently about mechanical things, the 1851

Crystal

Palace a symbol of the mechanical technologies that were central to an

industrial revolution. With this idea pounded into our heads

throughout

the evening the fast tempos and the lightness imposed by French

conductor

Emmanuel Villaume seemed at first vapid and

mechanical. Mr. Joël's

stage tricks had served only to trivialize these three tales, thus the

purely

musical values emerging from the pit, values that strove to balance the

overwrought emotions of the libretto with the Offenbach muse, were

overwhelmed.

It

became apparent finally that maestro Villaume was walking the line

between

operatic parody and real opera, and between operetta and opera, a line

that

this maestro apparently finds to be very fine in Offenbach's

masterpiece.

The tempos and lightness did indeed make bona fide Offenbach music, if

not the

musically indulgent Hoffmann that we

self-indulgently crave.

Nicolas

Joel is said to have been ill, and unable to come to Torino to stage

the

singers, this task taken on by Stephane Roche. In short, Mr.

Roche lined

the singers up across the stage, and made a semi-circle of the chorus

behind

them. The appearance of Stella in the final scene was the

epitome of directorial

ineptitude.

The

program booklet did not credit the edition used, though presumably it

was the

2003 Keck version, complete with the twenty-six pages of recently

discovered

manuscript for which Mr. Keck is said to have paid 160,000 euros to the

French

government.

Michael

Milenski

Pictures ©

Teatro Regio Torino

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page