|

Mahler's Song

Cycles

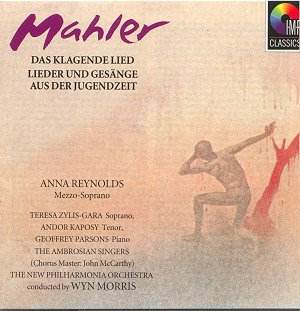

Das Klagende Lied "Das Klagende Lied" ("The Song of Lamentation") is Mahler's opus 1. He wrote it in 1880 at the age of twenty, just two years after leaving college. It's a cantata originally in three parts and based on stories by the Brothers Grimm and Ludwig Bechstein. Part 1 "Waldmarchen" ("Forest Legend") tells of brother murdering brother in a dark forest. Part 2 "Der Spielmann" ("The Minstrel") shows a minstrel finding a bone belonging to the murdered brother that he makes into a flute that sings human words when played. Finally in Part 3 "Hochzeitsstuck" ("Wedding Piece"), the minstrel goes to a wedding feast in a castle where the murderous brother is about to marry a beautiful Princess. The minstrel plays the bone flute, through it the dead brother reveals the truth, and the castle falls to the ground. The only other work of Mahler's to end like this in total catastrophe is the Sixth Symphony. "Das Klagende Lied" was not performed until 1901 by which time Mahler had revised it, a revision which included deleting the whole of Part 1, "Waldmarchen". The reasons for this are unclear. Maybe he felt dramatically Parts 2 and 3 work better alone. Maybe at the back of his mind was the death of his own brother Ernst in 1874. Did Mahler feel subconscious guilt at his much loved brother's passing and exorcised his feelings in some way by writing this work? Then, later on, he shied away from telling the world through "Waldmarchen"? Whatever the reasons, for many years "Das Klagende Lied" was performed with just Parts 2 and 3, but "Waldmarchen" turned up again in the 1970s and now the whole work is performed with all three parts. This is, of course, going against Mahler's wishes but the listener at home can choose not to play "Waldmarchen" if they feel any scruples. Ideally if "Waldmarchen" is heard at all, it should be alongside the original orchestration of Parts 2 and 3 prior to the revision which removed it. That too is now possible.

For performances that include "Waldmarchen" my favourite is the one by Simon Rattle on EMI (5664062) Amazon UK . This is less well recorded than some but is similar to Morris's in having a superb sense of drama and attack in the animated sections and a fine sense of the darker shadows. Alfreda Hodgson and Robert Tear are also among the fine soloists too. Better recorded and almost as compelling is Michael Tilson Thomas on BMG (09026685992) AmazonUK but, for three part versions, my advice is to go for Rattle. For me Tilson Thomas is a touch self-conscious, less aware that this is a young man's work. I mentioned that it is now possible to hear the three-part version with Mahler's original arrangements for Parts 2 and 3 - in effect hear "Waldmarchen" in its correct context. The first performance of this score took place in Manchester in 1987 by Halle Orchestra forces conducted by Kent Nagano and that performance is now available on Erato (3984216642) Amazon UK. It is of great interest, not least for the slight differences in instrumentation and the use of boy soloists at strategic moments. However, I don't feel Nagano quite has the feel of Mahler's special mix of Wagnerian-influenced texture along with his own early style and I think we await a better recording of this early version. I heard a splendid broadcast of the piece conducted by Rafael Fruhbeck de Burgos and maintain hopes that one day he might be allowed to record it.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Mahler's orchestral settings of individual poems from the anthology "Des Knaben Wunderhorn" ("The Youth's Magic Horn") by Armin and Brentano are crucial to our understanding of his art. Not only do they bear an intimate relationship to many of his symphonies, especially 2-4, they are small masterpieces in their own right. Then, as a sequence, they form a body of work of equal importance to that of any of the symphonies. All but two were written between 1892 and 1896, the remaining two in 1899 and 1901. The character of each is reflected in the orchestration used so great care must be taken to understand the words being used on every occasion. These poems appealed to Mahler for the same reason they appealed to so many of the time: nostalgic yearning after lost innocence, though Mahler's settings are unquestionably of his own time. Broadly there are three groups, or types, of song. Firstly the military songs which contain marches and the imagery of soldiers and warfare (Revelge, Der Tambourg'sell, Der Schildwache Nachtlied, Wo die schonen Trompeten blasen) bringing out memories of Mahler's childhood living near barracks. Next there are the love songs of varying kinds (Verlor'ne Muh, Trost im Ungluck, Das irdische Leben, Lied des Verfolgtem in Turm, Rheinlegendchen, Lied des Verfolgtem in Turm). Lastly humorous songs covering various situations with wit, irony and sarcasm (Wer hat dies Liedel erdacht?, Lob des hohen Verstandes, Fischpredigt.).

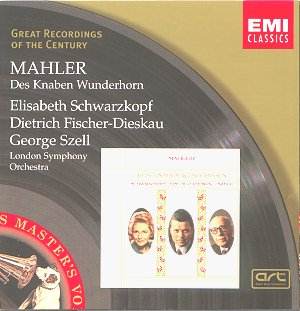

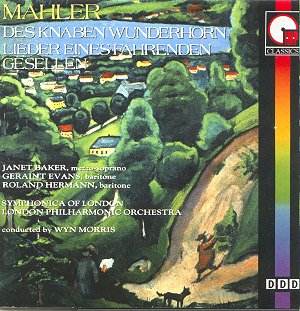

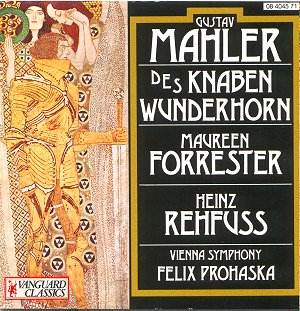

For me there are three truly great recordings of this collection for consideration. Recordings that, because of the contributions of conductors and singers, stand them head and shoulders above other versions. They are conducted by Wyn Morris, Felix Prohaska and Georg Szell. Other, more recent, versions under Haitink, Bernstein and Abaddo have virtues too and would grace any collection, but I'm going to leave them on one side in the face of their more established competitors.

I would not be without any of these three though the version by Wyn Morris is my marginal preference, as you have probably gathered. The recording conducted by Bernard Haitink on Philips boasts the Concertgebouw Orchestra and John-Shirley-Quirk at his most persuasive. Unfortunately his partner Jessye Norman fails to impress me in her awareness of words and her willingness to enter into the world of these songs. I also enjoyed the recent recording conducted by Claudio Abaddo on DG. Not least for the presence of that exciting singer of the present generation Thomas Quasthoff. Again, however, his partner Anne Sofie Von Otter fails to impress me enough and Abaddo also is just too refined when compared with Morris. Each time I hear Wyn Morris's recording I am convinced his is the one to own. Snap it up whilst it is still available but don't overlook Felix Prohaska.

There are other settings of Wunderhorn poems by Mahler but these are for voice and piano alone and can be found in recordings of all Mahler's earlier songs as "Lieder und Gesange aus der Jugendzeit". Janet Baker's splendid Hyperion recording (CDA 66100), Amazon UK in which she is accompanied by Geoffrey Parsons, is one of those small gems of the Mahler discography I recommend warmly to go into your collection. Faultless interpretations of these small jewels from the master's workshop. Some of these very early songs have also been orchestrated by, among others, Harold Byrns and Luciano Berio. Let me take this opportunity of drawing to your attention a disc featuring another great Mahlerian of the present generation, Thomas Hampson. This is on the Teldec label (Dig.9031 74002-2) and contains eleven orchestrations of early songs by Luciano Berio with the Philharmonia conducted by Berio himself. What I like about them is the fact that Berio doesn't try to think himself into Mahler's mind for songs he himself did not orchestrate. What we get is a genuine collaboration between the two men. You also get a fine version of the Wayfarer Songs thrown in. Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen Kindertotenlieder Ruckert Lieder

As you build a Mahler collection you will find recordings of these three song cycles appearing as fill-ups to some of the symphonies. I suspect this is how most collectors acquire their recordings of these works that are as crucial to understanding Mahler's art as the Wunderhorn cycle. "Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen" ("Songs of a Wayfarer") comes from early in Mahler's career and stands in relation to the First Symphony as the Wunderhorn songs do to the three that followed. The five Ruckert Lieder and the "Kindertotenlieder" ("Songs on the Death of Children"), also to words by Ruckert, come from the middle of Mahler's career and have thematic links to symphonies 5-7. It's unlikely anyone would buy a recording of one of the symphonies just to acquire a recording of a song cycle coupled with it so I'm limiting myself to discs that contain only these three song cycles on them.

Look out also for Kathleen Ferrier's account of the "Kindertotenlieder" with Bruno Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic on EMI. Amazon UK Her voice is very different from Baker's but demands to be heard. So too do Fischer-Dieskau's earlier accounts of the Wayfarer songs and "Kindertotenlieder" on EMI, the former conducted by Willhelm Furtwangler. Amazon UK

Das Lied Von Der Erde arranged for chamber orchestra

I have been amazed at the number of people who, during the course of writing these surveys, have contacted me to ask if I'm going to mention the arrangement for chamber group of "Das Lied Von Der Erde" started by Arnold Schoenberg and finished by Rainer Riehn in the 1920s. Clearly it's liked by a lot of people but I must say I fail to see the attraction for the listener today other than novelty. For performers the attractions are clearer. Here is a chance to perform a version of Mahler's masterpiece where all that is needed are a handful of players. For the singers in particular there is no need to pitch the voice against a full orchestra. However, a work that in its original form already performs miracles of chamber style writing surely needs no more transparency and hearing Mahler's wonderful textures changed like this is quite frankly painful. In a previous age this type of enterprise might have been the only opportunity an interested audience would have had to hear the work. Today, with CD recordings and broadcasts, it seems largely redundant, an echo from a previous time. However, if you're determined to give it a try and are, unlike me, prepared to stomach the sound of a piano pounding away in Mahler's masterpiece, the version conducted by Osmo Vanska on Bis (BISCD 681) Amazon UK seems the best to me with two fine singers. And finally….

Tony Duggan Later release

Gustav

MAHLER |

Return to: index

Error processing SSI file