The Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich was rebuilt, with opulent decorations in the old style, after the devastations of the Second World War. Five narrow tiers cling to the high horse-shoe shaped walls. The wide auditorium is well raked to provide good sight lines and the acoustics, experienced from three different positions, were excellent, the sounds from the orchestra pit and from the stage emerging crystal clear.

We saw three very different repertory productions in one week and gained a good idea of the very high standards set and maintained by the Bayerische Staatsoper. The informative program books contained libretti and essays, as well as synopses in English and French.

Elektra by Richard Strauss

Rarely have we been held so spellbound. We listened and watched, on the edge of our seats, totally hooked by Herbert Wernicke's staging of Elektra, for some two hours without interval. This tragedy of guilt and revenge unfolded itself against visually powerful, apt yet uncomplicated sets, a perfect foil and counterpoint to the painful, tangled and complex emotional webs uniting the characters. Against an aura of stillness created by the sets and brilliant lighting effects the music could assume life under the expert musical direction of Peter Schneider, the deceptively simple but highly sophisticated settings helping to focus attention on every note, every movement of the singers. This utterly modern looking, and sounding, music drama was presented with meaningful and thoughtful artistry and a very high standard of singing all round.This production achieved a unity of high intensity between the musical and the visual aspects of the drama. It released the emotions and the psychological depths inherent in the story of Elektra, seizing our attention and ensuring our involvement from the very first moments. A gigantic black wall, nearly full stage height and width, just slightly tilted, closed off most of the stage and brought the action up-front close to the audience. From underneath this oppressive wall the chorus of women just managed to crawl out. Elektra sang sprawled and facing us on a forward tilting platform and the women conveyed a picture of abject exclusion and doom, singing crouched on all fours.

An enormous, heavy red cloak makes its round, like an emblem of the fearful inheritance of guilt assumed and revenge taken up and passed on. A grotesque and grimacing Klytämnestra, in a tortured performance by Jane Henschel, appears at first trailing this cumbersome and weighty object behind her, every now and then kicking it out of the way with brusque, animal like stabbing movements, as if to rid herselfof something unpleasant. She divests herself of this cloak and throws it over her daughter Elektra, who wraps herself in it, as if to enfold herself with the need for revenge which she totally accepts and assumes that the Gods have assigned to her. She, in turn, passes this fateful legacy on to Orestes, her brother (sung by Monte Pederson with great conviction) who proudly assumes the mantle of responsibility to fulfil destiny. Particularly noteworthy was Gabriele Schnaut in the fearfully demanding and commanding part as Strauss's eponymous heroine, Elektra.Elektra will be included in the important 125 Jahre Munchner Opera Festival 27.6. - 31.7. 2000, with Deborah Polaski as Elektra and Marjana Lipvosek as Klytämnestra.

Aida by Verdi

We have some reservations about David Pountney's staging of Aida. We did not expect to be taken on a history tour of the Middle East, nor did we deplore the lack of palm trees or sphinxes for orientation. Although Verdi set the action in Egypt, and the opera was first performed on the occasion of the opening of the Suez Canal, Aida was, in true Orientalist fashion current at the time, about the West, albeit talked about at a distance.However, we were disconcerted to be landed in the middle of a shambles of a building site, difficult to negotiate and to find your way through and out of! Deconstruction gone so far as to make reconstruction problematic. There is a point to the exercise of defamiliarising the over familiar, in order to tease out meanings, but there is also a danger of throwing out the baby with the Nile water and of interrupting or even counteracting the flow of the narrative and the music to such an extent as to lead to a divorce.

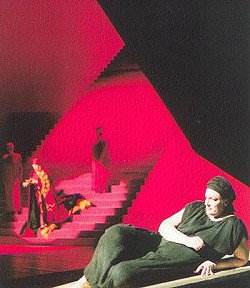

Thus we had a band of bound, mummified but living slaves constantly shunting a huge wall around. It is composed of two skins, broader and split at the base to create a narrow triangular opening, for humans to emerge like beetles out of a crevasse. Tall metal poles are tied into a wigwam structure, a boy scouts pyramid perhaps? Amneris and Aida meet among vertical, suspended planks, held together with spear-like poles, perhaps an allusion to the war which has thrown them together? Another free-standing wall, every now and then also taken for a walk around the stage, has a first floor balcony attached to it which serves as a platform for the trumpeters in the victory parade. A separate, recessed rubbish dump turns out to be a sacrificial altar, where one of the prisoners is bundled off, only to reappear later paraded as an offering of dismembered legs and arms - war is a nasty business!

Radames makes his appearance standing in a chariot which looks like a polished, oversized cooking pot with handlebars, only to sink below stage and to disappear, while a large rock descends from on high to sink into the ground in front of him; an allusion to hollow victory and doom to follow? A miserable, spindly specimen of a tree, suspended sideways, rights itself and rises heavenwards into the beyond, almost imperceptibly slowly, expressing perhaps that all hope is vanishing for the protagonists. For some of the audience sitting close by, all hope had long gone of making any real sense of the stage picture, the day being saved only by some wonderfully expressive and integrative dancing which conveyed profound characterisations of the personalities of Aida, Amneris and Radames and their conflicts and painful relationships, and by the musical performance under the direction of Jun Mark. The singing was again of a very high standard, with Sylvie Valayre an affecting Aida, Nina Terentieva a sonorous Amneris, Dennis O'Neill (often enjoyed at WNO) a sweet-toned Radames, the only notable failing being Alexander Agache, whose relentless forte singing as Aida's father Amonasro spoilt the balance in the Nile Scene trio.

With the third opera we landed on safer and firmer territory:

Der Freischutz by Carl Maria von Weber

There was no problem integrating the visual and musical aspects of this production. Thomas Langhoff's staging exuded charm, humour and affection towards a work which is deeply embedded in, and draws upon, a vernacular culture. The stage picture was pure joy to behold in all its many details. The fairytale landscape of cut-out woods surrounding a fairy tale house, the proscenium arch decorated with hunters' trophies, and the costumes were all thought through with loving care. The stage lighting from bright daylight to dusk, to dark and to the nightmare fantasy scenes added a magical quality to the work. The serious aspects of this opera were perhaps somewhat submerged.The emotional mayhem and the hobgoblins and nightmare conjured up were not quite scary enough, though in the Wolfsschlucht scene the bawdy eroticism was given free reign in the Devil's den, pointing to the problem of sexual prowess, or the lack of it, the fear of not being able to 'shoot' properly to gain a woman, which is one aspect underlying Freischutz.

It is perhaps also difficult to represent the revolutionary nature and status of this opera, which was first staged in 1821. Over time Freischutz has mellowed and become a much loved, and unquestioned, people's opera, and the revolutionary stances and democratic ideals it contains are just so much history. In 1821 it was daring to put ordinary folk centre stage who could talk and sing about their concerns, their loves and fears. Der Freischutz still retains our affection for this quality.

The veteran conductor Leopold Hager conducted with unerring pace and concentration an opera which is in the Munich opera orchestra's blood, and the excellent cast included Petra Maria Schnitzer, Jan-Hendrik Rootering, Alfred Kuhn, Peter Seiffert and Pavlo Hunka, supported by a large, lusty chorus of villagers.

Bayerische Staatsoper under Sir Peter Jonas, its Staatsintendant, is clearly in excellent health and readers are encouraged to explore the Munich opera festival on www.bayerische.staatsoper.de

Alexa Woolf

Return to:

Return to: