Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Stravinsky, The Rake’s Progress:

Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of

The Royal Opera, Thomas Adès : Conductor , Royal Opera House, Covent

Garden, London 7. 7.2008 (AO)

Like the Hogarth etchings of The Rake’s Progress, which so inspired

Stravinsky when he saw them in Chicago in 1948, the music in this

opera is stark and uncompromisingly spare : black and white, evoking

the moral absolutes in the fable, as much as the Hogarth prints.

It’s interesting to stage. The famous Glyndebourne production of

1975 used the concept of one-dimensional space, so the singers

seemed to jump out of the background like images jumping off paper.

That’s why this staging by the theatre artist Robert Lepage is so

engaging. It’s a spectacular riot of colour, wonderful on the

eye, yet it does bring out other significant elements in the opera,

which is what good direction should do.

Even more striking is the way Lepage creates the magic machine Tom

thinks will turn stone into bread and save the world (while making

him money). It’s a huge television set: feed the public illusion

and they’ll lap it up. As Nick Shadow says, it’s marketing. Inside

the set there’s a film of a small boy in a cowboy suit stealing a

plastic loaf of white bread, so synthetic it bears no resemblance to

real bread.

Baba is such a powerful character that she shines through no matter

what the staging. However, the auction scene doesn‘t have much

impact unless Baba’s role is more sharply delineated. In this

production, she disappears into the pool, which is fair enough, but

audiences who don’t know the plot might wonder why she’s resurrected

among the tawdry possessions being auctioned off. This too is a

crucial scene because it addresses another important theme in the

plot, that material things mean nothing in themselves. That’s

subversive, even now, and would have been all the more so in the

heady days of capitalism, after bleak years of war. Property is

theft unless you’ve earned it. You can’t buy virtue at an auction

any more than you can buy the Roman bust the auctioneer holds on

high. The crowd scenes were well choreographed, as is always the

case at the Royal Opera House, but in the libretto, the crowd is

evil, getting their kicks from Ton’s distress. Perhaps the black

costumes were meant to evoke vultures, which would be apt. But I

suspect they were meant to imply that Baba was dead, though she’s

not.

Cast:

Sally Matthews : Anne Trulove

Tom Rakewell : Charles Castronovo

Darren Jeffrey : Trulove

Mother Goose : Kathleen Wilkinson

John Relyea : Nick Shadow

Patricia Bardon ; Baba The Turk

Peter Brandon : Sellem the auctioneer

Joanathan Coad : Madhouse keeper

Thomas Adès : Conductor

The Royal Opera House Orchestra and Chorus

Robert Lepage: Director

Carl Fillion : Set designer

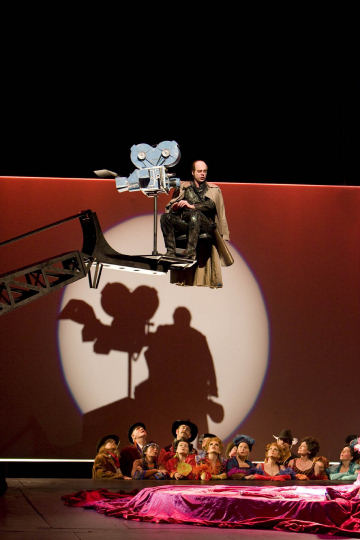

The Filming Sequence - John Relyea as Nick Shadow

The idea of transposing The Rake’s Progress to Hollywood is

perfectly valid as Stravinsky was fascinated by “the new world” of

America in the 1940’s and 50’s. The real drama in this opera is

between decadence and purity. Even Hogarth’s London is symbolic

rather than factual, so the idea of Hollywood is perfectly sensible.

As W H Auden said, the story is “A myth - it represents a situation

in which all men, at least potentially, find themselves in so far as

they are human beings”.

Lepage’s Hollywood setting is also valid because it captures the

fundamental anti-naturalism in the opera. Film isn’t reality, but

facsimile. Tom Rakewell’s mistake is to be taken in by surface

appearances, instead of true values. What you see is not what you

get. Nick Shadow convinces Tom that’s he’s a charming “servant”, but

he’s really the Devil. So Tom gets sucked in, even though at heart

he’s still basically a good person, as even Baba the Turk can see. The

Hollywood staging allows some wonderful moments. The first scene

comes straight out of Oklahoma!, the wide open horizon

symbolising the prospects before Tom and Anne. Even more

trenchantly, Nick Shadow is seen filming the action from up high on

a camera rig. He’s “directing” the other characters, pulling their

strings as though they are puppets. This expresses so well the sense

of devious plot within plot that runs through this opera. Tom

doesn’t notice the production crew with their booms and continuity

boards.

John Relyea (Nick Shadow) and Charles Castelnovo (Tom Rakewell)

However, the very spectacle of this production leads to weaknesses.

The brilliance of the first act starts to unravel in the scene where

Baba The Turk and Tom sit by the swimming pool. Maybe this is

Sunset Boulevard, but Baba is no deluded diva. The role may

seem small but it is in fact pivotal. Baba is a counterfoil to Nick

Shadow. He’s charming, she’s unloved. He’s seductive, she’s ugly.

He’s respected, she’s sneered at. Yet she’s the real heroine, even

more so than Anne Truelove. It’s she who sees through Nick and Tom

and helps Anne understand the heart of the fable. And it’s she who

can walk away from the disaster, because she has genuine strength of

character. Baba may babble, but Baba survives!

Patricia Bardon (Baba The Turk) and Sally Matthews (Anne

Trulove)

The lushness of this staging was impressive, and might have worked

even better had the music fought back better. To use the Hollywood

metaphor, this was a shoot out between staging and opera. Stravinsky

uses baroque orchestration for a purpose. This is music to listen to

if you don’t believe harpsichords can do extreme atonal dissonance.

Neo classical formality may shape the opera, but this is modern

music, where old serves new. Harpsichords are vulnerable voices,

easily overwhelmed. Just as virtue is vulnerable, overwhelmed by

vice. Stravinsky expresses the moral dilemma in his music. John

Eliot Gardiner’s recording brings out the chamber-like fragility in

the orchestral textures very well. Adès got good playing from this

orchestra, but his approach was more luxuriant, in keeping with the

lushness of the staging rather than acting as caustic counter

balance. In a more minimalist production, it would have been fine,

but here a bit more savagery would have helped. The Hollywood

Lepage evokes wasn’t paradise. McCarthy was hunting down artists and

destroying people who didn’t conform to the rampant capitalist ethic

this opera trenchantly derides. The Rake’s Progress is

disturbing and even subversive. But there was little sense of

danger in this production. For a moment, there was a hint of a

“mushroom cloud” exploding in the centre of the stage. But it turned

into a balloon shaped like a movie star trailer.

The singers, too, had to contend with the larger than life Hollywood

presence. Significantly, Sally Matthews, as Anne Trulove, stood out

well, for “innocent country girl” automatically undercuts

extravaganza. There’s less distraction around her role, so Matthews

come through more clearly. John Relyea’s Nick Shadow was strong

enough to stand out too, and was sung with magnificent menace. This

text is a challenge, conversational yet twisted, syntax and rhythms

wavering wildly. It’s not an easy part and needs someone like

Relyea who understands how it works. He will certainly be sing Nick

Shadow again as he’s still under 40 and it’s a role made for a voice

with this range of authority and subtle nuance. In a production

where more emphasis is placed on the singers, he would be

exceptional.

This Rake’s Progress is definitely worth experiencing as it’s

very different. Friends of mine who attended shared my misgivings

about its representation of the music, but as theatre it works

extremely well. Indeed, a good friend of mine who didn’t know the

opera before was absolutely thrilled. That’s a very good thing

indeed, as any production that can make someone want to find out

more and listen again deserves respect.

Pictures ©

Back to Top Cumulative Index Page