Triangel Ensemble Intercontemporain/ Jonathan Nott with

Michel Cerutti (percussion) 22 September 2001 Palais de Fêtes

Windsequenzen Accroche Note and musikFabrik/Philippe

Nahon 3 October, ZKM Karlsruhe, Germany.

Brass: The Metal Space Ensemble Brass in the Five, 6

October, Museum of Contemporary Art

Septieme Porte (film portrait of Peter Eötvös

by Judit Kele, 6 October, Museum of Contemporary Art

Atlantis SWR Radio-Sinfonieorchester/Peter Eötvös

6 October, Palais de Musique et des Congres (PGW)

[PICT Peter Eötvös

(photo Marthe Lemelle)]

Peter Eötvös (b.1944) grows in stature with exposure in

depth to his richly varied oeuvre, and Musica has done

well to feature him handsomely in a generous retrospective at Strasbourg.

In the very desirable programme book there is a five-page article about

Eötvös which, in discussing his Triangel, notes how

its air of 'anti-authoritarian autonomy' reflects the spirit of the

'60s. He continues to explore relationships of sound and structure,

and those between performers and audience, and each of the pieces we

heard had a spirit of adventure.

Triangel (1993) was the first of six

works (plus a film) which were given in separate events throughout the

festival. Triangel has been recommended to previously MusicWeb

readers on CD (BIS

948), but was infinitely more exciting experienced live. It is a

major work for a large ensemble of 27 instruments, lasting over 40 mins,

with a dominant 'creative' percussionist, Michel Cerutti, who acted

as a master of ceremonies, as in African drumming, moving around the

stage and freed by the composer to take musical decisions during the

performance and determining 'tasks' for each group in turn.

Triangel begins with an offstage tinkling and

a sole player entering, making apparently desultory sounds on the triangle

he carries. Other instrumentalists enter from time to time and regroup

to play successive sections from different parts of the platform. In

one section Cerutti brings in eight wind soloists, each appearing to

improvise individually in turn and continuing to do so collectively,

the process initiated upon Cerutti's signals on metal plates ranged

between them. In another section strings, in groups of three from high

to low, were energised by Cerutti successively on three steel drums,

making a piquant contrast of timbre, building up to a powerful climax

involving the whole ensemble. Later Cerutti had a tremendous tympani

solo and towards the end of the work a passage that concentrates upon

dazzling resonances from three amplified triangles. A great concert

work, and one which would be ideal for video or DVD.

Eötvös's Windsequenzen (1975-1987),

given by the combined ensembles of Accroche Note (Strasbourg)

and musikFabrik (Dusseldorf), made for a satisfying culmination

of a cultural exchange evening of variable quality, across the border

in Germany.

The entire Strasbourg-based audience was transported

free of charge in four coaches, and supplied with food boxes on every

seat, to the Centre for Arts and Media Technology (ZKM) in Karlsruhe.

This was a former converted munitions factory, which had survived heavy

bombing of the city, and has been converted into a multi-purpose arts

centre with three serviceable auditoria, in two of which the groups

had each given short concerts earlier.

FromAccroche Note, the young Polish composer Marzena Komsta's

Journal en rafales (papers flying into the air in whirlwinds)

showed an individual quality to make her name one to look out for. A

video/electronic creation by the Portuguese Paolo Ferreira-Lopes held

attention with its audio-visual competence, and as a good vehicle to

admire Françoise Kubler's voice and magnetism, her image discernible

from behind the screen; however, it has to be said again that some of

the abstract images, sweeping repetitively up and across the large screen,

showed little advance upon familiar computer screen-saver patterns,

as had been the case with earlier video presentations during the festival.

Windsequenzen comprised a series of sections,

framed by Calme I and Calme II, twenty minutes later.

The intervening music was given poetic titles by Eötvös, added

after its completion, with sequences of morning wind, mountain wind,

whirlwind and sea winds from different points of the compass. The spirit

of the work is one of serenity expressed in harmonic movement, its essence

'impregnated with the paradoxes of Zen Buddhism; serenity within movement

& movement within serenity - immobility which contains within itself

the possibility of movement, a readiness for something to happen'. The

instrumentation is unique, with flute, oboe/cor anglais, 2 clarinets

+ bass clarinet, double bass, tuba, percussion and harmonium. There

is a long flute solo - the wind instrument closest to the natural sounds

of wind itself - and later a trio passage for flute, tuba and harmonium!

The oboist has an additional role as vocalist, evoking the wind itself

by blowing gently through his lips into a microphone, producing sibilant

sounds which were neither singing nor whistling; far more convincing

in a musical context than the usual orchestral wind-machine. A truly

unique 'one-off', unlike any other music, and just the sort of thing

one looks for in a festival.

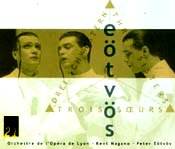

Peter Eötvös dominated the last day

of Musica 2001. In the afternoon, at the Museum of Contemporary Art,

the film portrait Septieme Porte by Judit Kele (1998) was shown

in the composer's presence. The title's allusion is to the secrets of

Bluebeard (we see him  conducting

the Bartok opera) and to 'un artist aussi secret', to whose very private

composing room we were taken, where in isolation he creates his music

with just a small piano for company. There are shots of Eötvös

working with Stockhausen, and rehearsal extracts from his important

opera The Three Sisters, those roles taken by three counter-tenors.

Its world premiere in 1998 is available on a lavishly produced and highly

recommendable live recording [DG

459 694-2].

conducting

the Bartok opera) and to 'un artist aussi secret', to whose very private

composing room we were taken, where in isolation he creates his music

with just a small piano for company. There are shots of Eötvös

working with Stockhausen, and rehearsal extracts from his important

opera The Three Sisters, those roles taken by three counter-tenors.

Its world premiere in 1998 is available on a lavishly produced and highly

recommendable live recording [DG

459 694-2].

In the gallery's main central space the Budapest Ensemble

Brass in the Five gave two performances of Eötvös's "jeu

acoustique" Brass: The Metal Space. This event was close to my

heart and to a long-standing preoccupation of Seen&Heard. 'Sound

that you hear is the sum of the sound of the instrument and of the space

in which it is heard', writes Eötvös and this composition

explores in a multiplicity of demonstrations how sound is changed by

moving the sound source around. Between the two performances there was

a lecture-demonstration by Janos Pap, Professor of Acoustics in Budapest,

which underlined my interest in the importance of concert hall acoustics

(see Sound

in Silence, Lucerne) and my contention that reviews which

aim to assess performances with some objectivity in certain halls may

need to specify where the critic was sitting, which can make a huge

difference to the overall effect of a concert performance.

Sitting close to the players for the first rendering

of Brass: The Metal Space some of the intended differences were

minimised, because most of the sound was received from the instruments

direct; high up under the roof for the repeat performance, all the intended

effects came vividly to life. This entertaining composition has a real

value in encouraging concert goers to 'ouvrez bien vos deux oreilles',

as Eötvös writes, and would be a huge success if introduced

in concerts for young people.

To conclude the whole festival, Peter Eötvös

conducted the Stuttgart based SWR Radio-Sinfonieorchester in a revival

of his Atlantis (1995) at the huge concert hall of the

Palais de Musique et des Congres. For Eötvös, Atlantis

symbolises terrifying natural catastrophe and also signifies social

and ethical conflicts which manifest themselves; like Atlantis, he places

the audience 'under the sea' as the work commences, surrounded by his

'fantastic sonic universe'. The eight percussionists are placed around

the stage and three distributed around the back of the auditorium. There

are five electronic keyboard instruments and live electronics spread

the sound around us impressively. A moderate sized orchestra is called

for otherwise, with only ten strings but some unusual wind instruments,

including double-bass tuba, and an important part for cimbalom (Marta

Fabian).

The text by Sandor Weöres was not supplied in

any language (a similar lack was even more crippling for Luca Francesconi's

new work in the first half, a massive and relentlessly loud modernist

score with declamation of text by a reciter almost throughout, mainly

in Italian). Two remarkable singers took part in Atlantis and

one could enjoy them without knowing what they were on about - Gregor

Dalal, baritone - but he sang also falsetto in the counter tenor range

- and a confident unnamed boy who offered splendidly controlled tone

and long, smooth glissandi with impressive aplomb. I had not come across

this work, which is said to be available on CD (?), but that could not

be any substitute for experiencing it in a suitable space; Atlantis

would be well received at one of the Barbican's contemporary music

showcases, and would sound magnificent at the Royal Albert Hall. But

this must be a costly score to mount and Musica must be congratulated

in organising so spectacular a finale for the festival - and inviting

the whole audience afterwards to an open buffet with wine for us to

take our farewells.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Return to:

Music on the Web

Return to:

Music on the Web