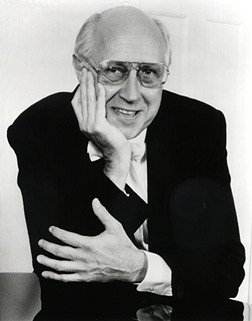

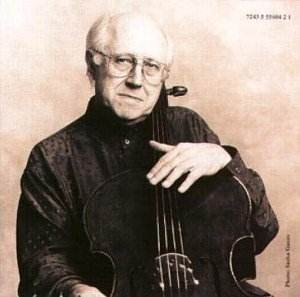

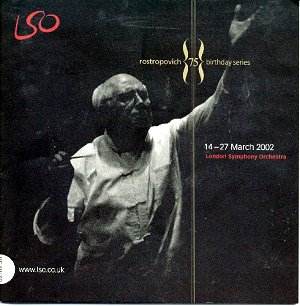

The great cellist-conductor Mstislav Rostropovich celebrated his 75th birthday on the 27th March 2002 and to celebrate this event Rostropovich has been performing with the London Symphony Orchestra in a series of concerts devoted to the three composers with whom Slava was most closely associated: Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Britten.

Anyone who attended just one of these concerts would have been aware of just how special these performances were (and for those who did not attend any there will, later this year, be an LSO recording of Shostakovich’s Eleventh Symphony, an extraordinary performance recapturing the essence of this great man). Our reviews below reflect a unanimity of opinion that these were indeed special events, often searing and often revelatory. The Gala Concert itself (with Slava as an onlooker) was a star-studded evening which it would be hard to recapture in words. Like the man whom we were celebrating it was for this critic a night off, a moment to just sit back and listen. True, we had bleeding chunks of works (concertos by Rachmaninov and Prokofiev, for example) but the level of inspiration was artistically the equal of everything which had preceded it. Rostropovich does not need to be on the podium as cellist or conductor for something special to happen; his very presence is often enough.

The reviews below are dedicated to one of the great humanitarians of our, or any generation. They are also a reflection of what great music making is all about.

Marc Bridle

Prokofiev, Romeo & Juliet (complete), London Symphony Orchestra & Lithuanian National Ballet, Mstislav Rostropovich, Barbican Hall, 14th March 2002 (MB)

This concert staging of Prokofiev’s ballet ranks as one of the greatest musical experiences in two decades of concert going; fully equal to hearing Karajan in Salzburg perform Mahler. Visually, it was often at odds with the level of inspiration being generated between conductor and orchestra and this makes it difficult to be objective about the evening as a whole.Problems of how the London Symphony Orchestra and the Lithuanian National Ballet were to be accommodated on the small Barbican stage were only partially resolved. The stage was lengthened at the front to cover the front stall’s seats, yet in reality this was only half a compromise. During the dance scenes even this extra space seemed inadequate with dancers appearing to be perilously close to the orchestral players. Neither did it always seem wise to have dancers rushing between two aisles which effectively divided the orchestra into three distinct sections. At the back was a raised dais which acted as a further setting for the dance element – and which provided the only sense of architecture to the design. This rather cramped setting meant much of the dancing was more tense than we might have expected– and with this there was an element of slipshoddiness to the steps, often unsynchronised and untidily projected. There was also slightly less drama about this performance than one might have wished for with lighting often glaringly bright or incomprehensibly dark making the balance between the story slightly skewed.

Having said that, the leads were generally fine. Egle Spokaite as Juliet was captivating, her Romeo Georgi Smilevski her equal in most respects. Their final scenes together did not quite match the intensity which Rostropovich generated from the podium, yet in part this was due to the conservative nature of Vladimir Vasiliev’s choreography which rather seemed to underplay the tragedy of the death scenes, and overplay so much else.

What really made this evening unforgettable was Rostropovich’s inspired conducting and the outstanding playing of the London Symphony Orchestra. Under certain conductors this orchestra has no peers and on this particular occasion was simply in a class of its own. Dressed casually in black the orchestra’s playing was anything but casual: it was fired by a stunning precision and a kaleidoscopic projection of colour that was simply breathtaking. Dynamics were often miraculous in their subtlety, but on this front Rostropovich has few rivals. The seating of the orchestra at first made me wonder how the sound would be projected (basses at the front, cellos and violins often with their backs to the audience, woodwind and brass placed at the back and sides); in reality, rather than hinder the sound it opened it up. Moments such as the Dance of the Knights had a thrilling immediacy, and the darker music of the Third Act often produced tone of overwhelming bleakness. Rostropovich often kept tempi fleet, although there were occasional moments of deliberate rubato (such as the Death of Tybalt), which although decimating in its delivery seemed rather less focused than it should be. The LSO followed him at every turn and one admired the concentration of their playing, particularly those musicians who were so close to the action on stage.

All in all, an evening which seduced the ear, but which one would rather have seen with one’s eyes firmly shut.

Marc Bridle

Shostakovich Denis Shapovalov (cello); London Symphony Orchestra, Mstislav Rostropovich. Barbican Hall, 19th March 2002 (CC)

It must have been daunting indeed for Denis Shapovalov (born 1974) to play Shostakovich’s great First Cello Concerto (why don’t we hear the Second more often?) under its dedicatee, Mstislav Rostropovich. The massive cheer for Slava can’t have helped. Hair-raising in its cellistic difficulties, Shapovalov had a mountain to climb.The opening Allegretto seemed faster than its indication (uncomfortably fast, in fact) and Shapovalov seemed to play on its surface. One marvelled at the superbly together string playing, not to mention the miraculous co-ordination between solo horn and cello, rather than the soloist’s closeness to the music. Later, Rostropovich brought a (batonless) sense of timelessness to the moderato. Shapovalov rose handsomely to the challenge of the Cadenza, however, and impressed most in the scampering finale.

The performance of the Eleventh Symphony that followed, however, must represent a highlight of the present concert season. If one had spent the first half of the concert wishing Rostropovich to be playing the cello, one spent the second wishing he had only ever been a conductor. This account was vastly superior to his recording with the National Symphony of Washington for Teldec (9031-76262-2) which does his interpretation little justice. The Eleventh Symphony was written in 1957 for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution and has always struck me as underrated (do the tiles for the four movements imply to audiences some sort of lack of profundity?).

Under Rostropovich the first movement (‘Palace Square’) was truly hypnotic, with perfectly delineated voice-leading adding to the still, tense atmosphere. The glacial opening and Rostropovich’s innate feeling for Shostakovich’s rate of harmonic change led to an Allegro (‘9 January’) in which meaning was injected into every note.

Rostropovich’s unapologetic way with both Shostakovich’s bolder statements and climaxes only emphasised the huge contrasts inherent in this piece. Special mention should go to the violas in the third movement (‘In memoriam’), who played with great emotional warmth.

The LSO seemed completely at one with Rostropovich’s ideas, and more than willing to put each and every one of them in to action. It was the inevitability and the sheer ‘rightness’ of the performance that left the audience both stunned and elevated.

This was inspired concert programming (the two works complementing each other beautifully), brought off with more than an element of greatness.

Colin Clarke

Britten: London Symphony Orchestra, Mstislav Rostropovich, Maxim Vengerov, John Mark Ainsley, Barbican Hall, 24th March 2002 (ME)

This celebratory concert was a real feast for Britten lovers, and found the LSO in magnificent form; indeed, it has been unusual, of late, to find them anything less thanthat. The ‘American Overture’ which began the concert was not one of the composer’s own favourites; indeed, he claimed to have forgotten having written it, and expressed the wish that it might be destroyed, but it is clearly a work which can bring out the best in a large orchestra under the direction of a confident maestro. The influence of Copland is fairly strong, and there are moments when you half expect it to slide into ‘Appalachian Spring,’ but the character of the music is stamped with Britten’s individual style.

The Violin Concerto followed, in a performance of dashing bravura from Maxim Vengerov. Britten wrote to the work’s first soloist, Antonio Brosa, that the work ‘will never be better played or more completely understood than it was by you…people realised what a task you had and how marvellously you overcame all the difficulties,’ and it is safe to assume that the composer would have been compelled to eat his words if he had heard this young violinist play his work. It would be natural for so youthful a soloist to focus especially on the more showy, bravura parts of the work, and indeed Vengerov gave them all he had, but it was in the lyrical first movement and the brilliantly shaped cadenza that he excelled; these were played with near-faultless intonation, exquisite clarity of technique and absolute commitment to the music’s shape. The orchestra gave him eloquent support, with some especially fine playing from the String sections; Vengerov and Rostropovich clearly have a special rapport, and it showed in every note.

Anyone who heard John Mark Ainsley’s recent Don Ottavio at Covent Garden on one of his less good nights and was concerned that his lovely voice might be feeling the strain, would have had any such worries assuaged by his performance of ‘Les Illuminations,’ since here he displayed all those qualities which make him a great singer; remarkable accuracy, with an unequalled sense of pitch; finely shaped phrasing; exquisitely eloquent delivery of the French words, with wonderfully secure and distinct articulation; seeming ease in management of the extremely difficult high- lying passages, and a sensuality that is deeply appropriate to both words and music.

Ainsley’s ‘et je danse’ from ‘Phrase’ demonstrated as clearly as any singing could, that here is a voice in its prime – he achieved that ecstatic slide up to the A with languidly sensual grace, and descended through the closing notes with eloquent poise. He did everything that Britten wanted; his singing of the ‘motto’ was exactly as the composer desired … ‘it must not lose its heraldic character’ and his evocation of the different atmospheres of the poems, encompassing eroticism and asceticism in almost equal measure, was masterly. There were a few moments when the orchestra threatened to swamp him, but it would be hard for any voice to rise above that huge mass of sound, egged on by Rostropovich, who seemed intent on whipping them along at a ferocious pace; obviously, a group such as the Nash Ensemble would be preferable accompaniment in this music. It would be difficult to imagine better Britten singing: what a wonderful Aschenbach he’ll make one day.

The concert ended with the Four Sea Interludes from ‘Peter Grimes,’ in a performance which fairly fizzed with excitement but perhaps missed some of the more elegiac qualities of this music. The first interlude, ‘Dawn,’ is supposed to evoke a ‘grey seascape,’ but I felt that the conductor was aiming more for an almost Mediterranean colour, particularly with the harp and clarinets, and indeed he was much more effective in ‘Sunday Morning’ with its highly expressive melodic shape. ‘Moonlight’ highlighted some superb playing although I did wish that Rostropovich would not keep his head so deeply buried in the score during such passages, and the final ‘Storm’ was as sublime (in the 18th century sense) as I have ever heard it, with the brass and woodwind sections in particular evoking the tumult not only of the storm at sea but also of the tempest that overwhelms the opera’s protagonist.

A fitting tribute to one of today’s greatest musical figures.

Melanie Eskenazi

Return to:

Return to: