A short stay in Zurich made an opportunity to gain a varied impression of the presentations at the opera house in four evenings. We took in an innovative premiere of Berlioz, a revival of a distinguished Verdi production and a traditional presentation of an ever-favourite operetta, and were particularly pleased to hear some members of the opera orchestra in a chamber music concert.

La Damnation de Faust

Berlioz's

'dramatic legend' was not conceived for the theatre, so there is no traditional

visual representation to follow or to challenge. This made it more surprising

that the new production was greeted by boos for the director at Zurich Opera

House and controversy in critical responses; an example of entrenched

conservatism and 'produceritis', which has for so long dogged innovation

in opera (Tom Sutcliffe in Believing in Opera (Faber&Faber) -

"important - - required reading" (Max Loppert - Opera). Seeing Berlioz's

vast Faust conception confined behind a proscenium arch soon after reviewing

the

DVD

of the extravagant Salzburg production (and whilst still under

the spell of ENO's opening up of the whole interior of the London Coliseum

as a performing space for their Italian season) required initial adjustment

to a smaller scale, but the approach of the husband & wife team Erwin

Piplits (director) and Ulrike Kaufmann (design) quickly banished

thoughts of comparison. Original and newly thought out, their economical

staging was almost never distracting, indeed it seemed to help to concentrate

attention upon the astonishingly original music which Berlioz found to illustrate

these scenes from Goethe's Faust, adds to the expressivity of the musical

text and reveals the internal logic of this dramatic legend. The directness

and simplicity with which they distilled meaningful essences from the musical

drama and embodied them in visual terms act as counterpoints to a sound world

filled to the brim with significant musical events. It also helped with the

pacing of the score, e.g. making sense of the surprisingly extended Menuet

des Follets, a marvellous orchestral set-piece, but one which can seem

overlong in the context of concert performance. Throughout there were numerous

fleeting directorial touches, whose significance would become clearer and

fall into place with a second viewing - but the Opernhaus's higher pricing

since our last visit to Switzerland is likely to be prohibitive.

The drama is both literally and metaphorically enlightened also by Jurgen Hoffman with his brilliant lighting effects, which tell their story silently but with great artistry. With an intense orange glow spreading over the whole stage at the start he sets the reflective scene for Faust the loner, the outsider, easy prey to manipulative forces. As the orange glow gradually fades, the chorus is dramatically revealed through the haze of the orange curtain, its members standing in neat rows, dressed like a disciplined urban workforce. Harsh top-lighting produces sharp shadows on the ground and emphasises the importance of the chorus in the telling of this legend.

The slatted multi-purpose construction in and around which the action turns is a telling metaphor for the intertwining of the physical and meta-physical worlds; outward events being reflections of inward thoughts and struggles and vice versa. At times action is revealed through and behind it with diffused light, at others a soft red glow reveals the house as a retreat, as a refuge for Faust. Later, harsh, piercing white light arrows through the slats to express Marguerite's awakening to her abandonment

This Faust is not a world-weary academic or larger than life superman. He

is portrayed as a vulnerable, insecure, tormented and very ordinary young

man. When the crowd swirls around him, banner-waving in revolutionary fervour,

he stands apart and still, unable to get involved and to 'follow- my- leader'.

He cannot find comfort in a retreat into his intellectual world. A harsh

white light on his large open book reveals blank pages. There are no answers

to his searching questions. He is easy to empathise and identify with as

sung by mellifluous lyric tenor Zoran Todorovich with intensity and

stamina, and tone which never hardens. The shadowy figure of Mephistopheles

is all too credible, presented in ordinary attire as the reasonable tempter,

someone strong; plausible, experienced and easy to lean on at a time of distress.

This Mephisto, powerfully rendered by Egils Silins, bursts out of

the curtain in Faust's study during his crisis point. Although surrounded

by a circle of sulphurous green light as a warning (to us) he is easy to

fall for, at your peril.

Liliane Nikiteanu, the expressive mezzo-soprano, was given the most

interesting and complex characterisation as Marguerite in this production,

which is likely to develop during the run. We meet her as a young girl,

sleepwalking perhaps, waking out of uncomfortable dreams, comforting herself

with little exercises and childhood play, and slipping back into an erotic

dreamworld. She expresses her longing for love, illusion of satisfaction

followed by disappointment and despair, a total psychotic breakdown signalled

by folding into herself in a foetal position and twitching; all that conveyed

with moving conviction. In accord with this conception it seemed at the

première that the King of Thule ballad may have deliberately

been given an offhand, low key treatment (its echo on cor anglais

was notably more plangent), but her love scene with Faust rose to rich intensity

and prepared us, after a chilling Ride to the Abyss, for a visually simple

final apotheosis, which avoided any mawkishness, Marguerite standing alone

in a hieratic pose whilst the Zurich Opera's state-of-the-art sound system

suffused the entire auditorium with a magical choral surround-sound.

We are all too apt in England to be self-congratulatory, readily believing ourselves to have special understanding and authority of Berlioz - Sir Colin Davis - (and Janacek - Sir Charles Mackerras). The French conductor Phillipe Augin (brought from Hamburg to replace an injured Christoph von Dohnanyi) had nothing to fear from comparison, nor did the Zurich Opera House Orchestra and Chorus (augmented with the Swiss Chamber Choir and shrieking children) from memories of the LSO forces in Davis's Berlioz Odyssey 2000 just finished in London. Augin's interpretation lacked nothing in excitement of the set pieces but emphasised more Berlioz's delicacy of scoring, and the marvellous acoustics permitted the singers to remain perfectly audible and clear in the p to pp range. Although Sir Colin favours concert performances of Berlioz operas as being ' - - not subject to the vagaries of what is happening on stage - - or the obstacle of perverse productions' (programme of The Trojans in London), Zurich's presentation fully vindicated a still controversial view that La Damnation de Faust is best Seen and Heard in the theatre.

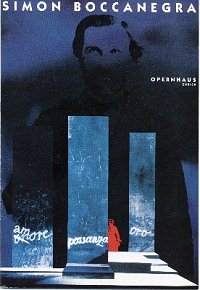

Simon Boccanegra

Opera has always thrived on crises, which generate legends. After a successful

dress rehearsal, the eponymous protagonist at Zurich awoke with a severe

cold on the morning of this revival of Marco Arturo Morelli's 1995

production of Simon Boccanegra, unable to sing. A famous baritone

was borrowed from Munich on the day for just the one performance, and Paolo

Gavanelli stepped into the role of Doge of Genoa as if he had grown into

this production alongside his colleagues; a strong team which demonstrated

the present excellent health of Zurich opera.

Apart from resplendent singing and convincing acting by every singer listed above, the particular privilege and joy of this evening was the opportunity to savour (and watch, from over the orchestra) the veteran conductor Nello Santi (who has been coming to Zurich for 43 years) conduct Verdi's marvellous middle-period masterwork without a score. The orchestra loves him, and responded to every nuance of dynamics and rubato; Santi's left hand was continually fluttering to quieten the tone, allowing the singers to exploit the p and pp ranges of their voices in this sombre masterpiece, which begins by establishing the hostility between baritone Boccenegra & Fiesco (sonorous bass Laszlo Polgar) which persists for twenty five years until final resolution at the end. Under Santi's ever watchful and alert eye, the marvels of Verdi's often dark orchestral colours emerged newly painted. It was extraordinary to recall that when one of us reviewed the first performance in UK of Simon Boccanegra (Sadlers' Wells, early '50s) only a handful of Verdi operas were familiar in England.

Morelli's simple, unclutterd staging, all in sombre dark blues and greys, took its cue from the grandiose towers conspicuous in parts of Italy, built to symbolise wealth and power. The tall windowless blocks are devoid of signs of ordinary life and display a bleak, masculine might. Amelia (Miriam Gauci), the only female vocal presence, dressed in yellows and orange, with flaming red hair, is the radiant element, the sun, warming this dark space of power struggles and intrigues. She is the real and still centre of this opera. All strands move through her, because of her and for her.

The focus of the staging was always upon the tensions between the protagonists, with no directorial distraction to deflect attention from their singing. No attempt was made to indicate ageing with the passage of time after the prologue. The knotted story is not easy to grasp, even after repeated reading of the English synopsis which was thoughtfully provided. Even Italian speakers in the tri-lingual Swiss audience would have been helped by sur-titles, which have apparently not yet reached Zurich.

The complex actions and interactions between the characters have a social and political dimension. There is an intertwining of personal ambitions with revolutionary aspirations. This opera was written in 1857, after the turmoils of the 1848 upheavals and the failure (for a time) to achieve a unified state. The work is propelled forward towards tragedy on a stream of misunderstandings leading to unexpected and unwanted events. A lack of trust, and unwillingness to share knowledge, to be open, as well as naked manipulation for calculated egotistical reasons, creates havoc and pain, but there are also some hopeful pointers, with the reconciliation of the bitter opponents and the marriage of the young couple, a symbol for a better future.

Although Verdi revised this work heavily some 25 years later, its basis remains in a real lived experience of a particular social and political reality. Verdi's ability to be in touch with the deepest social currents, to be in tune with his time, never fails to astonish, but there are elements which transcend the specificity of his situation and still speak to us. A gamut of human emotions runs through this work from love, hate, revenge, joy, pride, fear, pity and courage, to sadness and ultimate forgiveness.

This production at the Zurich Opernhaus displays not only a high standard of musical integrity but also respect for the gripping emotional and intellectual content of Simon Boccanegra.

The Merry Widow

Lehar's operetta is one of those staples, which every European opera

house feels bound to re-cycle regularly - to balance the books and satisfy

its more conservative clientele. It is a Ruritanian fantasy about beautifully

costumed folk living in Paris; a thin little story about money, class, marriage

and the irresistible attraction of a wealthy, glamorous banker's widow, with

a Balkan community keen to keep the inherited hundreds of million francs

from passing into French hands. The worlds of banking and ostentatious indulgence

seemed to be just the thing for Christmastide corporate entertaining in Zurich;

two different routes through to our press seats, high over the orchestra,

were assiduously guarded and barred until nearly curtain-up, to avoid disturbing

a pre-show party.

The evening depended upon Noëmi Nadelmann as Hanna Glawari, and she had a fine repertoire of commanding gesture, with occasional petulance, and singing fully equal to bringing off the famous songs; a real star performance. Her Danilo (Peter Weber) was adequate, and improved during the evening, but Ute Gfrerer was shrill as Valencienne and the rest of the cast were individually unmemorable. The intricate stage movements of the large cast were well marshalled and the general effect was one of sumptuous kitsch, no doubt nostalgic of imaginary good old days for the very oldest members of the audience.

The orchestra, so admired in two other productions, seemed to be having an off-night after the concentration needed to give of their best in Berlioz and Verdi. Maybe Günter Neuhold failed to command the respect given to Nello Santi, or was it just that Lehar's scoring is crude by comparison with Verdi & Berlioz? (Probably an unwarranted assumption - there are many recordings with distinguished conductors to check it against.) They began loud and rough, with trombones rather too prominent; the hit-tunes were usually shadowed by a cushion of violins in unison with the singers; only a love duet towards the end had an individual touch with an attractive cello obligatto. Synchronisation between pit & stage was sometimes imprecise.

Probably such carping strictures are inappropriate for such a show; a jolly festive romp, with the course of true love far from smooth, but a happy ending guaranteed. There were parties by day and night at the eponymous heroine's lavish residence with dancing and a roisterous can-can by girls from Maxims, which predictably brought the house down. The staging was thoroughly traditional, probably similar to that of the 1905 première - and who would have it different?

[My confidence in our judgement was fortified by the serendipitous arrival of a DVD of the Zurich production of Offenbach's La Belle Helene, awaiting us upon our return from Switzerland. Under Nicholas Harnoncourt's needle-sharp direction - combining precision with just the right lilting rubato - left no doubt that Zurich has a great opera orchestra (see also S&H's review of their Cosi together.)

This DVD (Arthaus 100 086) review is a real joy, and just the thing for spending any spare record tokens at the New Year; brilliant staging, lighting and video photography, equally so the acting and singing by a splendid cast including the versatile Liliana Nikiteanu (Marguerite in our Faust) and headed by the jolie-laide Vessalina Kasarova, a sparkling mezzo who extracted maximum fun as the most beautiful woman in the world.]

Opera Nova Ensemble Concert

This appearance by five members of the Zurich Opera Orchestra - David Bruchez (trombone and sackbut) Christine Theus (cello & baroque cello) Jean-Jacques Dünki (piano & harpsichord) Heinrich Mätzener (bass clarinet) Hanspeter Achberger (percussion) - was part of an innovative series which began in 1991 with the formation of a flexible ensemble to play a variety of chamber music. On this occasion the trombone of David Bruchez was featured in various combinations with clarinet, cello, keyboards & percussion. All members of the group play early music as well as the contemporary repertoire in which they specialise, and opportunities were taken to include items from 17 & 18 C, with sackbut and continuo, in proper period style. Has the age of super-specialisation begun to pass?

David Bruchez gave a well planned demonstration of the expressive scope of his instrument(s). The Choral, cadence et fugato by the elder Dutilleux (1916-79), a 1959 set-piece for the Paris Conservatoire, needs a powerful pianist to bring it off successfully as here at Zurich, and Jean-Jacques Dünki showed himself well equal to the requisite balance of forces - the trombone can easily overwhelm the piano. Bruchez throughout the evening demonstrated the dynamic range of both his instruments which can achieve expressive quiet playing, nowhere more so than in Valentin Marti's 1999 Rainshadows, a study in blend as against individualism, in delicate, evocative pianissimo, several of the players deploying rainsticks as well as their own instruments. With muted trombone and a reticent bass clarinet, there were cello whisperings close to the bridge, and an imposing battery of percussion was played with chopsticks (?) and fingers, bringing to mind earlier masters of quietude (Webern, Feldman) as well as Takemitzu's water pictures and also his father's muted Correspondance (... à la sourdine).. This six minute piece by the Zurich-based son of established Swiss composer Heinz Marti could find a welcome place as an oasis of quiet in a more strenuous contemporary music concert.

Jean-François Michel's Hommage to the sculptor Jean Tinguely traversed similar ground to Berio's in his popular solo trombone Sequenza, with - it has to be said - less originality. The American Stephen Rush (b.1958) provided a rousing conclusion to the evening, his youthful Rebellion of 1983 challenging the extrovert, flamboyant side of the trombone's personality with virtuoso attacks on the piano keyboard (with arm clusters and shouts) and a drumming cannonade on tom-toms and bass drum, all held in skilful balance by clever scoring.

Alexa & Peter Woolf

Return to:

Return to: