By a happy mischance for the 10 October Covent Garden audience, the veteran Anja Silja had returned to the Royal Opera House for Jenufa, in the role for which she is famous. Deborah Polaski had withdrawn for medical reasons, and the house managed

to persuade her to step in to sing the Kostelnicka once again.

Eva Randova, a former Kostelnicka, gave a reticent presentation of Grandmother Burya in a smaller singing part, emphasising frailty and poor eyesight by tapping around the peculiar set with a stick, this limiting her important presence. Karita Mattila sang beautifully as Jenufa, her vocal production easy through all registers, but I found her more conventional and less touching than Roberta Alexander on the Glyndebourne DVD. Jorma Silvasti sang strongly and convincingly portrayed the conflicting emotions which tore Laca apart, his violent disfigurement of Jenufa's beauty the catalyst for the tragedy that followed. The other parts were mainly well taken. The final reconciliation, expressing hope for possible future healing and happiness, was made credible by the warmth of Janacek's music.In Olivier Tambosi's production, which originated at the Hamburg State Opera House, the triangular relationships were simplistically represented by a triangular stage. There was no credible sense of space, whether outdoors, or in what should be the claustrophobic interior of the shuttered house in which Jenufa was hidden away with her shame. Polystyrene rocks of various dimensions dominated the Schossmann designs, serving to show the weight of troubles besetting the family, and providing the only furniture for the disrupted wedding gathering, with little stones conveniently placed for the villagers to pick up, in order to threaten to stone Jenufa to death, when the dead baby has been found.

The particular strength of this musically powerful revival of Janacek's early masterpiece lay in the use of the Mackerras/Tyrell 1996 reconstruction of the 'Brno 1908' version of the score.

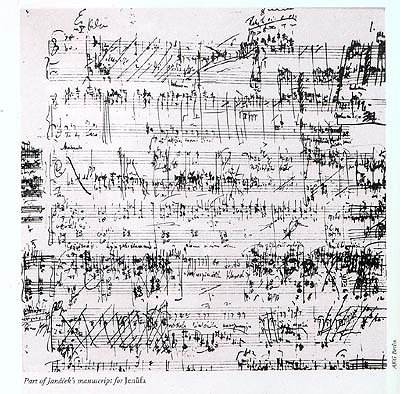

[ Part of Janacek's manuscript for Jenufa]

Amongst the comprehensive collection of essays in the collectable programme book, John Tyrrell discusses Jenufa's vicissitudes in full detail. My illustration (illegible to ordinary mortals even as seen in larger scale there) indicates their mammoth task in restoring Janacek's original intentions. Janacek had only managed to get Jenufa mounted in Prague, following a 12-year refusal, by accepting conditions imposed by Karel Kovarovic that he, Kovarovic, should cut and re-orchestrate the work! Unfortunately, even the published version of 1969 by Universal gave 'no hint that Janacek's own voice had been muzzled'.

Under Bernard Haitink, during his last season as Musical Director, the orchestra sounded magnificent in the 'Brno 1908' score, which must now become standard. They conveyed brooding menace and foreboding of certain disaster, and glowed unforgettably to counterpoint the themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Haitink and his players received the loudest and most prolonged of the many ovations.

Despite that unquestioned advantage, this revival could not hold a candle to Lenhoff's historic production of Jenufa. Two reviews of its recent revival at Glyndebourne http://musicweb-international.com/SandH/2000/june00/glynebourne.htm will have left Seen&Heard's readers in little doubt about its surpassing excellence and long-term viability. It is a great satisfaction to have been able to revisit the original production in the newly released DVD Arthaus 100 208, conducted by Andrew Davis and well remembered from its showing on TV (1989), with Roberta Alexander (three of her Etcetera song recitals are favourites in my collection, especially Copland on KTC 1100) totally consumed by the plight of Jenufa herself, with a face which reflects every mood from cowed despair to unbelieving hope at the end. Anja Silja is implacable as the Kostelnicka, but wins your empathy by the end. Philip Langridge is explosive as Laca (nowadays he would qualify for the attentions of the social workers and their risk registers) and tender in the transformation, which works its way through his character and in the relationships of this vulnerable, dysfunctional extended family group.

I found the sub-titles here a great boon, and am somewhat in disagreement about sur-titles in the opera house with Hans-Theodor Wohlfahrt, who celebrated especially Anja Silja, still in 2000 dominant in the same role. Of course, on the screen you do not have to look in different directions as in the opera house, and can take them in almost subliminally (or switch them off!). They clarify the motivations in detail, and there is scarcely a phrase in the compact libretto that is not significant in driving the action.

The first act takes place in a naturalistic setting outside the mill, and then gradually you are taken into the rooms, which become oppressive and claustrophobic. The wedding scene is fraught with tension, relieved by a few moments of mayhem introduced by Lenhoff, which really shock. Sometimes you feel uncomfortably close to the actor-singers, who are of course projecting their emotions into a fairly large opera house, but the camera decisions are on the whole sensible in focusing in and then drawing back.

The little rococo theatre in Schwetzingen Palace was the ideal venue for Monteverdi's Poppea from the 1993 Schwetzinger Festival http://musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Apr01/DVDMonteverdi.htm, and for Salieri's Falstaff, and its small scale helps to make the best possible case also for Rossini's opera seria Tancredi. Taken from the 1992 Schwetzinger Festival, the music in this performance, filmed live, is entrusted to the experienced Rossini specialist, Gianluigi Gelmetti, who gets exactly the right style from the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, which we have enjoyed in several Stuttgart Eclat festivals http://musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Feb01/stuttgart-2-01.htm and very recently at the Musica 2001 festival in Strasbourg.

Design settings, and Sicilian baroque costumes, are unified by the director per Luigi Pizzi, and the stylised movements are exactly right for the formality of the genre. Originally given in lavish productions, no doubt, this small scale version on Arthaus 100 206 works well for the small screen. Gradually you are swept into the mood of the dramatic, if predictable, plot and the predicaments of Bernadette Manca di Nissa, the mezzo hero in the travesty role of the eponymous hero, and Maria Bayo, an affecting and vocally accomplished soprano victim of state circumstances and of the implacable unyielding autocracy of a heavy-handed King and father, Raul Ginenez. The aggrieved rejected suitor, Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, makes an escape from death possible after all, and the audience enjoys the reprieve of Rossini's alternative 'happy ending' which brings back to full vigour the dying Tancredi and ends the show on a high note. You start by mocking a little and wishing it was one of the comedies; gradually the inventiveness and power of the music takes over and you realise, perhaps in Amenaide's moving dungeon scene, that you may have got Rossini wrong - the annual Pesaro Rossini Festival has forced a radical revaluation, and the Rossini renaissance is in full swing.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Excerpt from the Sunday Times review of the R. O. H. Jenufa, by Hugh Canning:

- - At the horrifying climax of Act II of Janacek's Jenufa, Kostelnicka Buryjovka abducts her stepdaughter's sleeping baby from its cot and takes it out into a snowstorm to drown it under the winter's ice. No sooner is she out of the door than Jenufa, dreaming in a drugged slumber, cries out that a rock is falling on her. This symbolic rock is the idée fixe of Frank Philipp Schlössmann's set design for Olivier Tambosi's staging, first seen at the Hamburg State Opera three years ago, and now "re-worked" as a "new" production for the Royal Opera.

In Act I - usually set in the environs of the Buryja mill, whose turning wheel Janacek graphically depicts in his orchestral prelude - Schlössmann's rock is bursting up through the floorboards of a vast barn; in Act II, it is the only feature of the Kostelnicka's otherwise unfurnished home; and for the Act III wedding party, it has become symbolically fragmented. Conveniently, too, for the Kostelnicka now has lots of little rocks for her guests to sit on, and the very small ones come in handy when the populace threatens to stone the apparent infanticide after the tiny body is discovered under the melting ice.

This is Britain's first designer-chic Jenufa, and, on its own terms, it looks, well, terrifically chic. But in the missing-the-point annals of opera - admittedly a jam-packed catalogue - Tambosi's staging surely ranks among the most fatuous. It should come as no surprise that this production was deemed a "sensation" by the public and critics alike in Germany, presumably because of its sensational lack of interest in the oppressive social milieu and claustrophobic atmosphere of Janacek's shattering domestic tragedy, and its sensational fascination with the symbolism of rocks. - -

Return to:

Return to: