Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD FESTIVAL PREVIEW

The Music of

Olivier Messiaen, From the Canyons to the Stars:

A report from Anne Ozorio,

South Bank Centre, London, 1 February – 10 December 2008 (AO)

“This is the most comprehensive Messiaen retrospective ever” said

Gillian Moore, Head of contemporary culture at the South Bank.

She’s right. This is a festival of international significance,

which will be remembered as a landmark for many years to come.

Olivier Messiaen’s influence cannot be underestimated. He bridges

tradition and innovation. Indeed, Messiaen is a key to

appreciating most European music since the mid 20th

century.

Monumental works like Turangalîla-symphonie, and La

Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ aren’t heard

often enough live because they require such forces, but they are

so spectacular that they can’t be missed. Aimard himself is

playing another tour de force, Vingt Regards sur

L’Enfant-Jésus. It will be an experience no recording can

quite match. A newly-published piece for piano and violin,

Fantaisie, is being premiered. The famous Quartet for the

End of Time gets two performances. Only the opera, St

Francis of Assisi, is missing. Sometimes, it’s just not

possible to overcome “the charm of impossibility”, a phrase

Messiaen himself created. It’s good that we already have so much.

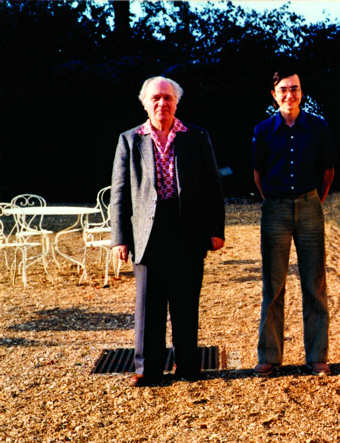

Olivier Messiaen (left) and Pierre-Laurent Aimard

The Festival Director is Pierre-Laurent Aimard. “We met”, he says

modestly, “because my piano teacher was Mme Loriod”. He was twelve

years old. Mme Loriod was Messiaen’s muse, collaborator and

partner for nearly 50 years. Indeed, it is because Aimard was so

close to the composer that this Festival is unique. On 2nd

February, Aimard and George Benjamin, who met Messiaen aged 17,

discussed their personal memories of Messiaen’s personality. He

was so charismatic that they learned a lot more from him than

“just” music. He was an unworldly figure, who could sit “serenely

calm” for hours on end, “like a rock”, but was always listening

acutely. What might seem to others as his naivety springs from his

innate simplicity and purity of spirit.

He was also systematic and objective. He had 12 pairs of

spectacles lined up, each for a specific purpose. This translates

into his music, where every little detail is there for a reason

and must be clearly defined. Messiaen often used the image of a

stained glass window to describe his work. A stained glass window

is magnificent because light shines through it, making it a blaze

of myriad colour. Yet it is made of numerous individual fragments

of glass, each unique, depending on their hue, density of glass,

angle of placement etc. Moreover, as light changes, the colours

reflect and refract differently : nothing remains unchanged even

though the glass itself doesn’t move. It is a wonderful metaphor

for what happens in Messiaen’s music.

Aimard also knows everyone connected with the composer. This is

about as authoritative a festival as there is ever likely to be.

Mme Loriod may not be playing, but Aimard, Uchida, Latry and

Salonen will be there, and Pierre Boulez, perhaps one of

Messiaen’s closest associates, will be conducting the keynote

concert on the very day of the composer’s centenary, 10th

December.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard - Picture © Guy Vivien

Another special feature of this Festival is that it places

Messiaen’s music in context. He was a highly spiritual person,

for whom music was an expression of profound faith. The Festival

actually started with a conference on music and spirituality.

Although Christian symbolism infuses most of his work, his is a

spirituality which transcends specifics, seeking a higher

communion with the very essence of belief. Stockhausen, Boulez,

Pärt, Grisey, Takemitsu and others may not write “Christian” music

as such, but their work is enhanced by this powerful sensibility.

Messiaen’s interest in birdsong, nature and non-western cultures

stems from the idea that God is in all things. Similarly, his

interest in synaesthesia comes from the idea that sound and sight

connect intuitively. On 15th February, there’s a forum

on interpreting visual images in performance.

Messiaen himself played the organ nearly every day at the Trinité,

so his music for organ will feature prominently later in this

Festival. The South Bank will include “North Bank” venues such St

Paul’s Cathedral. The great organ at Westminster Abbey will be

used for a performances of Apparition de l’église éternelle

and La Nativité du Seigneur by Olivier Latry, who will also

be giving a masterclass. Organists don’t often get so many

chances to gorge themselves on feasts like this.

Three days a week, Messiaen devoted to teaching, because he

believed so strongly in the value of nurturing talent. Many

events are taking place at the Royal Academy of Music, inspiring a

new generation. This is particularly good programming, too,

because it means many smaller works can be included. Also being

performed are works by those whom Messiaen learned from, such as

Dukas, and those he taught. Gerard Grisey’s superb Les Espaces

acoustiques receives its long overdue UK premiere on 14th

October. Messiaen taught the teenage Boulez, and used his music

to teach others. Messiaen’s Et exspecto resurrectionem

mortuorum is being performed with Boulez’s Rituel in

Memoriam Bruno Maderna, a composer whom they both knew.

A very good example of Aimard’s enlightened approach to this

Festival was the Study Day on the Quatuor pour le fin du Temps,

held on 3 February. Aimard gave a cogent analysis of the work,

playing “Messiaen chords” on the piano to demonstrate. The basic

cells shift imperceptibly, “like the turning of a kaleidoscope”.

Values change, rhythms change and sometimes there are extra notes.

“It is a game of permutation, a game of time”, he says. This is

nothing like Bach, or the kind of conventional polyphony we’re

used to. Messiaen’s polyphony exists as if in suspension.

Layers don’t depend on relationships to interact, but flow of

their own volition. This is “the music of immateriality”,

defying concepts of time and movement, a radical approach to

fundamental assumptions on the nature of music. He had Paul

Watkins and Marianne Thorsen play the violin and cello first as

Messiaen suggested, then in conventional mode. Watkins also

demonstrated how the notorious cello passage is played, so close

to losing the legato. Time and sound are stretched to their

limits.

Cameras were in the hall to film the proceedings. What will

eventuate will be interesting. In another time warp Messiaen

would have enjoyed, there was a first screening of a new,

unreleased film about the Quartet for the End of Time.

Titled The Charm of Impossibility, it describes how the

piece came to be written. It was filmed in Görlitz in Silesia, on

the site of the former POW camp. At first it seems as if the huts

in the camp are being shown. Then the camera moves. What’s

being filmed is just a scale model. A former POW walks around the

trees where the camp used to be. All traces are gone, and he says

“I’ve lost my bearings”. That in itself is a good metaphor for

what the music is trying to express.

There’s a reconstruction of what that first performance might have

sounded like, where the prisoners played on broken, tuneless

instruments. The film makers found instruments of the right

vintage, with similar defects. The cello strings were so worn they

had almost no vibration, and one of the piano keys was broken,

just like the one Messiaen used. The musicians even wore the same

kind of wooden clogs the prisoners wore. These make a cracking

sound as they move on the wooden floor. It must have been

interesting to manipulate the pedal of the piano. The film ended

with another performance with conventional instruments played in a

ruined building. When the violin holds its last long notes as the

piano fades into silence, the film merges the image of the stage

with the image of the bare stone walls. Gradually we see less and

less of the musicians, as their image merges into the abstraction

of the wall. Then all we see is the impenetrable surface of the

stone itself. Again, this expresses the granite like angularity in

the music, the strong Angel from the Book of Revelation, and the

idea of Time itself, paradoxically changing and unchanging.

The Nash Ensemble returned to play the Quartet through

uninterrupted. I couldn’t, however, shake the image of the filmed

reconstructed POW performance in its harshness and desolation.