One's experience of Prokofiev's socialist realist opera Semyon Kotko

had, until this gloriously sung stage production, first seen at the Mariinsky

Theatre in St Petersburg in June last year, been limited to an ancient Melodiya

LP of extracts, and the suite of eight highly characteristic orchestral

movements, recorded a decade ago by Neeme Järvi on Chandos

[CHAN 8803]

order from

Amazon With its occasional overtones

of Romeo & Juliet, gorgeous orchestration and bittersweet lyricism,

it is surprising that the suite, at least, has not become better known.

The opera is set in the Ukraine at the end of the First World War. The German invasion, and the civil war following the revolution, was real living history for all Russians, though one suspects that in 1939 many of them may have been shielded from the horrors of the ensuing famine in this most fertile of lands. The music tells us that for Prokofiev the setting was passionately felt, the idyllic country of his childhood now become nightmare in the aftermath of invasion, pillage and civil war, though what his real views were on the events depicted only the satirical staging of the red army at the end give any hint.

It was composed and produced very quickly, the first two acts being completed in seventeen days in July 1939 and it was produced in 1940. The opera was to have been produced by the celebrated Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold, but he was arrested at about the time Prokofiev completed the piano score and was never heard of again. Although Soviet commentators emphasised the heroic, folkloric and lyric aspects of the score, it only briefly found favour and was not heard again in the composer's lifetime, its existence scarcely realised by most lovers of his music.

The opera proved to be on a much bigger scale than one had expected, five acts, presented at Covent Garden with intervals after Acts II and III, and a total running time of two and a half hours. The story, set in 1918, concerns Semyon Kotko, a demobilised soldier returning to his village. With opportunities for many vignettes, village comedy, love-matches, horror, tragedy and orchestral tone painting, this is a Mussorgsky-like historical fresco. There must be over forty notional changes of scene within the five acts, and the true subject is, like Boris and Khovanshchina, the poor suffering people; and it would lead on, three years later, to that even larger-scale musical fresco War and Peace.

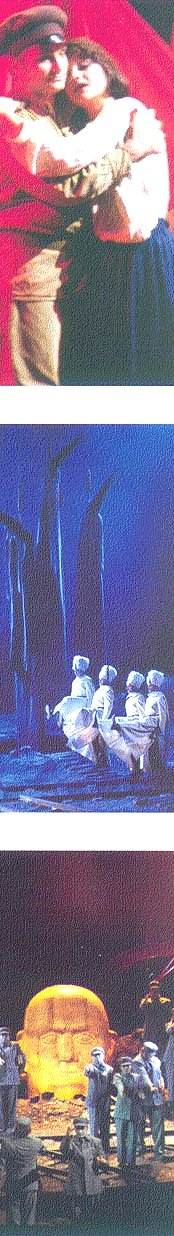

The local estate has been divided up between the villagers, and Kotko is due to receive his small portion. His girlfriend, Sofya (Tatiana Pavlovskaya) and his mother (Ludmila Filatova) were both warmly drawn. Sofya's father, Tkachenko (an ungrateful role nicely characterised by Fyodor Kuznetsov), thinks him unworthy of his daughter, and schemes to marry her to the former landowner Klembovsky, convinced that the old days will return. His aspiration is reinforced by the arrival of German soldiers and the anti-Bolshevist Haydamaks, who surround the village. Tkachenko collaborates, naming the leading Bolshevik villagers, who are hanged, and the village burns.

Kotko and Mikola (the sweetheart of Kotko's sister, Frosya) escape to partisans on the steppe. Frosya arrives from the village to tell of reprisals and atrocities and that Sofya is being forced to marry Klembovsky. Attempting to rescue Sofya, Kotko and Mikola are captured. Their imminent execution is gloated over by Tkachenko who taunts Semyon. But the Germans withdraw and the tables are turned as (Seventh Cavalry-like) the Red Army arrives and, all too-earthbound, all hymn the struggle for the freedom of the people.

There were no vocal weakness in a strong company, and on its last performance in London Yevgeny Strashko sounded and looked the name part, though one has to say that one did not warm to Kotko as a real hero, rather than a manufactured one. More realistic was his friend Mikola sung in this performance by Vladimir Felenchak, and Zlata Bulycheva as Frosya.

The 8 July performance broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 whetted ones appetite to see it in the theatre. I have not yet heard the CDs by the same company under Valery Gergiev with Viktor Lutsiuk in the title role, but on this evidence they will be indispensable. [Philips 464 605-2] [see review] This is an opera which one really needs to see in space to sort out what is going on; perhaps it would work best on film?

I did not warm to the Covent Garden set. Most of the Kirov Season had been presented with traditional scenery and staging, Tchaikovsky's Mazeppa in particular receiving rave reviews, and effectively reinstating it for London opera lovers after the excesses of a misplaced 'dirty mac' production at the ENO some years ago.

But for Semyon Kotko, with its constant scene changes, the set designer Semyon Pastukh has gone for an all purpose landscape of twisted railway lines, an upturned locomotive, and vague hints of wartime and industrial detritus, and with a large central hole through which the new Covent Garden stage machinery raises and lowers a platform as required, ending with a (presumably satirically intended) statue of Lenin. Characters emerge from holes in the ground variously lit from within, and while it provides a ready solution to Prokofiev's apparent intention for cinema-like dissolves, there is none of the atmosphere of a village in the Ukraine, and I am afraid it is very reminiscent of our more 'progressive' opera producers in their more self-indulgent vein.

This is probably not an opera one wants to hear complete very often, but it is full of cherishable moments that one may frequently like to revisit. Not one of these is the end, where at its most blatantly Socialist Realist the Red Army sing in all too four-square 'patriotic' mode. The production has the chorus all now dressed in pale grey Mao tunics and (to be sure we all got the allusion) waving little red books. This was comic in a way that what had gone before did not deserve. Was this Prokofiev himself protesting at having to write such stuff, amid the repression signalled by Mayerhold's disappearance? It is difficult to imagine it being done straight.

Overall a tremendous and memorable occasion, very warmly received by an almost capacity audience. What a wonderful company, reminding us what Russian opera is all about; the importance of continuity and tradition, and how a large company of gifted singers (many of the company changed on different nights) and a really powerful chorus can transform such a score. The orchestra, too, was gripping under the sustained intensity of Valery Gergiev's musical direction.

Even if you were not able to go, the large-format, very glossy 156-page coloured programme of the whole Kirov season was superb value with its price halved to a fiver towards the end of the Season, and it is worth seeking out.

Lewis Foreman

and Peter Grahame Woolf adds:-

'- - - I was fortunate to be able to see the Kirov's Semyon Kotko, and War & Peace too, with standby & return tickets. I preferred the non-realistic Kotko production to the more conventional one of War & Peace, and indeed the lesser-known opera Semyon Kotko as a whole also.

There is no denying that the last act is a dreadful let-down, but there is a long tradition of jingoistic opera, even in England (see my S&H review of Purcell's King Arthur!). But Act 3 is a towering masterpiece in Prokofiev's whole oeuvre.

The Kirov CDs are

magnificent, and the passage leading up to Lyubka's lament for her sailor

betrothed (Ekterina Solovieva,Track 10) to the end of the Act is overwhelming

- once heard, you will never forget the endlessly repeated cry of anguish,

which is eventually taken up by the whole chorus. (PGW, Editor

Seen&Heard)

Return to:

Return to: