S & H Concert Review

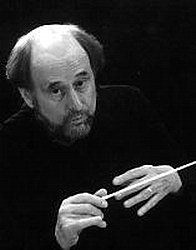

Beethoven, Missa Solemnis, Philharmonia Chorus & Orchestra, Sir Roger Norrington, RFH, 5th March 2003 (AR)

Melanie Diener - soprano

Cornelia Kallisch - mezzo-soprano

Peter Bronder - tenor

Alfred Reiter - bass

Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis is one of the most enigmatic works in the classical canon and one of the most difficult to conduct. Akin to Verdi’s hybrid Requiem, Beethoven’s Mass in D goes beyond being merely a sacred work but incorporates elements of the secular operatic, dramatic and symphonic forms.In my view, Klemperer and Toscannini are the only conductors who have ever got to the emotional and structural core of this masterpiece; it takes genius of great stature to reveal and combine the complexities of feeling and dynamics of force in order to realise this work as an extra-musical experience.

That said, Sir Roger Norrington’s interpretation of the ‘Missa’ was revelatory in his seemingly fresh and direct approach, stripping away the cobwebs of heavy romanticism, and cleansing the score of sensational mannerisms and congested orchestral textures that tend to bedevil this work. Norrington got the strings to sound like an anti-vibrato, quasi-period instrument orchestra, and this emphasis on an ‘authenticist’ string tone produced great transparency – albeit sacrificing somewhat the weight and depth essential to the work.

This was the main criticism of the conductor’s ‘period’ approach: indeed, what was lacking throughout this performance was the pulsating base-line normally provided by the double-basses and ‘cellos, essential to the grainy darkness this dramatic work demands. (Harnoncourt’s quasi-period reading of the ‘Missa’ also has this problem of weak basses and ‘cellos.)

The Kyrie was conducted and played with incisive clarity and a bold directness incorporating angular, cutting playing, as if they were trying to slice to the bone of the score. Norrington and his players turned up the heat in the Gloria which was taut and tough, with crisp playing from the Philharmonia brass which introduced a punctuating sound to the closing passages.

In the prelude before the Benedictus, scored for just strings and woodwind, the Philharmonia’s solemn sound enhanced the melancholic mood of the music; here Norrington achieved a sense of meditative reflection without letting the music drag or devolve into mere sentimentality. Unfortunately, Concert Master James Clark’s seemingly eternal solo violin seemed scrawny and out of place, sounding like a lost soul.

The most dramatic moment of the evening was the final Agnus Dei, where the conductor articulated jagged, thrusting rhythms and the Philharmonia assumed an eerie, almost sinister tone. The threatening military fanfares for trumpets and drums had a salutary directness with Andrew Smith changing to ‘hard sticks’ with great effect, and Norrington heightened the drama to a pitch of awesome intensity

Having the four soloists placed directly behind the woodwind section paid dividends: in the lyrical passages particularly, their voices blended beautifully with the sensitive and warm tone of the instruments. Notably refined and stylish was the tenor Peter Bronder. The four soloists were integrated into the chorus, rather than being ‘star’ performers. Their voices blended beautifully with the Philharmonia Chorus stationed immediately behind them. The chorus was on top form, although on occasion they came close to sounding almost unrestrained, perhaps due to Norrington’s melodramatic and expressive gestures urging them to ever-greater efforts. Sometimes they threatened almost to burst the RFH at its seams.

The applause seemed almost subdued, as if the audience were stunned after such a magnetic and awe inspiring performance; it was only when Norrington returned to the stage and selected soloists for special praise that the patrons began to cheer; and Andrew Smith got well-deserved ‘bravos’ in his turn. Indeed, Smith could have been voted Man of the Match for his mastery and understanding of the contribution to be made by the timpani in Beethoven’s magisterial score. My main criticism is that a quasi ‘period’ or ‘authenticist’ approach does not work for weighty scores like Beethoven’s ‘Missa’ (or Brahms German Requiem for that matter): these large-scale dramatic scores ideally require a deeper and fuller-bodied string tone.

Alex Russell

Return to:

Return to: