S & H Opera Review

Verdi’s Aida at the Royal Opera, 28th November 2003 (BK)

The Royal Opera’s new Aida (a co-production with the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels) was expected to cause a stir because of Robert Wilson’s direction and set designs. Well -known (or notorious, depending on your point of view) for his rejection of either realism or psychological approaches in his productions, Wilson is also famous for gnomic utterances from time to time. He has variously said, ‘Opera isn’t just music – it’s architecture and light,’ ‘Opera is usually totally subservient to the words… but there’s music, gesture, light, sets…,’ and ‘All opera is dance.’ Right on there, Bob baby. Gotcha! Yup! Well, maybe.

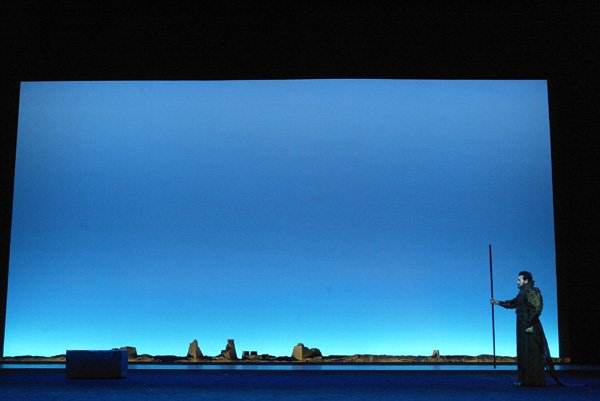

What you get in a Wilson production (of which there have been many, from Glass’s Einstein On The Beach onwards to The Temptation Of St. Anthony at Sadler’s Wells in September) is minimalism on the grand (oh, well) scale. Sets are spartan, there’s an abundance of lighting (of which more later) and performers process slowly round the stage using stiff and stylised hand movements – all of which upsets some divas so much that they walk away huffily as rehearsals begin. It’s a Noh or Kabuki approach to opera, as Wilson himself acknowledges, in which familiar expressions of emotion are essentially absent. No one touches anyone, ever; not even Aida and Radamès in this production.

But perhaps there’s a point to this. Scale model sphinxes, pyramids and Nefertiti look-alikes are clearly not essential to Aida any more than horned helmets are necessary to Valkyries. Wilson’s dictum (or at least one of his dicta) is that what we see in opera affects what we hear, and often adversely at that. And if perception can be blunted by opulent sets and heavy symbolism in opera production (a reasonable proposition on occasion) the question of how best to avoid this remains. Which is where Wilson’s lighting comes in, even though he said recently that he’ll drop dead if one critic writes about the quality and value of the light. Sorry Bob.

The lighting is just wonderful. It is beautiful to look at for its own sake, but more importantly it creates from the outset a proper sense of mythical setting which dispenses completely with the need for more ‘realistic’ scenery. This sense is sustained throughout the whole production, ending with an entombment scene in which almost the only illumination is provided by spotlights focussed on the hands and faces of Radamès and Aida. Altogether splendid then, and sufficient in itself: certainly without the need for some of the more curious costume designs provided by Jacques Reynaud.

While some earlier reviews reported the music as lacklustre, there was a real sense of measured brilliance in terms of pace, drama and clarity from Antonio Pappano, from his orchestra and from the chorus (especially fine in the unaccompanied passages) on this occasion. Of the soloists, both Johan Botha as Radamès and Ildiko Komlosi as Amneris sang with delicacy when needed but also with substantial power on demand. Both were excellent. Norma Fantini (Aida) was somewhat weaker than either of these, but achieved a rewarding degree of emotional expressiveness in the final scene and was always completely musical. Mark S Doss as Amonasro failed to impress however.

Insofar as there was a trick to getting to the heart of this production, it was to realise early on that attempts to find meaning in its symbolism‚ were fruitless and to give them up. In that sense, just looking, opening the ears and ceasing to worry about why Radamès was dressed as a Samurai or why the Priests of the Temple of Vulcan had come as Romulans (it’s a terrible thing, the Unconscious) was the only solution. It's probably a Zen thing. Right, Bob?

Bill Kenny

PHOTO CREDIT: CLIVE BARDA

Aida - Verdi

King of Egypt - Graeme Broadent

Amneris - Ildiko Komlosi

Aida - Norma Fantini

Radames - Johan Botha

Ramfis - Carlo Colombara

Amonasro - Mark S Doss

Messenger - James Edwards

High Priestess - Victoria NavaConductor - Antonio Pappano

Director, sets and lighting - Robert Wilson

Costumes - Jacques Reynaud

Choreography - Makram Hamdan

Return to:

Return to: