This final homecoming of Martinu's original version of The Greek Passion is a resounding success, taken on its own terms and laying aside the weight of operatic tradition. Martinu had condensed and adapted the novel Christ Recrucified by Nikos Kazantzakis to construct the English libretto for this unconventional and not easily classified work, intended for Covent Garden in the 1950s and championed then by its music director, Rafael Kubelik. In 1957 it was however rejected by the Covent Garden Board for what now seem rather flimsy reasons. Criticisms led to a drastic reworking during the last two years of Bohuslav Martinu's life. The through-composed second version was only premiered in Zurich after his death in 1959. The time is now ripe and right for Martinu's original conception.Its technique has much in common with cinema, with short scenes and abrupt changes of mood and method. There are no ordinary operatic arias. The protagonists speak and sing in arioso, with accompaniment varying from a single instrument to full orchestra. There is even a speaking narrator, outside the action - a common device in theatre and cinema, but exceptional in opera. Quick recitative based on speech rhythms, with brief orchestral interjections, was removed for the Zurich version of 1961. The religious dignitaries use quasi-ecclesiastical intonation, and the chosen apostles oscillate between the two as they struggle with their new roles.

The religious theme reflects Martinu's own return to faith, as Anthony Burton explains in his attempt to evaluate Martinu's controversial standing during his lifetime and since his death. The lavish programme book explores many of the issues raised and is a valuable source for the future.

Martinu's instantly recognisable and unique compositional voice is present in short passages of characteristic orchestration, with leitmotifs but no elaboration of large musical structures, because he is at pains to make the text audible and intelligible at all times. However, the orchestra provides far more than mere background music, and Ales Brezina prefers it to be thought of as a true music drama and classified as an opera.

The original manuscript has become widely dispersed but none of it was actually lost. We are indebted to Ales Brezina for reassembling and reconstructing it over a period of two years and for his tenacity in helping to bring this work as first conceived into circulation. One hopes that this production will remain in Covent Garden's repertoire to give many more people a chance to participate in this enthralling drama.

This production [Photo, The Times], first seen in Bregenz last year, is directed with thoughtful artistry by David Pountney. With the help of a stunningly effective set by Stefanos Lazaridis a textual unity, in tune with post-modern sensibilities, is created out of a myriad of episodic, fast moving musical, verbal and visual elements.It is no mean achievement to get across to a secularised audience moral arguments dressed in religious terms. Broad themes borrowed from Christian mythology are interwoven with historical and political elements. We are confronted with an established, but amoral, hierarchy that shores up its authority with pomp. It is represented by the priest Grigoris, who makes his first appearance with his entourage dressed in red and gold vestments. In stark contrast the people are all dressed in black, except for the village elder, dressed in white and also part of the establishment, who needs to stand up and out against the common folk. The refugees who are led by their priest Folis represent the counterpart to this established order. They are dispossessed but moral authority is vested in them. Caught between these two conflicting poles are the villagers. For some of them, especially Manolios, the Christ in the village Passion Play and Katerina as their Mary Magdalene, this conflict becomes intensely personal. For all of them chosen the responsibility towards, and understanding of, the Gospels become more than a play for acting in. They are led to enact 'The Word'.

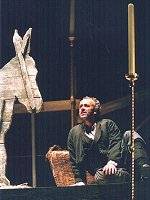

[pict, credit Bill Cooper] Conceived as a mass opera, with choruses of villagers and refugees the main protagonists, the large cast worked well together and every small part was well taken. Even the main characters have relatively small parts; those who must be mentioned include the two opposing priests, Esa Ruuttunen and Gwynne Howell, Jorma Silvasti as the shepherd/Christ, Marie McLaughlin as Katerina/Mary Magdalene, Robin Leggate reluctantly assuming the destructive role of Judas Escariot, and Timothy Robinson as the pedlar Yannakos/St. Peter (Illustrated with his Ass) who repents, confesses and is forgiven evil intent. Charles Mackerras inspired the orchestra with conviction in bringing this brave venture to such gratifying success, another notable service to Czech music by its most famous champion.The internal, individual struggles, the external conflicts, the different and differing perspectives, and the interweaving of complex but accessible themes are pulled together by a sensational revolving set by Stefanos Lazaridis. This unified and unifying open structure of great height makes the events weaving all the way up and through it transparently accessible. The way leads from a cave-like underneath, up a steep hillside through small platforms which double up as interior spaces. The inside and the outside are combined and can be seen to give metaphorical expression to the way the personal becomes subject to the social and vice versa. The large bells at the apex of the set are not only made to ring, but seem to resonate more widely with Martinu's early life, spent in a bell-tower. Interspersing oil lamps with the bells further accentuates the weaving together of the personal interior with the social exterior elements of this drama.

As a crossover art, opera has an outstanding ability to tap emotions and provoke thought. It can turn the specific into the universal and, almost at a stroke, make it into a topical and relevant issue. Thus, the insider/outsider conflict, which underlies The Greek Passion, is brought home to us very forcefully at the end of this production (in case we had so far failed to see the light!). The Greek refugees infiltrate the stalls from the stage as the music drama finishes, and we are confronted by the issues raised by today's refugees in our midst.

costume designs by Marie-Jeanne Lecca

Peter & Alexa Woolf

Charles Mackerras' 1991 recording of The Greek Passion (revised version) is available on Supraphon 10 3611-2.

Return to:

Return to: