S & H International Concert Review

Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor ("Resurrection"), Christiane Oelze (sop), Monica Groop (mezzo), Los Angeles Master Chorale, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, California, October 30 and 31, 2003 (BH)

|

; ; |

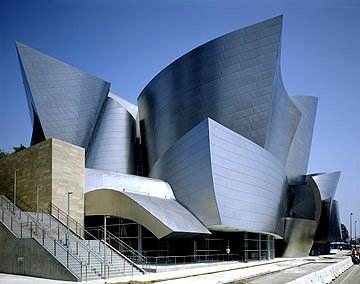

Perhaps it is fitting that in a city consumed by cinema, the sound in the new Walt Disney Concert Hall has a gripping, Technicolor immediacy, as if the seats were positioned directly in front of an enormous panoramic screen. Frank Gehry and the brilliant acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota have given us a space with an almost palpable, tangible "feel" to the sonic picture that is extremely pleasurable. I donít think itís too early to say that Los Angeles now has one of the best places in the world in which to hear classical music. (For reference, my favorite hall is the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, with Carnegie in New York a very close second.) As a New Yorker, itís making me a bit envious.

With contemporary musicians more accustomed to its demands, Mahlerís sprawling Second Symphony has become almost as ubiquitous as Beethovenís Ninth, but the former is perhaps even better for testing a hallís acoustics. On every page, the score requires the massive ensemble to zigzag between earthshaking barrages of sound and treacherously exposed solos for all instruments. Like much of Mahler, this piece works an orchestra pretty hard.

Salonen launched into the first movement with tempi on the swift, hell-bent side, opting for brazen ferocity, with tense, angry strings anchored by the double basses rearing up like wild horses. The hallís uncanny clarity seemed a boon to the musicians, as their gifted conductor seemed to revel in urging them past the generally advisable speed limit, and if I had access to Gehryís shiny new sports car, Iíd probably want to take it for a spin, too. Salonen and this orchestra must be thrilled, and it absolutely came across in the caliber of their playing. About halfway through, the orchestra romped through a furious, devastating march that then wound down, before suddenly rising up again like a dragon with dramatic, decisive unison octaves, followed by silence. Miraculously, as the resonance from the final brutal punch hung in the air, the hall was silent. The audience hardly breathed, as if even the sound of an exhalation would break the mood. (Given the vivid feedback in the room, a particularly loud breath might indeed be audible throughout the house. If someone drops a coin on the balcony floor, everyone will know about it.)

Here, and generally all night, the brass were splendid, with confident intonation and often anchoring the entire ensemble. The sardonic middle movement (St. Anthonyís sermon to the fishes) glistened with the woodwinds rippling through its graceful, bubbling textures, and the hall enabling audibility of every single strand. The oboe and clarinet passages almost made me chuckle out loud, as did the clacking of the sparingly used wooden blocks.

As Monica Groop stood up to begin the "Urlicht," the audience again became completely still, anticipating her entrance. She seemed completely calm as her mellow voice poured out and enveloped the space, and I became lost in blissful contemplation. The movement only lasts about five minutes, but in the right hands seems timeless.

In the opening of the final movement, Salonen probably caught some unwary listeners by surprise with a huge thunderclap ricocheting off the warm wooden walls. In the pages that followed, many instrumental lines were audible that are sometimes slightly obscured in other venues. The offstage effects, such as the interruption by a distant marching band, were carefully gauged to be just loud enough, while maintaining a dreamlike, faraway quality. Eventually the radiant Christiane Oelze joined in effortlessly, her high notes easily sailing above but not overpowering the blend, and the Los Angeles Master Chorale, immaculately prepared by Grant Gershon, sounded glorious in Gehryís dramatic space. If they did not quite produce that transcendental "hush" in their initial entrance, I quickly forgot about it while basking in their refined approach, disciplined diction and elegant sound. Again the effect was almost visual, as if everyone had collaborated on an enormous painting that rose up and hovered in the air in front of us.

In the final spectacular minutes, the orchestraís outstanding organist, Joanne Pearce Martin, seemed to relish her chance to at last leap into the mix, and she sounded superb even using an electronic organ. (Technicians are putting the finishing touches on the striking centerpiece designed by Gehry and Los Angeles organ designer Manuel Rosales. The 6,125-pipe instrument is already making listeners salivate and will be ready next year.) As the chorus ascended to the inexorable rapture of the closing pages, Salonen expertly terraced the approach, making the most of the workís overwhelming conclusion.

I heard two performances, on Thursday and Friday nights, sitting first in the middle of the Terrace level above, and then on the side overlooking the orchestra, which provided a different but equally vivid perspective. As an analogy, imagine a cube made of three layers of transparent plastic: clear, yellow and blue. When viewed from the front, the colors combine to appear green, but from the side, the separate bands of color are visible. The side section offered this kind of auditory equivalent, with each instrumental section clearly defined. I closed my eyes and enjoyed being able to clearly pinpoint the massed strings at left, woodwinds and brass in the middle, and percussion on the right. Granted, this is probably not always an ideal soundstage, but I found it had an immediacy and thrust that were thrilling. It must be said that there seem to be few bad seats anywhere in the place.

On Thursday night, the orchestra played almost flawlessly, with some of the most gleaming trumpet playing Iíve ever heard. Principal Donald Green received several well-deserved ovations at the close. And those trombones and horns! If Friday night was not quite as pristine, perhaps Salonen had urged the players to cut loose a little more, and the payoff was a performance with even greater passion, even more broadly emotional. Throughout, Salonen seemed to encourage extremes in volume -- lower lows and higher highs -- as if exulting in testing the new laboratory.

Perhaps recognizing the sense of occasion, the L.A. audience was exemplary, whether mesmerized by Salonenís electricity or the new venue, or both. A live concert invariably incurs stray noises, but these performances had many fewer than most.

After the initial reaction subsides to Gehryís supernova of a building, it will be interesting to see how the sound is perceived in the wake of these opening weeks. The allure of the space is so seductive that it is hard to resist transferring the visual excitement to what your ears are hearing. More than with many halls, the breathtaking flood of curving lines and planes seems to invite you in, somehow subtly preparing your brain to receive music. It didnít hurt to recall, for a moment, Disneyís 1940ís classic Fantasia, a film that, despite some kitsch and the editing in the music, nevertheless jump-started many young classical music lovers. He would probably be delighted at the prospect that this modern, sculptural marvel will radically change the Los Angeles musical scene.

Bruce Hodges

|

|

Return to:

Return to: