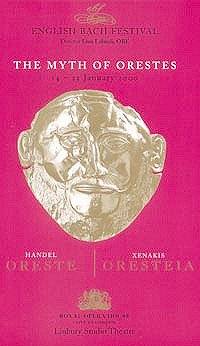

This was a first presentation of opera at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden's new studio theatre, deep underground beneath the new development. Lina Lalandi has pursued two strands of her personal enthusiasms since founding the English Bach Festival Trust in 1962. A harpsichordist herself, she has sought authenticity in presentation of baroque music and opera. She has also championed 20th Century Greek music, and was importantly responsible for bringing Skalkottas, so long neglected, to British notice.This season has brought together two versions of the classical stories about Orestes, Handel's opera Oreste after Euripedes' Ihpigeneia in Tauris and Xenakis's Oresteia, which draws on Aeschylus. Both were presented in a basic staging dominated by simple Corinthian columns and pilasters, moved around in the Handel opera to indicate changes of location.

Opera Seria demands suspension of disbelief on many levels. Most often, Handel operas are given from a modern perspective for today's audiences, sometimes sending up the period conventions to extract maximum humour, or with a multi-layered historical awareness linked to spectacular staging, ENO's Alcina at the Coliseum (see S&H review, November 1999) being a recent prime example.

Lina Lalandi takes the opposite route, bravely seeking to present Oreste in an 18th Century style, with recreation of dances as they might have been seen in the 1730s. This opera has not been given in Britain since its few original performances at Covent Garden in 1734. Handel was busy then with two wholly new operas for the same season, Ariodante and Alcina, two of his finest as they turned out. Oreste had been hurriedly cobbled from existing music, mixed and adapted to a new libretto with his opportunistic skill and professionalism. The transpositions work well, and there were many moving arias and a superb duet for Oreste (Louise Winter) and his wife Ermione (Lynda Russell) anticipating death. The story line throughout was one of repeated impending sacrificial slaughter, under the instructions of a tyrannical and insecure King (John Rath, bass), violent death always round the corner but narrowly averted at the last moment. Swords were brandished, but never struck home, people were chained and released, guards and servants obeyed conflicting instructions, stood motionless during arias, and propelled the tall, light-weight marble columns around easily as required, dispelling any semblance of illusion. Finally, the despot is overthrown and killed (offstage), concluding with a sequence of dances to celebrate the happy turn of events. One gradually accepted the formality and naivety of the conventions.

There were minuses and pluses. With staging so rudimentary, no doubt because of financial constraints, it might have been better to eliminate the scenery altogether? However, there was an unavoidable, topical thought that pushing around Corinthian columns by hand entailed no risks of cancellations of performances for 'technical reasons', which had blighted the re-opening of the Royal Opera House itself!

The austere modern Linsbury Studio, fine for Xenakis, was not really a suitable venue for Handel. The seating is cramped (significant in a three-hour opera with only one interval) and the front row was virtually inside the orchestra pit. The folding seats provide a surprise - when someone sits down in front of you, you are liable to receive a smart tap on your knees! The direction of the orchestra (conductors from the harpsichord Howard Williams/Laurence Cummings - no indication which of them!) was lively, and there were some nice contributions from baroque oboes and bassoon, but the acoustic is very dry at the Linbury Studio and showed up limitations of the string playing - with vibrato eschewed, tuning becomes critical. The acting was basic, as was usual in opera right into the early twentieth century, with nothing to distract from the lengthy arias themselves. Oreste was given in Italian, with no surtitles (Gawain, in English, was surtitled!) so the recitatives inevitably became tedious.

On the other hand, the singing was of a high standard in the performance I saw, and the dancing was pleasing, even if not always conventionally elegant. Jennifer Smith was imposing as the Priestess Ifigenia grappling with her divided loyalties, Joseph Cornwell (tenor) effective as Oreste's friend, Victoria Simmonds winning, if vocally a little underpowered, as Ifigenia's frustrated suitor, who surprisingly becomes the head of the rebels who overthrow the wicked King at the end! No counter-tenors for any of the chief male protagonists. Louise Winter has a lovely, individual voice and excelled as Oreste, whether heroic or tender, Lynda Russell partnered her/him well as Ermione, and John Rath was suitably intimidating as the tyrant Toante (King Thoas of Tauris).

A worthwhile revival, two and a half centuries overdue!

Peter Grahame Woolf

Return to:

Return to: