'You can ask me anything you want to - anything at all' was perhaps not exactly the response I had been expecting from the baritone Simon Keenlyside, well known for his distaste for journalistic hype and, dare one say it, with something of a reputation for being other than charming off the stage. Quite why it is that anyone should expect singers to be delightful when they step down from the platform or take off their make- up has always been a mystery to me, since singers are no different to the rest of us in that some are naturally warm and open, and others are naturally reserved, but Keenlyside proved very willing to talk about his career and to enthuse about mutual interests such as the wildlife around San Francisco and the poetry of John Clare. I think it was Dietrich Fischer - Dieskau who said that 'there are only two positions for a singer, on his feet or on his back,' which I take to mean that when not singing they should be resting and not talking, and there are indeed many who would do well to take his advice since much of what they say veers towards the fatuous. It is a joy to encounter someone like Keenlyside, who, in common with his contemporary John Mark Ainsley, has a sharp intellect and interests beyond the promotion of self.

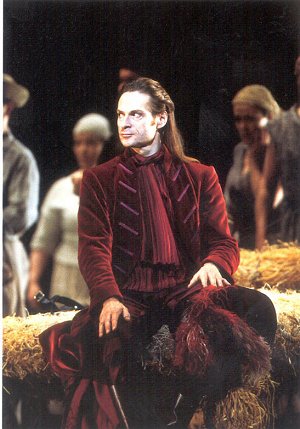

I had originally wanted to interview Keenlyside and Ainsley in connection with their singing of the roles of Don Giovanni and Don Ottavio in the Royal Opera's new production, since their assumption of those roles at this time provides an experience which as far as I know is unique - that is, both the Giovanni, singing his first one in this house, and the Ottavio, making his house debut, are both British singers, which in this very 'internationally' orientated house is quite remarkable. Critics were united in their praise for Keenlyside's Don, some of them going so far as to prefer his singing and assumption of the role to that of the 'first cast' Don, Bryn Terfel, with the 'Times' and 'Independent' respectively commenting that he revealed '..a voice on top form,' and that his acting was characterised by 'elegant understatement.'

I asked him about the role and the production; quite apart from getting very hot in the final scenes, it seemed to me that the staging presented quite a few challenges for Don Giovanni, but for him these do not loom as large as one might think, since 'The main challenge is always the role itself; it's aggressive, it has to be, and it's pretty brutal on the voice; I remember the great Thomas Allen saying that the challenge is really the balancing act you need to perform between putting enough into the character but not so much that you wreck your voice. Mozart's baritone roles are not consistently the vehicles for singing that others are, although of course they all have lyric bits in them, but the real demand is in driving the scenes forward - it needs a lot of theatre, which is true of everything, really!'

Part of his excellence in the role must come from his familiarity with Italian; he describes himself as having been 'enormously privileged' to have lived in Italy for six years, and indeed his Giovanni has more than satisfied even the Milan critics, Bottazzi even going so far as to say of his La Scala performance under Abbado, that 'It would be hard to imagine a better Giovanni.' He regards himself as 'a servant of the text,' and with experience has come the understanding that 'prima la voce' does not just mean standing and singing but conveying the words; he despises what he calls 'vocalise' and praises above all 'the natural, nuanced, unforced speaking voice, the real feeling, and it's just the same thing whether it's the 'Four Last Songs' or the poetry of John Clare. If you immerse yourself in what's on the page you can't go wrong.'

Keenlyside does not concern himself overmuch with the vagaries of avant - garde opera production - he seemed hardly aware of the furore caused by the last ENO 'Giovanni,' remarking that 'Mozart will survive all our fumblings; I don't advocate daft productions, and maybe nowadays the balance has shifted a bit too far. It's fair to say that in, say, the fifties it was too weighted towards singers, but now it's gone too far towards producers. But essentially, it really doesn't matter; only the other day I was watching an old film of Corelli and Bastianini singing in the silliest costumes and against the daftest set, but they sang sublimely and it worked! '

Most critics commented favourably upon the way the production had been re-worked between the first and second sets of performances, something with which Keenlyside was intimately involved; 'The most vital thing is that you are here, the audience is there and the voice has to get from a to b, and you need more than just fortes; Bryn has the most magnificent resources, he can do things thirty feet back behind an orchestra which I simply cannot begin to achieve, so the director had to be understanding in order to accommodate that - you have to use some give and take, and if I had to do some things with which I could have been happier, then I'm willing to live with that since Francesca (Zambello) was so perceptive in the way she made those changes.'

Mozart, he says, '.isn't polite, he's revolutionary, and everything is in the details, the nuances, that's where he hits you, not so much the arias as the recitatives and the not-so-major moments. There's that most wonderful part in 'Don Giovanni' where he invites all the peasants back and they all sing 'Viva la Liberta,' which has always struck me as pretty daring, just before the revolution; of course, Mozart would have got round his patrons by making all that seem related to the character being a libertine, but that's not it at all. In one performance I found myself whistling the 'Marseillaise,' managed to lose the tonality and came in on the wrong note, and I later realised that that moment is not unique; Papageno's aria 'Ein Madchen oder Weibchen' is so closely related to the 'Marseillaise' in musical terms, and it can't be coincidental that that aria is about freedom, and is given to the one character who wants nothing to do with the established order as represented by the Freemasons - isn't that fascinating?'

Papageno is of course one of the roles for which he is most widely respected, although he balked at calling it a favourite; 'I don't really care about roles, it's the pieces themselves that matter; I do adore 'The Magic Flute' and come out of it feeling wonderful - there are so many great moments, like the meeting of Tamino and Pamina at 'O welch' ein Gluck,' after all the maelstrom of the plot before then - that one sublime phrase, that calm in the storm, is part of what makes it, for me..'

He acknowledges that while most of the great Mozart roles are 'for life, since fortunately, for men, anyway, there are no real age limits defining when you can or can't appear in them, but there are so many other great roles such as Pelleas and Billy Budd which you have to seize with both hands if you are offered them, since they need doing whilst you are still fairly youthful! ' Keenlyside has been warmly praised for his Pelleas, and he obviously has a special feeling for Debussy's opera; 'It's all about shadows and nuance, and one has to get these - it's the intimate nature of the commentary between orchestra and voices, all those multi - faceted laminates of conversation and implication, and if you don't get these, then you're lost since there are no arias, as such. I would love to do it in a small room, because it's so delicate a piece, it's like trying to hold a spider's web in your hands. I can see why some people might not take to it, but that doesn't bother me; I don't understand anything, really, myself, but it's still one of the greatest of all works and will be around as long as humanity is. What's it about? It's about people falling in love where they shouldn't, and where the person they're married to does not love them in the same way; it's not the subject matter that's problematic but the music, since it's so completely new in style that one has nothing against which to measure it. I think it's one of the most visceral, unbearably passionate operas I know.'

Keenlyside's future operatic plans include Siegmund and Posa, the former still just a possibility and the latter to be tried out in a concert performance in the U.S. What attracts him to these very different roles? 'I want to do Siegmund for the same reason that, say, a lyric tenor wants to do Lensky - because it's fantastic music, but I don't intend to make a habit of it, you know - it's just for fun! I find the top very easy, and I'll probably do it in concert first of all. Wagner is so spoilt by being sung only by huge voices; we know exactly what kind of sound he wanted, he built Bayreuth with the orchestra under the stage, so why can't we at least try to re -create the sound world of the one theatre that we know he approved of? As for Posa, he declares a love for what he calls 'just singing - old fashioned, bel canto, Italianate music, and things like 'Don Carlos' are full of such wonderful lyrical singing.'

I first encountered Keenlyside as a Lieder singer, his 'Jaegers Abendlied' (Schubert) on one of the Hyperion recordings making a strong impression on me with its warmth of tone, effortless production and air of tender intimacy, and he is as sought after on the recital platform as he is on the operatic stage. I have particularly admired the planning of his recitals, an area of special interest to me, but he was dismissive of any hint of a compliment ' No, they're not beautifully structured - I do it, but I don't structure them beautifully! How do you plan your life? It's chaos, isn't it?' I forbore to reply that no, it isn't, in fact my life is, has to be, anything but chaotic, but it's very clear that Keenlyside does not agonize over such things as recitals in the way that some singers do, nor does he especially concern himself with the reaction of the audience. One of his programmes begins with Schubert's'An die Leier,' in which the poet rejects songs of martial import in favour of 'Liebe im Erklingen,' but he says that this is not an observation about the music to come so much as something generally related to life.

He says that he 'adores' Hugo Wolf's songs, and those lucky enough to be attending this year's Schubertiade will be able to hear him in that composer's music along with songs by Schumann, Brahms and Schubert, in a recital with the mezzo-soprano Angelika Kirchschlager on August 31st; they will also open the Wigmore's 2002-3 season on September 6th. Visitors to Schwarzenberg will also have the opportunity to hear him in two Schubert recitals, songs by Goethe and Shakespeare on June 21st and 'Winterreise' on September 3rd. It is the latter song cycle which is foremost in his musical life at present, since he has been touring with it in Italy and elsewhere, and on March 25th he will present his interpretation of it at the Wigmore Hall for the first time. He says that he 'kept putting it off, mainly because there's so much more to do in the way of songs - every time I contemplated it I would start to think, I can't live without these ones! I also got fed up with people talking about singers who tackle it in their twenties in terms of 'Oh but wait until he's achieved maturity in his forties...' I don't know if I have achieved maturity or not, but one day I just thought, this is daft, I haven't done 'Winterreise' yet - so I'm going to.'

His collaboration with the choreographer Trisha Brown has led to his planned performances of 'Winterreise' in New York next December; these will incorporate two dancers who will serve as 'extensions of the voice' and what he describes as 'theme and variations.' He was highly amused to hear that I had received a publicity notice describing this as 'The premiere of Winterreise.' He agrees with Goerne that this great work is one which deserves special respect, although he says that he does not feel the weight of previous interpreters on his shoulders; he declares that he does not find the Wigmore Hall a nerve-wracking place to sing, and eschews the notion of having the music in front of him, since 'I need that newsreel in my head and I lose it if I see the lines in front of me.'

Keenlyside has come fairly late to what might be called English Song, since for him, there is 'too much other wonderful stuff - if it comes to a choice between the likes of Wolf and Britten, there's no choice at all, to me, except for the Blake poems which I do love! People ask me why I don't do much English song; they seem to think that I somehow have to because I am English, but I can't see it like that. I know there are singers who have an interest in it, but it's not something I see as a priority.'

He is not a much - recorded singer, but this does not worry him since he professes a distaste for the whole area of marketing and hype that accompanies the business; he says that if a recording comes along he's delighted and it's a privilege, otherwise, he'd rather make his own recordings which would serve as a 'diary of my life' even if they don't please him in musical terms. Nevertheless, he does confess to feeling 'quite proud' of his recording of Schumann on Hyperion, and so he should; he professes not to read any reviews, but the 'Gramophone' critic compared his 'Kerner Lieder' to the recording by Matthias Goerne, and it is certainly true that if one wanted a fine example of Keenlyside's art, one could hardly do better than the final song of that cycle, 'Alte Laute,' with its beautifully judged pianissimo; he says of this song that he had at first regarded it as bleak, with its final lines 'Auf dem traum, dem bangen / Weckt mich ein engel nur,' but later came to the conclusion that the angel could represent Love.

Apart from the 'Winterreise' and other forthcoming performances, his admirers can also look forward to a 'Barber of Seville' Figaro at the Met in April, when the combination of Keenlyside and Juan Diego Flores looks sure to produce some fireworks; he is also due to sing Count Almaviva in Vienna and Papageno in Salzburg, and London audiences will have the chance to hear him in that role at Covent Garden next January, when this sought - after baritone looks certain to delight London audiences once more with his beautiful singing and committed, highly charged stage presence.

Melanie Eskenazi

Photo by Catherine Ashmore, Simon Keenlyside as Don Giovanni at the Royal Opera.

Return to:

Return to: