Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Busoni, Doktor Faust:

Bavarian State Opera, Opera Festival 2008:

Soloists, Bavarian State

Opera Orchestra, Kent Nagano (conductor) Nationaltheater, Munich

28.6.2008 (JFL)

Production Team

Nicolas Brieger (direction)

Roy

Rallo (assistance)

Hermann Feuchter (sets)

Margit Koppendorfer (costumes)

Alexander Koppelmann (lighting)

Doktor Faust

Wolfgang Koch (Doktor Faust)

John Daszak (Mephistopheles / Night Watchman

Raymond Very (The Girl’s Brother, Duke of Parma, Megäros, Ghostly

Voice V)

Steven Humes (Wagner, Gravis, Ghostly Voice I)

Catherine Naglestad (Duchess of Parma)

Alfred Kuhn (Master of Ceremonies)

Further:

Adrian Sâmpetran, Ulrich Reß, Christian Rieger, Klaus Basten,

Rüdiger Trebes, Kenneth Robertson, Jason A. Smith, Marcel Görg,

Werner Bind, Ingolf Kumbrink, Jochen Schäfer, Elif Aytekin, Laura

Rey, Stephanie Hampl

In turns grim and fantastical, Wolfgang Koch (Doktor Faust), John

Daszak (Mephistopheles), Raymond Very (Duke, Valentin – “the Girl’s

brother”, et al.), Catherine Naglestad (Duchess of Parma), and

Steven Humes (Wagner) sang and acted their way through this beastly,

beautiful work that engulfs the senses with renaissance sounds and

chorales, a romantic chromatic haze, expected Wagnerian touches and

unexpected moments of Offenbach. Steven Humes had little voice-time

to showcase his skills, but his strong, blooming baritone pushed

Wagner – who later takes over Faust’s job as Rector magnificus

– to the forefront. Koch’s baritone carried well and never tired.

His and Daszak’s performance are primarily the ones where effort

turned into achievement and achievement into something

extraordinary. Daszak who gave Mephistopheles his tenor, was

piercing in his comfortable range, offered a positive sense of

struggle here and there, and was covered by the orchestra only early

on. The female relief of the opera, Catherine Naglestad, charmed

the audience with strong singing and acting, even with a strong

metallic vibration in her voice. No one else exceeded, or fell short

of, reasonable expectations and requirements.

Composers, too, have been inspired – usually via Goethe: Wagner

wrote a Faust Overture (not his most inspired moment), and

Liszt the

Faust Symphony.

Mahler’s

Eight Symphony

bases its second part on Faust II. Schubert composed the Lied

“Gretchen

am Spinnrade”, and Schumann his overly ambitious,

terrifically strange (and strangely terrific) Scenes from

Goethe's Faust. (The good recordings –

Herreweghe,

Abbado,

Klee

– are out of print, but a new one with

Christian

Gerhaher might be recorded soon.) Lili Boulanger

contributed a half hour cantata

Faust et Hélène,

Dusapin

Faustus, The

Last Night (owing more to Marlowe than

Goethe). Prokofiev’s

Fiery Angel,

Stravinsky’s

The Rake’s

Progress, and even Adams’ Doctor Atomic

are adaptations – albeit loose ones – of Faust.

“Only Mozart” (who had already died), did Goethe proclaim as

capable of writing an opera of his Faust – but that did not

keep others from trying. Arrigo Boito succeeded most resoundingly

with

Mefistofele,

Berlioz’ “légende dramatique”

La Damnation de

Faust offers the most boldly literal operatic

take, and Gounod’s

Faust

(formerly known as Maguerite) makes it an example of how

grand French opera should be.

“German” (in the loosest sense) composers must have found the

Goethe-model a little too daunting. First Louis Spohr (“Faust”),

most recently Alfred Schnittke (“Die

Historia von D. Johann Fausten”), and in between

Ferruccio Busoni with

Doktor Faust

all tackled the subject from different directions. Busoni used the

16th century puppet plays – the same source that inspired

Goethe – to avoid direct comparison. But he also drew on Heinrich

Heine’s

Der Doktor Faust

– Ein Tanzpoem and very likely on

F.T.Vischer’s Faust III.

From these sources Busoni created one of the great German 20th

century operas, an opera that is finally catching on with recent

performances in New York, San Francisco, Stuttgart, Zurich, Berlin (Unter

den Linden), and now Munich, where it opened the

2008 Opera

Festival. Director Nicolaus Brieger (with Hermann

Feuchter’s sets, Margit Koppendorfer’s costumes, and Alexander

Koppelmann’s lighting) achieved the small miracle of staging

Busoni’s magnum opus for the festival premiere without incurring any

of the near-customary “boos” that accompany them. If the lack of

vocal disagreement was accompanied by slightly less than

enthusiastic cheering, it might have been because many ears had

difficulty digesting the nearly three hours of Busoni’s music – even

80 years after its premiere.

In Zurich, Philippe Jordan turned the orchestral score into the

highlight next to the superb, fittingly haughty Faust of Thomas

Hampson’s. In Munich Tomáš Netopil, winner of the first Sir Georg

Solti Conducting Competition, navigated rather dutifully through the

score, neglecting nothing and offering – occasionally – gripping

moments. The main attractions were Brieger’s direction though, the

successful effort and achievement of the singers, and most of all

Busoni’s opera itself.

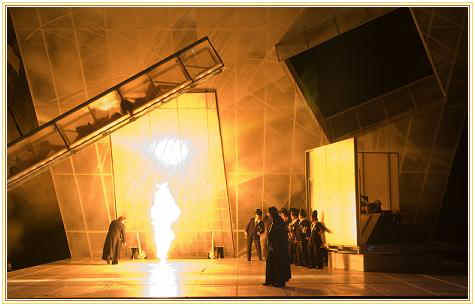

Perhaps because there was much staging to pay attention to: Faust

and his puppet-likenesses (wonderfully animated by Peter Lutz, Lutz

Grossmann, and Rike Schubert); the set that looks like Rem Koolhaas

meets Starship Enterprise; the vaguely Wehrmacht-like soldiers who

drill organ pipes through Valentine’s body when Mephisto has him

killed on the altar; and especially the naked, bronzed demons that

dangle above Faust as he summons Lucifer’s servants Gravis, Levis,

Asmodus, Belzebub, and Megaros. That last being the most iconic

scene of the production – a visual coups de théâtre.

Mephistopheles himself is the red-gloved, wig-wearing seducer who

dons a bikini-top on his bulky, hairy frame. The grotesque androgyny

doesn’t last long, thankfully, but long enough to start wondering

just how real Mephistopheles is to Faust, and how much he is a

figment - a creation- of his will and imagination. From there, Faust

moves toward ‘will and realization’ of having left convention,

society, and morality so far behind that no redemption is possible

for him. His prayers impotent, he heaves himself beyond categories

of good and evil, God and Devil. He manifests himself (or wishes to

do so) in ‘will’ itself. The bubble of grandeur, if there is one, is

pricked immediately when Mephistopheles, in the guise of the Night

Watchman, finds Faust’s corps and drags him away, sardonically

stating: “Should this man have been met with misfortune?”

A visual feast and auditory joy, the Munich Doktor Faust –

played in the original, unfinished version, not the Jarnach or

Beaumont completion – is not a production for the ages, but it will

do much in bringing this fascinating composer back to the opera

stages where he deserves to be much more often. And eventually not

just with Doktor Faust but also –eventually– his Turandot,

Die Brautwahl, and Arlecchino.

All

Pictures © Wilfried H

Back to Top Cumulative Index Page