S & H Interview

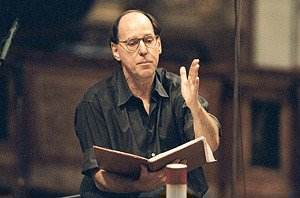

Gilbert Kaplan talks to Marc Bridle about Mahlerís Second Symphony.

In this brief interview, the conductor Gilbert Kaplan talks to Marc Bridle about his forthcoming performance of Mahlerís Resurrection Symphony with the Philharmonia Orchestra and his new recording of the work with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

MB: How would you describe your relationship to Mahlerís Second Symphony?

GC: Well, I have thought about this a lot and the only way to describe it is as the equivalent of a love affair. I first encountered this music when I was 25 and it kind of wrapped its arms around me and never let go. Itís a love affair my wife tolerates.

MB: How has your view of the symphony changed over the years?

GC: One of the big issues with this symphony is its title which is called Resurrection. I have never myself embraced the notion of life after death and therefore the programmatic aspects of this work have evolved over the years. A great awakening came when I conducted the first performance of the symphony in China, which they had never heard before, and I discovered that the Chinese word for resurrection is in fact equivalent to self-renewal. So for those that canít embrace the notion of life after death, as I canít, the symphony can still have great meaning beyond the musical meaning of self renewal, rebirth during your own lifetime, and recommitment to everything that is important. And I find that that affects the way that I conduct the end of the symphony - this big glorious chorus which can be taken very seriously, though I think very exhilaratingly, and thatís affected by my view of the work as a whole.

MB: Do you find orchestras have pre-conceived ideas as to how they think the symphony should be played and how do you persuade them to accept your own views of the work?

GC: Orchestras are of course captive of the conductor, so when I come to an orchestra I am likely to want to hear a first rehearsal to hear how they played it the last time. Now, Mahler is such a brilliant orchestrator, and so interested in detail, that he never really trusted conductors. He writes in so much of the score what you should do, even writes what you should not do, he writes Ďdonít slow down hereí Ė how did he know you were going to slow down there? Ė but ultimately you have to convince the orchestra, not only by your authority, but also by your musical ideas, and mine are very personal. I am probably credited with coming as close as possible to following these thousands of directions that Mahler has put in the score but Mahler said that in every performance a work must be reborn and you must bring your own light and your own experience to that. Itís a highly personal thing for me and I think that orchestras feel that and they come with me. Iíve never yet had an experience with an orchestra not embracing my view of the piece.

MB: What, in your view, are the significant differences between the new performing version and existing versions of the score?

GC: These are late changes that Mahler made, and there are hundreds of them, but why they didnít get in the score I donít know. For some people the differences will not be audible, but these are a matter of life and death to Mahler - you are not going to hear the trumpet play something that the bassoon used to play. But every time Mahler conducted it he would go back to a master score and enter corrections and find new colours. Mahler, more than any composer, in my view at least, was capable of expressing feelings in music Ė it is the reason people cry at concerts, not because they are sad Ė and Mahler gets under your skin and touches those moments in your life which brings you back into contact with them. This happens because of those details in the score and those changes he made were just tweaking it one more notch. Iím sure youíve had the same feeling with your own writing Ė just as everyone must have in journalism Ė in trying to find the right adjective when another one would have worked. The reader may not know the difference but the writer does.

MB: Some writers believe that the Wiener Philharmoniker has an ambivalent approach towards Mahler. Do you accept this?

GC: Well, Iíve heard this view expressed also and it is true to say that during Mahlerís time the orchestra was certainly less attentive towards his music than they ought to have been. But at the press conference announcing my new recording with the Vienna Philharmonic the head of the orchestra stood up and said they loved the experience of working on the new score for many reasons, one of which was that they had a bad conscience about not having a played a single premiere of Mahlerís music when he was in Vienna. And so he said, ĎToday we have finally played a premiereí, because this recording of Mahlerís Second is probably the first time we are hearing the score the way Mahler really wrote it with all the changes put in. I also think that view exists because Mahler was much less played in Vienna, but not nearly as much as some critics say. If you look at the facts they have played Mahler quite a bit and, they are Viennese, and have that wonderful style of the sliding strings and seem uniquely able to get the music to dance so beautifully. I donít think I have ever conducted an orchestra that was more in tune with whatís in the score. They needed less direction because they just instinctively played it. So whether they like it or not, in the old days I donít know, but today they just love it.

MB: What did you learn from conducting this work with the Wiener Philharmoniker?

GC: Well, I learnt how much an orchestra can do without a conductor. There are certain things which if you let an individual musician play naturally, and if you donít get in their way, magical things happen. There are plenty of moments when Iíd like to believe that without a conductor chaos will happen and there wouldnít even be a clear point of view. In the second movement, for example, where thereís just the dancing Ė an Austrian Ländler Ė and you donít need to do much. You just set the tempo and let them play the music as they know best. In the dramatic moments, the marches, the power, the contradiction of feelings, thatís very much set by the conductor, and particularly when it gets very personal. You do bring your own life to this, but for some things this orchestra doesnít need any conducting.

MB: Your concert performance with the Philharmonia is not of the new edition. Why is this?

GC: Mainly because the new edition is not yet published. The recording with the Vienna Philharmonic was made by entering about 500 corrections into their parts, and itís the feeling of the publisher of the new score Ė which is the Universal Edition, Mahlerís traditional publisher, and my foundation as co-publisher Ė that the first live performance would be with the printed parts. I have changed in the parts of the Philharmonia all of the very significant changes, correcting all the wrong notes, for example, moving the notes which were written for one instrument to another. But some of the fine points are things that I do any how, that come instinctively to me, mainly from knowing the music, so while it will not be officially the first performance of the new edition it will have the essentials of that new edition.

MB: The RFH has a notorious acoustic for big works like Mahlerís Second. What will you be doing to ensure that the clarity of the choral writing particularly emerges as it should?

GC: Iíve conducted in the Festival Hall before Ė twice Ė so I know this hall and I know the problems you are referring to. Youíll really have to come and observe how I deal with it because it is difficult to describe in non-technical ways as to what one does to overcome a certain lack of reverberance. But I must say that the RFHís acoustics are not really as troublesome as people make them out to be. It seems fashionable to say that the acoustics for the Festival Hall are appalling Ė and perhaps for some works they are Ė but I can say - and I should disclose my interest in this because I am a member of the board of governors of the South Bank Centre Ė that of course it wonít sound like a performance from the Musikverein or Carnegie Hall Ė at least not yet. We are planning on restoring the acoustics to a very high level over the next few years Ė but as for now, a work like Mahlerís Second will survive the hall very nicely because it does fill the sound. Weíll have a vast chorus there on Tuesday night Ė over 240 voices Ė a great orchestra, with whom Iíve played the work five times, so there should be no excuses at all.

MB: Are there any conductors, recordings or concert performances of the work that stand out in your mind as having been extraordinarily insightful experiences?

GC: Well, of course, the first one I heard was of Leopold Stokowski and the American Symphony at Carnegie Hall, which points out another interesting phenomenon. I heard a tape of that performance some years ago and I was not as impressed with it as I was when I heard it live. And that goes to show that we speak so much about performance and not enough about music. You can imagine someone hearing a first performance of Beethovenís Ninth Symphony Ė not played especially well Ė and theyíd be overwhelmed by the music because they wouldnít be able to compare it to one thing or another. Having said that Ė Iíd prefer not to comment on individual conductors because most of them are my friends these days, even the dead ones Ė but I do think that Britain had a wonderful succession of great Mahler conductors. Iíll mention only two Ė Klaus Tennstedt was one of the foremost and I learned a lot from watching him and Jascha Horenstein, perhaps not that well known because he never had his own orchestra. But his recordings Ė and especially that of Mahlerís Third, which I think is the foremost recording of the work Ė if that doesnít put me in trouble with some of my other conductor friends Ė are simply outstanding. I learnt a lot from Leonard Bernstein who pointed out to me that the real hero of this music is Mahler and not the conductor and that if you really look into the score youíll find these magical things that no conductor could ever really improve upon and yet there are so many conductors who donít have enough time to study the score so they miss some of these things. You canít get a good performance by simply following the technical side of the score, but you canít get a great one if you donít.

MB: What future plans do you have for Mahlerís Second?

GC: I try not to conduct more than three or four times a year. I always want it to be fresh, with a different orchestra and a different chorus so my next concerts will be in Washington DC with the National Symphony Orchestra in the Spring and, then, later that Spring in Moscow. Iíve conducted about five times in Russia, a few times in Moscow, but itís always exciting and I try to learn the language before I go so I can actually communicate with the musicians. And my Russian has become pretty good. I havenít done one with the Berlin Philharmonic yet and I suppose Iím unlikely to for the time being as Simon Rattle is the conductor there and does this piece extremely well, and likes to conduct it. Iíd be surprised if heíd let a guest do it.

Gilbert Kaplan conducts the Philharmonia Orchestra on 4th November at the Royal Festival Hall. His new recording of the world premiere recording of the new edition with the Wiener Philharmoniker is released in the UK on 4th November on Deutsche Grammophon.

Pictures: © Tanja Niemann/DG & Adrian Bradshaw/DG

Return to:

Return to: