Bayreuth

Festival 2007(2) Wagner, Tannhäuser und

der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg :

in a revival by Philippe Arlaud, sets by Philippe

Arlaud, costumes by Carin Bartels, Soloists, the

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra and chorus, conducted

by Christoph Ulrich Meier. Bayreuth Festival, 18.

8.2007 (JPr)

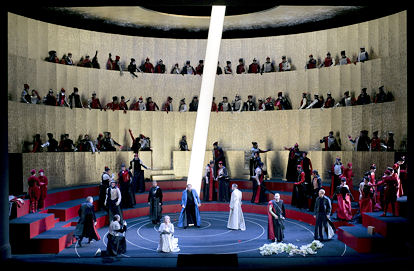

Tannhäuser Act II Picture © Jochen Quast

This was the next Bayreuth performance after

Die Meistersinger and many in this audience

would have been at both. The storm of applause and

the foot stamping that the singers, chorus and

conductor received, not only seemed to an

appreciation of their efforts but also a protest

against what the audience had had to sit through a

couple of nights earlier.

For me in hindsight, I would have preferred to

see these two operas the other way round.

Tannhäuser would have been the perfect

antidote had I found Die Meistersinger like

the person sitting next to me ‘lamentable’. I did

not. I was impressed by the honesty and bravery of

that production (review), if left a little confused by some of

the imagery and ideas. So it was that I was a bit

spoilt by Katharina Wagner’s new staging where

more happens in one minute than in the whole of

Act I of Philippe Arlaud’s Tannhäuser

lasting just short of one hour. While there is

room for both approaches - this dichotomy is a

fundamental part of where Bayreuth goes in the

twenty-first century - personally I am beginning

to prefer too many ideas rather than none at all.

What we get with this Tannhäuser is

virtually just a costumed concert. Over the years,

because of Workshop Bayreuth there may be a

little more movement in it than when I first saw

the production in 2002, its first year, but it

still remains rather too static and devoid of any

interpretation.

Philippe Arlaud’s icy Venusberg looks like the

open laptop on which I am writing this review. The

audience has just spent about 20 minutes staring

at the closed curtain and should really feel

short-changed without the orgy that is sometimes

choreographed, even though we are hearing the

original

Dresden

version. Here Tannhäuser

is made to clasp Venus’s breast and they get into

a clinch. Arlaud shows just three sirens in the

background each revealing a shapely leg and that

is about all there is to look at until Tannhäuser

sings ‘Mein Heil liegt in Maria!’ and the set

flies away into the background in the magical

manner that

Bayreuth’s magnificent stage machinery allows.

Now in the Wartburg valley, we are in Tellytubby

land or a vast grassy bower with ‘pasture’

covering floor, sides and ceiling, all studded

with red poppies. The sweet voiced Shepherd (Robin

Johannsen) freshly and plaintively sings ‘Frau

Holda aus dem Berg hervor’. The song of the

Pilgrims is heard in the distance and they enter

on their way to Rome, stand around and sing, then

leave down a subway tunnel under the front of the

stage. The Landgraf’s hunting party enters like

refugees from any routine staging of the ballet

Giselle, complete with stuffed carcases.

Everyone stands around again and sings until Frank

van Aken (Tannhäuser)

- who begins the Act singing loud and just gets

louder and a touch coarser - sings ‘Zu ihr, zu

ihr!’ and sets off to find Elisabeth.

Although I have seen Tannhäuser

several times, the debt it owes to Fidelio

has never been so obvious. Two examples suffice:

listen to the Tannhäuser/Venus

duet when he sings ‘Nach Freiheit, Freiheit dürste

ich’ and to Tannhäuser/Elisabeth

when they sing ‘Gepriesen sei die Stunde’ : there

is the music of Florestan and Leonore plain for

all to hear.

Arlaud’s hall of the Minstrels in the Wartburg

Hall is all gleaming gold, intense reds and black,

colours that are later mirrored in the rigid

costumes of the guests, with the knights

distinguished by bits of armour. Again, there is

not much contact between Tannhäuser

and Elisabeth, although there is some hand-holding

during the song contest which scandalises the

guests present. These onlookers react with

stylised movements throughout and when Walther

sings, someone high up swoons and then he is

showered with flowers. Of course, Tannhäuser's

sins are soon revealed because not only has he

enjoyed the erotic delights of being with the

goddess Venus but he now feels the need to brag

about this in the presence of his true love,

lustily extolling the pleasure of being with Venus

in front of the whole court. At this point Tannhäuser

walks back and forth across the stage clutching

bouquets of flowers but at least something is

happening on stage.

Only Elisabeth’s passionate intervention (‘Zurück

von ihm!’) prevents the indignant knights of the

Wartburg from killing

Tannhäuser

on the spot, but yet again everyone is standing

still to hear her plea. Elisabeth has already

begun to lose her mind and is giving up on life by

this time but the Landgraf has the answer; send

Tannhäuser to Rome, to beg Christian absolution

for his pagan blasphemy. A great chorus rings out

before Tannhäuser’s ‘Nach Rome!’

In Act III we were back invading the territory of

the Tellytubbies but a yellowish light gives it

all a more desolate appearance: later there is a

blue light to guide Elisabeth’s soul heavenwards.

For me all the emoting, standing around and

singing was rather soulless. The Pilgrims enter,

stand, sing, then leave. Tannhäuser has

not found absolution and comes back from Rome

crushed and in the deepest despair. He throws

himself around the stage during his Narration

explaining how if only the Pope’s wooden staff

should bloom again will he be pardoned for his

epic sins. This is of course what happens but it

will be too late for him and Elisabeth. Venus

reappears and is about to reclaim her victim when

Wolfram evokes Elisabeth’s name and Tannhäuser is

freed from Venus's clutches at last. His final

exhausted ‘Heilige Elisabeth, bitte für mich!’ is

actually quite affecting. Eventually all is green

again as the Pope’s staff with its new

shoots is shown and everything reaches its

redemptive conclusion: one soul is saved by

the death of the blameless woman (Das Ewig

Weibliche).

Judit Nemeth’s Venus was surprisingly

passionate, compelling and seductive considering

she was restricted mostly to semaphore-like gestures. She and Ricarda Merbeth’s

Elisabeth produced big, loud tones athough Merbeth’s ‘Dich,

teure Halle’ lacked the certain finesse I was

always told to listen out for when auditioning

young artists. Happily, sShe scaled down her voice for an

affecting ‘Allmächt’ge

Jungfrau’ that was as lovely and prayerful as it

should be. Roman Trekel’s Wolfram von Eschenbach

was magisterial, an honourable yet strangely

introspective man who sang ‘O du, mein holder

Abendstern’ as though it was from a book of

Lieder: this was nuanced and full of detail,

qualities which characterised his singing throughout the

whole evening.

Guido Jentjens also shaped each of his lines with

profound insight and great warmth but his diction

seemed poor. The principals were supported by some

stout singing from the minor minstrels and the

always excellent chorus, confined as they were

to being groups of pilgrims or filling

the balconies of the Wartburg Hall.

Absolved of any doubt or criticism was Christoph

Ulrich Meier, a late replacement for Fabio Luisi

as conductor. (Maestro Luisi apparently had an

‘acute back ailment’ although this does not seemed to have

stopped him conducting before the festival or

having plans for early September).

Meier was once assistant to and protégé of Christian Thielemann

and his intense reading transparently

revealed facets of the work rarely heard

with such clarity and intensity. The orchestra’s

playing began on a high with a Prelude which

reached an orgasmic climax and from

that point onwards it continued to play with pure Bayreuth magic.

Another last minute replacement was the Dutch

tenor, Frank van Aken, as Tannhäuser

who had come in during June to replace Wolfgang Millgram. Though

this character is perhaps the most

passionate, revolutionary and morally-challenged

in all of opera, van Aken sang him as an

out-and-out hero with little doubt,

internalisation or apparent identification with the

role. Perhaps the director did not have enough

time to help him? If he had been auditioning for

Tristan then he did a good job but his voice

though powerful to the end, has a worryingly

unschooled quality about it which makes me

doubt that he will extend his varied career of lyric

and lighter heroic roles much if he sings too

much heavy Wagner.

For those who booed Katharina Wagner’s Die

Meistersinger or were perhaps on the Green

Hill for the first time this production was a

glimpse of

Bayreuth

of yesteryear. An abstract production with

admittedly exciting ‘stand and deliver’ singing

but as we go towards the 200th anniversary of

Richard Wagner’s birth is this all we (or he

) would really want, I wonder? We should be

prepared to have our intellects engaged and not be

willing to watch a production that could have,

with a bit of tweaking, been used not just for

Tannhäuser,

but for Lohengrin, Tristan und

Isolde (just) and Parsifal.

There are complex conflicts here that Philippe

Arlaud did little to explore and, I repeat, it is

better ( in my opinion) to have too many ideas in

a production than none at all.

Jim Pritchard

Back

to the Top

Back to the Index Page