Sokolov, Vogt, Volodos & Alperin with other pianists and keyboard players at Piano 2001 KKL Concert Hall, Lucerne 20-25 November 2001

Pletnev at Tonhalle, Zurich 26 November 2001(PGW)

Lucerne's late autumn annual festival is dedicated to the piano and to showing to what advantage it can be heard in the new KKL Concert Hall, which provides the possibility for acoustical tuning of the auditorium to each artist's own preference by adjustments to the reflective canopy over the stage and to the reverberation chamber's doors, a speciality of ARTEC. For musicians, numerous testimonials describe the rare pleasure of being able to hear their own playing very much as it sounds to the audience, which makes them eager to return to Lucerne. During the week I took the opportunity to sample seating positions in many parts of the hall, right up to the high fourth gallery. It is good for listening everywhere, with absolute clarity and projection of the quietest pianissimo, but I found the best sound towards the centre at each level.Soon after revelling in Mikhail Pletnev's unforgettable concert with Beethoven's concertos Nos 2 & 4, the prospect of hearing the same pairing of concertos played on instruments of the times to open the Lucerne November festival was inviting, though anticipated not without qualms. By way of light-weight overture (Dohnanyi & the Philharmonia had given Strauss' Metamorphosen to begin their London Beethoven cycle with Pletnev) a short sequence of nine dances put together by Franz Bruggen showed off the 'authentic' colours deployed by the London-based Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Bruggen naturally featured the little Contredance which so pleased Beethoven that he went on to use it in the Eroica and two other major works. A small natural horn held with the right hand alone, gave special pleasure, and one marvelled again at the silent ambience of the KKL Concert Hall, which enhanced all the timbres on display. But from then on, this proved to be an ill-advised opening concert for an important festival.

For many people the piano is a sticking point in general acceptance of period instruments. In contrast with violins from the age of Stradivarius, ancient pianos deteriorate and never improve with time. But numerous convincing demonstrations of how much had been lost because of the ubiquity of the powerful modern Steinway are available in recital and on CD, whether on restored originals or modern copies. Concertos are usually more problematic, and the disparity between a fortepiano's fragile tone and low dynamic level and that of an orchestra can be a shock. The 'best concert hall in the world' can do little to compensate for dull music making and Beethoven's (actual) first concerto was dismally disappointing as played through by Stanley Hoogland on the modern copy of a Walther fortepiano (Paul McNulty, Amsterdam), which he chose to bring from his own collection in the Netherlands. It was a straightforward and fluent run-through, Hoogland's eyes glued to the music, but there was no fruitful meeting with Bruggen's stolid accompaniment, no sparks between them, and no sign of any joint interpretative decisions having been made. The forest of close microphones indicated that radio listeners at home would have had a better bargain, but even so this account of a delightful and innovative concerto would have made few converts to the cause. The G major concerto No.4 fared a little better, on a slightly later Bohm instrument, which had sturdy legs and a more robust tone. It occurred to me that the famous and unique dialogue - 'Orpheus taming the Furies' (Liszt) - of the slow movement, composed during a period in which there was particular 'emphasis on the lyrical' (Peter Benary in the Lucerne programme book), might have been conceived by Beethoven to make a positive point about the disparity of power between keyboard and the orchestra of the time? Unfortunately, as conducted by Bruggen there was no show of force in the orchestral contribution, which notably failed to generate any drama on this occasion.

Another Walther/McNulty fortepiano was heard to far better advantage in Lucerne based Ulricke-Verena Habel's [left] lecture-demonstration of historical keyboard instruments (clavichord, harpsichord and early piano) in the ideal setting of the smaller Marianischer Saal. Her examples gave us characterful playing on three characterful instruments, and perhaps next year she might be offered the opportunity to give a full recital? A set of Mozart variations, played through in groups on each of her instruments, spoke eloquently of how important it is for aspiring modern pianists to familiarise themselves with the touch and sound of instruments upon which the repertoire classics were composed. The Russian pianist Alexei Lubimov is one who performs and records on both historical and modern pianos, and in interview for Strictly Off the Record he told me that he believes doing so enriches his interpretations both ways. [See also Related Recordings at the end of this report]- - - - - - - - - - - - -

The main recitals of the festival were given on a Steinway piano and were variably satisfying. My personal appraisals do not reflect audience responses, which were appreciative throughout. Readers may find my headed list of Piano 2001 surprising, with an Evgeny Kissin relegated to the 'also rans'!

Radu Lupu sits comfortably, leaning back in an ordinary chair - too comfortably? Beethoven Op 90 was flaccid and effete, lacking any 'backbone'. Its relaxed finale is Schubertian, but that is not the whole story, and Lupu played it as if already giving a Schubert impromptu, one of which he arrived at as an encore.

The only justifications I could think of for the disinterment, rather than revival, of Georges Enescu's rambling 1924 piano sonata were the shared nationality of composer and interpreter, and that this dispiriting, seemingly improvisatory work (though we were assured it is tightly constructed, with detailed notated rubato) had been dedicated to a Swiss composer/pianist so long ago. Its inclusion now did a revered musician, and far from negligible composer a disservice. More on his pianistic home ground, Radu Lupu gave a convincing and well rounded account of Schubert's last A major sonata, but his recital as a whole was one of several disappointments in the festival. So was that of Denés Várjon, whose early Beethoven (Op 14/2 in G major) was sometimes over-pedalled and lacked period awareness. He was sometimes betrayed by his fleet and fluent fingers, leaving him little time to shape and differentiate particular phrases and to fully characterise each of Schumann's Carnaval procession of miniatures. Várjon included a welcome Lisztian Rhapsody by Dohnanyi, but Liszt himself fared less well in one of the Mephisto Waltzes, virtuoso technical prowess taking all the pianist's energy.

Varjon's recital provided one of the very few forward looking 'modern' work in the festival - Bartok's Elegy No. 2 Op 8b.Sz - of 1909, nearly a century ago! Here was a tantalising glimpse of the possibilities of the contemporary pianoforte, with resonances inside the instrument to be savoured in the clarity of the KKL acoustic, and many innovative harmonic and textural touches, notably a rolling bass, which together made memorable this seven minute piece.

Another exception to the prevailing conservatism, albeit again from the beginning of the last century, was Janacek's desolate and introspective In the Mists (1912) with which Lars Vogt [left] began his serious programme, confirming positive experiences of his artistry in London and in Lucerne during the summer. Next came an unfamiliar early sonata, Op.2 in F# Minor by the nineteen year old Brahms, which Vogt had also played in London earlier in the month; its unusual, often rhapsodic character better appreciated for being heard twice. At the Lucerne recital he completed the festival's generous representation of Schumann's major works with the great Fantasy Op.17, its grave conclusion possibly having never sounded more beautiful before a large audience than in the KKL Concert Hall on this Sunday morning. For his single quiet encore, Lars Vogt rounded the circle with a piece from Janacek's Overgrown Path, leaving us to muse pensively upon the perfect combination of science and artistry we had been privileged to share. This was a recital dedicated to the music, without any self-promotion. Composer John Field was once employed to travel and demonstrate Clementi's pianos; were Lars Vogt free to assist ARTEC to demonstrate their acoustic designs, he would be the perfect exemplar of the virtues of their concert halls.

Particular anticipation heralded the appearance of Grigory Sokolov, 1966 Tchaikovsky Competition winner, renowned for his unusual repertoire, including pre-Bach keyboard music on grand piano. His advance programme for Lucerne had two Haydn sonatas and one by Mozart.[left]A portly gentleman, who wasted no time wooing the audience, he sat down and immediately began the small Hob. XVI/23 in F, scaling his playing down to 18 C. dimensions, pedalling immaculately to maintain clarity, respecting notated pauses and observing all repeats with 'through thinking', which never suggested a coming back to the beginning and starting again. Continuity between sections was a hallmark of the evening and it went beyond movements or separate works. Sokolov passed on, without any pause to allow applause, to Hob. XVI/37 in D, whose first movement will have been familiar to many former piano pupils in the audience, and again, after its presto innocentemente finale, he launched straight into the presto of a third Haydn sonata, the E minor Hob. XVI/34, its finale too marked innocentemente, making a smiling finish to the sequence. Sokolov acknowledged the applause with one bow and then retired for the interval, leaving the audience, some of whom had been bewildered to know exactly what they had been hearing, with plenty to discuss.

There was no musical logic in Sokolov's Haydn selection, nor in his way of organising that half of the programme, though it did have a pay-off in that the intrusive epidemic of November coughs (their reach to every seat in the hall a downside of the KKL's 'perfect acoustics’!) was suppressed by the time of the third sonata, perhaps because Sokolov had gradually 'got through' to his listeners, despite Haydn not being everyone's 'cup of tea', as one disappointed critic told me. I could not avoid comparing the reverential atmosphere created for these 50 minutes of uninterrupted piano playing, on a darkened platform in a large concert hall, to the likely atmosphere there might have been when Haydn played this genial domestic music himself, perhaps to a small group of friends more often than at formal concerts?

After the interval, a similar approach to the Mozart C minor sonata of 1784, and the Fantasia in the same key from the following year, paid off. Listed separately in the programme, the ascending flourish which peremptorily concludes the Fantasia led attacca straight into the molto allegro of the sonata, their tempi integrated to make the Fantasia & Sonata an unquestionably convincing major work of a half hour span. There was nothing spurious or eccentric, and I was impressed throughout by the 'rightness' of Sokolov's negotiation of the many tricky transitions, making for an intimate and moving experience in this accommodating large hall. Afterwards Sokolov acknowledged his enthusiastic reception and strode off the platform, remaining backstage for so long that some people left the hall - were they worried about transport, did they lack the day's programme and not realise that a major work from the 19 C was still to come, or did some think that Cesar Franck was not a composer they needed to stay for?

The late addition to the preliminary programme of Franck's Prélude, Choral et Fugue, which rarely features in recital programmes nowadays, was however most welcome, and for me timely because I had the previous week been conducting comparative reviews of versions recorded by Ashley Wass, in1997 the first British winner of the World Piano Competition, (Naxos 8.554484), and by the Swiss pianist Karl-Andreas Kolly (Tudor 7032). My conclusion was that they were fully recommendable and equally so, and that collectors interested in this relatively neglected master (Belgian by birth, French by choice) should acquire both for their unusual couplings, Wass the complete solo piano works, Kolly with his colleagues of the Trio Novanta the engaging piano trios Op 1. These are now quite unknown in UK. They were admired by Liszt, readily bear comparison with Beethoven's regularly programmed Op 1, and deserve re-assessment with a view to their restoration to the chamber music repertoire.

It is hard to compare studio recordings with live performances in large concert halls, but Sokolov took his recital into a new dimension with this complex work, which took my thoughts to Liszt as well as back to the more obvious Bach connection. This was pianism on the grand scale, with no holds barred. The climaxes were thunderous, but counterpointed with utmost delicacy and lucid terracing of the dynamics in the lyrical passages. The arpeggiated sequence with the melody quietly picked out above with the left hand were exquisitely shaped and balanced; at its grandiose return Sokolov showed that he was human with a couple of small smudges, but these were rare indeed in a long recital of uncommon music, played entirely by memory, which demanded tremendous physical and mental stamina. I was left thinking that this work, with its cyclical Lisztian features and free, Beethovenian fugue, should take its turn more often for pianists establishing their virtuoso credentials, as an alternative 'war horse' to the ubiquitous Liszt sonata; the Franck is pianistically harder too, though that may not be evident to the non-pianist listener.

It was unreasonable to expect an encore and as Sokolov did not return to the platform for a long time, people began to depart. Characteristically, though, this was no 'teasing' the audience to milk applause. He returned to he piano, sat down and lightened the mood and, to 'clear the palate' after romantic indulgence, tossed off a delicious Scarlatti sonata, cheekily making it sound later than its period by inverting the balance to emphasise the slow, bouncing accompanying voice. I do not claim to be able to identify each of the 400, but the cross-hands patterns suggested it was not a late one; it is said that Scarlatti trademark was dropped when the composer's girth grew and made them difficult to execute.

By now, one felt that Sokolov, far from tiring, was enjoying the particular pleasure of hearing his own playing, which sounds uncommonly true on the platform (as many pianists before him have testified). Twice more he returned and without prevarication sat down to give us two substantial works, each based on a rondo scheme of a returning statement with a series of contrasting episodes. The first (unidentified) was obviously by Schumann was harsh and demonic, that 'Florestan' persona balanced with 'Eusebius' passages of heart-melting beauty. And finally to a major work by Chopin to bring this distinguished and unforgettable recital to finish almost three hours after starting time. At the time of Sokolov's recital early in the week, it seemed unlikely that press or paying tickets would be forthcoming for us to hear Kissin's sold-out final Chopin recital, which was to conclude the festival, so Sokolov's C# Mazurka Op 59/3 might have had to stand in to represent that key pianists' piano composer; and worthily it did so. A mazurka a major work? With its many episodes and modulations, this extended gem, amongst what is for me the most precious collection in Chopin's oeuvre, certainly merits that thought.

A shared ticket was eventually supplied for Seen&Heard, so I am in a position to report my disappointment with Evgeny Kissin's version of the Chopin 24 Preludes Op 28, but not to comment on how he played the Bb minor Sonata. It was hard to believe that Kissin was playing the same Steinway as had Lars Vogt earlier that day. Billed to be the grand finale of the festival, Kissin's recital was sold out long ahead and he had the hall filled to the rafters, with three extra rows of seating on the platform. Feeling myself to have been 'the only soldier out of step' amongst a sea of adulators (of whom only a few might have turned out on the Sunday morning to hear Vogt) I have to say that Kissin produced the ugliest piano tone in the entire festival. At the end of a week of daily piano playing, pyrotechnic acrobatics characterised by sheer velocity and power fail to impress. Each little piece seemed to be approached to find what Kissin could make of it for himself rather than for the composer, with no ear for the sequential relationships. He pounded the keyboard so that the fast ones thundered by with often idiosyncratic emphases, and the tiny slow pieces, some of which every child used to learn to play (before 'keyboards' and a different repertoire supplanted the classics in school music teaching) were expanded and distorted to the limit of self indulgence. One was left wondering if Kissin had ever interested himself to play instruments of Chopin's own time or to think about how the Preludes might have sounded when new?

We were pleased to have an opportunity to re-appraise Arcadi Volodos,[left] after being disappointed in what must have been an off-day in San Sebastian's summer festival 2000, and were delighted to hear him again in the KKL hall. In Lucerne he displayed his formidable pianistic powers and musical sensibility with absolute conviction, in a wide ranging programme with serious content, before ending the advertised list of items with an 'improved' Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody. He had started with the richly sonorous piano transcription which Brahms himself made of the variations movement of the String Sextet Op.18, followed with Schumann's Kreisleriana, and took us on an interesting itinerary from Schubert to Liszt. The eighteen year old Schubert's first sonata in Eb major, D.157 (incomplete, lacking a finale) was well worth an airing, and Volodos found just the right scale for it. Three Schubert song transcriptions by Liszt were remarkable for their choice and for Volodos' discretion in avoiding any overt display in their elaborate accompaniments; after Der Doppelgänger he imposed the longest unbroken silence before permitting applause that I had ever encountered. After that he relaxed (!) into his own arrangement of the Hungarian Rhapsody No 13, the composer's original being not difficult enough. This formed a perfect bridge to the well judged group of encores, beginning with a tiny late Scriabin miniature and finally an enjoyably outrageous farrago, which I could not identify, of the sort with which Cherkassky used to regale us to end his recitals. For an equally serious and challenging live recital on CD I recommend wholeheartedly Volodos' splendid Carnegie Hall debut with Liszt, Scriabin & Rachmaninoff and, as a surprising centre piece, Schumann's 14 Autumn Leaves Op.99, played with immense delicacy and perfect taste (Sony Classical SK 60893).

Varjon's Bartok & Vogt's Janacek apart, it was the individualist Misha Alperin, [left] opening The Long Night of Improvisation in the adjacent Lucerne Hall, who gave us the most welcome glimpse of some aspects of the potential scope of the instrument. Born in Ukraine, billed as a jazz pianist, but slow to declare himself in that tradition, Alperin began his hour disarmingly with spare and refined little melodies which brought to my mind the contrived and knowing simplicity of Satie, and the children's pieces of Stravinsky, compelling attention to the beauties of the moment and holding our interest to discover what might come next, sometimes bursting into hectic ostinati, and with many a touch of sly, understated humour and oblique musical references. Some of his very personal improvisations in similar vein, recorded in the isolation of his studio on the Oslo Fjord, on the 21st anniversary of his father's death, are collected in Alperin's first solo CD At Home (ECM 1768).

The theme of improvisation, together with the intention to represent all aspects of 'the fascination radiating from black and white keys - - with no holds barred', was represented also in recitals by 'Jazz legend' McKoy Tyner and Bamberg Cathedral organist Markus Willinger. McKoy Tyner (b.1938), John Coltrane's favourite pianist, gave a solo 'piano improvisation' recital of short pieces, a few 'originals' and most worked up from long familiar tunes. His digital facility was unquestionable, but from a jazz outsider's perspective I found his performance old-fashioned and detected little of the essential creative feeling of true, wide-ranging improvisation on the night. He seemed to rely instead upon well worn formulae and patterns, and made no attempt to vie with his classical colleagues in the festival for timbral subtleties. I doubt whether anything uniquely new in his piano playing or treatment of the chosen material was to be heard at Lucerne, despite the publicity build-up. Tyner pedalled generously and brought his own percussion department - a left foot which he stamped loudly and, most disconcertingly, usually just behind the beat! Markus Willinger put the new Goll organ at KKL through its paces, demonstrating the colours at his disposal, but his Improvisation of three choral preludes in different styles and, especially Improvisation of a Symphony in the Romantic style were locked in a dispiriting academicism. For a taste of what contemporary organ improvisation can and should offer, I most strongly urge readers to explore those of the great Parisian organist/composer Jean Guillou, captured on CD. To hear Guillou improvise on the KKL Goll organ would be worth a special journey.

These reflections unavoidably bring to mind regret for the unaccountable exclusion of a representative corpus of really innovative 20 C. piano music from an important festival whose Artistic Director, Michael Haefliger, has been named 'Global Leader for Tomorrow' (WOF Davos) and is praised in a media release for having upheld the Lucerne Festival's commitment to new music. Might Lucerne's KKL (despite box office considerations and probable local conservatism) not be able to risk following the example of Zurich's Tonhalle, where Maurizio Pollini achieved acclamation for a sold-out concert of Boulez and all the late Debussy Études? For a start, I would suggest considering, as a minimum, a shared concert by 'transcendal pianists' of today who specialise in contemporary music. If the idea appealed, Ian Pace of the UK, Heather O'Donnell of the USA and Marianne Schroeder of Switzerland are three of them I know personally and can vouch for. It would not be difficult to programme a sensational and revelatory concert to bring Lucerne's piano festival firmly into the 21st century.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

On the way back to London by Crossair (flying from Zurich shortly a few days after one of its planes had crashed there - and not long after reporting on S&H recent travel experiences, one on the same airline!) the opportunity to attend Mikhail Pletnev's [left] Beethoven sonata recital in the famous, ornate 19th C. Tonhalle was not to be passed by, so soon after his concerto cycle at Royal Festival Hall.

It was salutary to discover that the most expensive stalls seats at Zurich were no match for the cheapest at Lucerne! Before the Pathetique came Beethoven's D minor sonata Op.10/3, with its always astonishing largo e mesto, a highlight of the first half. Moving forwards after the interval, to a small empty block of cheaper seats on the spurned non-keyboard side (where pianos usually sound better), the higher proportion of direct to reflected sound brought a sharper focus. Doing so enhanced pleasure in Pletnev's revealingly affectionate, and at the same time analytic, approach to the Pastorale Op.28; a unique work and not one of the easiest in the canon to interpret. Pletnev finished with a magisterial Op.111, maintained the disarmingly modest demeanour shown in London and, besides the regulation bouquet from the organisers, gracefully accepted an armful of floral tributes from individual members of the audience before obliging with a pellucid Chopin Nocturne for his single encore.

Mikhail Pletnev has demonstrated a devotion to exhaustive exploration of his chosen composers in a fascinating double-CD of smaller Beethoven works, many of them early and almost never played (DG 457 493-2.). Op.111 is a high point of the thrilling record of his Carnegie Hall debut recital in New York (DG 471 157-2). I trust that recordings of the sonatas and concertos will follow soon, and would be especially keen to hear his interpretation of the Diabelli variations, which I would anticipate might encapsulate Pletnev's unique combination of seriousness and playfulness.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Related Recordings

By most serendipitous coincidence, whilst preparing this report for publication, I received two relevant recordings, gifts which I would like to share immediately with S&H readers.

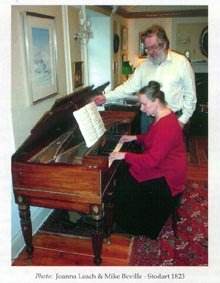

Joanna Leach includes the same three Haydn sonatas given by Sokolov in Lucerne on her latest Athene CD. She plays them stylishly and unfussily on her own characterful Stoddart square piano of 1823. Joanna Leach, also pictured on the CD cover at Haydn's house in Eisenstadt, is a devotee of sensitively restored authentic instruments, with their often different timbres in separate registers, which are sometimes smoothed out and made more 'consistent' in reproductions. Sokolov's discography does not include any Haydn, so interested readers would do well to seek out this very desirable Athene 22 release instead.

In transit via Zurich I had a meeting with the Swiss company Tudor Recording AG. This is an interesting small label which explores 'niche' repertoire overlooked elsewhere. Amongst a number of CDs received was an entirely delightful integrale Tudor 741-752 of the complete Schubert solo piano works, played idiomatically and with evident affection by Gilbert Schuchter (1919-89), [left] who studied with Franz Ledwinka, whom Karajan called his own "beloved teacher, to whom I owe my entire musical education". And, joy of joys, Schuchter is recorded on a sweet-toned Bösendorfer, just right for this music. It includes, of course, that unfinished sonata chosen by Volodos at Lucerne, and if you have a chance to sample, for example, the Grazer Fantasie on the first of the twelve CDs, you will need no more persuading. I suspect that the unknown Schubert piano music has many hidden gems to discover, just as Graham Johnson found whilst recording all the songs for Hyperion.

Peter Grahame Woolf

Return to:

Return to: