Tony Duggan passed away in 2012. Ralph Moore has

completed a survey of Das lied covering recordings Tony was never

able to hear. See

Ralph's review here.

Death was no stranger to Mahler. In childhood it visited his home and took

away brothers and sisters. In adult life he faced it down by pinning it all

over his creative work in the form of funeral marches, settings of songs

about more children dying, of drummer boys going to battlefields, of soldiers

facing execution. Death was personal. It drank in the taverns, it stared

back in the reflections of mountain streams, it glowered from the trees in

the forests. Nearer the end of his own short life, however, death lost its

sting and the composition of "Das Lied Von der Erde" ("The Song of The Earth")

could be looked on as the drawing of that sting.

In the Autumn of 1907, following the death of his elder daughter, Mahler

learned he had a heart condition. Whilst this diagnosis was not, as if so

often mistakenly believed, a sentence of death it certainly had the effect

of focusing his mind anew on mortality and mutability. It also coincided

with his being given a collection of poems which were free translations by

Hans Bethge of original Chinese verses. These seemed to magically chime in

with Mahler's growing belief about what comes after death and he selected

seven of the poems, rewriting some passages, to arrange them into six extended

song movements that form a continuous theme and variations on the leave taking

of life, "The Song of The Earth". Every mood from cynical and drunken hedonism

to serene and Zen-like stasis gets covered in the course of the hour this

work takes. At the end, the message is that, since the beauties and mysteries

of the earth renew themselves year after year, our own passing should not

be feared but accepted calmly and without rancour. The earth, the world and

nature goes on without us.

The work is a symphony in all but name and form. A completely novel creation:

a "song-symphony". This fact proved useful since Mahler shied away from calling

it his "Ninth Symphony". Composers died after their Ninths. Composition extended

over 1908 and 1909, but the first performance didn't take place until six

months after Mahler's death in 1911 when it was conducted by Bruno Walter.

A large orchestra is called for yet Mahler's use of it is like that of a

huge chamber group with many long, concertante-like solo passages and textures

often pared down to a handful of solos supporting the singer. The first

movement/song illustrates energy, hedonism and terror in the face of life,

all seen by a drunkard trying to get along by deadening his pain through

oblivion. The second is a quiet meditation on Autumn as metaphor for the

loneliness of the individual in the face of life and its inevitable end.

The third, fourth and fifth lighten the mood with descriptions of carefree

days, sunlit uplands, and more drink, hints too from the Chinese scenes at

the base of these poem unmistakably filtered through the darker-tinted glass

of turn-of-the-century Viennese angst. The sixth is one of the greatest pieces

of music Mahler ever wrote: a thirty minute meditation on leave-taking with,

at its core, a funeral march and, at its end, a long passage in which the

soloist gives us comfort that "everywhere the lovely earth blossoms forth

in spring and grows green again....for ever, for ever, for ever."

This work is perhaps the most special to lover's of Mahler's music and opinions

on performances and recordings of it are among the most disputed. With other

Mahler symphonies it's the conductor's interpretation that is principally

on trial in a survey such as this. In "Das Lied Von Der Erde", however, the

conductor's contribution must be considered on an equal footing with that

of the two singers. One weak link in this trio can flaw a recording irrevocably.

Kurt Sanderling's recording is with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra,

Peter Schreier and Birgit Finnila on Berlin Classics (0094022BC). The opening

of the first song, "Der Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde", ("Drinking Song of

Earth's Sorrow") is huge and commanding with a real weight of tone that pitches

us into the hurly-burly just as it should. Peter Schreier handles both the

louder, animated, more vigorous passages and then the softer, more lyrical

ones with equal flair and aplomb. So this is a very complete rendition of

the opening song. We know Schreier to be an artist of rare intelligence and

he shows this in spades. There is never a moment when he hasn't something

interesting to say about this work. True, he may not have a Heldentenor's

power but he makes up for this in dramatic point. For example, each repetition

of the line "Dunkel ist das leben, ist der Tod" ("Dark is life; dark is death")

that punctuates this movement as a bitter-sweet refrain, as if casting a

sidelong glance at popular song, finds a different tone from him each time,

the second an especially dying fall: a world of regret conveyed in one phrase

showing how alive he is to each nuance. In the passage beginning "Das firmament

blaut ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") I love the special treatment Sanderling

gives to the trumpets, representative of his care for instrumental detail

and an example of the support he gives Schreier's intelligent delivery. But

the passage that's the greatest test for the singer is that which describes

a nightmare vision of an ape crouching on graves in the moonlight. This is

wonderfully dramatised by Schreier without tumbling into melodrama. Notice

how he spits out the words "wild-gespenstische Gestalt" ("wild and ghostly

form"). There is a great sense of a climax reached and then a satisfying

return to lyricism for the close. This is all recognition that here is a

poem of extremes and that those extremes need to be mapped and framed by

the soloist and conductor which they are here in a deeply satisfying whole,

frightening and soothing all at once. A better start to this work could not

be imagined.

Kurt Sanderling's recording is with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra,

Peter Schreier and Birgit Finnila on Berlin Classics (0094022BC). The opening

of the first song, "Der Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde", ("Drinking Song of

Earth's Sorrow") is huge and commanding with a real weight of tone that pitches

us into the hurly-burly just as it should. Peter Schreier handles both the

louder, animated, more vigorous passages and then the softer, more lyrical

ones with equal flair and aplomb. So this is a very complete rendition of

the opening song. We know Schreier to be an artist of rare intelligence and

he shows this in spades. There is never a moment when he hasn't something

interesting to say about this work. True, he may not have a Heldentenor's

power but he makes up for this in dramatic point. For example, each repetition

of the line "Dunkel ist das leben, ist der Tod" ("Dark is life; dark is death")

that punctuates this movement as a bitter-sweet refrain, as if casting a

sidelong glance at popular song, finds a different tone from him each time,

the second an especially dying fall: a world of regret conveyed in one phrase

showing how alive he is to each nuance. In the passage beginning "Das firmament

blaut ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") I love the special treatment Sanderling

gives to the trumpets, representative of his care for instrumental detail

and an example of the support he gives Schreier's intelligent delivery. But

the passage that's the greatest test for the singer is that which describes

a nightmare vision of an ape crouching on graves in the moonlight. This is

wonderfully dramatised by Schreier without tumbling into melodrama. Notice

how he spits out the words "wild-gespenstische Gestalt" ("wild and ghostly

form"). There is a great sense of a climax reached and then a satisfying

return to lyricism for the close. This is all recognition that here is a

poem of extremes and that those extremes need to be mapped and framed by

the soloist and conductor which they are here in a deeply satisfying whole,

frightening and soothing all at once. A better start to this work could not

be imagined.

The contrast between the extremes of vigorous exuberance and heartfelt lyricism

that mark the first song and the stark, Autumnal and static feel of the second,

"Der Einsame im Herbst" ("Autumn Loneliness"), is superbly achieved by Sanderling

with an opening on strings and oboe that achieves the trick of being glacial

yet also invested with deep meaning. The delicate colours of autumn are painted

superbly as the music progresses. Finnila's entrance is arrestingly ripe

and whilst you can't say she's Schreier's equal in the rarest expression

of intelligence and drama, she does acquit herself well. Sanderling keeps

up the tempo and, in the end, manages to make this quite a passionate performance

without seeming to mould very much. There is pent-up passion held back here.

Finnila does have a lighter voice than some we are used to but I found her

very refreshing. Her grasp of the words is impressive and she responds perfectly

to the restless accompaniment by Sanderling of the one real passage of warmth

and feeling at the line "Sonne der liebe willst du nie mehr scheinen" ("Sun

of love, will you never shine again,").

Peter Schreier is the real gem of this recording with Sanderling. His delivery

of every word and phrase in the third song, "Von Der Jugend" ("Youth"), is

a joy, as also is Sanderling's accompaniment and that of his orchestra. The

lightening of tone after the previous two movements is remarkable, but even

then conductor and soloist notice that the penultimate stanza does have more

of a reflective feel to it. Schreier may not be to everybody's taste but

I love the slightly ironic stance he seems to take. There is always a cynicism

lurking behind his voice giving even the lyrical sections an edge. He seems

to want to convey the idea that, though he is the very much participant in

what he describes, he nevertheless retains his independence of mind and spirit,

like an actor's view of a great part he is enacting on stage - a Loge rather

than a Siegfried. In the fifth song "Der Trunkene im Fruhling" ("The Drunkard

in Spring") note the wonder invested into the line "mir ist als wie im Traum"

("it seems to me like a dream") and in "Der lenz ist da" ("Yes ! Spring is

here") the slight slowing down to wonderful effect. You also know he is listening

to the birds in this song and what a tuneful piccolo the orchestra supplies.

At "Ich fulle mir den Becher neu" (I fill my glass anew") there is a final

change of timbre to tell you the singer is hitting the bottle again and he

even sounds drunk in the last stanza with the final words barked out.

Finnila copes better than many with Mahler's impossible demands during the

episode in the fourth song, "Von der Schoenheit" ("Beauty"), that describes

young men on horseback surprising girls bathing by a river. The speed at

which she must take this torrent of words must fill all singers who approach

it with dread and some of the best have been known to almost come to grief.

But Finnila navigates with style. Then she manages an epilogue with all the

time and space it needs where, as so often, Sanderling is there like a rock.

However, the really big test for her is the last song, "Der Abschied"

("Farewell"), that is the centrepiece of the work.

Finnila darkens her tone for the opening and Sanderling supports her by making

sure everything can be heard in the orchestra. Remember the orchestration

for this work is one of the many remarkable aspects of it and the recorded

sound here presents a rich canvas with enough air around the instruments

and a nice bloom overall. There is also in Sanderling's gentle pressing tempo

a forward motion and great yearning. The wonderful bloom on the playing in

the passage about the moon floating like a silver ship on the blue sea of

the heavens is really made to float up and down with Finnila's singing

illustrating the words. There is similar rapport between conductor and soloist

at "Alle Sehnsucht will nun traumen," ("All longing now has turned to dreaming").

The orchestral interlude, a funeral march, is given great lyrical portent

by Sanderling and a modernist feel reminding us this is late-period Mahler.

Then note the low tam-tam at Finnila's description of the stranger dismounting

in the final section. The line "Du mein freund, mir war auf dieser Welt das

Gluck nicht hold !" ("Oh my friend fortune was not kind to me in this world")

is, I think, one of the central statements of this work and Finnila's delivery

of it is made more remarkable by the balance of her voice against the orchestra

where all details can be heard clearly, woodwinds especially. As I have implied,

she is not quite Schreier's equal in artistry, her contribution not quite

as distinctive. But we are comparing excellence so don't underestimate Finnila's

contribution which is never less than beautifully sung and phrased with each

word counting. Both Finnila and Sanderling see the end of the work as a scene

of joy and repose, regret for the loss of earthly senses, not despair, which

many commentaries on this work might imply. The whole approach in this movement

accords with so much of what Sanderling seems to be aiming for in the whole:

let the music speak, let the soloists deliver any extra expressive points

and concentrate on detail, tone and a singing line. Maybe the heart is not

wrung as in some recordings but this is as valid a view as any and I found

it deeply impressive. I also admire the recording balance which places the

singers a little further back than is often the case so the orchestra becomes

like another soloist. Since they play superbly this adds another dimension

to a remarkable and distinctive recording.

Less remarkable but no less distinctive is Eugene Ormandy's recording

with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Richard Lewis and Lili Chookasian on Sony

(SBK 53 518). This recording sells at bargain price and so must be the main

recommendation for those on the most limited resources - more so than the

recording on Naxos conducted by Michael Halasz. Richard Lewis has less attack

than Schreier in the first song. He is more mellow and lyrical and Ormandy

matches him in being more lighter-toned than Sanderling, more concerned with

the singing line and communicating energy and lift. There is less contrast

between the varying sections of the song too. The passage starting with "Das

firmament blaut ewig" is delivered by Lewis with none of Schreier's special

irony and in the ape and graves section Lewis is a little overwhelmed by

the orchestra, well as he sings, where Schreier manages to ride the climax

admirably. Not surprisingly, Lewis doesn't have Schreier's distinctive delivery

on each "dark is life; dark is death" refrain". The playing of the orchestra

is superb, though, giving notice from the start we are in the presence of

one of the world's great ensembles.

Less remarkable but no less distinctive is Eugene Ormandy's recording

with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Richard Lewis and Lili Chookasian on Sony

(SBK 53 518). This recording sells at bargain price and so must be the main

recommendation for those on the most limited resources - more so than the

recording on Naxos conducted by Michael Halasz. Richard Lewis has less attack

than Schreier in the first song. He is more mellow and lyrical and Ormandy

matches him in being more lighter-toned than Sanderling, more concerned with

the singing line and communicating energy and lift. There is less contrast

between the varying sections of the song too. The passage starting with "Das

firmament blaut ewig" is delivered by Lewis with none of Schreier's special

irony and in the ape and graves section Lewis is a little overwhelmed by

the orchestra, well as he sings, where Schreier manages to ride the climax

admirably. Not surprisingly, Lewis doesn't have Schreier's distinctive delivery

on each "dark is life; dark is death" refrain". The playing of the orchestra

is superb, though, giving notice from the start we are in the presence of

one of the world's great ensembles.

Ormandy opens the second song with admirable restraint and real icy-coldness.

This is late Autumn with no heat at all. Lili Chookasian has a very light

voice and her first entrance doesn't bode too well for what is to come. All

this brings some dividends when the orchestra shows a wonderful burst of

warmth, especially from the lower strings at "Bald werden die verwelkten"

("Soon the withered golden leaves"). In fact, the Philadelphia strings are,

and it should be no surprise, one of the glories of this recording and show

Chookasian up. If only she could sing as well as they do. At "Ich weine viel

in meinem Einsamkeiten" ("Long do I weep in my loneliness") hear also the

solo horn against the oboe picked out by Ormandy and then "Sonne der Liebe

willst du nie mehr scheinen" (Sun of love will you never shine again), where,

as with Lewis in the ape and graves section of the first song, Chookasian

is rather overwhelmed by the power of the orchestra.

I think Ormandy sees this work in symphonic terms. It's a view which is often

put forward by scholars which casts the first and second songs as first and

second movements, songs three, four and five running together as a kind of

scherzo-intermezzo third movement (fourth song as quasi trio to the other

two movements' scherzo), and the sixth song as fourth movement/finale. The

reason I see this in Ormandy's account is that he seems to see the third,

fourth and fifth songs in very much the same way, very little variation in

tone and approach from song to song, stressing the chinoisserie that is certainly

a feature of Mahler's orchestration. Then there is the fact that little of

the darker undertones Sanderling sees are brought out. There are some lovely

woodwinds at the start of "Von der Jugend" matched with Lewis's lighter delivery

paying great dividends. Unlike Schreier, however, he is much more the witness

than the participant and, especially in comparison, even more detached from

the words in "Der Trunkene im Fruhling". Schreier, for example, becomes quite

inebriated as the song goes on where Lewis stays as sober as a judge. It's

a valid view either way and the listener must decide but I prefer Schreier's

approach. It brings me in more to what is being depicted and this work must

involve the listener. Though let it be said there is a rare stepping inside

of the scene by Lewis at "Ja! Der Lenz ist da" (Yes ! Spring is here") and

he also manages a laugh when describing the bird's laughter.

In "Von Der Schoenheit" Chookasian struggles to make the words tell, not

least in the horses section which Ormandy takes very fast making her hang

on for dear life and then in the opening of "Der Abschied" there is some

lack of tragic weight, but this is in common with what appears to be the

philosophy behind Ormandy's performance. Again and again the stress is on

refinement, fastidiousness and polish and no praise can be too high for the

orchestra who bring really cultured playing to everything. Again Chookasian

seems under-involved. With Lewis any detachment could be looked on as a positive

stance but with Chookasian I feel it's simply that she isn't quite up to

the peculiar demands of this piece, never more so than in the challenge of

the last song where her rather one-dimensional singing and peripheral feeling

for the words tells most of all. Ormandy's polish is in evidence throughout

and a good example is his accompaniment of "Die Blumen blassen im Dammerschien"

("The flowers grow pale in the twilight"). He is very controlled too, helped

by a slightly faster tempo than we are used to, so that crucial line "Alle

sehnsucht will nun traumen" doesn't move us as it should. He also skates

too discursively over the wonderful bird section, a real example of his

refinement actually robbing the music of one of its most distinctive moments

-more "Ma Mere l'oye" than "Le Chant de la terre"- and although that

expressionist, "Pierrot Lunaire-like" section beginning "Es wehet kuhl" with

flute and string bass underpinning has a fine sense of stillness it has less

depth than it needs, so that when the music warms up there is less feeling

of respite. In the funeral march orchestral passage there is some extraordinary

music where Mahler pushes the boundaries of tonality to the limit but Ormandy

rather throws it away in pursuit of smooth edges. The overall tempo is too

quick also to make the effect it has to, though there is some wonderful playing

from the cellos at the climax, really digging in to their phrases. Which

is more than Chookasian does in the closing section. Her attention to the

words is not really close and her tone rather one-dimensional, not expressive

enough for music that expresses so much and Ormandy rather forces her on.

In sum this is a beautiful performance, especially from the point of view

of conductor and the orchestra. But there is more to this work than what

lies on the surface and Ormandy's apparent stress on symphonic aspects seems

to encourage him in his refinement of everything else. Lewis's detachment

at least seems to have point. He plays, as I said, the witness. Chookasian,

on the other hand, is witness rather, one suspects, because she doesn't know

how to get involved or indeed whether she should. On balance I think the

same applies to Ormandy who doesn't impress as a Mahlerian in this most elusive

of works and is only saved by his wonderful orchestra who, in spite of some

slightly faster tempi than we are used to, make this a performance to be

enjoyed for all I may not regard it as a front runner.

Mahler brackets a baritone as alternative to a contralto in songs two, four,

and six but this practice is still the exception. One reason must be the

fact that male and female singers alternating makes for greater contrast.

Another that the presence of great mezzos and contraltos down the years,

compared with fewer comparable baritones, have made the choice of a woman

automatic. But it could be said that it seems more natural for a man to be

relating these poems - the poet speaking - and there are three recordings

that take this option. Two of them are with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and

one with Thomas Hampson. Hampson is matched with Peter Seiffert and the City

of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra under Sir Simon Rattle on EMI (5 56200 2)

but I'm going to pass over this recording in favour of one of those with

Fischer-Dieskau.

For one thing the Rattle recording illustrates the problem of having

two voices that don't contrast enough. Hampson and Seiffert are fine singers

but they have voices that sound very alike. In addition both they and their

conductor, whilst giving a superbly prepared performance, don't really penetrate

into the fabric of this work when compared with the best of the rest. So,

with regret, because the recorded sound on this issue is perhaps the best

I have heard, I shall leave this aside. So far as the two recordings with

Fischer-Dieskau are concerned his earlier one with Murray Dickie and the

Philharmonia under Paul Kletzki on EMI is a lovely performance but is, I

believe, surpassed by his second where he is partnered by James King with

Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic and re-issued in a new

mastering by Decca on their "Legendary Performances" series (466 381 2).

The extra distinction in the conducting of Bernstein and the presence of

the Viennese adds lustre to this famous set.

For one thing the Rattle recording illustrates the problem of having

two voices that don't contrast enough. Hampson and Seiffert are fine singers

but they have voices that sound very alike. In addition both they and their

conductor, whilst giving a superbly prepared performance, don't really penetrate

into the fabric of this work when compared with the best of the rest. So,

with regret, because the recorded sound on this issue is perhaps the best

I have heard, I shall leave this aside. So far as the two recordings with

Fischer-Dieskau are concerned his earlier one with Murray Dickie and the

Philharmonia under Paul Kletzki on EMI is a lovely performance but is, I

believe, surpassed by his second where he is partnered by James King with

Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic and re-issued in a new

mastering by Decca on their "Legendary Performances" series (466 381 2).

The extra distinction in the conducting of Bernstein and the presence of

the Viennese adds lustre to this famous set.

James King is a Heldentenor, a Siegmund in the past, and the abandon he and

Bernstein adopt to tear into the first song is very impressive. Bernstein's

tempo is quite quick but does retain the "pesante" Mahler demands. He is

also aware of the intricate details in the orchestra, helped by a rich but

very analytical recording. At the first "Dunkel ist das leben" note the drop

in tempo so that when the opening bursts out again the effect is truly arresting.

King enunciates each word superbly too and is very passionate. "Das firmament

blaut ewig" brings a fine change in mood and only Bernstein matches Horenstein

with his vivid pizzicati at this point. There is wonderful string playing

right through, in fact, and every department of the VPO show them with this

music in their blood. In the ape on the graves section Bernstein and King

conspire to deliver the most expressionistic account of all, pushing the

music to the absolute limit. King is magnificent here with a visceral assault

on our emotions and notice the crunch on the final chord of all with the

pizzicati sounding like something out of the more recent avant garde.

In the second song the contrast could not be greater after what has followed.

The preparation before the entry of Fischer- Dieskau is superb. "Man meint,

ein kunstler habe Staub von Jade" ("One would think an artist had strewn

jade dust") brings a beautifully pointed description and what delicacy on

the word "ausgestreut". "Ein kalter wind beugt ihre Stengel nieder" ("an

icy wind bends down their stems") really sounds as though he is shielding

himself from the blast, so this is a subtlety dramatised account from

Fischer-Dieskau. Bernstein was never one to hold back when there is any emotion

going but it all seems more than appropriate here because he does know when

to pare the music down to almost nothing. "Mein Herz ist mude" ("My heart

is weary.") really does sound like a man at the end of his tether. The great

interpreter of Die Winterriese understand how to convey that in a song.

So this recording shows that two male singers can be made to contrast: King

heroic and passionate, Fischer-Dieskau reflective and elegiac. Bernstein

seems happy to be a man for all seasons and we will see this as a recording

that really explores opposites in this work, sometime polar opposites, to

a remarkable degree.

King bounces the third song along, all jaunty energy, and Bernstein's

accompaniment is ripe and chipper too, though they vary their approach in

the central section. This bounce is maintained in the fifth song but I must

say here I start to see the value of a little more subtlety, of irony like

with Schreier or Julius Patzak for Walter, though there is no doubt King

has the lung power those two singers lack. At "Der Lenz ist dar" ("Spring

is here") the playing of the VPO is a wonderful example of their total commitment

to this music.

Fischer-Dieskau's description of the girls in the fourth song realises the

necessity to draw us into the scene and see it through his eyes. A slightly

slower tempo from Bernstein brings dividends too with some lovely string

slides. But the horses section is a mad dash, as fast as possible, forcing

Fischer-Dieskau to hector and shout in the manner of a PE instructor and

I didn't enjoy this one little bit. The return of the opening material for

the close is even more poignant, however. Did Mahler write any music sweeter

than this ?

Bernstein is surprisingly sharp in the opening of "Der Abschied", not doom-laden

as many often are. There is such experience in Fischer-Dieskau's opening

lines to follow this. He easily manages the trick of staying one step back

from the scene, as I think the singer should here, but also to invest it

with deeper meaning. Here I felt Hampson for Rattle stayed one step back

but nothing else, so there was a cold detachment which was inappropriate.

"Oh sieh ! Wie eine Silberbarke schwebt der mond" is then floated like the

moon it describes and it is as if Fischer-Dieskau first steps into the scene

at this point. In the passage describing the birds Fischer- Dieskau picks

out words pointedly and Bernstein paints the scene vividly, as he does later

when the central interlude starts. There are some really extreme sounds here

again.

The great lieder singer Fischer-Dieskau is comes to the fore in "Er stieg

vom Pfred und reichte ihm den Trunk" ("He dismounted and gave him the parting

cup") in its intimate simplicity and so it is with the rest of the great

closing passage. Again we sense the great contrast achieved by matching

Fischer-Dieskau with King. The recording balance of the voice here and elsewhere

is forward compared with others so it's like having Fischer-Dieskau in the

room with you. This adds intimacy in those parts where intimacy is appropriate,

but can be wearing where it is not. This latter is also an the impression

I am left with by James King and, in his case, it isn't just a question of

the recording balance. His heroic tenor might project the extrovert music

superbly, but on repeated hearings it can become tiring and it can lead to

a slight skating over of those passages in his songs where some intimacy

is needed. So, in this recording it's the tenor who is the weaker link. But

Fischer Dieskau is special and his contribution among the finest available.

Bernstein's view also is to be relished, especially its awareness of the

nervy tensions inherent in this music, one that is sometimes ignored. As

so often with him in Mahler this is a roller-coaster ride. But there are

few, if any, passages where this is anything other than illuminating and

enhancing.

That prince among Mahlerians Jascha Horenstein never recorded this

work commercially. Like so much else in his recording activities the catalogue

of missed opportunities that deprived us of, among other things, an integral

recorded Mahler cycle got in the way. Fortunately he made a studio recording

for the BBC in Manchester with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, John

Mitchinson and Alfreda Hodgson under near ideal conditions in 1972 a year

before his death. Through the activities of those with their eyes on the

main chance, unofficial issues have appeared and you can find two of them

on Music and Arts (CD 728) and Descant (Descant 01 - available through Berkshire

Record Outlets). The orchestra had never played the work so Horenstein was

given time to rehearse them thoroughly and the results pay dividends. This

is an expansive performance but the degree of space Horenstein gives the

music, allied especially with the familiar fingerprint of choosing modular

tempi to suit an entire movement, takes us deeper into this music than many

others can. Note the more trenchant tempo from the start of "Das Trinklied

vom Jammer der Erde" leading to the dragging on the strings at "erst sing'

ich euch ein lied" ("first I will sing you a song"). Then when Mitchinson

reaches "liegen wust die Garten der Seele" ("the gardens of the soul lie

waste") you really believe they do. Right the way through this first song

the tread is heavier, the weight of the world greater, the mood reflective.

To some this might take a little getting used to but persistence brings rewards.

Not least in the change of mood with the third stanza "Das firmament blaut

ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") and the opportunity Horenstein gives

himself to mark emphatically the pizzicati in the short passage while the

singer is silent. Evidence of his care for inner detail allied to outer

structure. Mitchinson delivers these words as a lament, tear-stained with

his care at "Du aber mensch, Mensch, wie lang lebst denn du ?" ("But thou,

o man, how long wilt thou live ?") penetrating as a question like no others.

The section describing the ape on the graves is terrifying with unease carried

over to the very end.

That prince among Mahlerians Jascha Horenstein never recorded this

work commercially. Like so much else in his recording activities the catalogue

of missed opportunities that deprived us of, among other things, an integral

recorded Mahler cycle got in the way. Fortunately he made a studio recording

for the BBC in Manchester with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, John

Mitchinson and Alfreda Hodgson under near ideal conditions in 1972 a year

before his death. Through the activities of those with their eyes on the

main chance, unofficial issues have appeared and you can find two of them

on Music and Arts (CD 728) and Descant (Descant 01 - available through Berkshire

Record Outlets). The orchestra had never played the work so Horenstein was

given time to rehearse them thoroughly and the results pay dividends. This

is an expansive performance but the degree of space Horenstein gives the

music, allied especially with the familiar fingerprint of choosing modular

tempi to suit an entire movement, takes us deeper into this music than many

others can. Note the more trenchant tempo from the start of "Das Trinklied

vom Jammer der Erde" leading to the dragging on the strings at "erst sing'

ich euch ein lied" ("first I will sing you a song"). Then when Mitchinson

reaches "liegen wust die Garten der Seele" ("the gardens of the soul lie

waste") you really believe they do. Right the way through this first song

the tread is heavier, the weight of the world greater, the mood reflective.

To some this might take a little getting used to but persistence brings rewards.

Not least in the change of mood with the third stanza "Das firmament blaut

ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") and the opportunity Horenstein gives

himself to mark emphatically the pizzicati in the short passage while the

singer is silent. Evidence of his care for inner detail allied to outer

structure. Mitchinson delivers these words as a lament, tear-stained with

his care at "Du aber mensch, Mensch, wie lang lebst denn du ?" ("But thou,

o man, how long wilt thou live ?") penetrating as a question like no others.

The section describing the ape on the graves is terrifying with unease carried

over to the very end.

After such a performance of the first song the second comes across even colder

than usual, more akin to despair. There should now be no question that

Horenstein's view of this work is darker and tinged with tragedy. The phrasing

of the oboe is exemplary in its lamenting quality as Horenstein continues

his deep analysis. Alfreda Hodgson's first entry is unobtrusive, her voice

darker and more earthy than the previous two we have considered. This is

surely the kind of voice Mahler must have had in mind. There is a surge of

feeling at "Bald werden die verweltkten goldnen Blatter" but no real warmth

so I think Horenstein wants to stress the utter loneliness in the poem. The

suitability of Hodgson's voice shows again at "Ich hab' Erquickung" ("I need

refreshment") with a really earthy tone and even the one point where most

interpretations relax the mood, the one point where the poem shows some hope,

"Sonne der liebe willst du nie mehr scheinen ?" ("Sun of love will you never

shine again ?"), the stress seems to be on hope rather than promise - a vain

hope, too.

In "Von der Jugend" Mitchinson lightens his approach revealingly but Horenstein's

slightly held-back accompaniment reveals more of the darker,

angst-beneath-the-surface quality. Note too a sight drag on the rhythm, and

in the central stanza, where the singer observes the surface of the pond,

Horenstein and Mitchinson become very reflective. In the fourth song Hodgson's

opening is as good an example as any of her feeling for words and Horenstein

gives her just the space she needs. At last a singer in these songs that

can match her partner. The horses section is steadier than usual and so Hodgson

keeps up and gets her words in without problems. Also Horenstein can mark

the slightly unhinged quality of this passage, not usually noted. You are

also aware that this song, like the previous one, has three parts and I love

the half- tone Hodgson adopts at the end allowing us to hear the lovely high

strings and woodwinds. Horenstein closes the movement as you would expect,

a real awareness of winding down. He is also wonderful at the chamber-like

textures, helped by the closer-in recording, but surely as much a tribute

to him. This is also true of the fifth song. Note the plaintive woodwind,

cawing like birds. Again there is more drag, but every detail tells and the

mood remains analytic and elegiac all at once.

The opening of "Der Abschied" is doom-laden promising a heavy journey ahead.

In fact it's worth noting Horenstein's performance clocks the longest span

of all. There are passages when time seems to stand still in an almost Zen-like

stasis. Hodgson enters almost with fear, as if she is going to cause the

world to end if she sings too loudly. The passage describing the birds ("Die

vogel hocken still in ihren Zweigen") shows a conductor steeped in the Viennese

tradition of that time and what conducting and playing there is too around

"Es wehet kuhl im Schatten meiner fichten", the words almost whispered by

Hodsgon and the feeling of rapt expectation extraordinary. We know this

remarkable performance was done in one take, as if it was in front of a live

audience, but I don't think I have ever heard this amazing passage, where

Mahler pares everything down to a few instruments, taken so slowly and with

such concentration. It's hard to find words adequate to describe the final

pages. Taken at as slow a tempo as could be dared, soloist, conductor and

orchestra sustain a line that is unutterably moving. According to John Mitchinson

in a later interview most of the orchestra were in tears at the close.

So, we have a performance where both soloists compliment and balance each

other and are matched with a conductor whose own contribution is one of the

greatest ever committed to tape. This was a special work to Horenstein who

first heard it in Vienna in 1918 conducted by Mengelberg. He was never the

conductor for the easy option, though. He expected an enormous amount from

everyone, including the listener, and it is the case that many of his recordings

don't reveal their secrets on first encounter and that is the case here.

I really cannot recomend this recording too highly. It's one for the long

haul, one that will reveal its greatness over time. Some may find Horenstein's

tempi, especially that for the first song, on the slower side of acceptable.

For me the tempi are natural and what is more important there's never any

strain in the playing or the singing because of it. It's clear an immense

amount of preparation went into this and that the decision to perform without

retakes paid dividends. The sound is analytical, tailored for broadcast,

but this only accentuates Horenstein's way with the chamber textures with

every detail is exposed by his gimlet eye. This is a performance that penetrates

to the very core of this work, the time in which it was written and the man

who wrote it. It reaches to the core of the listener also. The orchestra

is the only weak link. They play well and have the benefit of being the clean

sheet on which Horenstein wrote his interpretation but they don't have the

corporate elan of one of the great international ensembles. However, surface

sheen, as we saw with Ormandy and his Philadelphians, is not everything.

Five years after the Horenstein studio broadcast the

BBC Northern Symphony performed the work "live" at the Free Trade Hall in

Manchester with John Mitchinson again but this time with Raymond Leppard

conducting and, the real gem of the recording, Janet Baker. This appeared

a few years ago on BBC Radio Classics and has become available again on a

reissue of some of that series, BBC Classics Collection (BBCM 5012-2). We

can speculate on how much Horenstein's influence was still with these players

but it would be nice to think many of them carried the experience of working

with him for they play the work well under a conductor not usually associated

with Mahler. Leppard presses forward in the first song more than Horenstein,

is more energetic than many others. I love the cackling woodwind against

the opening horn figure each time it re- appears and Mitchinson is encouraged

to be more dynamic and energetic. "Das firmament blaut ewig" retains that

sense of forward movement, not pausing for repose, but manages to pick out

fine detail. It may be the presence of an audience that makes him really

project the words so the ape on the graves section receives more hysteria

than it did with Horenstein. Perhaps the orchestra is lacking in the bass

department but the gain in higher frequencies of the shriller aspects of

the music is illuminating.

Five years after the Horenstein studio broadcast the

BBC Northern Symphony performed the work "live" at the Free Trade Hall in

Manchester with John Mitchinson again but this time with Raymond Leppard

conducting and, the real gem of the recording, Janet Baker. This appeared

a few years ago on BBC Radio Classics and has become available again on a

reissue of some of that series, BBC Classics Collection (BBCM 5012-2). We

can speculate on how much Horenstein's influence was still with these players

but it would be nice to think many of them carried the experience of working

with him for they play the work well under a conductor not usually associated

with Mahler. Leppard presses forward in the first song more than Horenstein,

is more energetic than many others. I love the cackling woodwind against

the opening horn figure each time it re- appears and Mitchinson is encouraged

to be more dynamic and energetic. "Das firmament blaut ewig" retains that

sense of forward movement, not pausing for repose, but manages to pick out

fine detail. It may be the presence of an audience that makes him really

project the words so the ape on the graves section receives more hysteria

than it did with Horenstein. Perhaps the orchestra is lacking in the bass

department but the gain in higher frequencies of the shriller aspects of

the music is illuminating.

Mitchinson and Leppard are especially perky in the "Von der Jugend". A lightening

of tone after what has preceded and you feel Mitchinson is freer to smile

more than he did under the rather glum Horenstein. Leppard is, I think, a

more approachable character with less early-century Viennese angst. Again

in the fifth song Mitchinson and Leppard go for energy. I found the delivery

of the passage starting at "Ein Vogel singt im baum" contained a real Wunderhorn

quality reminiscent of the Third Symphony's third and second movements. Leppard

should be congratulated for noticing this.

When Janet Baker makes her first appearance in the second song we are in

the presence of one of the greatest of all Mahler interpreters, one of the

great voices of the century. Note even in her first line there is no

tentativeness. Her interpretation is formed from the very first word with

meaning in every syllable. Her tone also is so full it has the effect of

shifting the entire attitude of this movement to something more than just

a description of loneliness to the act of being lonely. We are made to feel

through the singer and so are made to care about the character. This is an

aspect of interpretation you would expect a great singer like Baker to bring

out. Listen in "ein kalter wind beugt ihre Stengel nieder" ("an icy wind

blows down their stems") how she halves her tone for the last words and likewise,

after the outpouring at "Sonne der Liebe willst du nie mehr scheinen", she

tempers this in the same way at "mild aufzutrocken" ("my bitter tears") with

almost a whisper. It is as if the bitter tears have only just been discovered.

Few singers, if any, can describe the young girls playing by the river in

"Von der Schoenheit" like Baker. You have to hear to believe how her phrasing,

lilt and the special magic of her voice makes this passage stick in the mind.

An openness of heart is the best description. Notice the slight pause on

the word "Neckerein" ("teasingly"). That kind of artistry is denied to many

singers. She can even hang behind the beat a little in "spielgt sie im blanken

Wasser wieder" ("and reflects them in the clear water").

Sheer weight of tone is rather missing from the tolling at the start of "Der

Abschied". It could have done with a little extra funeral tread for Leppard

is less good on tragic weight in this work. But when Baker enters any

reservations must be put aside. There is an immense contrast between the

last time we heard her and now and this ability to cover a whole world of

meaning and mood is one of the many reasons why she is so great in this work

The long orchestral interlude perhaps finds Leppard falling some way short

of his more illustrious colleagues but he acquits himself very well for all

that. The recording balance favours the winds and they play with great character,

if not with the cultured tone you would expect from one of the great Mahler

ensembles, but that was true also of their account for Horenstein. "Er stieg

vom Pferd und reichte ihm den Trunk" ("He dismounted and gave me the parting

cup") is a token for what is to come since Baker's account of the final part

of this work surpasses everything she does and that was formidable enough.

Again her ability to vary her tone and dynamics and to pick out each word

and phrase is uncanny and deeply moving.

Janet Baker's great contribution is the finest part of this "live" recording

but Mitchinson, so very good for Horenstein, also projects a more confident,

extrovert account this time, showing him to be a great and flexible artist

whilst not quite matching this partner as he did Hodgson. Leppard too, it

must be said, is a revelation. That is not a case of damning with faint praise.

His background at this time was in other repertoire but you would never know

it and what he may lack in Mahlerian depth he makes up for in innate musicianship

and obvious love of the work.

This is not the only recording featuring Janet Baker. Her studio recording

is on Phillips with the Concertgebouw Orchestra under Bernard Haitink and

James King as her tenor partner. This is currently only available coupled

with Haitink's fine account of Mahler's Ninth which makes it less competitive.

There is no doubt the presence of one of the great Mahler orchestras gives

this a head start over the recording with Leppard, but I think that is all

it has in its favour. Janet Baker's contribution on the Leppard recording

has more reach, depth and eloquence, added to by the presence of an audience.

James King has the Heldentenor's voice many believe these songs demand but

I think he's better heard on the recording with Leonard Bernstein and the

Vienna Philharmonic. Haitink supports both singers superbly and those who

believe his considerable Mahlerian credentials make him more suited to this

work than Leppard need not hesitate. Here is Janet Baker in her glory, after

all. But for real greatness from her point of view my advice is to seek out

the Leppard recording because he is by no means shamed by comparison with

Haitink. In fact, there are passages where his slightly more astringent approach

is to be preferred.

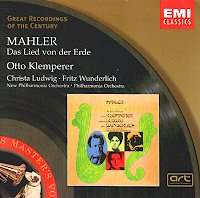

Otto Klemperer recorded the work twice commercially, but it's his

second recording for EMI which is the one to consider, especially now it's

been remastered for EMI's "Great Recordings of the Century" series (CDM 5

66892 2). Clarity and richness are the keynotes of his approach in the opening

of the first song with a wonderful density and weight to support Fritz

Wunderlich's golden, well-microphoned tenor. His first "Dunkel ist das Leben"

is lamenting and lyrical but it's the passage "Ein voller Becher Weins zur

rechten Zeit" ("A brimming cup of wine at the right time") with a more insistent,

ardent delivery that is the best representative of his wonderful contribution

to this work, I believe one of the finest on record. Notice also the woodwind

in the second "Dunkel ist...." where Klemperer's practice of giving prominence

to all the woodwind in his special sound palette accentuates the chamber

textures of this work to a remarkable degree. Since the players concerned

are so good this is a big plus in this great recording. In the orchestral

passage before "Das firmament blaut ewig" Klemperer, for all the astringency

of his sound palette, sounds more exotic than most giving echoes of passages

in the Seventh Symphony. Here also Wunderlich makes us aware of every word

in the text. Notice too the cor anglais and the flutter-tongued flutes, never

better caught or heard than here. Wunderlich might not have the lung power

of the Heldentenor but manages with his artistry and clear diction to deliver

the ape on the graves section in as manic a fashion as could be wished with

real terror from Wunderlich.

Otto Klemperer recorded the work twice commercially, but it's his

second recording for EMI which is the one to consider, especially now it's

been remastered for EMI's "Great Recordings of the Century" series (CDM 5

66892 2). Clarity and richness are the keynotes of his approach in the opening

of the first song with a wonderful density and weight to support Fritz

Wunderlich's golden, well-microphoned tenor. His first "Dunkel ist das Leben"

is lamenting and lyrical but it's the passage "Ein voller Becher Weins zur

rechten Zeit" ("A brimming cup of wine at the right time") with a more insistent,

ardent delivery that is the best representative of his wonderful contribution

to this work, I believe one of the finest on record. Notice also the woodwind

in the second "Dunkel ist...." where Klemperer's practice of giving prominence

to all the woodwind in his special sound palette accentuates the chamber

textures of this work to a remarkable degree. Since the players concerned

are so good this is a big plus in this great recording. In the orchestral

passage before "Das firmament blaut ewig" Klemperer, for all the astringency

of his sound palette, sounds more exotic than most giving echoes of passages

in the Seventh Symphony. Here also Wunderlich makes us aware of every word

in the text. Notice too the cor anglais and the flutter-tongued flutes, never

better caught or heard than here. Wunderlich might not have the lung power

of the Heldentenor but manages with his artistry and clear diction to deliver

the ape on the graves section in as manic a fashion as could be wished with

real terror from Wunderlich.

Klemperer holds back his tempo for "Der Einsame im Herbst" with the opening

woodwinds like lamenting crows on the branches. Forget Autumn, Winter is

here already. This reminds us perhaps of Klemperer's life-long battles with

manic-depression after the extroversion of the first song. Christa Ludwig

matches Fritz Wunderlich in artistry and we are aware immediately that this

recording boasts two singers of equal stature. Listen to the wonderful solo

flute in this movement. At that time the Philharmonia retained Gareth Morris

as Principal. He played a wooden instrument whose sound Klemperer was very

fond of, unlike many colleagues. Ludwig is balanced a little further back

than Wunderlich so her contribution takes on the air of a duet with the woodwind

soloists. Her feeling for words matches Wunderlich's, though, and is almost

as great as Baker's. I liked, for example, her slight hesitation on "Ein

kalter wind beugt ihre Stengel nieder" ("An icy wind bends down their stems")

and her description of the little lantern is exemplary, recognising this

as a central image of the song. Then "Ja, gib mir ruh...." ("Yes, give me

rest....") really shows the range of her voice - every timbre from high to

low. The eloquence of Klemperer's interpretation shows even more in "ich

weine viel..." with the orchestra and soloist in perfect accord and only

Klemperer encourages the horn to snarl in the final line: a worm in the roses

of the last flowering. Typically Mahler, typically Klemperer. It's interesting

how it's the really great Mahler conductors who make the most of this elusive

second song. Too often it can sound dry and anonymous after the ripeness

of the first. Klemperer invests every bar with interest and Ludwig supports

him.

The third song brings with it what might be a problem for some and that is

the slower tempi Klemperer adopts. In this song I think it brings dividends

in the feeling that every detail of Mahler's orchestration glitters, but

there is some loss in energy. On the other hand it allows Wunderlich to take

his time over every word and for us to enjoy that. Also, as the song uncurls

itself, you become more aware of the darker shadows, more of the Viennese

angst, behind the ostensibly Chinese imagery.

At the start of "Von der Schoenheit" there is lovely detail in the high strings

showing what a rich recording this was and how well it has come up in the

new transfer. Ludwig is almost as fine as Baker in the opening description

with a lovely, chesty tone but that slower tempo we noticed in the previous

song becomes a problem in the horses section. One effect is that Ludwig has

no problems and we are also able to hear some remarkable details from the

orchestra. But these do sound like old nags the young men are riding. Much

is redeemed at the close, however, for at "In dem Funkeln ihrer grosen Augen"

("In the flashing of her large eyes") Ludwig really describes the girl as

if a camera has zoomed in on one face in the crowd. A fine example again

of a singer knowing how to direct the attention of the listener to the points

that really matter.

Extraordinary woodwind again at the opening of "Der Trunkene im Fruhling",

close in like a chamber group. Klemperer marks well the slightly off-beat

in this song in spite of, again, a slower overall tempo than we are used

to. But "Ein vogel singt ...." brings a lovely lightening of tone from

Wunderlich, a real touch of fantasy. He doesn't really sound drunk, though,

as does Schreier. Just rather tipsy.

With the heavy tolling of harp and gong at the opening of "Der Abschied"

the impression is that Klemperer has decided on the most sombre of moods.

Ludwig is very pure and ethereal in her opening and again her partnership

with the solo flute is unforgettable. The oboe also is haunting. Soon after

this the passage beginning with "Der bach singt voller...." ("The brook sings

loud....") finds Klemperer picking the piece apart. It's rather like inviting

an old friend around who then proceeds to submit you to deep analysis. This

is perhaps the most remarkable account of the section describing the birds

with every sound made to count. Klemperer also makes sure the mandolin is

given prominence. It seems to be the older generation who do this. Maybe

they still recalled how novel it was to hear this instrument all those years

ago.

The funeral march passage is heavy with a very special irony. Not easy to

describe but there is distinct mordancy about the timbre Klemperer adopts.

The feeling I always have is that Klemperer regarded this passage as something

of a centre piece of this work, token of his darker view of the work. But

this doesn't detract from the closing pages which bring a wonderfully ecstatic

reading from Ludwig, Klemperer and the orchestra. This close is not the sad

farewell that it often seems but a real liberation of spirit.

So Klemperer's recording finds an almost perfect balance between the singers.

Wunderlich has a wonderfully golden tone with every word clear. Maybe he

doesn't dramatise as much as Schreier, or Mitchinson, but his is one of the

greatest accounts. Ludwig has a wonderfully deep tone and keen awareness

of the words surpassed only by Baker on record. This recording also gives

a superb orchestra the chance to record a reading that accentuates the textures

to a remarkable degree. Every strand is audible while at the same time supporting

Klemperer's less-emotional, more analytical response. For those wishing to

hear every detail of the score this is certainly the recording to have because

the playing is the best on record. Some might find the woodwind balanced

too close but since they play so well, and fit so well with what Klemperer

is trying to do, few ought to complain. Some of Klemperer's tempi are very

deliberate, the middle songs especially, and there's no denying this has

an effect on the lighter elements, but this would not be the reading it was

if they were different. This recording must be taken as it stands.

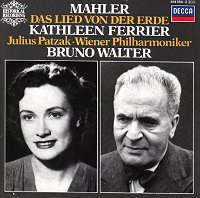

Experienced Mahlerites will have noticed there are two names so

far missing from this survey: Bruno Walter and Kathleen Ferrier. Walter gave

the first performance of the work in 1911 and there are five extant recordings

of him conducting it that are taken "off-the-air" in Europe and the USA.

He recorded it officially for commercial release three times. The first was

"live" in Vienna in 1936, the second in the studio in Vienna in 1952, the

last in a New York studio in 1960. Of these the 1952 Vienna Philharmonic

recording on Decca (414 194-2) is the most famous in that it records in the

contralto songs the interpretation of Kathleen Ferrier who Walter admired

from performances in New York and Edinburgh. Ferrier was terminally ill when

she recorded this and died a few months later. This fact, added to her undoubted

artistry and the unique quality of her voice, lends a special emotional charge

to the recording, one which has elevated it to a status granted few others.

Her tenor partner is Julius Patzak, a great artist who was also just past

his prime when this recording was made and is rather overwhelmed by the orchestra

at the start. There is such character in his voice and delivery that this

sweeps many doubts away. His first "Dunkel ist das leben" has a sweet melancholy

to it, for example. Like many of his colleagues Patazk is no Heldentenor,

but I'm now convinced this is not as important as awareness of words and

that ineffable thing called character, both of which Patzak has in abundance

even if his voice shows signs of strain. "Das firmament...." finds him in

reflective mood and Walter pares down the accompaniment for him beautifully,

but the ape on the graves section finds Patzak very strained. You could argue

this adds to the sense of drama, character and worldly-sickness, but after

too many hearings it can wear a little. Walter is wonderfully thrusting in

this movement, though. In fact the further back you go in Walter's recording

career the faster he seems to go.

Experienced Mahlerites will have noticed there are two names so

far missing from this survey: Bruno Walter and Kathleen Ferrier. Walter gave

the first performance of the work in 1911 and there are five extant recordings

of him conducting it that are taken "off-the-air" in Europe and the USA.

He recorded it officially for commercial release three times. The first was

"live" in Vienna in 1936, the second in the studio in Vienna in 1952, the

last in a New York studio in 1960. Of these the 1952 Vienna Philharmonic

recording on Decca (414 194-2) is the most famous in that it records in the

contralto songs the interpretation of Kathleen Ferrier who Walter admired

from performances in New York and Edinburgh. Ferrier was terminally ill when

she recorded this and died a few months later. This fact, added to her undoubted

artistry and the unique quality of her voice, lends a special emotional charge

to the recording, one which has elevated it to a status granted few others.

Her tenor partner is Julius Patzak, a great artist who was also just past

his prime when this recording was made and is rather overwhelmed by the orchestra

at the start. There is such character in his voice and delivery that this

sweeps many doubts away. His first "Dunkel ist das leben" has a sweet melancholy

to it, for example. Like many of his colleagues Patazk is no Heldentenor,

but I'm now convinced this is not as important as awareness of words and

that ineffable thing called character, both of which Patzak has in abundance

even if his voice shows signs of strain. "Das firmament...." finds him in

reflective mood and Walter pares down the accompaniment for him beautifully,

but the ape on the graves section finds Patzak very strained. You could argue

this adds to the sense of drama, character and worldly-sickness, but after

too many hearings it can wear a little. Walter is wonderfully thrusting in

this movement, though. In fact the further back you go in Walter's recording

career the faster he seems to go.

Walter presses on more than Klemperer in the second song also but paints

as bleak a picture as any. Ferrier's entrance is as memorable as Baker's

and establishes its magic from the start. "Ein kalter wind...." chills, "ein

herz ist mude" is given more deeper meaning than many. However, like Patzak

she shows strain, especially in "Sonne der liebe...". What matters is how

far we are prepared to forgive her faults for the unique experience we are

offered. Walter's tempo is much more suited to the middle songs than Klemperer's

and in his songs Patzak has a wonderful line in sly confidence. This is the

gnarled old philosopher, still in his cups from the tavern, nose pressed

up against the metaphorical windows watching his betters enjoying themselves.

Ferrier's description of the girls bathing is warm and involved, not as much

as Baker's, but enough. She seems to manage the horses section better than

most, maybe because Walter gives her just enough time. In the closing pages

you hear why a voice like Ferrier's was so suited to this work but, though

it pains me to say, the past tense is never more apparent than here.

There's no doubt in my mind that this famous recording needs to be on the

shelf of serious Mahlerians. I am equally sure that, in all conscience, I

cannot offer it as a benchmark choice. Hearing it again in such close proximity

to so many other great recordings has caused me to alter my opinion of it

slightly but profoundly. Ferrier and Patzak are both past their best, both

showing signs of some distress. In addition to this, surprisingly, the Vienna

Philharmonic Orchestra are a drawback. Not to put too fine a point on it,

they just don't play very well. There is insecurity in the woodwind and the

strings are undernourished and insecure. This was still post-war Vienna,

the orchestra hadn't really recovered from its wartime depravations and the

Decca recording doesn't help them in being rather brittle and papery. I think

the time has come for this recording to be allowed to take a second row seat

in our considerations, remain there for enrichment, for the special quality

of Ferrier especially, but to sit back and allow others to represent Mahler's

masterpiece more fittingly on-stage. Those who wish to have a better recorded

and played version of this work conducted by Bruno Walter should investigate

his 1960 stereo recording with Ernst Haefliger, Mildred Miller and the New

York Philharmonic Orchestra on Sony (SMK 64455). A fine performance well

recorded but one which does not, in my opinion, quite stand comparison with

the best of those already dealt with. The main problem is Mildred Miller

who I think is relatively uninvolved, though others disagree with me.

Those interested in historic recordings of this work must investigate Bruno

Walter's "live" 1936 recording made in Vienna (Dutton CDEA 5014 or Pearl

CD 9413) with the pre-war Vienna Philharmonic and soloists Charles Kullmann

and Kerstin Thorborg who would all would propel this recording into my front

rank were it not a question of the limited audio. As well as this there is

an even better "live" recording from Amsterdam in 1939 where the Concertgebouw

Orchestra is conducted by Carl Schuricht (Archiphon ARC-3.1 or Grammofono

2000 AB 78553) with Thorborg, dark and elemental, again the contralto partnering

this time the superb Carl Martin Ohmann. Once more limited audio prevents

this remarkable recording making it into my short list. I include these two

recordings here because I believe they tell us much about Mahler performing

practice pre-war and open an artistic window on a world now lost. Here are

two of the three great Mahler orchestras in their golden eras, palpably still

in touch with the way they would have played under Mahler himself, and as

such of crucial importance to lovers of Mahler's music. The Schuricht recording

also records an infamous incident in a quiet section of the last movement

where a woman in the audience calls out to the conductor, much to the annoyance

of the rest of the audience: "Deutschland uber alles, Herr Schuricht !" Carl

Schuricht, a German, was a late replacement for a sick Willem Mengelberg

and the atmosphere in the hall, weeks after the outbreak of war, must have

been electric. Sarcastic protest against Schuricht's presence or support

for the monsters of Nazism that were sweeping away so much of the old Europe

that gave rise to the work being performed and the people who it honoured

? We shall probably never know. Whatever, the incident sends a shiver down

the back and lends an extra drama to what is already a remarkable performance

and reminds us that music had central importance in people's lives at that

time, and should do so now.

There are more recordings of this work but the ones I have dealt with in

detail are the ones I believe represent the very best and are not let down

by the contribution of one of the three protagonists. This is principally

why I have no place in my short list for otherwise fine recordings by Tennstedt

and Solti where I think the contribution of the contraltos is the fatal flaw,

or Giulini where it's the tenor who spoils things, along with a feeling that

the conductor isn't quite inside the piece. I've also left out Reiner because,

superb though his two singers are, on this occasion the conductor's legendary

coldness leaves me equally cold in a work where personal involvement is crucial.

I also believe Barenboim and Von Karajan aren't sufficiently Mahlerian enough

to allow their recordings to match the best. People whose opinion I value

sing the praises of Gary Bertini on EMI. His recording boasts the splendid

Ben Heppner as tenor soloist who can stand comparison with Schreier and

Wunderlich, but his mezzo is Marjana Lipovsek who let down the Solti recording

and I'm afraid does the same here. These are all very personal reactions

but, as I explained, this is a work that goes to the very core of personal

taste in all Mahlerians and I am no exception.

I'm hard-pressed to recomend one recording above all. If I could have Peter

Schreier and Janet Baker with the Philharmonia Orchestra of 1963 conducted

by Jascha Horenstein and recorded by Rattle's engineers "live" in the Amsterdam

Concertgebouw, I would be satisfied. Janet Baker is, in my view, the greatest

exponent of the contralto songs and for those of the tenor I would award

that palm to Peter Schreier from among those in my short list. But Fritz

Wunderlich is not far behind him and neither is John Mitchinson. The Leppard

recording is the one I reach for most often, followed closely by the Horenstein

and then the Klemperer. Horenstein goes far deeper than Leppard but their

orchestra is not of the top flight. Klemperer goes deep also, has a fabulous

orchestra and two great soloists, but he does slow down in those central

songs. For the best all round version go for Sanderling who approaches

Horenstein, has a fine orchestra, one very great soloist and one very good

one, and all in a nicely balanced recording. But no Mahlerian's library should

have only one, or even two, recordings of this endlessly fascinating and

moving work.

Selected Recordings

Peter Schreier, Birgit Finnila, Berlin Symphony Orchestra, Sanderling:

Berlin Classics (0094022BC).

Crotchet

Amazon

Richard Lewis, Lili Chookasian, Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy: Sony

(SBK 53 518)

Crotchet

Amazon

Fischer-Dieskau , James King , Vienna Philharmonic Bernstein: Decca "Legendary

Performances" (466 381 2)

Crotchet

Amazon

John Mitchinson, Alfreda Hodgson , BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra Horenstein:

Music and Arts (CD 728)

Crotchet

Amazon

Fritz Wunderlich, Christa Ludwig , New Philharmonia Klemperer: EMI

(CDM 5 66892 2)

Crotchet

Amazon

Julius Patzak, Kathleen Ferrier, Vienna Philharmonic Walter Decca (414

194-2)

Crotchet

Amazon

Kurt Sanderling's recording is with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra,

Peter Schreier and Birgit Finnila on Berlin Classics (0094022BC). The opening

of the first song, "Der Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde", ("Drinking Song of

Earth's Sorrow") is huge and commanding with a real weight of tone that pitches

us into the hurly-burly just as it should. Peter Schreier handles both the

louder, animated, more vigorous passages and then the softer, more lyrical

ones with equal flair and aplomb. So this is a very complete rendition of

the opening song. We know Schreier to be an artist of rare intelligence and

he shows this in spades. There is never a moment when he hasn't something

interesting to say about this work. True, he may not have a Heldentenor's

power but he makes up for this in dramatic point. For example, each repetition

of the line "Dunkel ist das leben, ist der Tod" ("Dark is life; dark is death")

that punctuates this movement as a bitter-sweet refrain, as if casting a

sidelong glance at popular song, finds a different tone from him each time,

the second an especially dying fall: a world of regret conveyed in one phrase

showing how alive he is to each nuance. In the passage beginning "Das firmament

blaut ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") I love the special treatment Sanderling

gives to the trumpets, representative of his care for instrumental detail

and an example of the support he gives Schreier's intelligent delivery. But

the passage that's the greatest test for the singer is that which describes

a nightmare vision of an ape crouching on graves in the moonlight. This is

wonderfully dramatised by Schreier without tumbling into melodrama. Notice

how he spits out the words "wild-gespenstische Gestalt" ("wild and ghostly

form"). There is a great sense of a climax reached and then a satisfying

return to lyricism for the close. This is all recognition that here is a

poem of extremes and that those extremes need to be mapped and framed by

the soloist and conductor which they are here in a deeply satisfying whole,

frightening and soothing all at once. A better start to this work could not

be imagined.

Kurt Sanderling's recording is with the Berlin Symphony Orchestra,

Peter Schreier and Birgit Finnila on Berlin Classics (0094022BC). The opening

of the first song, "Der Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde", ("Drinking Song of

Earth's Sorrow") is huge and commanding with a real weight of tone that pitches

us into the hurly-burly just as it should. Peter Schreier handles both the

louder, animated, more vigorous passages and then the softer, more lyrical

ones with equal flair and aplomb. So this is a very complete rendition of

the opening song. We know Schreier to be an artist of rare intelligence and

he shows this in spades. There is never a moment when he hasn't something

interesting to say about this work. True, he may not have a Heldentenor's

power but he makes up for this in dramatic point. For example, each repetition

of the line "Dunkel ist das leben, ist der Tod" ("Dark is life; dark is death")

that punctuates this movement as a bitter-sweet refrain, as if casting a

sidelong glance at popular song, finds a different tone from him each time,

the second an especially dying fall: a world of regret conveyed in one phrase

showing how alive he is to each nuance. In the passage beginning "Das firmament

blaut ewig" ("The heavens are ever blue") I love the special treatment Sanderling

gives to the trumpets, representative of his care for instrumental detail

and an example of the support he gives Schreier's intelligent delivery. But

the passage that's the greatest test for the singer is that which describes

a nightmare vision of an ape crouching on graves in the moonlight. This is

wonderfully dramatised by Schreier without tumbling into melodrama. Notice

how he spits out the words "wild-gespenstische Gestalt" ("wild and ghostly

form"). There is a great sense of a climax reached and then a satisfying

return to lyricism for the close. This is all recognition that here is a

poem of extremes and that those extremes need to be mapped and framed by

the soloist and conductor which they are here in a deeply satisfying whole,

frightening and soothing all at once. A better start to this work could not

be imagined.

Less remarkable but no less distinctive is Eugene Ormandy's recording

with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Richard Lewis and Lili Chookasian on Sony

(SBK 53 518). This recording sells at bargain price and so must be the main

recommendation for those on the most limited resources - more so than the

recording on Naxos conducted by Michael Halasz. Richard Lewis has less attack

than Schreier in the first song. He is more mellow and lyrical and Ormandy

matches him in being more lighter-toned than Sanderling, more concerned with

the singing line and communicating energy and lift. There is less contrast

between the varying sections of the song too. The passage starting with "Das

firmament blaut ewig" is delivered by Lewis with none of Schreier's special

irony and in the ape and graves section Lewis is a little overwhelmed by

the orchestra, well as he sings, where Schreier manages to ride the climax

admirably. Not surprisingly, Lewis doesn't have Schreier's distinctive delivery