Robin Milford - The middle period songs (1930s)

by Peter Hunter

Whereas the main interest in the songs of the 1920s is the development of the initial material of each song, the main point of interest in the 1930s songs, apart from developmental issues, is the more individual style of these compositions. The songs of this period display three main areas of musical style. First, a style influenced by the English ayre (brought to prominence in the early twentieth century by Peter Warlock) through melismatic decoration and chordal figuration. Second, a language using features derived from English folk-song such as modality, repeating melodic units and phrases and lighter textures. Third, a more progressive style involving tonal/modal ambiguity, juxtaposed sections of differing character, greater use of chromaticism, more angular melody with wider ranges, greater use of dissonance, increased harmonic experimentation, constantly changing time patterns (albeit through attention to poetic metre) and wider dynamic and tempo ranges.

The 1930s songs form Milford’s main output of published solo song. Details are shown below.

| Song |

Composition Date |

Publication

Date |

Publisher |

| ‘Daybreak’ |

1930 |

1931 |

OUP |

| ‘So sweet love seemed’

( No. 1 in Four Songs with Piano Accompaniment ) |

1933 |

1933 |

Novello |

| ‘Elegy’

( No. 2 in Four Songs with Piano Accompaniment ) |

1933 |

1933 |

Novello |

| ‘Love on my heart’

( No. 4 in Four Songs with Piano Accompaniment ) |

1933 |

1933 |

Novello |

| ‘Cradle Song’ |

1935 |

1936 |

OUP |

| ‘To Sincerity

( No. 1 in Four Hardy Songs) |

1938 |

1939 |

OUP |

| ‘The Colour’

( No. 2 in Four Hardy Songs) |

1938 |

1939 |

OUP |

| ‘If it’s ever spring again’ *

( No. 3 in Four Hardy Songs) |

1938 |

1939 |

OUP |

| ‘Tolerance’

( No. 4 in Four Hardy Songs) |

1938 |

1938 |

OUP |

| ‘The Pink Frock’ * |

1938 |

1939 |

OUP |

| ‘I will not let thee go’ |

1939 |

1940 |

OUP |

* = not discussed below but given reference in the chapter conclusion

The songs of this period show the extremes of Milford’s emotional temperament. The years from 1930 to 1939 were a period of relative emotional calm, tranquillity and security for Milford. He was happily married to Kirstie, and Barnaby, his son, was born in 1935.

Following ‘Daybreak’, songs reflecting the continued happiness of married life are ‘So Sweet Love Seemed’, ‘Love on my Heart’ and ‘Cradle Song’. ‘The Colour’, ‘If It’s Ever Spring Again’ and ‘The Pink Frock’demonstrate the composer’s good spirits at this period. ‘Elegy’, however, shows Milford in a pensive mood and, probably, reveals the insecure part of his nature which cannot quite accept that good things will last. By 1938, however, the storm clouds were rapidly gathering over Europe. Milford was very much aware of the seriousness of the situation and the various repercussions of possible events in Europe wrecking the security of his calm existence, not to mention the uncertainty that possible war would bring to his life. ‘To Sincerity’ and ‘Tolerance’ are darker songs, showing Milford’s wide range of mood and style, including pensiveness. The songs from 1939 onwards display a shift in musical language to a more developed form of style with more angular melodies, greater chromaticism, thicker textures, wider tonality and dissonance- features which Finzi felt did not represent Milford at his best. ‘I will not let thee go’is the only published song to demonstrate this shift as Milford made no effort to have published any of his songs written after 1940 - nor, indeed, did he discuss these works with Finzi.

Milford’s main 1930s published songs are contemporaries of the Finzi songs written before 1939 (Finzi collected his songs into sets for publication, dating from the 1920s). The songs of this period fall into particular categories: ayre-influenced, cradle song, folk-influenced, and dramatic. Three songs fall under the first category, ‘Daybreak’, ‘So sweet love seemed’ and ‘Love on my heart’. With reference to the influence of the Elizabethan ayre on twentieth-century English song, Hold highlights the fact that Vaughan Williams’ first song of importance, ‘How can the tree but wither’ (published in 1934 but written at the end of the previous century) was ‘a deliberate attempt to recreate the Elizabethan Ayre’ [1]. This ideal (also used by Warlock and Finzi) was taken up by Milford when he employed characteristics of the Elizabethan ayre (such as repeated chords and delicate textural figuration) in a number of songs (e.g. ‘Daybreak’).

‘Daybreak’ serves as a ‘bridge’ between the early and middle period songs through its similarities with the songs of the 1920s and its melodic, harmonic and textural developments. With the epigraph “For My Wife”, ‘Daybreak’, a through-composed song, serves as a link between Milford’s 1920s style and that of the 1930s. The words are attributed to John Donne (1572-1631). This poem is not, however, now thought to be by John Donne. Milford came across it, presumably, in The Oxford Book of English Verse, edited by Arthur Quiller-Couch and published in 1900. In the first half of the twentieth century, this was the authoritative collection of English poetry. The title, ‘Daybreak’, was, probably, invented by Quiller-Couch himself.

The poem itself was first published in 1612, under the title Break of Daye, with the signature ‘J. D.’, in John Dowland’s Pilgrim’s Solace. It might, therefore, be John Dowland’s own work. It was printed again in Orlando Gibbons’ XVI Madrigals and Mottets in 1614. However, in the 1665 edition of Donne’s poems, it was claimed as the first stanza or section of a longer poem whose next three verses (beginning ‘ ‘Tis true, ‘tis day; what though it be?’) are indisputably by John Donne.

Traditionally, the lines in question were accepted as by Donne until after the Second World War, when scholarly research suggested, to the satisfaction of most, that the poem was bogus Donne, partly because the metre does not fit with the genuine Donne stanzas. The view now is that the 1665 editor of Donne either misinterpreted the ‘J. D.’ signature or deliberately carried his enthusiasm for inclusion too far. The fact that the lyrical style of the lines seems to be almost begging for a musical setting (while John Donne’s poetry frequently has a forthright spoken quality to it) points to Dowland as the writer of the words. In ‘Daybreak’ the poet implores his lover to remain with him. The song commences with emphasis through a repeated crotchet figure, forming a one-bar introduction. This figure becomes central to the entire accompaniment, suggesting both constancy and the beat of time.

From the calmness of the first phrases (bars 2-9), ‘Daybreak’ starts its development at the phrase “The day breaks not” in bar 10. The poet explains that it is not the day which is breaking but his heart. The composer gives an unusual accent to “The”, on this occasion through use of high melodic register and a flattened mediant chord. He emphasises the negative aspect of the first half of the phrase “The day breaks not” through a falling melodic contour and a bass falling gesture using the dotted crotchet-quaver unit - modulating to F major through a Vd7 - Ib progression. The more positive statement suggested by “it is my heart”, however, is illuminated by use of a melodic ‘mirror’ where the contour now rises - further illuminated by a modulation to Bb, again, through the progression Vd7 - Ib.

The following phrase (bars 12-16) forms the poetic core where the poet suggests parting. It is painted by rising conjunct quaver figuration in the piano right-hand (bar 13); imitation in the accompaniment between the lower right hand in bar 13 and the bass in bar 14; a sharpened 5th of the tonic (Bb) triad in bar 14; syncopated melodic decoration of “I” in bar 15 through subdominant and supertonic harmony; and a definite emphasis on “must part” through V-I closure.

The poet now becomes more emphatic. Milford emphasises the words “Stay! Stay!” by melodic and harmonic declamation on a tonic Bb chord with a flattened seventh in bar 17 and, surprisingly, a C chord in bar 18. Use of longer durational melodic notes and harmony (dotted minims) are dramatic at this point, especially with the repeated crotchets in the middle texture possibly, possibly, suggesting the poet’s pounding heart. The first “Stay” (‘fortissimo’) suggests a strong command while the second “Stay” (melodic ‘forte’ against a ‘mezzo-forte’ accompaniment reducing through a ‘decrescendo’) perhaps implies the poet’s growing acceptance of the inevitability of parting.

The effects of departure are foretold. The broken rhythmic figuration, characterised by rests preceding the melodic phrase on “or else my joys” (first heard in bars 11 and 12) suggests hesitation on the lover’s part and throws the accented “else” on the third beat of the bar. The effect is particularly successful amidst continuous crotchet figuration. This melodic phrase is derived from a repeating crotchet Vd7 chord in Bb, resolving on a first inversion tonic chord on “joys”. The word “die” is, appropriately, painted by an F minor chord with an added 6th, i.e. minor tonality with dissonance.

The overall commanding impression of this phrase is further painted by the use of the prominent nature of one harmony per bar. Milford adds to this image through use of a dotted minim note in the melody and the upper right hand of the accompaniment during the first part of the phrase.

The final phrase (bars 21-25) is the dramatic climax of both the poem and song. Milford responds with repeating supertonic harmony with added 7th and 9th which is responsible for melismatic decoration of one of the most climatic words in the poem - “perish” in bars 21 and 22 - employing conjunct semiquaver figuration. Repeating first inversion tonic chords permit a rising triadic conclusion to the word “perish” in bar 23 and superimposed 3rds on subdominant harmony decorate the words “in their” in bar 24. Such harmony in bar 24, of course, creates a musical accent and stress on these unaccented words. The phrase moves beautifully to its final poetic accent through IC, V.

At the conclusion of the voice line “[And perish] in their infancy” Milford introduces one of his typical subtle surprises - use of an altered IC- V7-I progression on “infancy” (bars 24-25), where the tonic chord contains a flattened 7th. The coda (bars 25-end) helps to retain the interest generated by the image of perishing in bar 22 through the accompaniment not only imitating the melismatic voice-line of bar 22 but by employing imitation between the registers - right up to the perfect cadence. This also highlights Milford’s ability in employing a fragment of material in an inventive and interesting manner to the ear.

Modulations are an important aspect in the interaction between text and music of ‘Daybreak’. Swift modulations between the subdominant, dominant and tonic highlight particular words - examples include F major for “O sweet” (bars 2-3), “eyes” (bar 9) and “not” in bar 11; Eb major for “light” in bar 6; Bb major for “rise” in bar 5; “heart” in bar 12, “part” in bar 16 and “joys” in bar 20. Chromatic shifts give emphasis to specific phrases - examples include the shift from the F tonic chord to the flattened submediant chord for “The day breaks not” in bars 10-11 and the shift from Bb chords to F minor chords in bars 20-21 for “joys will die”.

Although ‘So sweet love seemed’ is in strophic form, Milford creates an accompaniment of quite diverse character for verses one/two, three and four, thus ensuring constant interest to match that of the poet. This song is also, like Daybreak, set in Bb major.

Milford hints at both the simplicity of the poem’s title and its first line, emphasising the poignancy of the word “sweet”, through a simple four-bar phrase introduction. The first two bars consist of an accompanied rising disjunct melodic 5th which becomes an important cell from which three melodic units are derived throughout the song. This is answered by a half-close cadence with added non-chromatic 9th and 4th notes (IV9 - IIIb4 in bars 3 and 4).

The simplicity of the accompaniment in verse one suggests the apparently simple observation of the poet - that love does change (in manner at least). This image is suggested through the use of simple diatonic harmony. Yet Milford is able to bring many touches of imagination to the unsuspecting ear. The subtle gentleness of added-notes and inversions creates further interest in the accompaniment. Texture also contributes to imagery in verse one and two. Taking verse one as an example, imagery created through textural devices includes the falling quaver notes harmonising with the melody in 6ths during bar 16 which decorates “strange We”, and the rising right-hand contour through a 7th to the supertonic in bar 18 decorating “love” and creating a climax for the concept of constant love - this rising contour employs a distinctive rhythmic figure which later becomes a repeated unit in the song. The texture in verse two is the same as that in the previous verse.

In verse three, two main features assist in suggesting the passing of time. The first is the change in the accompaniment, involving decorative quaver, semiquaver and dotted quaver/semiquaver figuration, while the second involves the use of an English cadence (Ab/Anatural), employing the quaver/semiquaver rhythmic unit, in bar 46. A piano trill depicts the image of fancy within the phrase “Nor even in fancy to recall” (bars 51-54), while the idea of memory recall is illuminated in bars 52-54 by falling quavers, perhaps suggesting a peal of bells. The image of pleasure - the climax of the verse - in the following phrase, “The pleasure that was all in all” (bars 54-58), is suggested by a rising dotted quaver contour, now in 3rds, accompanied by widespread, low register chords in the left hand.

The texture of verse four alters completely, reflecting not only its imagery but also the true meaning of the poet in this poem. This involves two important aspects which must have exerted a profound influence on Milford’s song-setting. Firstly, although the poet earlier stated “That love will change in growing old”, he is not referring to a human life-span but to the length of his love affair, a few months - April to summer - as shown in the lines “His little spring, that sweet we found, So deep in summer floods is drowned …”. Secondly, the memory of his first kiss is now forgotten, not, as everyone supposes, because love has faded, but because it is now overtaken by his superior current love - “bathed in joy complete”. Thus, the poem is a triumphant celebration of present love - and a most fitting subject to be dedicated ‘For my wife, with love, July 1933’. Milford heralds this important stage in the song through his performance direction ‘Very Broadly’ and use of forte, wide-spaced chordal accompaniment.

Also in verse three, the poet not only creates profound imagery but also employs word-play. Therefore the word ‘spring’ in the phrase ‘His little spring’ refers not only to the season but also to a well, a source. The sweet water of love is now drowned by summer floods in the phrase ‘So deep in summer floods is drowned’. In this context, then, Milford paints the words “deep” (bar 63) and “drowned” (66) through widely-spaced piano texture, involving the left-hand bottom octaves.

Use of the treble register in both hands of the accompaniment, and a dotted quaver/semiquaver rhythmic figure in 3rds in the left hand, illuminates the phrase “bathed in joy” in bars 68-69 through. Finally, the image of sweetness implied at the end of the final phrase, “How love so young could be so sweet”, in bars 70-74, is projected by the simplicity of the left hand moving once again into the treble register (for the now well-established but simple IIb-V-I progression) and the accompaniment ending on the tonic chord in the upper and brighter register.

Other examples of the interaction between musical features and text include the contrast between rising and falling contours where the former depict a pleasant image and the latter a dark image (for example rising in bar 10 for “kissed” and falling in bar 13 for “thorn”), and the rising disjunct 6th in bar 15 stressing “not”.

‘Love on my heart’ is the third song of this period which is influenced by the English ayre. In his poem of the same name, Bridges explains that love has descended on him and compares this to a process of nature - the dew refreshing flowers. The poem is a joyful love poem presented in religious terms. Milford employs an interesting rhythmical setting through a series of time changes in each verse, showing his dedication to the poet’s metre.

The tonic arpeggiated chord in the introduction (bars 1 and 2) is central to the entire song, representing love which has descended on the poet. It is the first suggestion of any relation with an ayre. After verses one and two (in which the melody is accompanied by four-part chords, two-part and three-part writing, the development of this song commences. Verse three (bars 37-48) is the climax of the entire song. Milford delays the entry of the voice in bar 37, and then shortens the phrase from its normal four bars in length to two bars with the new phrase entering to emphasis the poetic phrase “Nor was afore, nor e’er shall be” (bars 39-40) - again commencing on the off-beat. A further point of emphasis is Milford’s retention the original four-bar harmony from the two previous verses, superimposing the new melodic material on the original harmony and texture.

The fact that this verse serves as the climax is further emphasised by Milford creating (in bar 41) an effective anticipation of, and link to, phrase B (bars 42-44) by sounding the usual opening subdominant harmony one bar before the voice’s entry, thus forming a canon. This effectively highlights the poetic climax - “Nor any other joy than his” which employs supertonic harmony for two bars. The extension (bars 47-48) of the song’s final phrase forms a fine codetta, emphasising the words “to comfort me”.

The overall gentleness of the accompaniment reflects the poet’s comparison between love and aspects of nature such as dew and flowers. Milford constantly employs harmonic accented passing-notes, neighbour-notes and added-notes for word-decoration within the phrases “Love on my heart from heaven fell” (bars 3-6); “Soft as the dew on flowers of spring” (bars 7-9); “Now never from him do I part” (bars 20-23); “Hosanna evermore I cry” (bars 24-26); “Without him nought so ever is” (bars 37-39); and “Nor was afore, nor e’er shall be” (bars 39-41).

Finzi registered his approval on receipt of Milford’s settings of Bridges’ poems in the collection Four Songs with Piano Accompaniment, “The Bridges songs are lovely & I don’t wonder at Cuthbert Kelly’s enthusiasm. Nos 1 & 4 (‘So sweet love seemed’ and ‘Love on my heart’) seem to be the most obviously attractive, but they’re all equally fine & I can’t think how I’ve missed them all the five years they’ve been published” [2]. Milford was pleased, “I’m so glad you like the Bridges songs. Yes, 1 & 4 are the best, perhaps as good as anything I shall do” [3]. This final comment highlights the fact that Milford was completely unpretentious, if not damagingly self-critical, regarding his music and totally wrapped in self-doubt. He continued, “Now I am more ambitious still, one can only write as one feels, can’t one” [4]? Even in the 1940s, Finzi was still expressing his admiration for Milford’s ‘So Sweet Love Seemed’. He wrote to Milford, asking, “What about scoring So Sweet Love Seemed for strings” [5]? The following week, Finzi returned to the matter of scoring ‘So Sweet Love Seemed’ in relation to a performance at one of the Newbury Strings Concerts, “You certainly ought to score ‘So Sweet Love Seemed’ (and any of the others if you think they would score). We should certainly love to do it, for you can’t imagine how difficult it is to find contemporary songs for soprano and strings that are worth doing” [6].

Aside from Milford’s professional life, the 1930s also saw the happy arrival of Robin’s and Kirstie’s only child, Barnaby, in 1935. A happy marriage, Barnaby’s birth and profound friendships created an anchorage during which Milford composed the bulk of his main published songs. These years did not, of course, alter his temperament; they simply served as a buffer for his nervous state.

‘Cradle Song’, an individual song reminiscent of Warlock, is a setting of a five-verse poem by William Blake. The poem involves contrasts between innocent joy and sorrow, light and darkness, and sub-consciousness and consciousness.

In verse one, the poet establishes an innocent rocking image during the first three lines, with sorrow appearing in the fourth line. Having established such contrasts in the reader’s mind, Blake returns to the theme of innocence in verses two and three. In verse two, the speaker is merely a watcher; in verse three, he touches the treasured baby who smiles. Such smiling can be interpreted as either a subconscious awareness of the safety of being with a trusted adult or the existence of some mysterious secret motive for joy - perhaps, even, holy. Blake’s poetry was often inspired by mysticism and frequently prophetic in nature. In verse four, the darker aspect, first introduced in line 4 of verse one, returns. Less innocent thoughts are now insinuated as the baby sleeps, resulting in distressed awakening. Having changed the poet’s final line of verse four from “lightnings break” to “night shall break”, Milford omits Blake’s fifth verse and returns to the repetition of the third and fourth lines of verse one. This serves as a codetta to the song. The poetic imagery in ‘Cradle Song’is profound and is achieved through the poet’s thematic contrasts.

Similar to Ireland in ‘The Holy Boy’ and Warlock in ‘The First Mercy’ (1927) and ‘Cradle Song’ (1928), Milford employs a swaying crotchet/quaver figure and a dotted quaver/semiquaver figure in the painting of Blake’s poem. A particular feature in Milford’s song, however, is the many harmonic side-steps within its F major tonality.

Milford retains Blake’s four-verse format and constructs his song through the use of four repeating four-bar phrases - ABAB, CDCD, an interlude, and repeat of phrase B which serves as a codetta. Phrases A and B are employed in verses one and two while phrases CD form verses three and four. Apart from melodic variation, harmonic side-steps, chromaticism and gentle dissonance are responsible for development in this song.

After the initial gentle first phrase (images of supposed security of sleep and calmness of night are depicted through diatonic harmony, for example, chords I, Ib, IV, Ib in bars 2 and 3), the song starts to develop in order to encompass the opposite images in Blake’s poem (e.g. “joys” and “sorrows”). At the end of phrase A, the harmony moves from a dominant 7th to an A major chord at the start of phrase B (bars 5-6). This phrase, of course, mentions such aspects as “joys”, “sorrows” and “weep”. It therefore moves on to C# minor harmony followed by a D minor chord embracing a false relation (bar 7). In phrase C (bars 18-21) Milford suggests the “softest limbs” through the use of diatonic harmony over a pedal D. The repeat of phrase C (bars 26-29), however, develops by employing a series of sixths in the upper piano part, ending with pronounced chromatic on “sleep” (bar 29), possibly suggesting less secure sleep and safety as time passes on. The repeat of phrase D (bars 30-33) commences with gentle dissonance, suggesting the wakening heart, with the remainder employing stronger chromatic harmony to paint the phrase “Then the dreadful night shall break”. The wider piano texture in this phrase also assists in the drama of this phrase.

Milford continues to develop the imagery of his text by reintroducing a variation of phrase A (where sleep was secure) in the piano alone, perhaps suggesting the fact that the child may sleep securely for now as the sorrows are in the future. The composer may even be suggesting as the humming of the person rocking the cradle as a repeat of phrase B continues on, ending now with V-I closure on “weep” (bar 42).

In summary, Milford creates the images of supposed security of sleep and calmness through the use of diatonic harmony (e.g. chords I, Ib, IV, Ib in bars 2 and 3) and gentle chromatic shifts (e.g. an A chord in bar 6) and chords with non-chromatic added-notes (e.g.II7 in bar 12 and IC6 in bar 13). Further gentle dissonance is created by the use of chords with non-chromatic added-notes (examples include II7 in bar 12 and IC6 in bar 13 ), chords consisting of superimposed non-chromatic and chromatic intervals (examples include the chord on the second “sleep” in bar 6, the chord on “steal” in bar 21, and those on “shall break” in bar 33) and the false relation in bar 7 on the word “in”. Other prominent musical features employed in the interaction with the text include frequent word-decoration (e.g. “Little sorrows sit and weep” in bars 8-9), undulating contours (e.g. bars 4-5, representing dreaming, joys and night), angular melody (examples include “Little sorrows sit and weep” in bars 8 and 9 and “When thy little heart doth wake/Then the dreadful night shall break” in bars 30-33), legato writing, soft dynamics, and relatively close position chords.

It is interesting that Milford also depicts the child’s secret joy and smiles through use of both superimposed chromatic and non-chromatic intervals (bar 15). They are aspects of the most private part of the psyche and Milford acknowledges the fact that such dreams can be pure and innocent, and, on the other hand, driven by some dark force. The melody of ‘Cradle Song’is sustained through the use of a repeating melodic unit, consisting of a neighbour-note unit, which itself creates a swaying effect. This unit makes its first appearance in bar 2, consisting of the notes CDC, introducing the important words “Sleep, sleep, beauty bright”.

Numerous composers have employed the ‘Barcarolle’ rhythm in cradle songs (e.g. Gibbs in ‘Lullaby’) but Milford, in responding to Blake’s poem, has strengthened the development of his ‘Cradle Song’ through the dramatic and darker contrasts which paint the more sinister aspects of the text. The equivalent song of Gibbs continues its ‘rocking’ rhythms amidst a flow of evocative harmony while Milford’s tensions, created through dissonance, adds much to his song.

The next series of songs display the influence English folk-song (through modal implications, melody, harmonic movement by step and part-writing) and folk poetry (in terms of poetic themes and construction). ‘Elegy’ (1933) is dedicated to the composer’s wife, Kirstie. Having attended a performance of Finzi’s choral setting of Bridges’ poem ‘Clear and Gentle Stream’, Milford seeks Finzi’s advice regarding his own beautiful solo song, “I should value your opinion on my Elegy [‘Clear and Gentle Stream’] very much if you could bear to hear it when you come here - I’ve lost all confidence in knowing about my work now; I mean, if the ideas themselves (the essentials) are decent at all, or just awful.” [7]

Considering Milford as an equal, Finzi compared both settings of ‘Clear and Gentle Stream’ and came to a gracefully diplomatic conclusion, “The fact that we have both done settings and can listen to each other’s with pleasure, only helps to show the good sense of Blake’s ‘There’s no competition in Heaven”. [8]

‘Elegy’is a four-verse progressive-strophic song in which verse two is strophic until bar 33, when additional material is inserted; verse 3 contains additional material; and verse 4 is strophic. The twelve-line verses of Bridges’ poem have an elaborate rhyme-scheme, consisting of the following pattern: abba, cdcd, eeaa. This is employed in verses one, the strophic part of verse two, verse three and verse four. This scheme also assists in the effect of lilting forward.

The introduction consists of a triplet figure in the right hand of the piano, centred on the note B, against rolling 3rds in the left hand. It becomes an ostinato, suggesting the continuous flow of the stream. Thus, as in Schubert’s ‘The Brook’s Lullaby’, the introduction instantly sets the scene of a running stream. Milford’s song is, however, set in the Aeolian mode on E.

The introductory ostinato continues throughout most of the song but Milford is never prepared to confine his ideas to what the listener has come to expect. For example, from bars 7 to 10, he sounds a series of Ds in semibreves, perhaps hinting at a flattened 7th in the E Aeolian or suggesting the dominant of G. ‘Elegy’ is a nostalgic pastoral poem, reflecting on the transition of life. As the poet visits the stream, a flood of memories returns. He recurrently addresses the river with the phrase, “Clear and gentle stream”.

In the opening of verse one (bar 3), Milford takes up the poet’s challenge of personification by giving his opening phrase, “Clear and gentle stream”, a falling five-note melodic gesture (this falling gesture also suggests the downstream flow of the stream). Thus, the composer creates a conversation between the voice (the poet) and the ostinato (the stream).

The falling five-note gesture becomes central to the entire song not only through its imagery but also through its constant repetition in original and altered formats. Examples include a shortened format during the line “Known and loved so long” (bars 5 and 6) and an inverted disjunct format, when the melody leaps from D to top G, emphasising “heard” in bar 7 (the first climax of the verse) during the phrase “That hast heard the song”.

The conversation between the voice and stream continues until tension builds in bar 11. Here an altered chromatic form of the ostinato, in addition to melodic chromaticism, illuminates one of the central aspects of the poem - that life does not remain the same - explained in the phrases “While I once again/Down thy margin stray,/In the self-same strain/Still my voice is spent,/With my old lament/And my idle dream” during bars 11 to 17. The phrase “While I once again” shifts to the A Aeolian mode, while the phrase “Down thy margin stray” sequentially shifts to the B Dorian mode in which the next phrase, “In the self-same strain” remains. The phrase “Still my voice is spent,” is derived from F# minor and C major harmony, while the final phrases, “With my old lament/And my idle dream”, employ chromatic harmony (Bb, F, C min.7 and F min.7, Ab7, B min.).

Such writing seems to suggest a strong urge, and possible discomfort, on the part of the poet to retrieve those feelings which he experienced as a boy at the side of the stream. Does the poet’s reference to the ‘old lament’ imply his old song in which he expressed his feelings about the stream? However, the inevitable constant changing movement and nature of the stream itself undercuts the poet’s attempts to recapture the past, to fix a mood which has gone irretrievably.

The emotional effect of the stream on the poet is emphasised in the final statement of “Clear and gentle stream” in bar 18 through use of a sustained A minor (11th) chord, strengthened by contrary movement between the voice and upper right hand at the end of the bar. The effect is made more mysterious by the accompaniment failing to rise to top G in bar 19, as expected, but rather falling to the original ostinato pivoting on B and rolling 3rds centred on E - thus emphasising the emotional pull of the stream. Thus, the tonality/modality setting of this evocative poem is still not confirmed.

In the strophic part of verse two (bars 21-32)), features identified earlier illuminate the poet’s memories, including back eddies playing shipwreck with the leaves and the straying swans, as he sits where he used to sit - now, apparently, disappeared. Development in this song commences in the ‘progressive’ material of verse two (bars 33-37). The ending of the verse suddenly turns into a chromatic and restless section, possibly suggesting the formation of a pool through the cessation of the flowing stream. The piano ostinato ceases and is replaced by wide-spaced chromatic chords implying I-V (B major), V-I-V (A major) and V-I (G major) progressions. A sense of restlessness is created through the falling sequential harmony, resulting in a series of falling melodic sub-phrases.

It is in the “chosen pool” that the poet observes the fish lying in the cool water. This section also illuminates the poet’s present, and less pleasing, observance of the now straying swans and the motionless fish. Further disruption to the poet’s memories is painted through an alteration to the now-established rhyme pattern to include a new rhyme (e), now ‘forte’, during bars 36-37. If the tonal interpretation of the phrase-ending is considered in G, it, unusually, concludes with a IVb - III progression. This sees a return of a triplet figure, suggesting the original ostinato, which serves as the interlude between verses two and three. The ostinato is clearly not in its original form but is built upon swaying B minor and E major staccato chords. In verse three, use of a leisurely two-part canon between piano and voice in the non-transposed Aeolian mode suggests a return of the poet’s pleasant memories. This is achieved through the ‘colour’ of the Aeolian mode (created through its particular order of intervals) and the use of a leisurely falling melodic contour in the canon. The voice enters after the piano, both, appropriately, on strong beats but in bars 42-48, the canon is altered with the piano now following the melody.

Milford’s use of the Aeolian mode suggests an even deeper movement into the subconscious on the part of the poet. Melodic contours also contribute to this image. Use of the falling conjunct 5th melodic gesture for the words “Many an afternoon” is particularly poignant in bars 39-40, while the contour continues to fall through a triadic structure, decorating “summer day”. The melody has now moved to a lower register and remains there, depicting the poet lying dreaming.

The poetic imagery in each of the lines “Dreaming here I lay/And I know how soon/Idly at its hour” is characterised through Milford’s use of a sequential neighbour-note melodic structure, employing a dotted crotchet/quaver figure, centred on low D and C. This swaying melodic structure also suggests overhead leaves, mentioned in the previous verse, swaying in a gentle breeze. The haunting image of a “deep bell” in bar 46, during the lines, “First the deep bell hums/From the Minster tower”, is created not only through use of a canonic falling melodic contour in the accompaniment, but also through use of an ‘open’ F major chord in the left hand of the accompaniment. The former creates an echo-effect of the bell.

The arrival of evening in the phrase “And then evening comes” is illuminated through a rising melodic 5th and swaying crotchets in 6ths (bar 49) on an E minor chord. These also hint at the passing of time which results in eventide. The image of evening “creeping up the glade” is created by a continuation of the swaying 6ths but now over G major harmony in bar 50. The word “glade” is illuminated by an F#m9 chord in bar 51. These features are set against ‘poco cresc.’ and ‘mezzo-forte’ markings which assist the images to enfold.

The poetic climax of verse three must surely be this section, heralding the gradual arrival of evening and, ironically, culminating with its own climax - darkness. In the phrase “With her length’ning shade” (bars 51-52), the image of evening creeping onwards is now dramatically presented through rising quintuplets leading to D# minor harmony, allowing triplets to rise through the bass register. The image of declining light is further strengthened by a falling melodic contour on “length’ning shade”, followed by rolling quavers, based on first inversion G# minor and F# major triads, which continue the image of progressing time.

Milford illuminates the uplifting imagery of the phrase “And the tardy boon/Of her bright’ning moon” (bars 52-53) through rising triplet C# minor arpeggiation (in the bass register rising), resolving on an F# minor chord. This material is sequentially derived from the setting of the words “… length’ning shades”. The image of the “bright’ning moon” is depicted through the use of ascending 6ths in the right hand over G major harmony, ending on an E major 7th chord in bars 54-55. Musically, verse four returns to the strophic material of the song, while the poet returns to present consciousness. In this verse, identical features to those used in the interaction between music and text during verse one illuminate the poet’s final address to the stream. He expresses his contentment with his thoughts and dreams of by-gone days.

Milford retains the air of nostalgia right to the end of this song. The final appearance of the falling 5th unit and the phrase “Clear and gentle stream” is derived, as in verse one, from an A minor (4th/7th) chord. The phrase concludes with contrary movement between the voice and upper right hand, as before, during bar 72 but now the piano top F# rises to top B in bar 73. Implication of the Aeolian mode on E returns in bar 73 with the reappearance of the piano swaying triplet figure. The song, finally, ends on an Em7 chord (or G major first inversion chord), with use of the upper register of the piano suggesting the sparkling image of the clear stream.

‘Elegy; is the first of Milford’s songs to employ a true and developed dialogue between voice and piano. The gentle rhythms throughout ‘Elegy’ also contribute to the idyllic setting painted by Bridges. The texture is quite uncluttered, giving the impression of clarity and gentleness. This becomes all the more poignant when ‘Elegy’ isconsidered alongside other composers’ songs such as Schubert’s ‘The Brook’ or Gurney’s ‘The Boat Is Chafing’ (1920). In these cases, the flowing water is depicted through a thick texture of flowing semiquavers and all manner of accidentals. Milford seems to have achieved much more with his lighter textures.

Dedicated to Gerald Finzi, ‘The Colour’ shows Milford at the height of his powers in song-writing and illumination of poetic imagery where folk-tale is set to folk-like music. The poem captures the true essence of Wessex folk-tales with which the poet was so familiar. Gittings connects Hardy’s family home at Bockhampton cottage and the “rhythms of folk-songs from his father and mother” to poems such as ‘The Colour’. He states, ‘One West Country folk tune, which he had already used for a poem in the early months of the war, provided the basis for two more poems … ‘Meditations on a Holiday’ and ‘The Colour’. [9]

In the poem, the questioner attempts to find an appropriate colour for his lover which will represent the current stage of their love. She rejects his first four suggestions. In verse one, the poet considers the colour white, but as this is generally associated with weddings, that will not do. In verse two he suggests red, but that is for soldiers, while in verse three the colour blue is also unacceptable as is green in verse four. Blue is for sailors, while green is for Maying. In the final verse, we find that it is only black which is suitable due to its association with mourning. Thus, throughout the poem, Hardy uses

colour to hint at an unstated story through the recurrent poetic technique of question and answer.

Although ‘The Colour’is a five-verse song in strophic form, Milford illuminates the text through a series of variations in the accompaniment of verses two, three and four, with verses one and five both being unaccompanied. Each verse consists of eight melodic phrases (A-H) set in the E Aeolian mode (although verses two and three commence on a G major chord).

After a Mahlerian-type introduction (bars 1-2), the simple folk-style melody of ‘The Colour’ profoundly reflects the nature of Hardy’s folk-poem. The melody is organically derived from three melodic units and three rhythmic units. The first melodic unit consists of a repeated note figure (e.g. bar 3) coupled to the first rhythmic unit (a dotted crotchet/semiquaver figure, e.g. bar 5), while the second melodic unit consists of a rising 3rd (e.g. bar 4). The third melodic unit consists of a falling 4th and is coupled to the second rhythmic unit - a crotchet duplet figure (e.g. bar 6). The third rhythmic unit consists of a crotchet pattern (e.g. bar 4). These rhythmic units also appear in the accompaniment, acting as a unifying technique.

The melodic climax of ‘The Colour’ is the top G in each verse. Milford makes full use of this climax on two occasions within each verse. The first highlights the colour under consideration: white (bars 4), red (bar14), blue (bar 25), green (bar 33) and black (bar 43). The second decorates the subject associated with the colour: weddings (bar 7), soldiers (bar 17), sailors (bar 28), mayings (bar 36) and mourning (bar 46).

‘The Colour’ abounds with musical imagery, as a result of each verse being handled quite differently in terms of accompaniment. The differences in texture between verses 2, 3 and 4 with accompaniment are derived from variations in harmony:

Harmony Phrase A - E (E Aeolian Mode)

| Verses |

Phrase A |

Phrase B |

Phrase C |

Phrase D |

Phrase E |

| 2 |

III Vb III |

I VI IIIb |

VI IV7 V I |

IVb IV I |

VIIb III V III |

| 3 |

III V |

VI III |

VI V I |

IV VI I |

IV I III IIIC |

| 4 |

--- |

--- V |

VI IIIb |

IV I |

IV V6 |

Harmony: Phrases F - H (E Aeolian Mode)

* = superimposed unrelated intervals

| Verses |

Phrase F |

Phrase G |

Phrase H |

| 2 |

I VI V III |

VII V IV7 |

--- |

| 3 |

VI III III Ib |

IV VI V |

** IV III |

| 4 |

II7 I7b |

IVC --- |

IV I |

Following the shock of the introduction, with its immediate tension after the tonic triad and its rhythmic patterns, the unaccompanied voice in verse one reflects both the earnestness of the man’s question and the negativity of the girl’s response. It also suggests the image of a folk-singer telling this tale. The straightforward melody speaks for itself and allows the simple message to be clearly delivered.

Verse two (bars 13-20), concerned with the colour red and soldiers, has a march-like, but rhythmically displaced, chordal accompaniment, creating a military image through its regular harmonic rhythm. A three-part accompaniment to the melody in bars 17-19 helps to emphasises the phrase “Red is for soldiers, Soldiers, soldiers, Red is for soldiers”. In response to the military reference, the opening fanfare appropriately returns as the interlude between verses two and three but now sounding an octave higher - higher, indeed, than the pitch of a real fanfare.

Verse three (bars 24-31) is concerned with the colour blue and sailors. The left hand rising quavers, derived from sustained harmony, in bars 24 and 25 hint at the wash of the sea, while the falling dotted crotchet/quaver rhythmic figure (derived from the vocal melody) in the right hand during bars 28 and 29 suggests a sailors’ dance. The two-part coupling of the melody in the right-hand of the accompaniment during bars 30 and 31 emphasises the phrase “Blue is for sailors, And that won’t do”, while the rising and falling quavers which accompany these lines most certainly reflect the rise and fall of the tide. Never wishing to be predictable, Milford does not employ an interlude between verses three and four. This, however, may reflect the growing tension caused by the succession of suggestions and rejections.

His inventiveness and sense of development/variation are seen again in verse four (bars 32-39) where the melody commences unaccompanied and is then accompanied by triadic quaver figure in the right hand, derived from sustained harmony (bars 33-35), perhaps suggesting May-tide dancing. The dancing is further illuminated by a syncopated figure of 3rds in both hands during bars 36 and 37, again derived from expanded harmonic rhythm. The poetic conclusion to this verse is emphasised by a right-hand trill, harmonised by a submediant chord in its last inversion.

The interlude (bars 40-41) to the final verse is that employed between verses one and two, giving some degree of unification. Verse five (bars 42-50) deals with the colour black and mourning. Milford does not suggest a slower tempo nor, indeed, a minor tonality. The melody is, however, once again, unaccompanied - suggesting less flamboyance. Milford appropriately paints Hardy’s question (“Then?”) by an off-beat note slurred over to the next bar (bars 42-43).

Milford acknowledges Hardy’s poetic technique of question/answer by ending the question, melodically, on the principal (E) and the answer on the 3rd degree of the mode (G), both employing the crotchet duplet unit. Milford also acknowledges Hardy’s poetic forward progression through the colours and their associations (beginning with the lightest, or least colourful, and progresses through the brightest colours to the darkest or most colour-denying shade). He, thus, commences his song with an unaccompanied verse and then increases the level of complexity in the accompaniment during the succeeding verses as they progress through the colours, ending with a final verse which returns to the unaccompanied voice-line of verse one. Dramatically, at the conclusion of the last verse, the composer once more sounds the opening fanfare-effect against the final sustained note of the melody (bar 49). It is now in the bass register, perhaps suggesting a haunting recall of this sad tale of love.

Use of the Aeolian mode on E reflects the dark shadows which surround this tale. The effect of this mode is constantly emphasised by the contrasting G chord opening of verses two and three, four and five. The final bars, however, leave the listener in little uncertainty regarding the overall tonic. The more unusual introduction could well have its origins in the introduction to Gibbs’ ‘The Mad Prince’. Here rising E minor semiquaver figuration resolves on an E minor, augmented 6th chord, suggesting the prince’s madness. The difference between the two songs lies, however, in the fact that Gibbs uses this introductory throughout his song to suggest the continued madness of the prince. Milford, on the other hand, re-employs his introductory material again as a codetta.

‘Tolerance’ is a progressive-strophic setting of Hardy’s poem which is concerned with philosophy, will power, shadows of the past and tombs. Milford explained that it was written after “visiting Hardy’s burial-place and birthplace”. [10] An air of mystery is instantly created by an introductory piano octave suspended dominant (Bb). Against this background, the melody and piano interact in a dialogue which involves ‘mirrored’ neighbour-note structures (EbDEb in bar 1 and BbCBb in bar 3), melodic growth centred around the note Bb, falling piano figuration, further melodic growth involving two falling sets of disjunct movement (3rds, then 5ths), all ending with an interrupted cadence which, of course, leads on to the next verse.

Milford subtly reminds the listener of the all-important musical phrase from bars 2-3 (which presents the phrase “ ‘… foolish thing’, said I”) in the piano bass during bar 7 before verse two commences (perhaps serving as a reminder of its textual importance). Here (bar 8), the haunting octave Bb is heard again beneath which the voice is coupled in the piano at the octave, starting on a first inversion Eb tonic chord (bar 8). The speaker continues his reflective mood and goes on to realise that he could have spared himself a great deal of unhappiness. He also continues the image of reflection through a repetition of the melody from the previous verse but now reflects the poet’s next step in his thoughts - realisation - by the introduction of a more prominent chordal texture (bars 10-11). The important word “wise” (bar 12) is at first unaccompanied, followed by a bass line alone entering in the piano. The poetic climax of the verse appears when the narrator states his realisation, “I might have spared me many sighs”. Milford responds with chromaticism and word-painting of the word “many” through the use of triplets on the final two notes Bb-Eb.

Development of such figuration becomes an important textural device during the remainder of the song. Triplet figuration (on submediant, dominant and a return to submediant harmony) in bars 15 and 16 now serves as a link to verse three. This material is reminiscent of a Mahlerian fanfare with the rolling triplets seeming to suggest a brighter and more positive message in preparation for the next two verses (they also become more important later in the song - suggesting a “theme” motif).

Verse three (bar 17-23) develops melody, harmony and texture. The verse commences on sustained subdominant harmony using the neighbour-note structure (now transposed to CBbC). With the identification of qualified “happiness” the melody now develops to include new material involving a higher register and broken, chromatic chordal writing.

Milford links stanzas three and four in order to permit the current level of tension in the song to continue. The falling bass line reintroduces the necessary Ab to return the song to Eb major stability.

Verse four (bars 23-29) continues to reflect on the thought of comfortless. Now the opening neighbour-note structure (C, Bb, C), again on submediant harmony, is decorated by harmonisation in 3rds, possibly developed from the rolling thirds in bar 16 (Milford possibly wished to create a connection from the poet’s past refrained behaviour to his present happiness). The approach to the climax of the song commences when the second and third syllables of “remember” are illuminated by rolling left-hand triplets in 3rds. The poet’s mastery in restraint is painted not only by use of an off-beat rhythm in the piano bass (bar 24) but also by fanfare-type material on Bb and F chords (bars 25-26). The image of gain is achieved through further development of the melody involving use of top F in bar 27 and a decoration of falling 3rds - also on Bb. This constitutes the first half of a climax in this verse.

The second half of the verse’s climax consists of the phrase “And for my tolerance was disdained” (bars 27-29). Milford illuminates these words by use of further high register, chromaticism, wider texture, increased dynamics and gentle dissonance, closing the phrase with an expected cadence in Bb major. However, painting the image of disdain, Milford tonally destabilises the song through chromaticism in bars 28-30 (involving the notes Gb and Db). Indeed implications of Bb major and Eb minor now become apparent (bars 28-29 and 29-30 respectively). However, by the middle of bars 30, tonal stability resumes.

In the final verse of the poem, the poet sees a tomb at which he would not dare to linger had he yielded to the temptation he is now so delighted to have avoided. Milford in his final verse (bars 31-37) returns to the opening material of verse two for phrase A, strengthening the unity of the song. He alters the bass line to a lower pitch in order to suggest the depth of the tomb, moving from G, to F and Eb in bars 32-33. Similarly, a Bb minor chord is used to paint the word “bent” in bar 33. The triplet figuration is now developed further to involve crotchets (bar 34) but returning to quavers on the dominant chord in bar 35. The prolongation of this dominant harmony is responsible for an evocative ending to this song involving the final phrase, “To linger in the shadows there” (bars 35-37) and the codetta (bars 38-40). Milford now presents a new and poignant melodic musical phrase, characterised by disjunct movement. The musical process appropriately slows down in order to create the daunting images of lingering and shadows. Milford continues his organic process right to the end of the codetta in terms of harmony and texture. The harmonic substructure is masked. Triplet quavers return on further dominant harmony (bar 38), progressing to chord VI where the upper piano now takes the earlier off-beat figure in thirds (bars 38-39). The harmonic closure is finally heard through the use of chord Ib sounding at the end of bar 39. Milford, however, is not yet finished with his listener as he concludes with an F minor chord, possibly suggesting the overall mystical character of the text, as a separate identity or as part of an interrupted cadence.

Turning now to dramatic and ballad-type songs, ‘To Sincerity’ employs a more progressive musical language. Milford’s setting of Hardy’s six-verse poem makes ‘To Sincerity’ the largest and most dramatic song to date through its use of juxtaposed sections and more expansive tonal scheme.

In the poem, ‘To Sincerity’, the poet considers the value of reality and different form of opposites. He is sceptical of the effects of the modern age on man’s views and values. Milford responds to these poetic aspects through the use of a varied series of musical features, including long and short durational notes, conjunct and disjunct movement, small and large intervals, gentle and angular contours, large and small melodic ranges, tonality, modal implications, light and thick textures, diatonic harmony, and chromatic harmony - all underpinned by the series of juxtaposed diverse sections. Organic development involves a triplet rhythmic unit.

Milford sets ‘To Sincerity’in three main sections, each containing two poetic verses. In addition, there are also interludes and a codetta. The songis rhapsodic in character due to its harmonic and chromatic wanderings, and use of tonal and modal implications. Creating a new form for Milford (through the juxtaposition of diverse sections), these features are shown below:

| Hardy’s Verses |

Milford’s Sections |

Bars |

Tonality/Modality |

Harmonic Substructure |

| 1 |

1 (with a 3-bar introduction) |

1-12 |

F# Aeolian |

Chord I (bar 1)

Chord V (bars 8/9)

Chord I (bar 10) |

| 2 |

1 |

13-15

17-18 |

E major Implication

G minor |

Chord I (bar 11)

Chord V (bar 12)

Chord I (Nil)

Chord I (bar 17)

Chord VIIb (bar 17)

Chord I (bar 18)

Chord V (bar18) |

| |

Link |

19 |

F minor |

Chord I (bar 19)

Chord V7 (bar 19)

Chord I (Nil) |

| 3 - 4 |

2 |

20-33 |

Eb minor Implication |

Chord I (bars 20-26)

No V-I closure |

| |

Link |

34-36 |

F# minor Implication

E major |

Chord I (bar 34)

Chord VIIb (bar 34)

Chord Ib (bar 35)

Chord V7 (bar 36) |

| 5 - 6 |

3 |

37-49 |

E major |

[Chord VI] (bar 37) |

| |

Coda |

58 |

E major |

Chord I |

The table highlights Milford’s harmonic and tonal/modal diversity within the three juxtaposed sections. The melodic and textural interest in the song is underpinned by tonal uncertainty. The song commences in the F# Aeolian mode, meanders through various implications and resolves in E major for the final painting of the word “sincerity”, totally new horizons in Milford’s song composition.

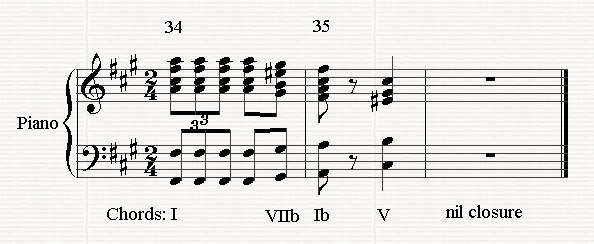

Verse 2 - G minor substructure

The substructure of the link between verses 4 and 5 (between sections 2 and 3):

Such juxtaposition of sections and wide tonal span had been employed by composers whose songs would probably have been known by Milford. These include Martin Shaw in ‘Annabel Lee’ (1921), Gurney in ‘By A Bierside’ (1916) and Finzi in ‘The Phantom’ (1936).

The introduction (bars 1-3), reminiscent of that of ‘Love on my heart’ in its use of bass arpeggiation, presents a falling melodic gesture derived from the progression

I-V-IV-V-IV/Ib. This gesture presents a triplet rhythm which becomes a repeating rhythmic unit throughout the song. The gentle image created by the simple texture of the introduction suggests the uncluttered simplicity of bygone days.

Development commences at bars 11-12. Here, despite the anticipated modulation to E major, the song moves through various anticipated but, in fact, non-employed V-I progressions (i.e. F# minor in bars 13 and 15, E and D majors in bar 14, and F major in bar 16. The climax of this verse on “faiths” anticipates a modulation to G minor. Such fast-moving harmonic rhythm contributes to the idea of turbulence.

Verse three simply lifts the song on to a different plane through the sudden appearance of an Eb minor chord (bar 20), perhaps suggesting the unpredictability and freshness of youth. Indeed, the extended ‘tremolo’ effect in bars 20-26 contributes to this image. This verse certainly demonstrates the fact that the textures of this song are clearly linked to Hardy’s poem. For example, Hardy writes, “But custom cries: ‘Disown it:/Say ye rejoice, though grieving,/Believe, while unbelieving,/Behold, without perceiving!’ ”. Milford illuminates such strong commands in bars 27-33 through ‘agitato’ and ‘declamando’ markings (bar 27), detached chords (for example 28-29), and alternating bars of an accompanied and unaccompanied voice-line. The two poetic phrases in bars 28-31 (“Say ye rejoice, through grieving/Believe, while unbelieving,) consist of two opposing ideas, positive and negative respectively, creating a statement and answer technique. The former is emphasised through an unaccompanied voice-line, while the latter is highlighted, ironically, by an harmonic fanfare-effect. The phrase “Behold, without perceiving” is effectively illuminated through the decoration of the second syllable of “without” in bar 32 with a semiquaver falling melodic contour.

The link to verse five, quite unexpectedly, returns the song to the ‘sharp’ side with the song continuing to move through numerous chromatic side-steps (e.g. C major 7 moving upward to an Eb major chord (bars 44-45). The fall to a Db chord on the word “better” (bar 46) creates quite seductive word-highlighting. The triplet motif is further developed from bar 49. Here, the penultimate phrase of the song (“And Life its disesteeming”) is painted in bars 49-51 through falling triplet thirds based on A and D chords (similar to semiquaver figuration employed by Gurney in ‘Spring’ during the phrase “The palm and May make country houses gay”), leading to a resolution on a sustained open D chord. Milford leads the listener away completely from any form of tonal stability through the sounding of a D minor arpeggio in bar 54 before sounding the unaccompanied final phrase (“O sweet sincerity” in bars 55-56). It is only in the final two bars that Milford reveals his tonal thinking by resolving on an E chord, itself predicted from the B chord at the end of bar 12. Harmonically and tonally, this song has consisted of a series of anticipations. These perhaps, more than any other feature employed in the song, reflect the overall depth of the message of Hardy’s poem - expected and deep sincerity. Milford employed in ‘Tolerance’ this form of ethereal ending where he concludes the song on a chord other than the tonic. Clearly, the end of ‘To Sincerity’ is somewhat distanced from the opening F# implied ‘tonic’.

‘To Sincerity’ is perhaps one of Milford’s most engaging songs through its use of defined sections. Gibbs and Finzi both employ this technique, for example, in ‘The Oxen’ and ‘Summer Schemes’ respectively.

Like Finzi, Milford was profoundly inspired by Hardy. He stated, “Of course it’s Hardy too who is my favourite writer, whose poems I sent home for almost as soon as war broke out, who still remains my greatest literary solace" [11]. The composer acknowledged Finzi’s influence at the beginning of ‘The Colour’ by inscribing the following dedication, “For Gerald Finzi, whose own settings of Hardy are at once my delight and my despair.” [12]

Milford gives Finzi prior notice of the dedication in writing, “One of the songs is for you, I’ll send you a copy when they’re out [printed]” [13]. On Christmas Eve 1938 Finzi writes to thank Milford for his Christmas present - copies of the Four Hardy Songs:

I really don’t see why I should not be allowed to say ‘thank you’ for something appreciated, not only the songs as music, but also what you have written on No 2 (‘The Colour’). If one can write it without being considered sentimental, it really rather moved me (which is a thing I’d rather write than say) & I think it’s a lot to come from a pretty well known composer [Milford] to one who is not [Finzi]. Anyhow, appreciation (& criticism) from people whose work I admire is the only sort that gives me real pleasure, so you’ve given me a proper Christmas present! [14]

Neither Kirstie nor Finzi was confident about the entire set of Hardy songs, “I think Kirstie will soon get to like them. Perhaps not No 1 (‘To Sincerity’), which doesn’t seem quite finished & digested (‘realised’ is the jargon, I believe) but No 2 & No 3 (‘The Colour’ and ‘If it’s ever spring again’) seem clear enough for anyone & jolly good tunes too. I think No 4 (‘Tolerance’) is a real beauty, much in my mind at the moment, & gets right inside Hardy’s grave & gentle mood.” [15]

Finzi’s judgement has been borne out as No 1 is the least known song of the set and was not published in the main book of Milford’s songs.

‘I will not let thee go’, also written in 1939, is the last of Milford’s published songs. Dedicated to John Goss, a well-known singer of the day, this songis a setting of Bridges’ seven-verse dramatic love poem. Forming a gateway to the more developed language of the unpublished songs, ‘I Will Not Let Thee Go’ is an important song in the composer’s output.

In the poem, the poet raises with his lover various reasons against, and various conditions for, allowing her to leave him, thus ending their month-old affair. In the first verse, he questions their month-old relationship being simply acknowledged in a single, presumably farewell, kiss. In the second verse, the poet suggests a complete incompatibility between his lover’s words and actions which now belie her wishes. In verse three, the truth of their love has been witnessed by the daylight, while in verse four, the stars have been witnesses. In verse five, the constant lovers have been at odds with the changeable moon. In verse six, the flowers’ willingness to be plucked by the lovers is the reason given against the break-up and in the final verse, the poet argues that, due to all the earlier reasons, he has too great a case against their separation. The poet arrives at a firm conclusion and states “I have thee by the hands, And will not let thee go”.

A rising tonic A minor triad, ascending through chromaticism to form a complete arpeggio (ACEA), introduces this turbulent song. Milford employs this gesture throughout (organically developing through transposition) to paint the poet’s frequent dogmatic statements “I will not let thee go” (bars 4-5, 11-12, 14, 55-56); and “I have thee by the hands” (bars 61-62). Constant melodic and harmonic chromaticism, high register notes and falling sequences paint the urgency of the poet’s message in verse one.

Development commences in verse two after the opening arpeggio phrase (still suggesting A minor). Gentle quaver figuration on E minor harmony (over a pedal E) paints the phrases “If thy word’s breath could scare thy deeds/As the soft south …” (bars 15-17). Instantly falling semiquaver figuration on G minor(7), F# minor (7) and Eb major harmony paints the image of feathered seeds being tossed (bars 18-19). The opening arpeggio gesture is not now retained to paint the poet’s constant determination. Rather, new chromatic material suggests the phrase “Then might I let thee go” (bars 20-21).

Verse three commences with the rising arpeggio gesture now on D. This verse employs larger homophonic writing with a Bb minor chord commencing with the phase “Had not the great sun …” (bar 24). The phrases “Or were he reckoned slow/To bring the false to light” (bars 25-27 are wonderfully illuminated by Eb minor, D major, Eb minor, Ab major, F minor and G minor harmony with an equally effective melodic ascent. The movement from G minor harmony (painting “light”) to a C# minor (7) chord (bars 27-28) suggests a period of reflection on the part of the poet before he utters the phrase “Then might I let thee go” (bar 28). Equally, the ending of verse three with a high register monotone (top E) in quasi-recitative style (marked meno mosso. senza misura) is powerful.

For the opening and closing lines of the next two verses (verse four and five), Milford deviates from the arpeggio-based gesture. In verse four semiquaver/triplet demisemiquaver figuration over a repeating pedal A gently paint the “stars which crowd the summer skies” (bars 30-33). Suggesting a modulation to D minor, the harmony pivots between dominant and tonic harmony. The final phrase (“I dare not let thee go”) in bars 36-37 is dramatically painted through a ‘gap and fill’ melodic structure which moves through G major, F major, E major and A major harmony.

Having returned to A minor, rising demisemiquaver bass figuration represents the rising moon (bars 39-45) while syncopated added-note chords are used for the poet’s comments on the moon (i.e. “rising late in bar 41 and setting “too soon” in bar 43). The conclusion to verse five and the one-bar interlude present, and prolong, dominant harmony.

The C minor (6) harmony at the opening to verse six (bar 47) thus comes a surprise. Moving to B minor and A major harmony, the verse opens in the upper melodic register suggesting near-desperation on the now well-known words “I will not let thee go” (bar 47) Rising and falling first inversion chromatic triads set against A major arpeggiation and neighbour-note figuration suggest “young flowers” (bars 48-52). The conclusion to this verse presents the most dogmatic phrase “I cannot let thee go” (bars 53-54). Here the harmony starts to return the song to D minor through prolongation of the A harmony and use of dramatic figuration (including contrary movement in the piano).

Milford now ceases any further development in the song by returning to the rising D minor gesture used for the opening of verse three. The crux of the poet’s argument (“I hold thee by too many bands”) is now painted using sequential falling fourths in the melody with the word “too” being firmly accented. Milford paints the word “bands” through the use of D major and B minor harmony, followed by a resolution on E major harmony. The structure is now set for the final statement of tonic harmony which Milford appropriately sounds at the poet’s final statement of resolution, “I have thee by the hands/And I will not let thee go” in bars 61-63.

Although cast in the key of A minor, Milford uses his harmonic language to advantage in this song in terms of harmonic rhythm, chord-types and complex harmonic movement. Examples of sustained harmony includes the prolonged E minor harmony in bars 15-18 creating the texture in the comparison between the lover’s breath to the “soft south” winds; and the sustained harmony in bars 30-33 painting “The stars that crowd the summer skies”; the E major harmony throughout verse five.

Finally, the wide range of dynamic and tempo/expression markings add to the drama of this song: forte, mezz-forte, crescendo, fortissimo, piano, diminuendo, mezzo piano; subitato, senza rit., poco allargando, non troppo rit., andante appassionato, cantabile, poco tranquillo, stringendo, animato, marcato, meno mosso, senza misura, espressivo, poco agitato, dolce, una corda. This song, alone, shows Milford’s development in the use of ‘shaping forces’. From the early songs through to the songs of the late 1930s, there is a definite increase in the number and range of expression employed in the illumination of texts.

References

1. Hold 2002: ‘Parry to Finzi’ p103

2. Finzi letter to Milford, 29 June, 1938

3. Milford letter to Finzi, 2 October, 1938

4. Milford letter to Finzi,

5.

Finzi postcard to Milford, 10 February, 1942

6. Ibid

7. Milford letter to Finzi, unknown, 1939

8.

Finzi letter to Milford, unknown date May, 1939

9. Gittings: “The Older Hardy”, 1978, p 253

10.

OUP: “Book of Songs”, 1942, p 42

11. Milford letter to Finzi, 21 October, 1939

12.

Milford song collection ‘A Book of Songs’, 1942

13. Milford letter to Finzi, 17 September, 1938

14.

Finzi letter to Milford, 24 December, 1938

15.

Ibid

© COPYRIGHT 2009 Peter Hunter

All songs discussed are obtainable from Animus Publications.

Milford home page

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews