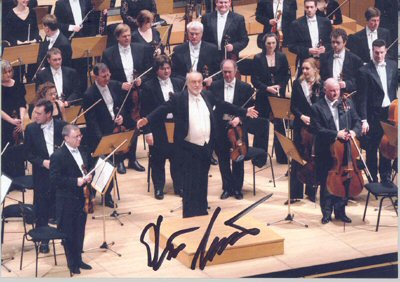

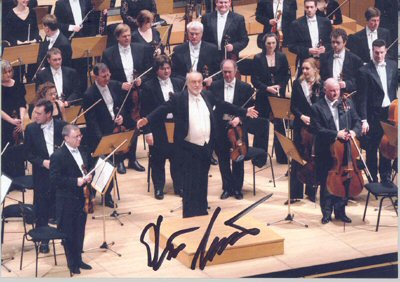

Seen and Heard

International Concert Review

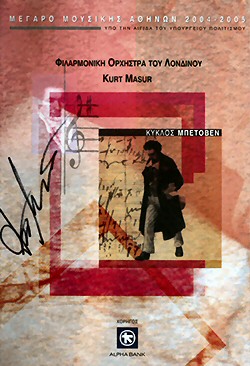

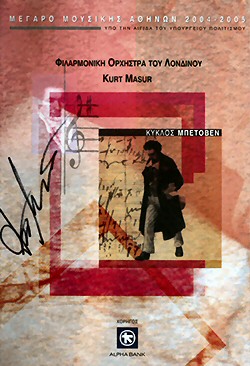

The London Philharmonic Orchestra in

Athens: Beethoven Cycle, Soloists, London Philharmonic

Orchestra, Kurt Masur, Megaron, Athens, 12th to 15th January 2005

(ARi)

Ludwig van Beethoven:

Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 (1800)

Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 (1802)

Symphony No. 3 "Eroica" in E Flat Major, Op. 55 (1803)

12th January 2005

Symphony No. 4 in B Flat Major, Op. 60 (1806)

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1807)

13th January 2005

Symphony No. 6 "Pastoral" in F Major, Op. 68 (1808)

Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 (1812)

14th January 2005

Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93 (1812)

Symphony No. 9 "Choral" in D minor, Op. 125 (1824)

Christine Brewer (soprano)

Carolin Masur (mezzo soprano)

Thomas Studebaker (tenor)

Alastair Miles (bass)

London Philharmonic Choir

Manolis Kalomiris” Children Choir

15th January 2005

After an unsuccessful attempt to present the complete Beethoven

symphonies in Athens two years ago, and after the very good Brahms

cycle of last year, the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Kurt Masur

offered the Athens audience Beethoven’s symphonic legacy in

four sold-out concerts.

In the opening movement of the First Symphony the orchestra’s

reading was elegant but Masur’s approach, despite the very

fast tempi, failed to convey the overall feeling of gaiety and happiness.

The same was also true of the third movement, except perhaps for

a very successful dialogue between the winds and strings in the

Trio. The final movement was the most successful of all with beautiful

phrasing from the second violins.

The Second Symphony’s slow introduction brought with it gentle

statements from the winds and the main theme of the allegro

con brio section underlined beautifully the energetic and cheerful

character of the music. The lyrical theme of the second movement

had grace, lightness and exceptionally well-phrased statements from

the horns and bassoon. After an indifferent scherzo, a perfect,

thunderous rondo followed, its impressive first theme performed

furiously, as it should be. Clarinet and bassoon introduced lyrically

the second theme, and this was well contrasted with the explosive

repeat of the first theme.

The introductory first two chords of the Eroica were played

in tempo and with weighty significance; but the main theme simply

lacked heroic tension. I have never understood how - and why - certain

conductors appear so restrained here, as if they are not overwhelmed

by this stormy music. The orchestra’s playing was largely

without contrast, and this was especially so when the second theme

emerged from the winds to be taken up by the first violins. The

recapitulation featured very good playing by the horns, however.

The Funeral March was understated and the crescendo not

sufficiently weighty. The third movement was very well articulated

but the winds solos were quite often approximate; pizzicati in the

finale’s introductory theme were impressively accurate. However,

this was a performance which gave little, or no, opportunity to

experience the score’s triumphant character.

The joyfulness of the Fourth Symphony’s introductory movement

did not emerge in Masur’s reading, which appeared stiff and

lacked a bel canto quality. However, the flute was exceptionally

fine and the string attacks well rehearsed. The slow movement enraptured

the audience immediately; it remained totally silent throughout

its duration. Both orchestra and maestro were incredibly concentrated

and offered us moments of pure emotion and tenderness. The Scherzo

was played satisfactorily but without any contrasting effects between

the minuet and trio. The finale lacked the enthusiastic treatment

I prefer in this work.

The Fifth Symphony’s first movement received a fabulous, straight-forward

reading full of genuine passion and fire; miraculously, Masur left

the orchestra time and space to breathe. The serenity of the following

movement was happily interrupted by a powerful, and elaborately

phrased crescendi. The scherzo was introduced by dark and warm celli

leading to a quite impressive performance of the fugato Trio section.

The transition to the final movement was in the spirit of Masur’s

overall conception of this particular work, avoiding the rallentandi

very often used (and misused) by others in this section - although

I was tempted to prefer a little more suspense. The final movement

was full of character, brio, grandeur and orchestral precision;

a real delight for the mind and the heart and the peak of the cycle

so far.

The third day opened with the Pastoral. The introductory

movement was played in an ideal tempo, and both orchestra and conductor

stated the popular themes nicely with great playing from the strings.

The second movement advanced steadily and in an unaltered tempo

until the end, with beautiful contributions from the wind soloists.

The horns sounded a little too loud in the third movement but had

a charming and warm tone. The tempest burst naturally - but not

wildly – with Masur preferring to let the music to speak for

itself. The finale, unfortunately, was rather cold and indifferent;

if only the orchestra’s strings and admirable woodwinds hade

been allowed more involvement!

The poco sostenuto introduction to the Seventh Symphony

should have been more involved and sustained in order to contrast

with the flute solo (played without grace) in the exposition of

the principal theme of the movement’s main body. But these

were the only unwelcome aspects of Masur’s interpretation

and the orchestra’s performance; it emerged into an unforgettable

experience. Incredible tutti were sung and danced in lively tempi,

bringing us into a world of total happiness and joy. In contrast,

the ritual dances of the second movement were very strict rhythmically

and were supported by an orchestra in exstasis. The scherzo was

performed brilliantly, respecting the presto indication set by the

composer, and if the Trio was on the fast side it was notable for

a great contribution from trumpets playing to their limits. Almost

without a break - and without any sign of fatigue - the orchestra

released their rich reserves and offered us a fast and generous

conclusion to this symphony. A technically impressive and exhilarating

account that will linger long in the memory.

The Eighth symphony, which opened the last day

of this cycle (preceded by a welcome greeting in Greek from Kurt

Masur to Mikis Theodorakis who was present in the hall), seemed

to be less well rehearsed than the others since quite often we encountered

unclear sonorities and weak balances. Nevertheless, the second movement

was noble and gentle, and masterly constructed and executed. The

third movement suffered from some orchestral inaccuracies and it

was unfortunate that the horns sounded insecure. The final movement

succeeded only due to the strings’ impeccable playing.

The first measures of the Ninth defined the grandeur of the performance.

Lively tempi, together with a sense of understanding of the movement’s

complex inner architecture, gave this movement the epic character

it deserves. The sharp fortissimo beats that introduced the second

movement, together with the impulse and power that governed the

scherzo, convinced me that his Ninth would be the best I had ever

experienced in a concert. The slow movement was notable for disarming

phrasing and simplicity. The second violins and violas could not

have underlined any better the serenity of the divine second theme,

this masterpiece’s humanitarian message being clearly conveyed

to the audience. I think Masur managed to find the golden rule between

the late romantic and historically informed approaches. Without

metaphysical demonstration, the orchestra stated dramatically the

“fanfare of terror” and expressed perfectly all the

movement’s different moods until the first statement of the

main theme, “Ode to Joy” on the woodwinds. The quartet

of soloists had a rare homogeneity, which was immediately noticeable.

Together with the incredibly accurate Choir we lived moments of

grace, inspiration and happiness. The audience honored this important

event with long ovations and as the Maestro told me backstage he

wishes to come back next year with a Schumann cycle.

Alexandros Rigas