Haydn The Seasons Orkest van de

Achttiende Eeuw/Rattle, Nederlands Kamerkoor & soloists Oelze, Ainsley

& Wilson Johnson, 27 February

Bartok, Janacek & Shostakovich Radio

Philharmonic Orchestra/ Flor with Peter Donohoe (piano) De Doelen, Rotterdam

3 March

The Gaudeamus Interpreters Competition must be one of the most prestigious and best organised of international contemporary music competitions. It is genuinely international, attracting musicians to the Nederlands from all corners of the globe, this year's semi-finalists originating from Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Finland, France, Holland, Poland, UK & USA, Venezuela & Yugoslavia. The competition was part of the Rotterdam Music Biennial, and included, alongside adjudicated test sessions, daily concerts and master classes, which were held in the Muziekzaal, Theaterzaal and teaching rooms of a splendid new building, recently completed, which houses the city's Conservatory of Music and Academy of Dance. The final session was recorded for the Dutch Radio 4 station from the immediately adjacent Juriaanse Zaal of De Doelen, the whole huge complex for the arts situated right at the hub of Rotterdam, close to its Central Station, and an architectural delight.

|

|

For visiting listeners hors de concours it was a wonderful week of

music making by numerous gifted younger musicians, all of whom demonstrated

that they have a great deal to offer the wide and various musical world.

The overall winner was Tony Arnold,

[left] an American

singer who presented a theatrical programme of Aphergis Recitations

and Ades' song about swapping Life Stories, with its nasty sting in

the tail, and was awarded the first prize of NLG 10,000. The recorder player

Jorge Isaac swept up the 2nd prize of NLG 5,000

and a similar sum for the best use of electronics. The third prize of NLG

2,500 went to pianist Sarah Bob from USA, and the other finalists

were flautist Karin De Fleyt & accordionist Veli Kujala

who are mentioned below. It is good to know that, in addition to the money

prizes awarded to three of the finalists, Gaudeamus will offer to all the

finalists concert engagements and workshop possibilities, in their own festivals

to come and also at Dutch conservatories and concert venues.

Entry fees for the Interpreters Competition are modest, but competitors are responsible for their own travel and accommodation. There were more than 70 contenders for the all too few Gaudeamus prizes, accepted for registration unheard on the basis of their experience and repertoire offered. Soloists had to be not over 35 at the end of the competition week, ensembles of average age not over 35 and singers were admitted up to 40.

The jury members were noted instrumentalists, and themselves chose most of the programmes from lists submitted by participants. The rules required compositions from after 1940, to include three written since 1985, two works by Dutch composers or residents, and (optionally) one extra item from the early decades of the 20.C. The special theme for this year, in which Rotterdam is the Cultural Capital of Europe 2001, was electro-acoustic and live electronics music, with a special prize for the best use of electronics by a participant.

Ton Hartsuiker, pianist-jurer and former director of the Amsterdam Conservatory, told me how the format had developed since its inauguration in1963, when he won second prize. It had produced for us listeners a superb, balanced repertoire from which were constructed programmes of enormous variety and unfailing interest, and which were unlikely to tire listeners or jurors through what might otherwise have become a gruelling endurance test for all who stood the course. We were able to hear all the semi-finalists and attended a sufficiently substantial sample of first round recitals to form a positive view of the high prevailing standard. Their selections of scores offered are appended to this report and could function as a valuable source-list for younger artists seeking to extend their repertoires of unfamiliar music which 'works well' in performance

The adjudication between soloists and ensembles, singers and players of all orchestral instruments from recorder to saxophone, violin to double bass, piano to harpsichord, cimbalom and even toy piano, made for the jury of five instrumentalists a daunting and virtually impossible comparative task to resolve in their discussions. As veteran music lovers and critics our choice of finalists would have been different, but we say so with due humility, not having had access to the scores, nor did we hear every session, and, importantly, we held no practical responsibility for the effects of our opinions. Our comments are intended to be helpful and must be taken as personal and necessarily tentative.

Memorable performances

Most of the string players were eliminated early, but a very long-lasting memory will be an over-the-top presentation by Polish double-bassist Aleksander Gabrys of his father Ryszard Gabrys' ironical take on An die Freude from Beethoven's 9th, accompanying himself whilst vocalising dramatically from high falsetto to deep bass. Finnish piano-accordionist Veli Kujala who reached the finals, brought a smile to the jury's faces with his rendering on the bayan (button-accordion) of Ligeti's Hungarian Rock for harpsichord, but we admired more the consummate musicianship and virtuosity of his Yugoslavian rival Snezana Nesic, who played all her programmes by memory and conveyed complete identification with the different styles and emotional worlds of each composer. Amongst several pianists, we would certainly have awarded the palm to Heather O'Donnell, who gave the best performance we heard of Jonathan Harvey's popular Tombeau for Messiaen for piano with tape, despite the constant balance control by the operator, upon which it depends for its full realisation, not having been forthcoming. She played with easy mastery and very evident enjoyment a good range of music from Ulrich Leyendecker's tiny, scintillating Chopinesque Bagatelles to Automne a Varsovie, the most evocative of Ligeti's brain and finger-twisting studies. Her two semi-final recitals concluded with as fine an account of one of the most modern of 20th C. piano works (Ives' Hawthorne of 1912!) as you are likely to be lucky enough to encounter. Amongst woodwind players, I enjoyed the charm of flautist Karin de Fleyt running in and out, a pied-piper in Stockhausen's Flote aus Orchester-Finalisten, surrounded by the taped sounds of children in a playground, but will remember longer (and hope to hear soon again) Monika Mattiesen, an immaculate and expressive Estonian flautist who gave a perfect Berio Sequenza and Saariaho's Noa Noa, an evocative composition with live electronics, which unfortunately failed to work properly in the last page.

The special concentration upon electronics inevitably brought its problems. In general I felt, particularly with the piano, that there was a danger of live electronics and tapes blurring and covering subtleties in the instrumental playing per se.

Of others we heard who failed to get past the first round, we took pleasure in the sunny disposition of Irish harpist Cliona Doris, who extended her solo performance at one of the lunchtime concerts with tinkling portable percussion to her left and right in R Murray Shafer's The Crown of Ariadne. Most bewildering for us was the fate of British mezzo Claire-Louise Lucas, who brought interpretative understanding of each composer in her first round session. She displayed impressive poise, steady tone and long legato phrasing in Ives The Housatonic at Stockbridge (a hard way to begin), a moving and disturbing intensity to Maw's Voice of Love (both supported in perfect unity by her composer-pianist partner Jonathan Darnborough), and end a well balanced short programme with a devastating musico-theatrical depiction of the incredibly difficult split-second changes of mood and expression which tumble over each other in Berio's seminal Sequenza III. It was the finest account of this 1967 masterwork I had encountered since those of Cathy Berberian herself.

Duos and Ensembles

None of the competing duos or ensembles reached the finals, and their members must have wondered whether they had entered the wrong competition. For some of them the problem was not performance quality but repertoire; we learned that for this jury an important criterion for this first competition in a new century had been the inclusion of really new music. We had enjoyed the Lutoslawski Quartet, who appeared in formal evening concert rig and followed W. Lemanski's Miniatura of 1995 (a close relation to Barber's famous Adagio) by subverting all convention with gusto in Penderecki's hilarious and anarchic, if now dated, String Quartet No 2 of 1968.

We were impressed by New Noise, especially in Birtwistle's Pulse Sampler, for which percussionist Jobey Burgess knelt on a prayer mat before his oboist partner Janey Miller, and by new possibilities for the humble recorder trio as demonstrated by Les trois en bloc in David Lesser's Discourses Inscribed in Air.

Most innovative in our opinion was the flute, percussion and electro-acoustic harp Trio Controverse from Montpelier (nearly a quartet, harpist Sabien Canton's new baby being close to arrival!). Their programmes were predominantly French, with Alain Louvier's Paysages the best demonstration of the enormous potential of this line-up. They would have been our choice for the special electronics prize. Allowances have to be made for these unusual combinations; quality new works by fine composers are as yet in short supply.

Definitely Different

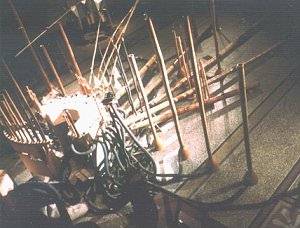

At Laurenskerk, a magnificent church of cathedral dimensions devastated in

1940 (fully restored and now linked with those cathedrals destroyed at Dresden

and Coventry) the organist Willem Tanke shared a concert with a difference

with Hans van Joolwijk's bambuso sonoro installation. This

is a musical sculpture, a cross between an octopus with curly flexible intestinal

tubes and an interpretation of the inner workings of an organ, its pipes

made of bamboo stems from smallest to as large as a tree. In the middle of

this fantastical construction, the sculptor-composer produced a happening

of esoteric sounds, looking like some wonderfully weird professor in control

of a crazy creature with a life of its own; an antidote to the more

conventionally wonderful sounds of the Great Organ, and the attractive smaller

one from which items were contributed by organ students from the Conservatoire.

An improvised Duel with Willem Tanke was less convincing than the

premiere of Vanishing Points by Roderik de Man, with live electronics

complementing the full organ to dramatic effect.

One of the evening concerts demonstrated some of the latest 'no-touch' finger sensor techniques. We had in the past experienced earlier experiments by Michel Waisvisz in this recondite developing field, which created a sensation in London's Almeida Festival long ago, and more recently other demonstrations in concerts at the South London Art Gallery in association with Unknown Public. On this occasion Wilco Botermans on the now ancient Theremin, which dates back to 1920, was joined for his Cause Without a Rebel by accordionist Eric de Reijer in forty minutes of avant-garde bizzarerie.

Another music installation enlivened the reception/café space in the

Conservatory during the week. Cantan un Huevo by Peter Bosch

and Simone Simons is a jolly collection of green bottles on bed springs

which bounced and clattered away merrily for a few minutes whenever the

computerised control was switched on by passers-by.

Master Classes

After a full day completing first stage adjudication, the five jurors gave simultaneous master classes for all comers. Commuting as listeners between five studios, we heard Melvyn Poore introduce novices to hands-on live electronic manipulation of tuba and bass clarinet tones at a basic level; his approach relaxing and unthreatening for the participants, if a little tentative for listeners. Dutch pianist Ton Hartsuiker reassured players that a piece which felt too long probably was so; the composer should reconsider it! Innovative composer/cellist Frances-Marie Uitti, long resident in Holland, explained how her two-bows technique was developed to bring a range of harmonic possibilities into working with four strings. She urged two young string players to 'stay stock still - don't move your body - get all the expression in your fingers', and to concentrate on intonation and maintaining real bow contact with the strings at all times. Working on a 'kitsch' solo, she wanted violinist Lynn Bechtold to play a passage in many different ways, and we heard the benefits of this approach at a lunchtime concert afterwards. Ms Uitti described the revelatory experience of working thus for four hours with Kurtag on a tiny 1½ min melody, 'play with the instrument, have fun, there are no mistakes, everything is good.'

Pauline Oliveros helped an accordionist to make his piece 'more living' by exploring strap adjustment and advising him not to be slavishly preoccupied with dynamics, 'let the sonority live - observe dynamics but not to the extent of losing tone - don't lose energy'. In conversation she discussed her beliefs as a composer (she had won the Gaudeamus Composers Competition in 1962) - all her music now has a built-in creative role for the performer, she seeks 'to create community rather than career' and has 'a problem with competitions, which create losers', and she would like Gaudeamus and other organisers to build into their competition rules 'more gender balance' in the compositions to be offered. American guitarist David Starobin voiced his concerns about competitions to a group sitting on the floor at his feet. He offered sensible and helpful advice about life and careers in music, emphasising that competitions are not what real musical life is all about. He assured them that shooting stars can as quickly fall, and that there are ways of making a contribution and advancing a career in music even if you don't win a competition.

Competitions for the 21st Century

Pauline Oliveros and David Starobin had struck chords that we found pervasive in informal conversation with participants; the whole issue of competition ethos, oft debated, was rehearsed yet again. Does a competition of this type perpetuate an unhealthy climate of competitive one-upmanship and self-centred individualism; a 'me-me-me' culture rooted in now bygone centuries? The Rotterdam design ensured that there must be as high a proportion of 'losers' as in any lottery, but the emotional stakes are higher. Perhaps one positive effect of competitions is to help aspirants to harden themselves against the realities of one of the most demanding of all professions; all are bound to suffer knock-backs sooner or later, and those who have had an easy passage can suffer more when things do not go their way.

The jury too is bound to 'lose', having the unenviable task of judging between such extreme unlikes, and obliged to deliver more disappointment than comfort and encouragement. The resultant feelings of real anguish and utter dejection, conveyed openly by some, tended to mar an important part of the exercise for both performers and listeners, the celebration of the pleasure to be had from music-making and from achieving a good performance upon its own terms, not necessarily coinciding with the parameters set by the judges. We gathered that there had been uncertainty about the criteria being applied, and that some who were eliminated early felt thwarted in the first round by not having had an opportunity to present themselves at their best in any prepared items of their own choice, and that this might have jeopardised their chances to advance through the stages.

The competition rules state, starkly but sensibly, 'the verdict of the jury is not subject to debate', but there was clearly a need for everyone to receive automatically sympathetic support and advice, with feedback about unsuccessful programmes and their delivery. Perhaps the organisers might weigh those aspects alongside the heavy demands put upon the jurors to perform in the Jury-Members Concert during the week and also to conduct Master Classes?

For English competition watchers, comparison with the London scene has been thought-provoking. Seen&Heard has reported recently on the British Contemporary Piano Competition, the World Piano Competition , the 8th International String Quartet Competition, the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition and, this year and last, the annual weeks of Park Lane GroupYoung Musicians 2001 2000, which carry no money prizes.

There are no easy answers to the conundrums regularly raised by competitions. But at times in Rotterdam we felt that perhaps the experience of exposure before the audience in this prestigious Dutch event could be sufficient prize for taking part? Listeners, professional and amateur alike, could thereby be encouraged to make their own connections with the musicians and their varied instruments and styles of playing. That could make for a less gladiatorial contest, with more enjoyment and less 'thumbs down', at no cost to maintaining critical judgement.

As for standards of performance and presentation, we have found these very similar at all those differently patterned events we have attended, and anticipate that whilst competitions are with us for the foreseeable future, their diversity will continue and aspiring musicians should be able to find events to enter which will best suit themselves.

Spare time

Rotterdam is not a conventionally picturesque city so it cannot feed off

the historical charms of a by-gone age like so many other Dutch towns. However,

while strolling around we came across many striking contemporary buildings

which assert themselves boldly as being of the here and now, including two

magnificent bridges at the port. Despite being a vibrant commercial centre,

traffic density seems to be low, no doubt due to the excellent public transport

system. The only queues of cars we encountered were on some evenings, for

multi-storing parking and a night out in town.

For non-musical aesthetic nourishment there is the world-class Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum and the Kunsthal. We had little time to assess the smaller venues for the visual arts. Nor should gastronomic delights be ignored. It is possible to eat well, and - comparing like with like - much more cheaply than in UK and we regaled ourselves at some excellent Chinese and Indonesian restaurants.

The De Doelen concert halls and conference complex, one of the cultural

gems of the city, opened in 1966 and are still looking and

sounding as good as any of the best we have encountered

in Europe. The well-proportioned Grote Zaal has superb acoustics, but we

found the medium sized Juriaanse Zaal a bit on the dry side. We did not sample

the attractive small recital room tucked into the middle of it

all.

as good as any of the best we have encountered

in Europe. The well-proportioned Grote Zaal has superb acoustics, but we

found the medium sized Juriaanse Zaal a bit on the dry side. We did not sample

the attractive small recital room tucked into the middle of it

all.

The public areas surrounding and connecting the performance spaces

are vast, beautifully lit and with plenty of seating; a really inviting and

visually interesting place to sit in and wander around.

During our week in Rotterdam we took in two prestigious concerts in the Grote Zaal. Peter Donohoe gave there a fine account of Bartok's 3rd piano concerto with the excellent Radio Philharmonic Orchestra under Claus-Peter Flor, [below] and enterprisingly framed by Janacek's Taras Bulba and Shostakovich's eccentric and untypically entertaining 9th Symphony. They all appeared to relish playing in a hall which separates and clarifies textures, making everything clearly audible. Earlier in the week, Sir Simon Rattle had a capacity audience there spellbound by Haydn's Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons) with the Nederlands Kamerkoor of about thirty singers and Frans Bruggen's Orkest van de Achttiende Eeuw. The soloists Christiane Oelze, John Mark Ainsley and David Wilson Johnson were ideal, and afterwards there were prolonged, fully deserved standing ovations for all concerned. This was a performance for the 21st century, using 'authentic' instruments and historically informed playing style, but with infinite subtleties of expression unlikely to have been possible, or even sought, in the 18th C, every detail of which told with clarity in this large state-of-the-acoustic-art modern auditorium.

Peter & Alexa Woolf

Appendix: List of Repertoire offered by those participants in the International Gaudeamus Interpreters Competition 2001 who were heard by Seen&Heard.

The full list can be obtained from Gaudeamus, Swammerdamstraat 38, 1091 RV

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, tel.: 31-20-6947349, fax.: 6947258,

info@gaudeamus.nl,

www.gaudeamus.nl and the Dutch compositions

can be ordered from Donemus, Amsterdam or, in UK, from Novello & Co.

(tel: 071- 287-6329).

Tony Arnold Voice United States 1966 03

Thomas Ades Life Story 1993 7'

Georges Aperghis Recitations 9 & 10b 1978 7'

Robert Heppener Four Songs on Poems by Ezra Pound 1970 14'

Oliver Knussen Whitman Settings 1991 11'

György Kurtag Requiem for the Beloved 1986 6'

György Ligeti Weores Songs 1947 6'

Olivier Messiaen Poèmes pour Mi, book 1 1936 13'

Klas Torstensson Urban Solo II 1991 7'

Lynn Bechtold Violin United States 1972 04

Gene Carl Scratch 1985 6'

Philip Glass Strung Out for amplified violin 1967 18'

John Harbison Four Songs of Solitude 1985 15'

Lei Liang Feng 1998 4'

Alvin Lucier new work 2000 10'

Otto Luening Gargoyles for violin and tape 1960 8'

David Clark Little Stonehenge Study 8 1986 6'

Dmitri Shostakovich Three Pieces 1940 8'

Sarah Bob Piano United States 1974 05

Curtis K. Hughes Avoidance Tactics #1 (electronic version) 2000 11'

Lee Hyla Third Party 1998 5'

Vanessa Lann Inner Piece 1994 8'

Claude Vivier Shiraz 1977 14'

Simeon ten Holt Soloduiveldans III 1990 14'

Karlheinz Stockhausen Klavierstück V 1954 8'

Winston Choi PianoChina / Canada 1977 11

Brian Ferneyhough Lemma-Icon-Epigram 1982 14'

Ton de Leeuw Les Adieux 1988 18'

Mischa Zupko Etudes for Piano 1997-2000 14'

Joep Straesser Just Signals 1982 13'

Charles Ives Sonata No. 2, 2nd movement: Hawthorne 1911-20 9'

Joji Yuasa Cosmos Haptic II - Transfiguration 1986 12'

Iannis Xenakis Mists 1980 14'

Frédéric Daumas Vibraphone France 1973 13

Daniel Almada Linde (tape - CD) 1994 8'

Edmund Campion Losing Touch (with tape - ADAT) 1994 12'

Edison Denisov Nuages Noirs 1984 10'

Franco Donatoni Omar II 1985 9'

Norio Fukushi Gray of gray 1987 12'

Philippe Manoury Solo livre des claviers 1988 8'

Meeuwis Rebel Vibrafoon solo 1979 4'

Willem Vries de Robbe Distant chimes / Clear Day 1978 5'

Cliona Doris Concert Harp Northern Ireland 1970 14

Javier Alvarez, 1956 Acuerdos por Diferencia (for harp and tape) 1989

12'

Donnacha Dennehy Curves (for amplified harp and tape) 1996 9'

Willem Jeths Vertooning 1997 12'

Keyla Orozco Arpa 1998 6'

R. Murray Schafer The Crown of Ariadne for solo harp

with percussion and tape 1982 25'

Toru Takemitsu Stanza II for harp and tape 1971 10'

Ian Wilson in blue sea or sky 2000 10'

Marcel Tournier Etude de concert: au matin 1940 4'

Karin De Fleyt Flute Belgium 1972 19

Rudolf Escher Monologue for flute 1969 9'

Jan van Vlijmen Against that time (solo IV) 1995 18'

Karlheinz Stockhausen Flautina 1989 6'

Brian Ferneyhough Cassandera's Dream Song 1970 9'

Salvatore Sciarrino L' Orizzonte luminoso di Aton 1989 xx'

Karlheinz Stockhausen Flöte aus Orchester-Finalisten,

flöte und Elektronische Musik 1995-96 6'

Kaija Saariaho Laconisme de l'aile 1982 9'

Aleksander Gabrys Double bass Poland 1974 20

John Cage 59 1/2 seconds for a string-player 1960 1'

Jacob Druckman Valentine 1969 10'

Ron Ford High Rise 1987 6'

Aleksander Gabrys Bas-el-Karneval (+ electronics) 2000 10'

Ryszard Gabrys An die Freude 1998 6'

Vinko Globokar Dialog über Feuer (+ electronics) 1994 13'

Walter Hekster Five Images 1981 8'

Thomas Kessler Kontrabass Kontrol (+ electronics) 2000 9'

Giacinto Scelsi C'est bien la nuit 1988 3'

Yoshio Uchimoto Raga in melancholy 1995 12'

Iannis Xenakis Theraps (+ electronics) 1976 12'

Jorge Isaac Recorder Venezuela 1974 32

Louis Andriessen Ende 1981 3'

Moritz Eggert Außer Atem 1994 9'

Luciano Berio Gesti 1966 5'

Rolf Riehm Weeds in Ophelia's Hair (+ amplification) 1991 10'

Giorgio Tedde Austro 1991 10'

Fabrizio de Rossi Re Salse (+ tape & live electronics) 1993 14'

Timucin Sahin new work (double bass recorder,

computer & live electronics) 2001 11'

Mauricio Kagel Atem (+ tape & live electronics) 1969-70 15'

Roderik de Man Entanglement (+ tape) 1987-91 10'

Veli Kujala Accordion Finland 1976 38

Ton de Leeuw Modal Music 1978-79 12'

Henk Badings Sonata 1981 14'

Jouni Kaipainen Gena 1987 10'

Vesa Valkama Tyy 1997 4'

Arne Nordheim Flashing 1986 6'

Mauricio Kagel Episoden, Figuren 1993 12'

György Ligeti Hungarian Rock 1978 5'

Toshio Hosokawa Melodia 1979 8'

Aram Chatschaturjan Toccata 1932 5'

Claire-Louise Lucas Mezzo-soprano United Kingdom 1965 41

Jonathan Darnborough Calefieri for voice & tape, 1996-98 7'

Vanessa Lann Herman's Song 1994 12'

Alison Bauld The Witches' Song 1990 4'

Simon Emmerson Time Past IV for voice & tape 1984 12'

John Tavener 3 Surrealist Songs for mezzo, tape & piano

(doubling bongos) 1968 9'

Ton de Leeuw Vocalise 1968 3'

Luciano Berio Sequenza III 1967 7'

Nicholas Maw The Voice of Love (2, 3 & 4) 1966 10'

John Cage The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs 1942 3'

Charles Ives The Housatonic at Stockbridge 1910 3

Monika Mattiesen Flute Estonia 1966 42

Ton de Leeuw Reversed Night (solo flute) 1971 11'

Robin de Raaff Contradictie I (solo flute) 1994 7'

Steve Reich Vermont Counterpoint

(flute/alto/piccolo + tape) 1982 10'

Kaija Saariaho Noa Noa (flute + live electronics) 1992 10'

Kaija Saariaho Laconisme de l'aile (flute + live electronics) 1982

9'

Luciano Berio Sequenza (solo flute) 1958 7'

Ivan Fedele Donacis ambra (flute + live electronics) 1997 12'

Toru Takemitsu Itinerant (solo flute) 1989 6'

Pierre Jodlowski Dialog/No Dialog (flute/alto + live electronics) 1997

14'

Edgar Varese Density 21.5 1936 4'

Snezana Nesic Accordion Yugoslavia 1972 45

Joep Straesser from 'Fresh Air': I. Sonata piccola, II. Fantasia 1991

9'

Nikolaas van Straten Sonatine nr. 2 19xx 5'

Aho Kalevi Black Birds (Sonata no. 2) 1997 19'

Snezana Nesic Fünf Visionen von Pierre Abälar 2000 22'

Sofia Gubaidulina De Profundis 1978 12'

Mauricio Kagel from 'Rrrr...' I. Raga, II. Rossignols enrhumés,

III. Ragtime Waltz 19xx 8'

Olivier Messiaen Meditation no. 7 19xx 2'

Sarah Nicoll Piano United Kingdom 1974 46

David Sawer The Melancholy of Departure 1990 13'

Jonathan Cole Trapdoor 1999 8'

Stuart Macrae Piano Sonata 1998 18'

Karlheinz Stockhausen Klavierstück IX 1954-61 11'

Rudi M. van Dijk Sonatina 1951 4'

Caroline Ansink Greener Grass 1987 8'

Leos Janacek Sonata 1905 11'

Heather O'Donnell Piano United States 1973 47

Charles Ives 'Hawthorne' from Piano Sonata no.

2, Concord, Mass., 1840-1860 1912 13'

Ulrich Leyendecker 13 Bagatellen für Klavier 1989 7'

Tristan Murail Cloches d'adieu, et un sourire..., 1992 5'

Theo Loevendie Strides 1976 8'

György Ligeti Etudes pour piano: no. 6: Automne à Varsovie

1985 5'

Jonathan Harvey Tombeau de Messiaen for piano and

digital audio tape 1994 9'

Rob Zuidam Ground 1985 5'

Gerald Barry Triorchic Blues 1991 4'

Olivier Schneller Coulds 1997 6'

New Noise Duo: oboe & percus. United Kingdom 70

Janey Miller, oboe/Joby Burgess, percussion

William Attwood Pascal's Dungeon 1999 10'

Floris van Bergeijk new work 2001 9'

Harrison Birtwistle Pulse Sampler 1981 9'

Michael Finnissy Delal 1984-88 9'

Simon Holt Banshee 1994-96 11'

Nigel Osborne new work 2001 12'

Steve Reich Clapping Music 1967 4'

Iannis Xenakis Dmaathen 1976 11'

Duo Subiaco Duo: flute & piano The Netherlands / Bulgaria 73

Jacqueline van der Zwan (flute)/Ani Acramova (piano)

Theo Loevendie Music for flute and piano 1979 12'

Chiel Meijering Parrots in Tunesia 1979 8'

Lowell Liebermann Sonata 1987 14'

Sumire Nukina Tango for a Mother 1996 9'

Gerard Beljon Flow 1999 11'

Rudolf Escher Sonate 1976-79 16'

Don Banks Trio Trio: violin, horn, piano Australia / The Netherlands 74

Helen MacDougall, horn/Kees Hilhorst, viool/Aljosja Buijs, piano

Jasper Kloek La Melodia 2000 20'

André van Haren Trio I - mvmnts 1 & 2 1996 8'

Iain Matheson When Suddenly 1999 10'

Don Banks Trio 1962 15'

Leif Segerstam Episode no. 20 & 21 1983 9'

Lennox Berkeley Trio op. 44 1954 30'

Lutoslawski String Quartet String Quartet Poland 75

Emanuel Kamil Drzyzgula - violin/Michal Lisiewicz - violin/

Anna Szarek-Lisiewicz - cello/Joanna Ziobro - viola

Witold Lutoslawski String Quartet 1965 25'

Krzysztof Penderecki String Quartet no.2 1968 10'

Johannes Hildebrand Streichquartett n. 1 1997 8'

W. Lemanski Miniatura 1995 5'

Jan Rokus van Roosendael Drone 1993 10'

Caroline Ansink Shades of Silence 1985 10'

Les trois en bloc Recorder trio Germany 76

Barbara Engelmann, Susanne Rieman, Anja Wetzki

David Lesser Discourses Inscribed in Air 2000 11'

Violeta Dinescu au coeur du silence 1995 9'

Frans Geysen Digitaal - Analoog - Identiek 1986 3'

David Little Brain-Wave 1990 10'

Pèter Köszeghy Nausikaa 1999 11'

Witold Szalonek Haupt der Medusa I 1996 17'

Trio Controverse Trio: el. harp, percussion, flute France 78

Martine Flaissier, electro-acoustic harp, Philippe Limoge,

percussion, Henry Vaudé, flute

Alain Louvier 4 paysages (4 movements) 1998 20'

Thierry Escaich Psalmodie & Introït pour l'office des

ténèbres 1994-96 10'

Graciane Finzi Hommage à Aristarque de Samos 1995 10'

Vincent Paulet Le grand Stellaire (3 movements) 1992 10'

WIllem Jeths Brezza (flute & percussion) 1987 8'

Willem de Vries Robbé Skies and Birds (flute & percussion)

1983 6'

Return to:

Return to: