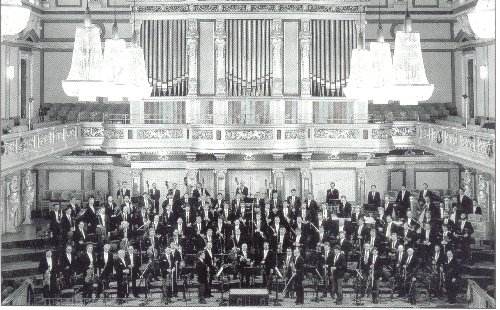

If this concert’s change of programme (with Brahms’ D minor Piano Concerto being replaced by Rossini and Stravinsky) was inspired, then the scheduled symphony, Dvorak’s Seventh, and the Strauss encores, were simply sublime. These were performances that will linger long in the memory and simply confirm that today no orchestra in the world can touch the Vienna Philharmonic.

Seiji Ozawa, a conductor who can occasionally seem bland on record, is riveting in live performance. He is the very antithesis of Karajan – and almost a clone of Bernstein, and yet somehow he inhabits both of their worlds with consummate ease. His podium manner – jiving in the Rossini and Stravinsky, febrile in the Dvorak – encourages this orchestra to explore sound and colour as they do under few other conductors. His batonless conducting coaxes from them (as Karajan did before him) a sound world which seems utterly timeless in its beauty.

Rossini’s Barber of Seville overture was given in a scaled down performance, but one which managed to achieve quite exceptional heights of expressivity. One of many examples was the super-refined playing of the violins who achieved exquisite beauty of tone in the higher harmonic line. The bow-on-string playing was quite stunning, the projection of pianissimos on the E string in particular being as clear as glass. Add to this tellingly phrased woodwind playing and Ozawa drew us into a performance which gave us the drama of the instrumentation with an urgency of delivery.

Stravinsky’s Jeu de cartes was again beautifully coloured, almost kaleidoscopic, the three card deals each being rhythmically different from the preceding one. Perhaps Ozawa was not razor sharp enough in some of his phrasing, the bite which this music ideally needs somewhat blunted by over-refined string tone. Yet, brass were rigorous and woodwind as fleet as horses, each section providing counterpoint playing of character and brilliance. There was no shortage of violence in the work’s closing Final Dance – although this was playing on the most expensive set of cards available.

Dvorak’s Seventh is one of the great nineteenth century symphonies and this was a great performance of it. It can be a problematical work to bring off, both on disc and in live performance: it is overwhelmingly tragic in mood, but also needs extraordinary care taken with orchestral balance. That Ozawa gave us an interpretation that was broadly sombre in phrasing, but also blazing and wild during the climaxes, and with every phrase so tellingly played, was a tribute to his conducting. This was a performance in which all the contrasting emotions and themes were bound together as cogently and definitively as they could be. There were many wonderful moments: the darkly imbued pathos of the maestoso’s close, the clarinet’s heartfelt melodic opening of the second movement and the oboe’s recapitulation of this theme, as inward and impassioned as I have ever heard it, the growling basses during the Scherzo’s Trio and the astonishing phrasing during the stark, tragic opening of the chorale like march that opens the allegro. Ozawa imbued that final movement with rare clarity and a flexibility to rubato which gave it a synergy, an arc-like expressivity of Brucknerian nobility. Never once did this movement lack the pace it sometimes can, and when the coda arrived it did so with genuinely tragic power. The playing was fabulous throughout – the orchestra responding to every one of Ozawa’s on podium movements with a rare and organic understanding. The strings were sumptuous, the brass tore at the walls with Babylonian power and the woodwind were felicitous and feverish in their phrasing.

To crown an evening of quite magical playing the Vienna Philharmonic played two Strauss encores. Seiji Ozawa is to conduct his first New Year’s Day Concert with this orchestra on 1st January 2002 – this brief preview suggests it should be a quite special concert.

Marc Bridle

The next Classic International performance is on 9th December when the Royal Concertgebouw play Mahler’s Sixth Symphony under Bernard Haitink. The Vienna Philharmonic return to London on 11th April under Lorin Maazel for a concert of Bach, Mozart and Mendelssohn. Details and bookings can be made at www.rfh.org.uk. The Vienna Philharmonic’s website is at www.wienerphilharmoniker.at.

Return to:

Return to: