During the fortnight of Strasbourg's International Festival of New Music

Musica, four operas were given in the city that deserve attention,

as does a presentation of Bach's B minor Mass on the heels of the recent

dramatisation of his St John Passion by ENO in London. Karol Szymanowski's

Le Roi Roger is rarely staged because of its extravagant

and costly scenic demands despite having limited dramatic action, its

ritualistic features related to oratorio and to medieval mystery plays.

It was introduced in a lecture by the composer's devoted champion, Harry

Halbreich, who places the composer's importance (and especially this

opera) as equal to that of Bartok, whose Bluebeard's Castle was

given by the BBC in this year's opening Musica concert.

Both Halbreich and Jan Latham-Koenig, director of the Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra and of this production, and another dedicated Szymanowski devotee, believe that Le Roi Roger is unsuitable for 'modernisation'. King Roger II and his Queen Roxane are captivated by a strange shepherd, who is turning heads of the populace, and the opera deals allusively with homosexual and Dionysian seduction. The overheated score builds to sumptuous, overwhelming climaxes, not to everyone's taste, but well conveyed by the Strasbourg orchestra and soloists from Poland, with the Varsovie opera choir and a well trained girls choir, Alla Polacca.

Unfortunately, Szymanowski's dense orchestral textures presented insuperable balance problems at the first of the two performances, frequently covering the soloists, and making it very necessary to help the ears by reference to the complete libretto (in four languages) thoughtfully provided free of charge to everyone at the Palais de la Musique. Radoslaw Zukowski, bass (the Archbishop) and Adam Zdunikowski, tenor (the mysterious Shepherd) coped particularly well in the circumstances, but really an opera pit is essential. Halbreich believes that the best solution would be to make a video/DVD in the Sicilian locations at Palermo, Monreale and Syracuse specified meticulously by the composer.

Giorgio Battistelli (b1953) is something of a maverick. He has several

operas to his name - the two played this year in Strasbourg far from ordinary.

Impressions d'Afrique (2000) treats a bizarre text

by Raymond Roussel (1877-1933); an unsuccessful writer who never visited

Africa, so his impressions are far from authentic, indeed are totally

incomprehensible and defy logical interpretation or easy description.

But the stage pictures and costuming by a team headed by Georges Lavaudant

and Jean-Pierre Vergier are highly seductive, with a strong cast of actors

and singers and dancers and powerful singing and orchestral playing by

the Choeurs de l' Opéra National du Rhin, Strasbourg and the Orchestre

Symphonique de Mulhouse, under the direction of Luca Pfaff, whose way

with difficult contemporary music had recently been admired in Lisbon.

The production went on to Colmar and Mulhouse, and gave great pleasure

to audiences that emerged perplexed by its irrationality.

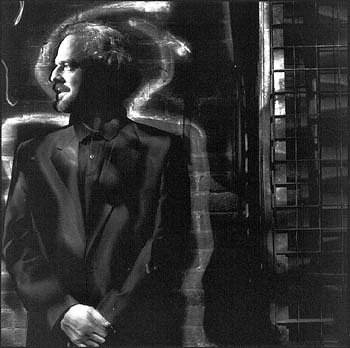

Experimentum mundi - opera di musica immaginistica

(1980) is a unique theatrical conception that has been successfully toured

during the '80s and has been seen at the Huddersfield Festival. Opus/opera

mean work/works, and Battistelli seized upon this with meaning a vengeance.

The main musical material is built from repetitive occupational sounds

produced by a group of artisans and their women plucked out of Albano

Laziale, the composer's own native village near Rome, and put onto the

world's stages. They paved, built a brick wall, hammered metal, wood,

stone & leather, planed wood, cracked eggs etc, 'choreographed' precisely

- some of the craftsmen following scores - all rigorously controlled by

Battistelli. Expressionless, immobile between their bursts of activity,

the tempo was sometimes steady, at others whipped accelerando to

a frenetic presto by the director/controller, Battistelli himself,

whose extravagant gesturing and jumping caricatured the excesses of self

regarding conductors who conduct the audience, not the orchestra.

Battistelli - (photo Marthe Lemelle)

The minimal music created by the villagers was augmented by a professional

percussionist (Nicola Raffone) and 18 C. encyclopaedia texts about the

various crafts were declaimed rhythmically by Bernard Freyd. The show

was superficially very entertaining (at least for its first half hour,

which exhausted the repertoire of gestures) and tapped into everyone's

interest in watching work (viewing platforms in building sites, Verdian

and Wagnerian metal work and cobbling!). It was warmly received as such,

but worked on many levels, notably as a metaphor for the tedium of repetitive

work in general, and perhaps that of regimented orchestral players in

particular, and left one - deliberately I hope - uneasy about the audience's

collusive voyeurism? The expatriate Albano Lazialians evinced no pleasure

in their participation in this show; I do hope they were well remunerated!

Salvatore Sciarrino (b.1947) is a prolific, important Italian composer known in the UK through occasional airings of music which often tends to the lower limits of audibility, and concentrates on the expressive possibilities of sounds made by instruments which the players usually seek to eliminate or minimise, an area explored also by Helmut Lachenmann to very different effect. Lohengrin - 'opéra en un acte de Salvatore Sciarrino' was conceived by its composer as an opera with action invisible, for one singer/actress who assumes all the characters. A major concert work of 1982/84, it has been revived brilliantly as a staged opera in an imaginative realisation by Ingrid von Wantoch Rekowski, which should give it a new lease of life.

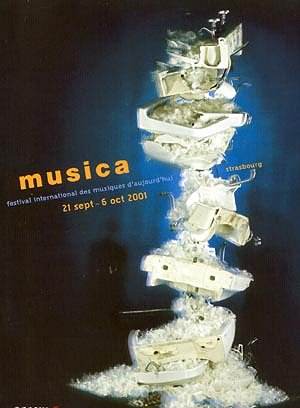

Viviane de Muynck is supported by the New Music Chamber Ensemble of Berlin under the direction of composer/conductor Beat Furrer. This realisation begins with Viviane de Muynck alone on the stage, a feather between her lips, a clue that Wagner's Swan was to assume enhanced importance in this version. That aspect of Sciarrino's conception is taken up in a sculptural installation, by Fred Pommerehn and Rekowski herself, which was distributed around the theatre foyers and chosen as the image for the Strasbourg Musica festival publicity, in flags and posters all around town, and for the cover illustration of the programme book.

For

most of the thousands who will have seen it, the image will remain as

obscure and impossible to decipher as was the significance of a burning

shed gracing the cover of the Huddersfield 2000 programme book when Richard

Steinitz was retiring. For the record, the Rekowski/Pommerehn installation,

which I by no means seek to disparage, was created from sanitary ceramic

bric-a-brac, and the chosen sculpture, illustrated in the photo on view

everywhere (deliberately blurred - I am assured - with a secondary 'ghost'

image like those some of us suffer on TV), consists of a pile of broken

wash basins filled to overflowing with swan feathers! No one I quizzed

had the faintest idea what it was; one critic who had reviewed the show

assumed it was a map of Great Britain, but could not think why! Someone

should warn producers of these important publications not to be too clever

with insider references, comprehensible only to those in the know.

For

most of the thousands who will have seen it, the image will remain as

obscure and impossible to decipher as was the significance of a burning

shed gracing the cover of the Huddersfield 2000 programme book when Richard

Steinitz was retiring. For the record, the Rekowski/Pommerehn installation,

which I by no means seek to disparage, was created from sanitary ceramic

bric-a-brac, and the chosen sculpture, illustrated in the photo on view

everywhere (deliberately blurred - I am assured - with a secondary 'ghost'

image like those some of us suffer on TV), consists of a pile of broken

wash basins filled to overflowing with swan feathers! No one I quizzed

had the faintest idea what it was; one critic who had reviewed the show

assumed it was a map of Great Britain, but could not think why! Someone

should warn producers of these important publications not to be too clever

with insider references, comprehensible only to those in the know.

The instrumentalists entered to perform Lohengrin one by one, clambering in slow-motion over the enormous curving bench on which Viviane de Muynck sits (the only prop) - uncannily, this was anticipated for us by a delightful trio of two mime/dancers with an accompanying musician, who climbed balletically around the seats of our carriage en route by train to Strasbourg, not even soliciting payment for a unique onboard entertainment. Both conceptions clearly shared a current artistic vogue!

This slow, silent prologue established a level of anticipation and listening intensity which was sustained through the hour of this opera's traffic upon the stage, a prologue, four scenes and epilogue, given without a break; not all reactions afterwards were as enthusiastically positive as ours. Before voicing the feelings of Elsa herself at her nuptials, Viviane de Muynck uttered tongue clickings and throat sounds to represent the voice of the symbolic mute bird at the centre of the internal drama played out by Sciarrino, who also wrote the libretto. A 'choir' of three male singers punctuate the action occasionally and mime emotions, such as Lohengrin's boredom with a betrothed who had the wrong sort of hips for his liking (they're too small)! Viviane de Muynck was astonishingly resourceful, presenting, mainly from the perspective of Elsa, the mismatch with a crassly insensitive, unfeeling Lohengrin, but also assuming the latter's own disparaging and dismissive voice, and even becoming Lohengrin's Swan (renowned in operatic history anecdote), images of which increasingly dominate Elsa's idealised fantasies of the loving man she had hoped for as she succumbs to despair and madness.

All this is reflected in the most compelling and impressive of Sciarrino's scores which I have met with. It moves in broad spans, supporting and punctuating the internal drama, with a dynamic range between nearly inaudible, yet engrossing, tappings and scrapings, to scary outbursts from the full ensemble, reflecting the (internal) action, the instrumentalists dressed in high winged collars to pick up the prevailing swan imagery. Viviane de Muynck wears a microphone which picks up and amplifies the smallest of her vocal sounds, which are familiar but, as with those produced usually involuntarily by instrumentalists, are generally suppressed or ignored. The music is at once recondite and readily accessible, provided pre-conceptions are put aside. Sciarrino takes the innovations of Berio in his Sequenza for Cathy Berberian to a new dimension, and our contemporary music singers should be competing with opportunities to present it, whether staged or in concert performance.

This haunting production, one of the most convincing pieces of modern music-theatre I know, will be seen on December 2 at Huddersfield, preceded in the morning by a Portrait of Sciarrino. Meanwhile, there is a CD to seek out, directed by the composer with Daisy Lumini & Gruppo Strumentale Musica d'Oggi, on the Agora/Ricordi label.

Ingrid von Wantoch Rekowski

- (photo Marthe Lemelle)

In

H moll , premiered in Musica on 4 October, was provisionally entitled

Corportentum and is even more radical than Ingrid von Wantoch

Rekowski's Lohengrin, and its many-layered glosses upon

that sacrosanct pillar of Christian sacred music, J S Bach's Mass in B

minor, are virtually impossible to convey in words. The music itself is

treated with affection and sincere appreciation, though, paradoxically,

not without humour - indeed paradox is the essence of this presentation.

The score is stripped down to one hour, and is sung without any instrumental

accompaniment by 10 actors, none of whom are trained singers. There are

unaccompanied solos, often given mezza voce and without vibrato

and with reversals of expectation; the Et ressurexit is sung pianissimo,

and after the crucifixion there is a 'wake' with drinking and ribald humour.

The only musical instruments are little hand-bells worn by each of the

singing actors and used, as in church, to focus attention but not excluding

irreverent by-play with the bells. They also served to establish pitch

for the choral singing; intonation was notably excellent however controversial

the singing style.

In

H moll , premiered in Musica on 4 October, was provisionally entitled

Corportentum and is even more radical than Ingrid von Wantoch

Rekowski's Lohengrin, and its many-layered glosses upon

that sacrosanct pillar of Christian sacred music, J S Bach's Mass in B

minor, are virtually impossible to convey in words. The music itself is

treated with affection and sincere appreciation, though, paradoxically,

not without humour - indeed paradox is the essence of this presentation.

The score is stripped down to one hour, and is sung without any instrumental

accompaniment by 10 actors, none of whom are trained singers. There are

unaccompanied solos, often given mezza voce and without vibrato

and with reversals of expectation; the Et ressurexit is sung pianissimo,

and after the crucifixion there is a 'wake' with drinking and ribald humour.

The only musical instruments are little hand-bells worn by each of the

singing actors and used, as in church, to focus attention but not excluding

irreverent by-play with the bells. They also served to establish pitch

for the choral singing; intonation was notably excellent however controversial

the singing style.

Upon a bare stage at Strasbourg's Palais du Rhin, backed by

Corinthian columns, the performers take the groupings, contorted postures

and facial expressions of their miming from the iconography of early paintings,

and especially the caricatured representations of Hieronimous Bosch, with

their pertinent depictions of human imperfection and carnality, and of

hypocrisy. The women are attired by Christophe Pidré in provocative

corsetry and the men have fur trimmings, both with erotic connotations.

It is physical theatre choreographed by Rekowski, with each actor strongly

individuated, and combining in set-piece tableaux which are hilarious

to watch. Many of the poses and gestures are taken from those familiar

in sacred art and in the never-changing church ritual. Overt mockery of

the ritual repetition of the core text of the Mass every week in church

and cathedral is central to Rekowski's questioning of heavily defended

beliefs and practices that are supposedly a key basis of 'civilised' life

and its social and personal interactions, a stance which been thrown into

high relief by the recent international catastrophe and the polarisation

of religions and of secular non-religious beliefs. The provocative presentation

of the Christian Mass in such a manner will surely cause some offence,

but In H moll was rapturously received by the Strasbourg

audience, and for us will remain one of the most enduring memories of

Musica 2001.

Peter Grahame Woolf

In H moll is touring to Brussels (9-20 October), Ghent (23/24

October) and Anvers (26/27 October) and the Sciarrino/Rekowski

Lohengrin can also be Heard & Seen at

Nanterre, 12-15 December (www.tem-nanterre.com)

after its staging at the Huddersfield Festival on 2 December.

Return to:

Return to: