S&H Opera review

OPERAS IN BERLIN CHERUBINI Médée MOZART The Marriage of Figaro, Die Zauberflöte & Die Entführung aus dem Serail May/June 2002 (PGW)

CHERUBINI Médée Deutsche Oper Berlin 1 June 2002

Cherubini's historically important opera, a favourite Callas vehicle, is being given now at Berlin's Deutsche Oper in the original French version of 1897, with a great deal of spoken dialogue. The staging and production by Ursel & Karl-Ernst Hermann is effective in concentrating the action in vivid images placed in a deep triangle with black walls, which help to focus the sound and open up occasionally to suggest the sea beyond. Iano Tamar is powerful in suggesting the torments of Medea, sorceress and rejected wife, trying to contain her vengeful urges towards the man whom she had, with her magic, raised to power, betraying her father and killing her own brother on the way to pave the realisation of his ambitions; an anti-hero & anti-heroine pair even more repugnant than the Macbeths? Dressed mainly in reds, at the denouement glittering as if drenched in blood, Iano Tamar's singing is commanding, beautiful and rock-steady through the registers, rising to a great climax in the extended scene which culminates in the murder of her little boys and even then enlists some sympathy from the audience.A real star, who should be a magnificent Leonora and Wagnerian soprano.The Jason (Donald Kaasch) was implacable in insisting that his sons' future should be within Creon's court and was solid but unsympathetic in his dialogues with Médée. Most persuasive and involving for us was the in depth characterisation and direction of the ill-fated bride, Victoria Louklanetz as Creon's daughter, the Princess Dircé, an edgy, even appropriately shrill soprano (this is not written pejoratively) whose uncertainty was depicted in her scenes being dressed for the wedding, smothered in yards of white more as if being bound in a winding sheet, tottering towards her fate along the ritual path of the table top for a wedding feast which was interrupted by the arrival of the wife that was. Those images, and her representation of vulnerability, will be long remembered.

The music was forcefully projected by the fine Deutsche Oper Berlin chorus and orchestra under Gabriele Ferro. How to characterise Cherubini's score, important in its time and influential in the development of dramatic opera? Perhaps in the same bracket as had been said about Saint-Saëns, once described as 'the greatest composer who was not a genius'?

* * * * *

MOZART The Marriage Of Figaro Staatsoper Unter der Linden 2 June Die Zauberflöte & Die Entführung aus dem Serail Komischen Oper 31 May & 4 June 2002

The Marriage of Figaro was seen in a rather disturbing and disorienting revival of a 1999 Thomas Langhoff production, with a model theatre on stage during the second half to remind us that it is all only theatre. Everything seemed run down and the first Act set seemed so rickety that we feared for the safety of the performers; was that telling us about the Almaviva domain or something about the Staatsoper itself? After the interval a huge space served for the Count's ceremonial courtroom, chapel and garden (confessionals doubling as pavilions). A high bridge across the stage gave a new slant to the conversations overheard and deliberate confusions. Of several (? deliberate) stage gaffes, the most disconcerting (given the current practise of staging visual counterpoints to opera overtures) was that the curtain didn't go up until Figaro had finished measuring up the 'so convenient' marital bedroom! If these oddities were all meant as humour, some of it was of a heavy type and, all in all, there was little of the fun or the heart-warming moments of genuine sentiment one expects also in a Marriage of Figaro (see the DVD from Zurich Opera, in which the Act 3 recognition sextet could bring tears to your eyes, TDK DV-OPNDF).

There was however plenty of ingenious detail to enjoy. The first act hidings around the chair were expertly managed and the androgynous Patricia Risley particularly well characterised as Cherubino, a convincing adolescent boy in modern dress, gawky dressed as a girl who would deceive nobody, his unruly locks shorn to make him a proper young soldier. Katherine Kammerloher and Stephan Rugamer acted and sang well as the late marriers; each had striking voices and should not have been deprived of their arias, especially for our 6 o'clock Sunday performance - no worries about last buses (q.v. my letter in The Times 10 June about Berlin transport)!

The leading women were less memorable, Dorothea Roschmann small voiced and a diffident actress, but giving a beautiful Deh Vieni, Regina Schorg's vibrato playing havoc with line in the Countess's arias. A substitute Count, Klaus Häger, filled his role well, replacing Roman Trekel. After two performances in May, the Swiss conductor Phillipe Jordan had taken over the orchestra (a little rough in the overture, during which there were no visual distractions) from the company's musical director, Daniel Barenboim.

The undoubted star of the show was Kwangchul Youn, Marcellina and Bartolo's unlikely-looking son, as Figaro, a company singer who has been featured in smallish parts and was the original Bartolo in 1999. Frustratingly, in Berlin we were not provided with any biographical notes about the singers (not to speak of the over-inclusive CVs usual in UK) so we did not know if this was his debut in the part? With a strong, authoritative presence and a huge, well-focused baritone full of character, he would appear destined for the international operatic stage.

We learnt the next day that the Staatsoper has suffered 'technical problems' more often than is acceptable, which seems to be the more likely explanation for some of the peculiarities that bothered us.

* * * * *

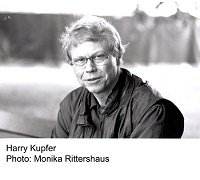

The great director Harry Kupfer (see the newly released TDK DVD of his famous production of Die Soldaten) is retiring from the Komischen Oper after 21 years, during which he has been responsible for 38 productions, nine of them still in the repertoire. It was serendipitous that two on show were his affectionate realisations of Mozart's German operas. It is believed that without Kupfer's contribution the Komischen Oper might not have survived the upheavals in Berlin's cultural world following unification, and the financial crises that continue to beset the capital.

Harry Kupfer's stage direction of Die Zauberflöte and Nicholas Kok's pacing of the music emphasised the pantomimic qualities of this popular entertainment, which carried the sublimities of Mozart's genius lightly. To its advantage, the clear and sharp, but not cold, acoustics of East Berlin's moderate sized opera house helped the cast to get across their words easily, so that everyone was involved. The old story seemed to be largely taking place in Tamino's dream and came up again fresh as ever, with a fine mixture of periods in the costumes and staging from not-too solemn ritual to robot-driven computer graphics, took in its stride the incongruities of the tale. At the end Tamino froze in a final tableau, unable to join his Pamina to ride away on her splendid white unicorn, which the three winged boys had been stroking with solicitude.Years ago I saw four ladies of the Queen of the Night rehearsing under Furtwängler at the Salzburg Festival, each hoping one of the others would be dumped; never before tonight had I seen Tamino attacked by three fearsome hungry dragons in the first scene! Why three? All was explained when the Three Ladies stepped out from them, and proceeded to dominate the first Act with personalised acting, and winning singing from each. The whole show was facilitated by three jockey-capped boys of our own time (hiding to pretend to be unseen), who acted as general factotums on stage. They threw out costumes from chests on stage, first a cloak for the modern-dressed Tamino, and made a ready identification for the schoolchildren who surrounded us, exemplary in their behaviour and entranced by all the goings on.

Visibility of the main action was helped by a small raised platform, and the elaborate scenic transformations were managed without any pauses, save for the generous applause which punctuated the proceedings throughout. The whole stage came into use for the populous, Freemason ceremonies, and scenes in which animals were soothed by Tamino's flute, and Monastosos's thugs of the East by Papageno's bells. Sarastro's community of devotees and the general population, dressed in a fine mixture of period and modern styles were taken by the 'choir soloists' of the company, a nice nomenclature recognising how chorus deployment has advanced in modern opera production. The main parts were all well taken (no names known to me) and sung by an accomplished cast; Romelia Lichtenstein had vocal difficulties in the Queen's taxing arias and the Three Boys were weak. On our night a computer bug halved the lovers' trials - the two robotic Armed Men (who had donated their singing parts to Sarastro and his Speaker!) failed to get the Ordeal by Fire up onto screen, though suitable computer graphics did appear to represent Water! The bright lighting was notably effective, often in front of dark backgrounds. All in all, a thoroughly effective and acceptable version of a perennial gift to imaginative opera directors which made a happy start to a week of opera in Berlin.

One of Harry Kupfer's earliest creations was Die Entführung in 1982, and we saw its performance No. 201. The production, with revolving sets by Marco Arturo Marelli and costumes by Reinhard Heinrich, is traditional and feels so right that there really is no call to change it. This proved to be the most completely satisfying of our four evenings of Berlin opera. Yakov Kreizberg produced the most refined orchestral playing, and he achieved perfect unanimity and flexibility from a well-matched team of principals. Acting and diction in this 'Deutsches Singspiel' were impeccable and projected without forcing or overdoing stage business, and it was a pleasure to share with the German speaking audience most of the jokes and the generous applause which punctuated the performance. It is an unusual piece, with a non-singing crucial character, the Pasha who holds everyone's fate in his hands.

Osmin & Blondchen Osmin & Pedrillo The two pairs of lovers are each soprano and tenor, and the only low voice is the bass Osmin, his sudden changes of mood well conveyed by Thomas Rühmann, who has the necessary agility and range.Clemens Bieber and Andreas Conrad were excellent as master and servant, and Tatjana Korovina bubbled over with excitement and affection as the bespectacled English girl. Most outstanding was the Konstanze, Marcela de Loa, a splendid singing-actress, with a creamy voice, never hard edged under pressure. She remained fully in character whilst expressing the conflicts of her predicament through her two demanding arias. A glorious evening, which for me re-established Die Entführung aus dem Serail in the pantheon of Mozartian masterpieces.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Entfuehrung aus dem Serail:

1. Blondchen: Tatjana Korovina (Blonde), Guenter Missenhardt (Osmin)

2. Andreas Conrad (Pedrillo), Guenter Missenhardt (Osmin)

Photographer: Arwid Lagenpusch3. Zauberfloete: Klaus Haeger (Papageno), Ilya Lewinsky (Tamino), from above Bettina Jensen (first dame), Christiane Oertel (second Dame), Caren van Oyen (third dame).

photographer: Monika Rittershaus

Return to:

Return to: