S & H Book Review

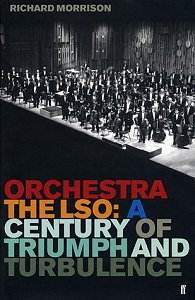

Orchestra,

The LSO: A Century of Triumph and Turbulence

by Richard Morrison, 306pp, Faber & Faber

(2004), £20 (MB)

Purchase from AmazonUK

AmazonUS

It is 30 years since the last biography of the LSO was published, Maurice Pearton’s The LSO at 70: A History of the Orchestra. At least this new book has a different title – and partly a different emphasis - and that suggests a story that is more human. Richard Morrison sees his task of being that of an oral historian – and it is refreshing that so many key players are interviewed, often in depth. Yet, books of this kind can be notoriously dull reads. Stephen J Pettitt’s biography of the Philharmonia Orchestra (apart from being dreadfully proofed) reads like a catalogue of concert dates (if anything, Morrison goes into reverse here with a lack of concert information). Maurice Pearton’s book is dry – but impeccably sourced, and rather less cynically opinionated than Morrison’s. Sir Thomas Beecham gets a raw deal at the hands of The Times' Chief Music Critic; for a more objective history Pearton offers a more factual analysis. Morrison’s biography avoids the shopping-list character of the first and takes, at its best, the factualisation of events and puts them into a narrative that, if not conventionally chronological, never ensures the reader gets lost.The chief interest of Morrison’s book, however, is the 30 years that Pearton did not cover, and in this respect Morrison is exemplary. Sat as a chronicler of events – and a contemporaneous chronicler at that since the writer has covered these years as a music critic – the very subtitle of the book – ‘Triumph and Turbulence’ – seems almost written for this period. The – almost – ruinous exodus of the orchestra from the South Bank to the Barbican ("123 entrances and exits with no obvious main one") and Claudio Abbado’s financially disastrous first festival devoted to music from the Second Viennese School in the 1980s ensured the orchestra teetered on the precipice of bankruptcy. The orchestra’s rescue was almost humiliatingly conceived – pop concerts, soundtracks, virtually anything to rake in the money to clear its deficit. When the Art’s Council agreed to continue funding the orchestra on the condition it reversed its deficit within three years it was done on the basis that the orchestra would fail to do so and thus neatly solve that decade-old conundrum of compacting London’s ‘Big Four’ into a ‘Big Three" (still, of course, unresolved).

The triumph is surely Clive Gillinson’s - and Morrison makes little attempt to hide this view. A revolutionary orchestra manager – plucked from the ranks of the LSO ‘cellos to run the orchestra on the basis that he had owned an antique shop and therefore knew how to read accounts – he took on the job without actually knowing what the crisis was. He cleared the deficit in two years – and took the risk in 1985 of mounting Claudio Abbado’s costly – but highly successful - ‘Mahler, Vienna and the Twentieth Century’ festival. Heralding a new format for LSO concert going, it is one that proved evolutionary, continuing almost annually by the orchestra under conductors such as Pierre Boulez, Mstislav Rostropovich and Sir Colin Davis. But Gillinson’s genius – now copied from New York to Berlin – was to make the LSO more than just an orchestra. It’s outreach projects – culminating last year in St Luke’s – are models of their kind, though it is arguable that the orchestra’s commitment to the ‘community’ is less wide-ranging than that of, say, the Philharmonia. The latter spends almost half its time playing outside London; that cannot be said of the LSO. The founding of LSO Live has still to be emulated successfully elsewhere, and whilst not all the discs released so far have been critical successes many have. It’s recent Lincoln Center residency offers it an outpost in the States that Gillinson initiated when he first became Managing Director in creating the LSO Foundation. Whilst Morrison doesn’t explicitly say it, one gets the feeling that he believes the LSO to be most modernly run of orchestras.

Things were not always that way, of course. Today, any conductor would accept an offer to conduct the orchestra; thirty, even twenty, years ago the orchestra went out of its way to alienate conductors. Giulini and Jochum both refused to return because they had been so badly treated. A recording session with Simon Rattle went badly wrong and Rattle is quoted as saying that he’d "never conduct the LSO again". It took Gillinson thirteen years to persuade Rattle to come back – and when he did he gave memorable performances of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (even hurling his baton into the ‘cellos during the final minutes of the first movement) and Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos. Morrison believes Antonio Pappano to be Colin Davis’ natural successor; it would surprise few people if it were Simon Rattle instead.

Morrison can tend towards the uncritical and dismissive at times. For example, he allows only a page and a half to discuss the conductor Sergiu Celibidache who made such an impact on the orchestra. Performances by that firebrand could arguably be defined as some of the orchestra’s greatest in this period – a Schumann Second, for example – yet Morrison confines himself to merely writing about the intensive rehearsals and the fact that half the orchestra loved working for him and the other half detested it. Similarly, could a little bit of protectionism (Morrison is, first and foremost, a music critic) be rearing its head when he refuses to divulge the name of the critic who dared to criticise Carlos Kleiber’s concert with the LSO, a review that ensured that Kleiber never conducted in London again? (An error in the indexing also makes the assumption that Erich and Carlos are one and the same, laziness on the part of Morrison who refers to Erich as just ‘Kleiber’).

One of the weaknesses of the book is an occasional tendency towards the prosaic. At times the lack of discursiveness hardly measures on the barometer of critical opinion; too often it is merely narrative interspersed with first hand remembrance. Claudio Addado, for example, seems to come in for a lot of (perhaps justifiable) criticism – he was, for example, simply uninterested in the financial side of the orchestra (perhaps a reason why he left Berlin at a time of similar turbulence in that orchestra’s recent history). LSO players talk of the incandescent live performances that persuaded them to appoint him in place of Previn (at eleven years the longest Principal Conductor in the orchestra’s history – and also the one with the "worst stick technique of any conductor") but there is nothing overtly constructive about why Abbado proved so problematical. Rehearsals were apparently dull – Abbado is described as being "disorganised" – but the performances were invariably profound.

It is often up to musicians to offer the insights, rather than the author. Colin Davis, for example, talks broadly about the orchestra’s sound, much of which he believes is down to its late admission of women into its ranks (the LSO being the last in Britain to admit them). He is surely right to compare the warmth of its string tone today with the harshness of sound generated by conductors like Solti and Dorati – a recording by the latter he describes as "…very hard, not seductive". Solti’s Mahler with the LSO – notably his superbly played recording of Mahler’s First - an LSO speciality – displays similar traits.

Yet, despite these minor failings in the book what does come across is the humanity the writer so ably captures. Morrison clearly sees the LSO as a collective of individuals – its charter almost necessitates this – but it is the human stories – the triumphs and the weaknesses – that gives it such pace. One could not possibly read this book without smiling at some of the more outrageous tales – almost always, it seems, drink related. Previn recounts – in his typical style - an hilarious tale of alcoholic woe that saw one player reduced to a state of catatonia only hours before a concert. In another, the orchestra were barred form a hotel in Mexico – though in this case the LSO were not to blame (only weeks before the Philharmonia had "trashed" the place). A fascinating story about Svetlanov recalls a recording session during which the conductor consumed a large number of bottles of wine. Having told him they’d not give him a contract if he continued drinking the conductor stopped – only for the orchestra to realise that his performances became boring when he was sober.

Unlike Pearton’s book Morrison’s appears at a most propitious time for the London Symphony Orchestra as it celebrates its centenary year. Clive Gillinson has resurrected its finances to a state that most British orchestras can only envy (the shrewdness he displayed at one of the orchestra’s blackest moments in asking the Corporation of London to match pound-for-pound the orchestra’s Arts Council funding is rightly praised by Morrison). Artistically, its programming is unrivalled – certainly in Britain and definitely in comparison with the United States. In terms of its playing the orchestra has probably never sounded better than it does today. For that, Sir Colin Davis is to be thanked; he has not just brought a glowing sheen to the orchestra’s sound but a technique that has no equals. On most days, the LSO outplays any orchestra anywhere.

Richard Morrison’s biography – one of the most successful yet done of an orchestra, though by no means being the most authoritative on its subject – is largely balanced and thought provoking and a worthy companion for an orchestra at the peak of its considerable artistic power. It is a work of integrity, well illustrated and remarkably free of both factual and editorial errors. I can’t imagine anyone being anything other than delighted with it.

Marc Bridle

Return to:

Return to: