S & H Opera Review

Wagner, The Valkyrie (new production), Soloists, ENO, Paul Daniel (cond.), 8th May 2004 (MB)

After a less than successful start to English National Opera’s new staged production of the Ring cycle, a Rhinegold which I described at the time as "dull", "unimaginative", "undramatic" and one which was "cast unevenly and… conducted flaccidly", the company has redeemed both itself and the long-term future of its cycle with this outstanding new production of The Valkyrie. If not flawless, it is played, sung and staged with a degree of conviction which was conspicuously lacking in the first part.

The opera starts, not quite with Wagner’s rampant ‘cellos and basses rumbling beneath tremolo strings (one of the greatest of all opera openings), but with Sieglinde filling the vaults of the opera house with a piercing scream. It’s a startling beginning and one directorial touch among many that sets this production apart from Rhinegold. Whereas the latter concentrated on giving us an urban surrounding for our Gods that was determinedly Thatcherite in its politics of human neglect and greed, Valkyrie places our mortals in a world decimated by conflict. The upturned tree, with its sprawling roots, a gun-toting Hunding and Brünnhilde, militaristic valkyries and slain hoodlum paratroopers hint at universal conflict and unrest – although one could argue that Lloyd sees it as regionalised with her Sieglinde dressed as a Muslim imprisoned by a combat-clad Hunding. Wotan – in white-tie – and Fricka – with briefcase and power-dressing suit – recall the weaknesses of Rhinegold but in most instances the transposition of the opera to its current setting is a convincing one.

Act I, the weakest of the three in this new production, begins in Hunding’s hut – perhaps more accurately a bunker. It is simplicity itself, scantily decorated – much as Wagner suggested in his libretto - but when Sieglinde sings, "You are my spring" the back opens up onto an emerald green landscape that sends a halo of light into the auditorium. It is the only moment of lightness in a scene which is drearily depressing. Siegmund and Sieglinde consummate their love as silhouetted figures writhing passionately on a table, a phallic sword drawn from between her loins. These are not equally matched siblings, however. Pär Lindskog, as Siegmund, looks heroic but sounds anything but that. Too often his voice projects lyrical cloudiness and his pitch is almost constantly flat. His cries of "Velsa! Velsa" (here reduced to a singular "Velsa" in the new libretto – why?) fail to ignite as they should. Orla Boylan’s Sieglinde, in contrast, is stoically trenchant in her singing, a formidable bride for her brother, and capable of ecstatic lyricism in her final scene.

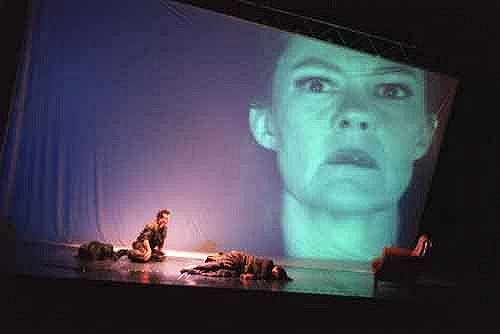

Lloyd’s vision reaches its apex in this production with the second act, an impressive visual experience that does much to supplant some below par singing. Robert Hayward’s Wotan – if still suffering from that monochromaticism of tone that almost wrecked Rhinegold – is here more brutish in his delivery. But firmness of tone does not a Wotan make, and throughout the act the lack of colour to the voice sometimes gives the effect of undermining Wotan’s moral authority. Sat impassively in his armchair – with a clinging Brünnhilde folding herself around him – the first suggestions of their own incest which Lloyd realises more starkly in Act III – he watches on the ‘big screen’ Hunding’s hunter-like instincts in tracking down Siegmund. ‘Filmed’ as a vast silhouette, and giant-sized at that, Siegmund’s death recalls any number of screen equivalents – from Psycho through to Tenebrae. Less convincing use of the screen is perhaps in Brünnhilde’s Todesverkündigung where much of the ominous impact of the scene is lost, splendidly though Kathleen Broderick sings it.

Act III begins with paragliding valkyries and the descending torsos of lost warriors – dirty vests and helmets all being a little too suggestive of gay cartoon iconography. Chorography is not always clean – at times one was reminded of stilted action men, but it is convincing on its own artistic level. Less convincing is perhaps the greatest scene in the opera – Wotan’s and Brünnhilde’s last act duet. In part the clinical whiteness of the hospital setting detracts from the very emotiveness of this farewell, with Brünnhilde’s sleep - by injection - reverting back to the image of the Gods’ drug-withdrawal in Rhinegold. Yet, both Broderick and Hayward reach levels of singing that only the Hunding of Clive Bayley has previously achieved. One might have wished for a greater sense of legato in Hayward’s voice but he reserves his best singing for the Farewell nevertheless. Their final embrace – and incestuous kiss – before Brünnhilde is encircled by fire (here a molten reddening of the stage amidst billowing smoke) has a momentary passion to it which eclipses that of the Walsung twins in Act I.

The singing is largely well done throughout – even if diction often goes for nothing. Orchestrally and musically, however, this is an improvement on Rhinegold. After Paul Daniel’s lumpen conducting of the prelude to the Ring his pacing of Valkyrie is exemplary. True, he takes a deliberate pace at the opening of the opera (hear Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic in 1968 for a simply wild opening) but it is gripping and the playing is sufficiently weighty enough. Tempi can be blistering – the opening to Act III, for example – but Daniel is also attune to the lyrical moments in the score. The climax to The Farewell is ecstatic, reaching a tidal wave of eroticism at its close. Throughout, the ENO orchestra play with superb control and tonal brilliance. As with Rhinegold, lighting is impressively done by Mark Henderson and Richard Hudson’s designs, more successful than they were for the previous instalment of this cycle, are never less than eye-catching, and often more than that.

Marc Bridle

Further Listening

Wagner, Die Walkürie, Soloists, Wiener Philharmoniker, Wilhem Furtwängler, EMI CHS 7 63045 2.

Photographs by Neil Libbert

Pär Lindskog as Siegmund, Orla Boylan as Sieglinde and Kathleen Broderick as Brünnhilde

Robert Hayward as Wotan and Kathleen Broderick as Brünnhilde

Return to:

Return to: