S&H Concert Review

Leipzig Gewandhaus: 8 December 1855

BEETHOVEN Emperor Concerto,

MOZART Arias from Figaro,

SCHUMANN Introduction and Allegro

Appassionato; Symphony no.2 Orchestra of the Age of

Enlightenment/Mackerras with Robert Levin (pianoforte) ) Nuccia Focile (soprano)

James Rutherford (baritone) Queen Elizabeth Hall, 23 January 2001

|

|

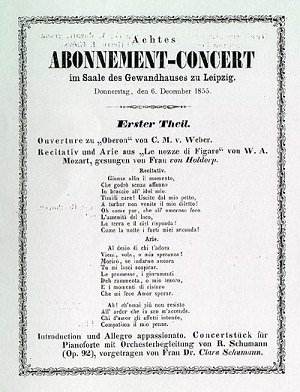

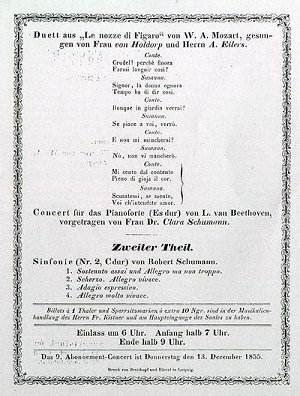

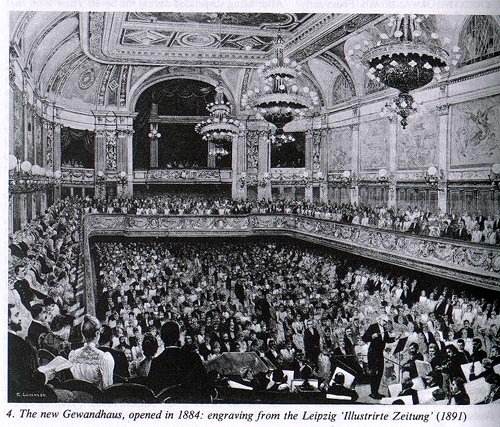

A recreation of a mammoth concert given in the Leipzig Gewandhaus (Clothiers' Hall) as a triple-decker programme (nearly three hours with intervals) was a tempting prospect, heightened by the sight of a very beautiful Streicher piano on stage, upon which after the customary Overture (Weber's Oberon) Robert Levin played the Schumann Introduction and Allegro Appassionato. From an allocated seat in the middle of the QEH, however, it sounded distinctly muted and liable to be covered even when only a few orchestral instruments were involved. One wondered how this music would have sounded in the original Gewandhaus to its 1855 audience, with its wooden walls, floor and ceiling, splendid acoustics and uninterrupted views for the audience in serried ranks at right angles to the platform, women in the front rows facing each other - 'the women staring at each others' dresses and the men staring at each other' according to a contemporary account.

The QEH is really quite the wrong hall for this sort of historical reconstruction exercise, and the programme had no great coherence for modern tastes. Nuccia Focile had little time to relax into Al desio (a more florid aria which replaced Deh vieni when another singer replaced Nancy Storace, who was no longer available as Susanna in 1789 - interesting to hear, but not a patch on that imperishable favourite). The quasi-amorous duet Crudel! perche finora went better later in the evening, Focile persuasive in leading along James Rutherford's Count in his brief sole appearance.

Clara Schumann was keen that her husband advanced his reputation by major symphonic works, but the dark 2nd Symphony has always seemed to me the ugly duckling of the four, its strenuous first movement 'capricious and refractory' according to the composer, but possibly also reflecting Robert's depression in 1845. The scherzo was fast driven and there was a forced energy in Sir Charles Mackerras's finale, ending with 'an optimism that has not been easily won' (John Warrack). Only the adagio esspressivo was an oasis of relaxation. There was no particular revelation in Mackerras's account with a period instrument orchestra of Schumann 2, and one realised how CDs can foster unreasonable expectations of technical perfection. There were several roughnesses and cracked notes from the perilous natural horns, to remind us how commonplace those accidents were on the still notoriously treacherous valved horns not so many decades ago.

Best of all was the Emperor concerto, certainly so from a front seat near to the tail of the unframed 1847 piano (only two iron bars over the unvarnished soundboard). Beethoven seemed more skilful in allowing the soloist his head than Schumann, with well judged instrumentation in the tuttis. I liked Robert Levin's continuing to play through the long initial ritornello after signing in at the outset with his opening flourishes as a call to attention - no doubt normal practice in those days. I cannot vouch for how it all sounded far away at the back, and the forest of microphones made clear again how totally different is a live concert from CD or broadcast of the same music. That this event was not an unqualified success was a demonstration that the right auditorium, for both atmosphere and acoustics, is a key ingredient in the mix.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Seen&Heard is part of Music on the Web(UK) Webmaster: Len Mullenger Len@musicweb-international.com

Return to: Seen&Heard Index

Return to:

Music on the Web

Return to:

Music on the Web