The Third Symphony

is Mahlerís hymn to the natural world

and his longest work. It was largely

composed in the summer of 1895 after

an exhausting and troubling period that

pitched him into feverish creative activity.

Bruno Walter visited him at that time

and as Mahler met him off the ferry

Walter looked up at the spectacular

alpine vistas around him only to be

told: "No use looking up there,

thatís all been composed by me."

Mahler was inspired by the grandeur

around him at the very deepest level

of feeling and also by visions of Pan

and Dionysus. In fact by a sense of

every natural creative force in the

universe infusing him into "one

great hymn to the glory of every aspect

of creation", or, as Deryck Cooke

put it: "a concept of existence

in its totality."

To deliver a convincing

performance of the Third I believe the

conductor must do two things before

anything else. Firstly, in spite of

the fact that the work falls into Mahler's

"anthologising" strand, along with Das

Klagende Lied, the Second and Eighth

Symphonies, the overriding structural

imperative linking the six movements

must be a pattern of ascending steps

based loosely on the evolutionary ladder

within broadly-based Pantheistic cosmology.

In these terms the six movements are:

1] Inorganic nature

summoned into life by Pan, characterised

as summer after winter

2] Plant and vegetable life

3] Animal life

4] Human life represented as spiritual

darkness

5] Heavenly life represented as childish

innocence which, when combined with

5, brings

6] God expressed as, and through,

Love.

Mahlerís original titles

for these movements were:

1] "Summer Marches in"

2] "What the Meadow Flowers tell

me

3] "What the Creatures of the Forest

Tell Me"

4] "What Night Tells Me"

5] "What the Morning Bells Tell

Me"

6] "What God Tells Me"

The conductor who fails

to see this "ladder of ascent" and make

it manifest is one who makes the mistake

of concentrating too hard on getting

the first and last movements right and

neglects the movements in between, treating

them as interludes rather than steps

on the journey to perfection fashioned

out of the world around and beyond.

The first movement must also retain

a degree of independence since Mahler

designates it Part I with the remaining

movements Part II. This leads to the

second thing I believe the conductor

must do and that is render the seemingly

disparate elements of the first movement

into a rigorously-wrought whole when

the nature of its thirty-five minutes

sets it on course for structural failure.

There must be no doubt on the

part of the conductor as to the movement's

greatness and this includes an awareness

of, and an ability to bring out, the

rougher edges woven into it. Any attempt

to "prettify" or "smooth

out" the first movement leads ultimately

to a blunting of its special power and

so to failure. Itís a hard thing to

quantify but itís something you know

is there at a deep level at certain

"way points" and in the way you can

give in to its atmosphere, hallucinatory

qualities and lack of doubt in itself.

I think itís also true that a conductor's

confidence in the rightness of Mahler's

vision in the first movement stands

him in good stead for the rest. Those

conductors who get the first aspect

right tend to get the second right,

and are therefore, for me, the greatest

interpreters of this symphony.

It is very hard many

decades after a first performance to

try to gauge the effect a piece of music

first had on its early audiences. When

something has become so familiar, loved,

venerated even, to try to imagine "the

shock of the new" that must have

seized people at the time is a tall

order. But it is an idea we should try

to bear in mind if we can and so should

the performer. When Mahler wrote his

Third Symphony he was a young man wanting

to make a very big noise in the world,

to try to shake people out of complacency.

In the first movement it has always

seemed to me that Mahler was saying

to his audience, to use modern slang,

"Eat my score!" and any performance

of the piece that falls short of giving

an impression of that attitude is just

not trying hard enough. Or at least

is trying too hard to be accepted in

now more polite circles. So I think

it takes a particular kind of conductor

to turn in a great Mahler Third. No

place for the tentative or the sophisticated,

particularly in the first movement which

will dominate how the rest of the symphony

comes to sound no matter how good the

rest is. No place for apologies in that

first movement especially. The lighter

and lyrical passages will largely take

care of themselves. Itís the "dirty

end" of the music - low brass and percussion,

shrieking woodwinds, growling basses,

flatulent trombone solos - that the

conductor must really immerse himself

in. A regrettable trait of musical "political

correctness" seems to have crept into

more recent performances and recordings

and that is to be deplored. The edges

need to be sharp, the drama challenging,

Mahlerís gestalt shrieking, marching,

surging, seething and, at key moments,

hitting the proverbial fan.

Sir John Barbirolli passes this test

impressively. In March 1969 he recorded

the work under studio conditions for

the BBC and this is now available on

BBC Legends (BBCL 4004-7). No matter

what observations one might care to

make about his treatment of individual

sections, matters of phrasing, dynamics

and expression, his vision of

this work was emphatically of this journey

upwards in carefully graded steps. He

also grasped completely the first movement's

totality with no doubt as to its validity

and he wasnít ashamed of it or its rough

edges and elemental texture. The opening

on eight horns is vigorous, rude and

raucous. The recording then allows us

to hear grumbles and groans on percussion

as primeval nature bestirs, even though

the crucial uprushes on lower strings

are a little disappointing when compared

with some where they are made to really

"kick". The section that introduces

Pan himself contains a ripe delivery

of the trombone solo and when other

members of the section join in, forward

and close-miked, the effect of their

lament comes over black as doom. The

role of what passes as Exposition is

the delivery of the brassy "in your

face" march meant to signify summer's

arrival. Though with this being Mahler

he insists on hurling the workaday world

into the maelstrom. Mahler loved his

marches as much as Elgar did and this

one is his most joyous and so it comes

over under Barbirolli. The moment of

its arrival in this recording has a

particular quality which I can't imagine

any other orchestra bringing. If workers

in Vienna inspired Mahler, Barbirolli

seems to have had in mind the holiday

resorts in the north of England at the

height of summer some time in the past,

the forties or fifties, perhaps. There's

a hint of the Promenade at Blackpool:

the whiff of fish and chips, the sun

catching the silver paper on the "Kiss

Me Quick" hats, the tang of petrol from

charabancs depositing mill girls from

the looms of Manchester on Bank Holiday

Monday. Then at 347 we are dragged back

to the natural world with all its splendour

as the horns roar out the theme from

the start and the Development is underway.

I like the way Barbirolli balances his

brass sections here. It shows the value

of the orchestra having played in "live"

performances before. The important passage

at 530-642 is where Mahler develops

on the idea of marching and he

marks each section differently, something

a conductor must take note of. "The

Rabble", "The Battle Begins", "The South

Storm" are all acknowledged by Barbirolli

and this has the effect of making the

music seem to comment on itself. I was

also put in mind of some of the wilder

sections of Ives in the way the marches,

broken down into constituent moods,

seem to criss-cross each other in mesmerising

half-nightmare. There is some lovely

playing from the cellos prior to the

return of the march proper. The portamenti

the players indulge are quintessential

Barbirolli. But this is swept away because

the march has one more appearance to

make. This time I was more aware of

the long crescendo that will bring about

a conclusion to the movement. The frenzy

of the coda, starting at Figure 74,

where the orchestra explodes into wild

and crazy vistas, is well brought off.

Though not even Barbirolli can match

Horenstein here whose LSO brass are

absolutely shattering.

There is enough of

a sense of contrast between the first

and second movements to mark the change

from Part I to Part II but not too much

to deny this is the next "step" in our

ascent. There's certainly no question

of treating the movement as a lightweight

interlude and the second movement is

a lot subtler than is sometimes realised,

so the conductor must lavish the same

care on it he would everything else.

Barbirolliís walk through the flowers

in the meadows doesn't take the pretty

route. There are stinging nettles beyond

the blooms and we stumble into them

in the way the woodwind allows spiky

sounds to come through. The rhythm is

also nicely pointed when the tempo picks

up, which means when it relaxes into

lyricism the effect is that much more

nostalgic. Barbirolli next adopts a

slightly slower tempo in the third movement

but this allows a little more room to

make rhythmic points and bring out character.

I don't think I've heard the rollicking

brass descents two bars before 9 and

likewise before 23 delivered quite so

loudly and with such precision at such

volume. Barbirolli must have drilled

his players meticulously. The crucial

posthorn episode, our first glimpse

of humanity, is beautifully prepared

but the first posthorn is closer than

we are used to. However, the section

between the two appearances of the posthorn

makes up for any misgivings by being

gloriously raucous. If the posthorn

represents the first appearance of humanity

then nature has the final word with

the unforgettable passage at bars 529-556:

a crescendo from ppp to fff followed

by a diminuendo back down to pppp replete

with harp glissandi. This passage has

at its centre, a development of one

of the bird call motifs to become "The

heavy shadow of lifeless nature", rearing

up on horns and trombones. It links

back to the first movement and forward

to the end and is a key moment of crisis

that should be marked with special emphasis

so we feel threatened. Barbirolli

prided himself on being able to recognise

highlights and climaxes in each Mahler

symphony and there's no doubt he gives

this passage everything it can stand.

I would have liked a little more Stygian

gloom for the fourth movement which

is a setting of Nietzsche's "Oh Mensch"

and the first appearance of the voice.

Kerstin Meyer is a fine singer but you

can hear too much of her for her contribution

to be as mysterious as it ought to be.

I did like the way Barbirolli appears

to want us to make the connection between

her accompaniment and the start of the

first movement, though. A nice contrast

arrives with the boys and women in the

fifth movement and a return to the Wunderhorn

world heralding dawn with bells tolling.

The boys of Manchester Grammar School

are nowhere near the angelic voices

we are used to. These are urchins from

the mean streets of Manchester and give

an earthier quality to match the purer

sounds of the women and the darker,

warmer tone of Meyer. Compared with

some, Barbirolli is more expressive

and "heart-on-sleeve" in the last movement

and the big-heartedness of it all is

overwhelming. This is a true journey's

end that couldn't have been won by this

conductor in any other way. Notice Sir

Johnís expressive rubato and the singing

line of cello portamenti. His inability

to resist speeding up at moments of

release later on spoils this movement's

serenity just a little, though. But

take that away and it would not have

been a Barbirolli performance at all.

The end is built to masterly fashion

within Barbirolli's warm-hearted view.

He presses forward in the closing pages

and can't resist almost a luftpause

before the last chord of all. But he

keeps his timpani under control, just

as he should, and justifies his view

of the end as a safe harbour nobly won.

A couple of months

after Sir Johnís death the Mahler expert

Deryck Cooke declared this "one of the

finest Mahler performances I have ever

heard" and I certainly concur with

that. A sentiment confirmed by an international

jury of critics at the Mahlerwoche

in Toblach in 2000 when they gave the

recording the award for best stereo

Mahler recording of 1999. It's quite

a close-in sound especially made for

broadcast, almost a conductor's balance

with every detail clear. Some may find

the reproduction of the brass troublesome

but with good remastering it comes over

bold, brassy and exuberant like the

symphony itself and Sir John's interpretation

which more than makes up for any shortcomings

in the Halléís playing. They are some

way from the finest but you would have

to have a heart of stone and a pair

of ears to match to let occasional lapses

in ensemble and fluffed notes bother

you very much. There is poetry here,

there is drama, and there is a performance

that reflects a world of feeling now

gone.

Testament have given

an official release to a "live"

Berlin Philharmonic recording of the

Third conducted by Barbirolli from 1966.

Even though this is the Berlin Philharmonic

the standard of the playing falls below

what you would expect from that orchestra

and, as with their Mahler Second with

Barbirolli, there is just not enough

familiarity with the music for this

to challenge the Hallé version on BBC

Legends.

Another of the workís greatest interpreters

was Jascha Horenstein whose Unicorn

recording of 1970 is, for the moment,

still available (UKCD2006/7 and also

in a boxed set of symphonies by various

conductors on Brilliant 99549). The

playing of the London Symphony Orchestra

is remarkable for character, unfailing

alertness and ability to reflect every

aspect of Horensteinís view of the work.

The result of a number of "live"

performances. The introductory section

of the first movement is gutsy and elemental,

not at all a comfortable start. Just

the kind of impression Mahler must have

had in mind when he pointed Walterís

attention to the mountainous landscapes.

Notice how the first trombone solo,

heavy with funeral dread, conveys a

sense of expectancy. Notice too how

Horenstein can vary his approach straight

after to take in delicacy. Itís Horensteinís

total grasp of every aspect of the first

movement and his matchless sense of

structure that welds the movement into

an expressive whole and rivets the attention

throughout. It also allows him to mark

a real spiritual aspect in the episode

of the march in the way it approaches

from a distance before bursting on us

and coming to a climax that is, like

the opening, raw and rugged. Iíve always

believed Horenstein was aware there

is a lot more than mere programme music

here. Notice how order and chaos seem

genuinely pitched against each other

in the central section where the marches

meet. In this we can witness an aspect

Arnold Schoenberg drew attention to.

That this movement (and the symphony

as a whole) is a struggle between good

and evil. Horenstein certainly conveys

struggle here to a greater extent than

many conductors do. The close of the

movement sees the performance emerge

on the side of the angels but not before

Horenstein delivers the most breathtaking

account of the closing pages themselves.

At Fig. 74, where harp glissandi introduce

an explosion of brass, Horenstein grades

the brass dynamics from fortissimo,

through piano and then up to

triple forte, with the latter

absolutely shattering. No other conductor

on record quite matches this moment.

The crashing and pounding percussion

that follows are really abandoned also.

Magnificent.

The second movement

is, as with Barbirolli and as we will

find with Leonard Bernstein, the perfect

Prelude to Part II and distinguished

again by the playing of the LSOís woodwinds.

Horenstein also notes the darker sides

of the movement, realising these are

not just pretty blooms in the meadow

being depicted, but weeds too. In the

third movement thereís a hazy, nostalgic

feel in evidence, but when muscularity

is called for, as with the first movement,

Horenstein is not found wanting. The

posthorn solo is played on a flügelhorn

making this one of the most distinctive

accounts before us. Notice also how

Horenstein pays attention to the phrasing

of the woodwind around the solo. The

great "way point" of this

movement, the rearing up of raw nature

prior to the gallop for home, finds

Horenstein and his players really on

their toes. The "Oh Mensch"

fourth movement is dark and atmospheric

but detailed also. This is a perfect

tempo for this movement and so Norma

Proctor is given all the space she needs

to make every word clear. Clarity is

also the keynote in the fifth movement

where the boys are a joy Ė sharp and

cheeky in the way they burst in on the

silence. Though intensely beautiful

in parts, Horenstein doesnít neglect

the drama and tension implicit in the

sixth movement and doesnít stand in

the way of the great beauty and sense

of contemplation. This great Brucknerian

also brings out the qualities the movement

seems to inherit from that composer

in the musicís sense of slumberous growth.

The end emerges naturally with the final

timpani notes very prominent, a feature

of this recording, which leads me to

say the sound balance is not ideal.

It favours the winds with the lower

strings especially further back in the

picture than they should be. But this

is the only cloud on the horizon of

this classic recording. In lesser hands

this symphony can sag in parts. Never

once under Horenstein is there any sense

of that. His concentration is stunning

and every bar seems to have something

to say. This remains one of the greatest

recordings of any Mahler symphony ever

set down and I think it always will.

Over the years my high

regard in this survey for these two

recordings by Barbirolli and Horenstein

have generated more critical comment

than any of my choices across the whole

synoptic survey both in private e-mails

and in public internet forums. True,

there are more who will go along with

my estimation of the Horenstein recording,

but even I have to admit I plough quite

a lonely furrow where the Barbirolli

recording is concerned. So it goes.

I will carry on singing the praises

of both these recordings in the general

profile. I can do no other but write

what I feel and hope those interested

will listen with open ears. As I say

in my Preface, this survey is a personal

selection.

Less disagreement greets my high regard

for Leonard Bernstein in this work,

of course. Of his two studio recordings

with the New York Philharmonic I prefer

his first one on Sony (SM2K 47 576).

Itís much the same interpretation as

on the later DG release but the playing

of the NYPO in 1961 has more sense of

discovery. I also think the earlier

recording, though showing its age, is

still a better sound picture overall.

Bernstein is alive to every nuance of

the score but, as in his recording of

the Seventh from the same period, he

lets the music speak for itself right

the way through. That isnít to say his

reading doesnít have distinctive qualities,

not least in the first movement. At

the start thereís a definite feeling

of a journey beginning as the horns

roar and thereís also a sense of latent

energy. This is a feeling that will

persist and is what infuses the great

uprushes from the lower strings in the

opening pages which are projected with

superb attack from the New York players.

As too are the woodwind choirís squawks,

like birds on a wire startled into life

by some noise at dusk. Following the

great trombone solo Bernstein segues

seamlessly into the main exposition

material where the march of summer finds

him in characteristically exuberant

mood. If Barbirolliís march was Blackpool

Promenade on August Bank Holiday, Bernsteinís

is New Yorkís Fifth Avenue on St. Patrickís

Day, and none the worse for that. His

explicit sense of the march material

means his treatment of the crucial central

episode (530-640) comes off splendidly

with the tensions of "live"

performance and more than a nod towards

Charles Ives, a composer who must have

been in this of all conductorís mind.

There is tremendous frenzy whipped up

here with every subtle change of tempi

taken care of and a definite sense of

danger that seems most appropriate.

The conclusion crowns the movement with

power, grandeur and excitement combined.

I could imagine some finding Bernsteinís

exuberance in this movement just over

the top, but this music is "over

the top" to start with so Bernstein

and Mahler just about balance this time.

There is lovely attention

to detail in the second movement and

a real sense of flight in the quicker

passages. Most important of all Bernstein

realises this is a prelude to what follows

and there is no sense of relaxation,

even though the felicities of the score

make their nostalgic effect. The latter

also applies to the third movement that

finds a slightly more relaxed tempo

than some recordings. This allows the

woodwind especially to convey the charm

of the music by articulating every note

and for everyone else to get across

a real swing to the animated

passages. The rollicking brass should

bring a smile to your face if you have

ever heard more sober views. The posthorn

solo is sweet and mellow proving, as

elsewhere, that Bernstein can relax

when he needs to. Around the second

appearance of the posthorn he also gets

his strings to throw a shimmering haze

around the player which is magical.

Then when raw nature rears up at 529

the effect is even more big-boned, sexy

and dramatic than it might have been.

The fourth movementís "Oh Mensch"

brings some rapt playing and Martha

Lipton is a veiled witness. The fifth

movement with the boys and women comes

over remarkably restrained for Bernstein.

A bigger choir might have helped and

maybe this is the only movement where

I feel any great sense of disappointment.

Bernstein takes the last movement slowly

and with great dedication. However,

unlike some, he brings that kind of

tempi off because he never overloads

it with too much emotional weight. He

seems to have realised the music has

plenty of its own already in it. All

flows from within, just as it should,

and the attention is held from first

bar to last and an ultimate triumph

that is natural and solid.

Rafael Kubelikís excellent DG studio

version is currently available only

as part of his complete cycle (463 738-2)

but has always been for me on a par

with Barbirolli and Horenstein. It has

one main drawback in that the recorded

balance is, like the rest of his Munich

studio cycle, close-miked and somewhat

lacking in atmosphere. It never bothered

me that much but just occasionally I

felt the need for a little more space.

As luck would have it, since the first

version of this survey appeared, an

Audite release (23.403) in their series

of "live" Mahler performances from Kubelikís

Munich years in the archives of Bavarian

Radio has now appeared. It even comes

from the same week as the DG studio

version and must have been the concert

performance mounted to give the players

the chance to perform the work prior

to recording in the empty hall. It goes

some way to addressing the problem of

recorded balance in that there is a

degree more space and atmosphere and

also more separation across the stereo

arc. It thus offers an even more satisfying

experience whilst still delivering Kubelikís

gripping and involving interpretation

with the added tensions of "live" performance.

There is a little background tape hiss

but nothing that the true music lover

need fear. So, like with the Barbirolli,

(and the Scherchen and Martinon recordings)

dealt with below), here is yet another

"not originally made for release" broadcast

recording of Mahlerís Third for the

list of top recommendations.

Like all great Mahler

Thirds it has a fierce unity and a striking

sense of purpose across the whole six

movements, lifting it above so many

versions that miss this crucial aspect.

Tempi are faster than you may be used

to, let me stress. It also pays as much

attention to the inner movements as

it does the outer with playing of poetry,

charm and that hard-to-pin-down aspect,

wonderment. In the first movement

Kubelik echoes Schoenbergís belief that

this is a struggle between good and

evil, generating the real tension needed

to mark this. Listen to the gathering

together of all the threads for the

central storms section, for an example.

Kubelik also comes close to Barbirolliís

raucous, unforgettable "grand day out

up North" march spectacle and shares

his British colleagueís and Leonard

Bernsteinís sense of the sheer wackiness

of it all. (Why are modern day conductors

so afraid to see this aspect?) Listen

to the wonderful Bavarian basses and

cellos rocking the world with their

uprushing basses and those raw, rude

trombone solos as black as an undertakerís

hat and about as delicate as a Bronx

cheer or an East End Raspberry. Kubelik

also manages to give the impression

of the movement as a living organism,

growling and purring in passages of

repose particularly, fur bristling like

a cat in a thunderstorm. Too often you

have the feeling in this movement that

conductors cannot get over how long

it is and so they want to make it sound

big by making it last for ever. In fact

it is a superbly organised piece that

benefits from the firm hand of a conductor

prepared to "put a bit of stick about"

like Kubelik does.

In the second movement

there is a superb mixture of nostalgia

and repose with the spiky, tart aspects

of nature juxtaposing the scents and

the pastels. Only Horenstein surpasses

in the rhythmic pointing of the following

Scherzo but Kubelik comes close as his

sense of purpose seems to extend the

chain of events that was begun at the

very start, still pulling us on in one

great procession. The pressing tempi

help in this but above all there is

the innate feel for the whole picture

that only a master Mahlerian can pull

off and frequently only in "live" performance.

Marjorie Thomas is an excellent soloist

and the two choirs are everything you

would wish for. Though Barbirolliís

Manchester boys are just wonderful.

Like Barbirolli, though warm of heart,

Kubelik refuses to indulge the music

of the last movement and wins out as

the crowning climax is as satisfying

as could be wished. This is a firm recommendation

for Mahlerís Third and another gem in

Auditeís Kubelik releases.

Whilst dealing with earlier interpreters

on record, the name Charles Adler might

be unfamiliar to many people today but

he was a Mahler pioneer too who made

the first recordings of the Third and

Sixth Symphonies, as well as the Adagio

of the Tenth, for a label he financed

from his own resources. He also might

have known Gustav Mahler as heís thought

to have been one of the assistants who

helped train the choruses for the first

performance of the Eighth in Munich

in 1910. Adlerís recording of the Third

was made in Vienna in 1951 with the

Vienna Symphony Orchestra and, on first

release, boasted sleeve notes by Alma

Mahler herself. Remember that until

1960 this was the only recording of

the Third available so it helped form

the impression of this work for a generation

of Mahlerites giving it a firm place

in the history of Mahler recordings.

Itís now available on French Harmonia

Mundi (HMA 190501.02) or Tahra (Tahra

340). It is claimed that the occasional

deviations from the score an experienced

listener will notice came from Mahler

himself. If true it adds interest to

the recording over and above the considerable

virtues to be found in it. There is

spaciousness and weight to the first

movement which, when allied to the distinctive

Viennese playing style and sound still

preserved in 1951, takes us back to

another world. This can be heard especially

well in the sound of the horns and in

the aching lyricism of the contrasting

sections in the introduction. The summer

march then builds from very gentle beginnings

to emerge in grandeur. All through Adler

justifies his weightier, muscular approach

by a miracle of concentration and by

the response of his players who, whilst

never the last word in security, have

this music in their bone marrow. There

is, I believe, a hint of what this work

might have sounded like under Mahler

himself especially in the mellow horns

and in a hundred different ways in which

the strings turn a phrase. Maybe the

rougher mono recording helps but the

contrast of toughness and lyricism is

most engaging too. The close of the

movement is built up to over a huge

span and rises to a massive climax to

seal a deeply impressive account.

The second movement

stresses lyricism again with some perky

woodwinds. Again the way the strings

phrase their contributions is the kind

of playing you really donít hear today

and might sound quite unfamiliar to

younger listeners. But I believe it

tells us a lot about this work we might

otherwise miss. The third movement is

rather held back in tempo but, as with

Barbirolli and Bernstein, benefits from

this in having time to allow the myriad

details to make their effect, woodwinds

especially. There is real atmosphere

conveyed, not least in the posthorn

played by its Viennese soloist "to

the manner born". There is one

bad edit after the second posthorn where

two sessions seem to have been spliced

together with two different tempi to

match, but try not to let that bother

you. Hilde Rössl-Majdan gives a surprisingly

passionate performance of "Oh Mensch"

and, rather like Bernsteinís recording,

this leads to a much gentler account

of the fifth movement. The last movement

under Adler is then very pure and ethereal

in parts. The body of strings is not

as large as it might be and itís in

the last movement this shows most. However,

I still want you to be aware of this

recording for all that it can tell us

about Mahler performing practice. The

mono sound shows its age a little, but

a few minutes getting used to it is

all thatís needed to adjust and enjoy

a fine performance with many virtues.

Whilst on the subject

of Mahler pioneers you should be aware

of a "live" recording by Hermann

Scherchen and Leipzig radio forces from

1960. This is now available in a Tahra

release (TAH 497-498 coupled with the

Tenth Adagio) giving you a "live"

performance by that most individual

of Mahler conductors that should provide

you with a fascinating alternative view

well off the mainstream. Let me also

at this point mention in passing another

superb radio broadcast recording of

this symphony that I think demands general

release. Itís by Jean Martinon and the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra and has been

commercially available as part of a

large and expensive commemorative box.

For that reason I will not deal with

it in any detail. Suffice it to say

that I consider it the equal of the

great classic recordings for all the

reasons I have tried to set out. Surely

a label could be found who would release

it singly.

So far I have dealt

only with recordings from before 1970.

So I think I am justified in calling

them recordings from a previous era

of conductor and sound. They are certainly

analogue, all of their conductors are

now dead, but they still impress, still

seem in touch with a view of this work

that seems to have gone. When writing

the first version of this survey I was

hard pressed to then find recordings

from the more recent past and in digital

sound that I thought came anywhere near

the achievements of the versions dealt

with above. But I did have a go and

I see no reason to strike any of those

that I included out as they are fine

achievements and still worth consideration.

Giuseppe Sinopoli with the Philharmonia

Orchestra on DG (447 051) is as good

a place as any to start. The sound recording

is superb - bold and rich, with lots

of unobtrusive atmosphere. There is

also splendid playing from the start

with clear and "up-front"

lower string uprushes that have an extra

element of impetuosity about them. The

trombone solos are splendidly ripe,

and note also the cracks from the bass

drum here and right through which are

wonderfully caught. Sinopoli is aware

of every colour in Mahlerís special

sound palette as he is also of the rhythms

in the march whose tension he builds

inexorably. When the summer arrives,

Sinopoli delivers exuberance but just

stops short of Bernstein in this. Note

the superb trumpet playing prior to

the start of the development and also

in the central crisis where the marches

join battle. Here Sinopoliís structural

grasp is as sure as Horensteinís, aiding

his ability to convey the struggle for

good over evil that Schoenberg noticed.

The closing pages are a culmination

not just of the re-start of the march

but of the whole movement.

Can Sinopoli maintain

such a promising start? Indeed he can.

Delicacy is the watchword in the second

movement, especially the care shown

to the inner string parts and the way

the music is moulded, but not excessively

so. Sinopoli can frequently be heavy-handed

in Mahler but here his touch is a light

one. The same applies to the third movement

but this doesnít prevent Sinopoli from

bringing great swing to the heavier

scored parts that emerge with life-enhancing

drama. When the posthorn solo arrives,

the delicacy already noticed carries

us into a dream landscape, enhanced

by one of the best accounts of the solo

on record (John Wallace?) leading to

a genuinely awesome delivery

of the Nature arrival ushering in the

fourth movement. Under Sinopoli and

sung by Hanna Schwarz, this is suitably

crepuscular which makes the bright and

breezy fifth movement a real wakening

to the day. I feared the last movement

would be where Sinopoliís judgement

would desert him and he would spoil

everything by pulling the music around

too much. Not so. What he gives is a

noble and warm account with climaxes

that donít overwhelm, rather that seem

perfectly natural parts of the whole,

as do the final pagesí timpani contributions

which are never allowed to swamp the

texture. Sinopoliís Mahler Third is

one that should be a leading contender

for the library. Superb sound, playing

and interpretation.

Jesus Lopez-Cobos and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on Telarc (80481)

give a lively opening that brings distinctively

grainy trombone sounds like nothing

else on any other version. There are

also some great "kicks" from

the lower strings as they burst from

the depths. This is not a pretty opening,

in fact itís quite ugly. Itís one of

those in the tradition that sees this

music cut from the landscape with the

bluntest of instruments. Lopez-Cobos

then has another surprise or two in

store with a dance-like quality to the

lyrical passages that accompany the

opening and then a somewhat agitated

account of the first trombone solo with

violence lurking in the background.

Summer itself has an airy, open-air

quality and some energy to it thatís

refreshing and the very immediate recording

balance helps him in what appears to

be a much more radical, Wunderhorn view

of this work. No attempt to smooth out

the shifting moods and sounds. The March

sections are superbly done, prepared

for with some tension and delivered

with vigour and the close has all the

architectural security of Horenstein

and the colour and blaze of Barbirolli.

Notice too how Lopez-Cobos and his engineers

make you hear all the woodwind contributions.

The second movement

is fleet-footed and very precise. A

refreshing account indeed which puts

Lopez-Cobos in with those who lavish

care and attention on this short movement.

I especially like the character of the

woodwind and the transparent textures,

which are carried over to the third

movement. Here there is a lovely rhythmic

snap in the more animated passages and

a post-horn solo dreamy and distant.

In all, an account of this movement

that covers all aspects. I also felt

Lopez-Cobos had in the back of his mind

the sound of the Fourth symphony in

these two movements, reinforcing in

my mind the impression that he doesnít

lose sight of the fact that this is

a Wunderhorn period piece. Michelle

de Young is a rapt and sonorous soloist

in the fourth movement with Lopez-Cobos

in excellent support. In the fifth movement,

he shows again his ability to illuminate

elements others miss. Like the string

accompaniments, which seem to receive

special attention and some fine playing

from the Cincinnati orchestra. This

adds to a fine sense of flow that

carries over into the last movement

making the kind of culmination that

it ought to be. Lopez-Cobos is a touch

more detached in his textures than others

are here but not so much that it detracts

from his flow. Itís a fine alternative

to the more "heart-on-sleeve"

conductors since Lopez-Cobos has a lighter

touch that pays dividends in that the

optimistic side to Mahler wins out in

the end. Iíve always believed this to

be Mahlerís least troubled work and

itís good to hear Lopez-Cobos appears

to have reached that conclusion too.

The sound recording is less sumptuous

than, for example, Sinopoli. But I enjoyed

its detail and musical sense and hi-fi

fans should note this is encoded in

Telarcís "Surround Sound".

Simon Rattle's recording on EMI (56657)

with the City of Birmingham Symphony

Orchestra followed live performances

but I wish they had issued one of those.

Having heard a broadcast of one I felt

the presence of the audience gave the

players a greater sense of unfolding

drama. The sound here is rich, deep

and well upholstered. Very much a concert

hall balance with a wide spread left

and right and good front-to-back perspective.

The CBSO horns open the work with a

sense of space, both physical and musical,

with each note spaced out more deliberately

and the horns themselves sounding less

penetrating than I think they should.

Overall the brass of the CBSO are more

cultured and cushioned than the Hallé

for Barbirolli or the LSO for Horenstein,

so they offer a better blend. But there

is some loss of character. The trombone

solos are little too well mannered too,

I think. The strings are well balanced

and there appear to be enough of them

for the uprushes from lower strings

to really shudder from the depths. Rattle's

main march is well done in terms of

tempo and weight and is also very grand.

But I think it misses the greater swagger

of Bernstein and Barbirolli and the

sense of the approach from far distance.

In the passage at 530-642 where Mahler

develops on the marches Rattle could

have learned a lot from the example

of his older colleagues. Horenstein

and Bernstein never lose track of the

plot where Rattle seems to have done

at the start. He redeems himself in

the "Ivesian" frenzy but then lets the

music sag again in the long, dreamy

section before the march resumes for

the Recapitulation. With Rattle my attention

wondered whereas with Barbirolli, Horenstein

and Kubelik I remained riveted. Rattle

also seems to cushion the climaxes at

the end. The impression is that he might

want to save something in his arsenal

for later.

The second movement

gets a lovely performance. Then in the

third the opening woodwinds of the CBSO

show great character and a more cultured

and refined delivery. It's really a

question of taste as to whether you

prefer a more homespun sound like that

for Barbirolli and Horenstein. Rattle

seems anxious to luxuriate in the details

of this movement where others prefer

to be more extrovert. This does lead

to an unforgettable delivery of the

posthorn solos in the Rattle recording.

The lead up is given a deliberate slowing

down which in "live" performance

was a piece of concert hall theatre

worthy of Furtwangler and then in the

recording the player impinges into our

aural imagination from a huge distance.

In the interlude between the two passages

Rattle then coaxes his muted brass players

to cluck like an expectant hen house

- "What the animals tell me", indeed.

Rattle is more reined-back in the passage

at the end of the movement where Nature

rears up and, again in comparison with

others, disappoints. He seemed more

concerned with the beauty of sound that

can be drawn from this moment rather

than its earthy, elemental ugliness.

The backward depth in the sound stage

means that the fourth movement starts

with a considerable advantage as Birgit

Remmert emerges from way back, singing

with greater insight into the words

and character of her part than most

counterparts. The most noticeable difference

with Rattle in this movement concerns

his renowned zeal for bringing out every

detail of the score because this leads

to a controversial decision. There is

an important solo for principal oboe

and cor anglais and Mahler's instruction

to the player is "hinaufziehen".

A friend who was at one of the live

performances described the sound produced

by CBSO principal oboe Jonathan Kelly

as "an extraordinary upward glissando".

Rattle may have interpreted exactly

what Mahler asks for but hearing something

I'm so familiar with played in a way

I'm so unfamiliar with makes me wonder

if this is a detail to far. Rattle learned

the effect from an off-air recording

by Berthold Goldschmidt and the Philharmonia

Orchestra from 1960. Rattle also adds

girls to his boys choir and so there

is a difference between his fifth movement

and many others. There is more warmth

but I feel less contrast. I prefer Barbirolli's

unvarnished honesty though Rattle's

orchestral accompaniment is very telling.

Rattle is restrained in the last movement.

He finds a degree of expression a few

notches beneath Barbirolliís and Bernsteinís

and supplies more of the inner spirituality

of Horenstein which the movement benefits

from. He doesn't slow up too much, though.

He agrees the movement should have ebb

and flow, but his ebb and flow is within

narrower limits than Barbirolliís or

Bernsteinís. The string players in Birmingham

have more weight of tone and seem better

able to deliver a true pianissimo and

more levels of dynamic than their Manchester

counterparts who were, perhaps, given

a separate agenda. At the close Rattle

is very satisfying. If you are looking

for a modern version of Mahler's Third,

superbly recorded and played, with a

care for detail that takes you deep

into the complexities of this remarkable

work, Rattle is a contender though not

a leading one.

Klaus Tennstedtís version was mentioned

in passing in the first version of this

survey and I realise now this was a

mistake and one I am pleased to correct.

He always seemed to approach Mahlerís

music from its past rather than its

future. Under him the symphonies emerge

as works by a composer standing at the

culmination of a 19th century tradition

of romantic symphonies rather than at

the start of its disintegration in the

20th. Sonorities are often richly and

grandly presented, romantic and expressive

opportunities are likely to be grasped

with alacrity, astringency and harshness

tends to be underplayed and tempi are

frequently, though not always, expansively

presented. Tennstedt still has a legion

of admirers for whom he can seemingly

do no wrong and though Iíve never counted

myself among them I have always admired

his Third in spite of reservations relating

to those characteristics I have outlined.

(EMI 5 74296 2 coupled with the Fourth

Symphony.) One of the aspects of Tennstedtís

Mahler conducting that always concerns

me most is that he seemed surer of himself

when the music was dark and tragic.

That he often appeared unable, or unwilling,

to deliver as convincingly as others

did those passages when Mahler lightens

his mood and tone. It seemed that Tennstedt

was "marking time" in those

passages until the next chunk of tragedy

or drama came along. Perhaps we could

say that when Tennstedt turned to Mahler

there was "something of the night"

about him. But if a performance of Mahlerís

music is going to do it justice it must

bring out every aspect in equal measure.

Only then are the full implications

of Mahlerís unique qualities, his world-embracing

visions, likely to emerge best and most

especially in movements where he changes

frequently from one extreme to the other.

I never really felt Tennstedt really

did that. The first movement of the

Third is one such movement, perhaps

a paradigm, and is therefore a "graveyard"

for conductors who cannot bring this

aspect off. The opening paragraphs see

him as a Sisyphus pushing his rock with

the accent on weight and drag. Few versions

are as doom-laden as this and it is

certainly a memorable account of this

part of the score. The problem is that

when the lighter music arrives, with

woodwinds chirruping and squawking in

the dovecotes and strings lifting the

music aloft as if those birds have flown,

the mood seems to remain dark whereas

it should change profoundly to signal

the pattern for the rest of the movement.

The great trombone solo is also surprisingly

tame where it really ought to be rude

and raucous. Itís as though Tennstedt

wants to keep this as a creature of

the dark also. Likewise in the build

up to the march crisis in the development

there is the sense of Tennstedt waiting

for the moment when he can unleash his

forces in mass attack which he does

do with great effect. So I think he

again misses the musical equivalent

of montage film editing that gives equal

attention to every passage rather than

some. There are impressive things in

this movement, though. The sound of

the LPO horns roaring at the climax

of the expositionís march of summer,

for example, and the close of the whole

movement with brass and percussion sweeping

all before them. But Horenstein, Barbirolli,

Kubelik and Bernstein all have a better

grasp of every feature of this movement.

The rest of the symphony

under Tennstedt works much better, though

it cannot be said too often that an

account of the Third where the first

movement doesnít convince is a Third

with one hand tied behind itís back.

It might well be because each of the

following five movements essentially

has just one mood which Tennstedt can

therefore stick to. Just to prove he

is capable of the light touch the second

movement is warm and beautifully pointed

with a carefree air. The playing and

recorded balance is alive to every colour

and this carries over to the third movement

where a nice feeling of urgency also

gets injected into the system. The two

posthorn solos are superbly atmospheric

and notice the violins in the passage

between them and the splendid woodwind

squeaks just prior to the second entry.

It should go without saying Tennstedt

manages the great rearing up of natureís

power at the close of the movement with

awesome effect. The fourth movement

finds Ortrun Wenkel a more open and

expressive soloist than we are used

to though I would have liked, once again,

more contrast for the entry of the boys

in the fifth movement. However, the

real surprise and pleasure comes in

the last movement where Tennstedt confounds

expectations to deliver one of the best

accounts I have heard. Too many conductors

take the arrival of this movement as

the signal to slow down, even seeming

to try to outdo each other as to how

slow they can take this music, some

stringing it out into glacial progress.

But this music is an anthem not a wake

and Tennstedt keeps things moving forward

so that the underlying tension is never

allowed to flag and neither is the attention

of the listener. Iíve heard accounts

of this music where I have frankly become

bored by it. By keeping his eye firmly

on the closing pages and when these

arrive delivering them without overheating

the emotion, Tennstedt brings the work

home on a really triumphant note. Not

at all like Klaus Tennstedt, in fact.

These were the most

outstanding of the modern versions that

I included in the first version of this

survey. The intervening years since

have been very good to this symphony

and whilst I still think Sinopoli and

Lopez-Cobos in particular still deserve

their leading places there are now other

newer recordings that are as fine and,

in three cases, even finer. The question

at the top of my mind this time around

in this survey is whether any of these

could now challenge the old guard, give

me the Holy Grail of a modern digital

recording by a conductor of our own

time worthy to be listed in the same

breath, something I failed to find last

time. I will tell you now that whilst

some new recordings come very close

there is one, at last, that I think

does meet that formidable criteria,

but more of that one later. Let me first

deal with two new recordings that I

think donít quite make the grade but

are included here because they are borderline

and they illustrate better the virtues

of the ones that do.

Above I wrote that I think it takes

a particular breed of conductor to turn

in a great Mahler Third. No place for

the tentative and no place for the sophisticated.

The greatest interpreters have all knocked

about the world and been knocked about

by it. Andrew Litton with the Dallas

Symphony (Delos DE3248) gives every

impression of not falling into this

category as what he gives us is an all

too sophisticated, contrived and ultimately

complacent reading that makes me wonder

if he really believes in Mahlerís vision

or whether he isnít, in effect, rather

embarrassed by it all. Attention never

flags in the immense first movement

but neither is there what you could

call an attitude. Which means

the performance is not marked out for

distinction from those who have gone

before. Rather that Litton appears daunted

by the forces Mahlerís imagination unleashes

and he has decided the best thing to

do is get out unscathed, which he does

and with much aplomb. But is "aplomb"

appropriate in this movement? A crucial

passage is between bars 530 and 642

where the March that dominates the animated

sections does battle with the primeval

forces to see who is dominant. It should

be the scene of abandon, danger and

struggle. Under Litton itís just an

example of fine orchestral playing and

sound recording where the level of attack

seems blunted. So often in other passages

there is the feeling Litton cannot bear

to let things get too much out of control.

The usually awesome climax at 367-368,

where the enhanced horn section is left

bellowing at the universe, Litton again

hangs fire. The second movement has

elegance and charm and seems to suit

Littonís style more. Mahler wrote about

the third movement: "This piece

really sounds as if all nature were

making faces and sticking out its tongue.

But there is such horrible, panic-like

humour in it that one is overcome with

horror rather than with laughter."

A tall order for the conductor which

only the best come close to matching.

Littonís animals all sound too Beatrix

Potter to me. The lovely Posthorn solo

is well brought off, but even here I

thought Litton and his player go for

the saccharine bringing us music more

suited to a candy advert. Then in the

passages between the two solos we are

faced again with that problem we faced

in the first movement. There is no sense

of the dangerous abandon for it to bring

us close to Mahlerís "horrible,

panic-like humour." There is also

that crippling habit Litton has of holding

back when he should let rip which shows

itself especially in the amazing passage

from 529-556, a crescendo from ppp

to fff followed by a diminuendo

down to pppp that Mahler describes

as "the heavy shadow of lifeless

nature". Nathalie Stutzman has

a full and verdant tone and fine sense

of words in the fourth movement but

the problem is Litton pushes her and

the orchestra along too much. The reading

of the great last movement that Litton

then gives is sweet and intense to start

with. It is possible for the attention

to be allowed to wonder unless the conductor

has a clear idea of where is has come

from, where he is now, and where heís

going. The only aspect Iím aware of

with Litton is a desire to beguile the

ear. The orchestra plays well but doesnít,

as yet, have the ability to convey the

idea they are reaching back into a real

tradition of playing this music.

After listening a number of times to

the version by Benjamin Zander (Telarc

3SACD-60599) I made the "mistake" of

listening again to the recording by

Hermann Scherchen and also the unreleased

one by Berthold Goldschmidt already

mentioned, both from 1960. Straightway

I knew what I had been missing. These

two great Mahler interpreters of the

past may not be blessed with the kind

of rich and detailed digital sound that

Zander is given but such is their uncanny

and innate understanding of the deep

structures of this work that matters

of sonics cease to matter. In Scherchenís

case he is even labouring under the

disadvantage of conducting an orchestra

that would struggle to be called second

rate. No matter. Such is the playersí

grasp of what Scherchen is doing that

even their technical shortcomings cease

to matter all that much. In the case

of Goldschmidt he had before him what

was then one of the worldís best orchestras

- in fact the same one as Zander, albeit

of forty-three years ago. I must say

that on this evidence the Philharmonia

of 1960 knew their Mahler more intimately

than their counterparts of 2003. Surprising

because in 1960 they had never played

the work before yet still had it within

them to bend their collective spirit

in a manner of playing, a tone of musical

voice, that now seems lost. Both the

older conductors project a symphony

full of ambiguity, cocky self-confidence,

naïve poetry, warmth of heart,

wonderment and an emotional richness

that comes not from an outside-in imposition

but percolates out from the core, all

in overarching, urgent, forward-moving

structures that have you on the edge

of your seat from first note to last.

Just like my preferred stereo versions

from pre-1970, in fact. It is a Mahlerian

truth that a performance of the Third

that fails to bring off the first movement

successfully and idiomatically is fatally

wounded. That is the case with the Zander

recording. The horn-led opening under

him is powerful, leonine and vividly

projected, but not nearly elementally

seismic enough. The high woodwind

trills which become scattered right

through the movement seem far too regimented

and cleanly delivered to approach the

demented squawks Mahler surely intended.

The trombone solos are well played but,

as with the woodwind trills, are still

too contained, not rude enough. All

of this is symptomatic for me of Zander

not really "getting" this symphony.

Under Zander there seems in the whole,

long introductory passage of the first

movement too literal a presentation

of the material, a feeling the desire

is to present the notes rather than

what lies beneath them. The great march

of Summer sees the bands beautifully

turned out and well-drilled, though

there is in the recorded sound an edge

to the brass when playing full out that

is tiring on the ear. Following the

horn sectionís crowning of the climax

at the mid point of the movement the

lead-back to the return of the march

and the stormy variation of it leaves

me with the impression that Zander didnít

really know what to do with this transitional

passage. That heís just longing for

that storm to come up. The battle of

the storms is not as bone-shaking as

it could be. Itís a stiff breeze rather

than a hurricane. The coda, capable

of being the most exciting music that

Mahler ever wrote, is ruined. Zander

presses so hard down on the accelerator

I was put in mind of the way Furtwängler

used to conduct the coda to the last

movement of Beethovenís Ninth. The orchestra

just about hangs on, but all nature-storming

grandeur is knocked down in the rush.

The second movement

does contain some nice touches, in the

string playing especially, but the slides

are strictly controlled, the phrasing

calculated. The third movement fares

better with more of what has been missing

in warmth and involvement, though there

is still an impression of the metrical.

Every rhythmic jump and jerk superbly

prepared and executed. But are the animals

in the forest really like that? Then

there is the post-horn solo. This wonderful

effect in the third movement is one

of Mahlerís greatest master-strokes.

In this recording Zander calls for his

soloist to use a genuine post-horn and

the instrument is even described for

us in the notes. The problem is that

the player is set so far in the distance

that you can barely hear what he is

playing. You can, of course, turn up

the volume control but you would then

have to turn it down again quickly when

the whole orchestra joins in. In the

two choral movements it was a pleasure

to hear the warm tones of Lilli Paasikivi

and the vitality of the Tiffin boys

who all lead into a consoling and grand

final movement where, at last, there

is a glimpse of what a great Mahler

Third really can be. The Philharmonia

Orchestra plays well throughout and

the recorded sound is rich, though the

dynamic range is huge as I indicated

when discussing the post-horn. Fix a

volume setting to contain the all-out

passages with comfort and you lose detail

in the quiet passages.

The newer recordings that now follow

do, I believe, challenge the older ones

more closely than the above two. Michael

Tilson Thomasís first version with the

LSO on Sony boasted the best contralto

of all in Janet Baker and a wonderful

coupling of Baker singing the Kindertotenlieder.

The Third recording had virtues but

without quite convincing me it deserved

promotion to front rank. However, Tilson

Thomas has now re-recorded the Third

as part of his ongoing San Francisco

cycle (SFSO/Avie 821936-0003-2) and

this one is a definite improvement.

Make no mistake, this is a well-played,

well-recorded, enjoyable and involving

performance. It is only when it is compared

with the older recordings that you start

to hear what is missing. If you must

have a supplement in the very latest

recorded sound then you might consider

Michael Tilson Thomasís new version,

but read on. There is in the first movement

still not quite enough of the rough-edged,

rude banality Iím sure Mahler meant

us to hear which must have so shocked

his first audience. This shortcoming

is all the more sharply felt when contrasted

with the nature painting Mahler provides

to go with it. Cases in point are the

great trombone solos. In the older recordings

mentioned above these come over almost

as a force of nature stressing bloated

fecundity. Tilson Thomasís soloist is

a fine musician but his relatively backward

placing in the sound picture and his

straight-faced delivery of this rude,

cheeky music is not powerful or coarse

enough. Under Kubelik an unforgettable

raw assault bears down on you like the

earth being ripped apart. Horenstein

and Barbirolli also pull this effect

off. This is a small aspect, you may

say. However I think it indicative of

the overall tone of the first movement

under Tilson Thomas which, by a crucial

gnatís whisker, fails to convey the

"life or death" struggle Schoenberg

noticed. Maybe itís the space Tilson

Thomas gives the music in the first

movement that makes it fall short on

the urgency aspect. Just over thirty-six

minutes is long even for this movement.

I can admire the grandeur, though. Taken

with his care for the lyric aspects

it certainly engages right the way through.

There are some carefully prepared string

tremolandi in the introduction,

and the woodwinds squawk tunefully on

cue every time their dovecotes are disturbed.

I always think Mahlerís birds should

be more Alfred Hitchcock than Percy

Edwards. This is certainly the case

from Kubelik, Barbirolli and Horenstein

and all the better to round out the

picture. The great march of Summer which

crosses and re-crosses the movement

is done with gusto and panache, as you

would expect from this conductor, though

I found his tendency to over-control

detracted from the "in your faceness"

Mahler surely wanted. This march should

just let rip and be its rude self no

matter how coarse it might get. All

of this remains the impression to the

end of the movement: grandeur contrasted

with lyricism, urgency and edge are

downplayed by too much control. From

Kubelik thereís terrific forward momentum,

even in the repose passages, and no

lack of the uglier, coarser aspects

of nature to go with the lyric ones.

From Tilson Thomas there are a few of

the colours missing, the primary ones,

and not enough sense of danger.

Tilson Thomasís control

of the second movement is strong too,

which gives it an admirably taut quality

but then detracts from the sense of

intermezzo that perhaps it should have.

There are some impressive things from

the orchestra here, though. The third

movement emerges naturally from the

second and is most enjoyable. The post-horn

solo is a little lacking in character,

both in sound and delivery. Beautifully

played but no real attempt to "sound-paint"

a mood. The great coda to the movement,

where nature rears up to bite our heads

off, is delivered splendidly with tremendous

portent and fear. Full marks to the

horn section for the lungpower. Michelle

de Young sings the fourth movement with

a matronly operatic vibrato I didnít

take to at all. Something more disembodied

is called for here. Whilst the boys

in the fifth movement are pure and bell-like

to suit the words but I miss the Manchester

lads from Barbirolli or the Wandsworth

boys from Horenstein for their sheer

cheeky edges. One of the many appeals

of Mahlerís music is how close it takes

itself to edges without quite falling

over them. This puts conductors on their

honour to save Mahler from himself when

they can. The Andante to the Sixth always

seems to me a step short of kitsch.

Likewise the last movement of the Third

seems to me a step short of mawkish

if not handled correctly. Like the slow

movement from Brucknerís Eighth this

is, for most of the time, a meditation

not a confession. I think Tilson Thomasís

"heart on sleeve" is too close to his

cuff so the music palls rather. Iím

well aware that many of you will love

it and will swoon at this kind of treatment.

I wish you well with it. For me something

a little more detached goes a longer

way, saves Mahler from himself, prevents

his music being turned into our own

personal psychiatristís couch. At the

start of the music part of me thought

I was listening to the opening of Barberís

Adagio and that canít be right

at all. Go back to Kubelik for the right

balance of "heart on sleeve" and cerebral

repose and you will see what I mean.

But thatís not the whole story of this

movement, of course. The end should

be triumphant and under Tilson Thomas

it really is just that. The heart is

warmed by the journeyís end and this

goes some way to making up for any reservations

I may have over the rest. Iím happy

to stress pros rather than its cons

here. The San Francisco Orchestra is

on fine form and they are recorded with

depth and spread in a realistic sound

picture that packs a punch when needed

but can pare down to intimacy too. It

must be said that they donít have the

last few ounces of tone colour variation

that mark out the greatest Mahler orchestras

from the others, woodwind especially.

Their brass section too is rather soulless,

especially when playing all out.

Michael Gielen has been recording Mahler

Symphonies for a number of years with

his Baden-Baden orchestra and the results

have been rightly admired. He approaches

Mahler essentially from a 20th

century viewpoint, seeing him as a composer

looking forward rather than backward.

In that aspect we hear Mahler in the

clear light of day, instrumental lines

clear, the sharp edges in his sound

palette thrown into relief, the romantic

and emotional effects not so much played

down as left to their own devices. Some

may find this last characteristic disappointing:

a barrier between them and music that

they think should move and thrill them

more. But when so many conductors seem

happy to connive with those who wish

to use Mahler as their own personal

consulting room I believe Gielen, like

his predecessor at Baden-Baden Hans

Rosbaud, presents an important and refreshing

point of view and would urge you to

try it (Hänssler Classics CD 93.017).

One of the most notable aspects

of the long first movement of the Third

under Gielen is his deliberate tempo

for the march that dominates it, crossing

and re-crossing like armies over a familiar

battlefield. There can be few recordings

where this is given with such swagger

and emphasis as here and I liked it

very much. I also liked the fact that

Gielen encourages his trombones to really

observe the written glissandi at the

start that others seem to almost wilfully

ignore. These are the kind of touches

you would expect from Gielen: examples

of his gimlet eye for radical detail

that also means he is never dull, always

with something to say. The recording

balance helps too and I was especially

impressed by how much you can hear of

Mahlerís dense textures. The many string

tremolos shimmering and the woodwinds

squealing and squawking above the heaviest

scored of passages are examples of this.

The attention to the kaleidoscopic textures

is shown at its best in the section

of the development where Mahler pitches

the March material into furious battle.

Gielen keeps track of every line of

the score for us. Not for him any attempts

to smooth out the music into more palatable

form.

The second movement

shows a nice contrast between the pastoral

minuet material and the more energetic

trios. Again notice the snaps from the

strings and the squeaks from the woodwinds.

The third movement then seems to grow

directly out of the second with some

perky, cheeky woodwinds at the start

but a very pure and ethereal trumpet

solo in the remarkable central sections.

Not for Gielen a flügelhorn here, as

in Horensteinís recording, for example.

Perhaps that would present a little

too much charged nostalgia. However

Gielen manages plenty of power in the

extraordinary passage at the end of

the movement where Mahler depicts nature

rearing up like a great prehistoric

monster. In the fourth movement the

contralto Corneila Kallisch is placed

forward and sings well but the most

notable sound you will take away from

this movement is that of the oboe. Gielen

instructs his soloist to observe Mahlerís

marking "hinaufziehen" and perform

upward glissandi, as with Goldschmidt

and Rattle, though in Gielenís recording

this effect is a little less obtrusive

and I could be persuaded to accept it

as played here. The mood of the fourth

movement should then be broken sharply

by the entry of the boys intoning the

"Bimm-Bamms" of the bells

in the fifth movement but in this recording

they really donít do that, appearing

to be set too far back to make much

impact. I also think the boys sing too

politely and sweetly even in a recording

where we are kept at greater distance.

I longed for Horensteinís urchins at

this point in an object lesson in how

this movement should sound. After this

the last movement is played with great

restraint. A restraint many will find

runs dangerously close to a detachment

for music that has so much heartfelt

emotion at its core and can stand some

coaxing even in an interpretation like

this. Certainly Gielen misses the inner

spirituality others bring. But that

is not the effect Gielen is aiming for

overall and we must accept that or ignore

his recording completely. The playing

of the orchestra remains true and committed

to the end rounding off what is still

a fine and interesting performance.

This is a worthwhile and challenging

recording of Mahlerís longest work,

fresh and clear. Not a first choice,

but certainly one to compliment versions

offering more personal involvement by

the conductor and I believe it to be

worth your consideration.

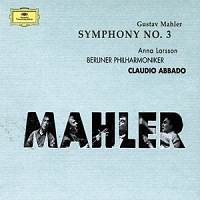

Claudio Abbado has now recorded the

Third Symphony for DG for a second time

(471 502-2). His first version was studio

made in Vienna and notable for its grasp

of detail, even though I always felt

there was something crucially missing

in the direct communication department.

Something that a "live" performance

has every chance of redressing alongside

offering a more mature interpretation.

This new performance was given by Abbado

and the Berlin Philharmonic in London

in October 1999. It was first broadcast

by BBC Radio 3 and DG acknowledges the

BBC in the liner credits so this could

be said to be a harking back to the

type of performance not meant for release

that I praised earlier. The audience

is impeccably behaved and the orchestra

on top form. Perhaps they tire a little

towards the end of the long evening,

but that is what happens in concerts