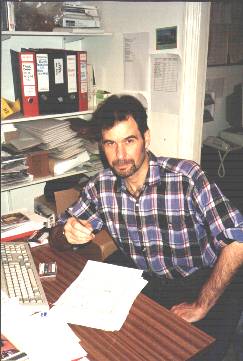

David Wishart at work in London

Music Webmaster Len Mullenger

David Wishart at work in

London

David Wishart's love of music led him into record retail almost from school.

He soon specialised in importing and selling film music. In 1984 he set up

his own label, Cloud Nine Records, releasing movie music and contemporary

classical works. He was soon consultant to a number of major recording companies

including Silva Screen and EMI. He has penned the sleeve notes for over one

hundred and fifty film music and classical albums and regularly pens reviews

and writes articles on film music for a number of leading journals. He has

produced over one hundred albums of various kinds and has produced or co-produced

seventy film music and classical recordings with orchestras ranging from

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, The Philharmonia, The Westminster Philharmonic,

The Pecs Hungarian Symphony Orchestra, The Royal Ballet Sinfonia, The BBC

Symphony Orchestra and The City of Prague Philharmonic.

|

Left: David Wishart at the FHS recording

studio in Prague

Right: Recording the soundtrack score for "The Gambler" Left to right: Karoly Makk (film director), Gerard Schurmann (composer), Marc Vlessing (film producer), Mike Ross-Trevor (recording engineer), David Wishart (music producer) |

|

Richard Adams: I would guess you were a film music enthusiast long

before you became involved in the recording industry. When did you first

start listening to film music and do you remember which scores and composers

attracted you initially?

David Wishart: Like most youngsters in Fifties Britain, I was getting precious little musical education at school; we were merely coerced into singing folk songs, and that was about it. Whilst I liked pop and rock music (and still do), I was nevertheless drawn almost subconsciously toward symphonic music - and the only place I heard that was at the movies. And as I went to the cinema as often as I could, I got to hear a great deal of film music. The first score which really made an impression was THE LAST COMMAND composed by Max Steiner. The film was on during the school holidays and I think I saw it four times during the one week. The other half of the "double-bill" was MUTINY, with music by Dimitri Tiomkin, but that score made less of an impression - although Tiomkin was soon to become a firm favourite of mine - how could I resist THE ALAMO and THE GUNS OF NAVARONE? By the time I was fifteen I thought I knew all there was to know about film music!

RA: How did you first become involved in producing film music recordings?

DW: As a purchaser of film music - in the good old days of the LP - I was invariably disappointed with the packaging; the album covers usually had a splendidly lurid reproduction of the given film's poster but turn the sleeve over and ... well, not much really. It was really my desire for extensive ... or even some ... liner notes that led me to set up my own label, Cloud Nine Records. I started out by producing albums of previously unreleased film music derived from vintage studio tapes - but within a year I had produced my first recording. Since then I have persevered with my own label but have done most of my work for other record companies - most consistently for Silva Screen Records, for whom I have been a consultant for eight years.

RA: Have the recording companies that you've worked for been receptive to your ideas for film score recordings?

DW:

Silva Screen Records, although very commercially minded, is very receptive

to ideas - is very adventurous - and an exciting outfit to work for. Their

managing director, Reynold D'Silva, is not really a film music buff himself,

being more of a jazz enthusiast (and, of course, Silva has two superb jazz

labels), but he has extraordinary vision, and is willing to back a good idea

- even to the extent of funding more esoteric projects, mindful that prestige

albums, as well as patently commercial product, is good for the company image.

Most of Silva Screen's recordings are produced by the indefatigable James

Fitzpatrick - an ardent film music enthusiast - and, quite frankly one of

the best recording producers around - in any field; it was he who first mooted

the idea of Silva Screen signing the lovely opera singer Lesley Garrett,

and it was he who guided her to stardom via some outstanding compendium albums.

James is a good friend - of twenty year's standing - with whom I have a strong

and enjoyable working relationship - and both he and I share a background

in record retail. Silva Screen's other influential figure is the droll David

Stoner, who seems to know all there is to know about film and television

music, but has an extraordinary knowledge of classical repertoire as well;

David supervises the release of every Silva album but occasionally makes

a foray into the world of producing - most recently overseeing the recording

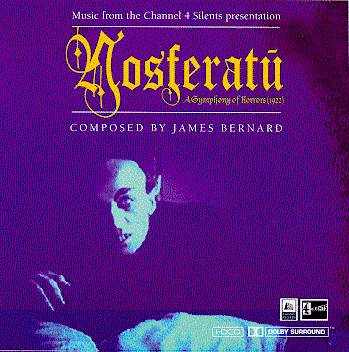

of the new score for the silent NOSFERATU by his old friend James Bernard.

But Silva aside, I have always been disappointed by my dealings with other

record companies - and in particular the majors. The BIG record companies

are rather set in their ways. They are always having meetings to produce

new initiatives but in general it seems to me that such meetings merely engender

other meetings and rarely effect the product end of the market. Film music

is seen by the majors as something of a nuisance - and their film music releases

are often no more than the fulfillment of contractual obligations. At one

end of a conglomerate you will have one division outlying a fortune to purchase

a massive film music catalogue - whilst at the other end of the same corporation

you have another division deciding that it is not worth releasing ninety-nine

percent of the recently (very expensive) acquisitions! Actually that is not

a generalization, I have witnessed this happen on three occasions! A major

record concern, with its pop and rock interests, gets into the mode of perceiving

sales for individual product in the hundreds of thousands - and it then becomes

difficult to see film music albums, with their "specialist" or limited appeal

as anything other than "time-wasters". Worse, they have no true experience

in marketing soundtracks or film music discs; of course they will say they

have by virtue of having released hundreds of movie scores over the years

- but herein lies the problem. Their film music discs have traditionally

been given to their traveling reps as just so much product - along with all

the company's other diverse releases - and film music really needs specialist

marketing. Of course, a hit film can engender a huge demand for a soundtrack

- and record companies can pat themselves on the back for producing TRAINSPOTTING

or TITANIC - but it is interesting to note that the huge marketing campaign

for the TITANIC album only really sprung into being AFTER Sony discovered

they had a hit on their hands. I recently worked on an album for a major

and provided them with all the information they might need to market this

particular disc; part of my brief to them was the addresses of all the film

music magazines I knew around the world (with individual reviewers names),

all the film magazines with reputable soundtrack columns - and just for good

measure, all the internet sites I knew who reviewed new film music albums.

A cursory check after three months revealed that NOT ONE of the addresses

on my list had received a promotional copy of this album - not even EMPIRE

magazine, the country's top-selling film mag - or FLICKS, which is a give-away

available in every cinema foyer in the land. The only journal to get the

disc was GRAMOPHONE; it can only be construed that in some perverse way the

company was trying to view this soundtrack as some sort of classical album.

It is insane to attempt to market a film music album and then not inform

film music or film magazines. The sting in the tail is that the company concerned

is very "disappointed" in the sales of the album! So, always look to the

specialist film music labels - Silva Screen, Varese Saraband, Intrada,

Prometheus, etc for the "committed" product. If the album comes from a major

company and it is well produced, well presented and well marketed ... well,

this is probably a fluke.

DW:

Silva Screen Records, although very commercially minded, is very receptive

to ideas - is very adventurous - and an exciting outfit to work for. Their

managing director, Reynold D'Silva, is not really a film music buff himself,

being more of a jazz enthusiast (and, of course, Silva has two superb jazz

labels), but he has extraordinary vision, and is willing to back a good idea

- even to the extent of funding more esoteric projects, mindful that prestige

albums, as well as patently commercial product, is good for the company image.

Most of Silva Screen's recordings are produced by the indefatigable James

Fitzpatrick - an ardent film music enthusiast - and, quite frankly one of

the best recording producers around - in any field; it was he who first mooted

the idea of Silva Screen signing the lovely opera singer Lesley Garrett,

and it was he who guided her to stardom via some outstanding compendium albums.

James is a good friend - of twenty year's standing - with whom I have a strong

and enjoyable working relationship - and both he and I share a background

in record retail. Silva Screen's other influential figure is the droll David

Stoner, who seems to know all there is to know about film and television

music, but has an extraordinary knowledge of classical repertoire as well;

David supervises the release of every Silva album but occasionally makes

a foray into the world of producing - most recently overseeing the recording

of the new score for the silent NOSFERATU by his old friend James Bernard.

But Silva aside, I have always been disappointed by my dealings with other

record companies - and in particular the majors. The BIG record companies

are rather set in their ways. They are always having meetings to produce

new initiatives but in general it seems to me that such meetings merely engender

other meetings and rarely effect the product end of the market. Film music

is seen by the majors as something of a nuisance - and their film music releases

are often no more than the fulfillment of contractual obligations. At one

end of a conglomerate you will have one division outlying a fortune to purchase

a massive film music catalogue - whilst at the other end of the same corporation

you have another division deciding that it is not worth releasing ninety-nine

percent of the recently (very expensive) acquisitions! Actually that is not

a generalization, I have witnessed this happen on three occasions! A major

record concern, with its pop and rock interests, gets into the mode of perceiving

sales for individual product in the hundreds of thousands - and it then becomes

difficult to see film music albums, with their "specialist" or limited appeal

as anything other than "time-wasters". Worse, they have no true experience

in marketing soundtracks or film music discs; of course they will say they

have by virtue of having released hundreds of movie scores over the years

- but herein lies the problem. Their film music discs have traditionally

been given to their traveling reps as just so much product - along with all

the company's other diverse releases - and film music really needs specialist

marketing. Of course, a hit film can engender a huge demand for a soundtrack

- and record companies can pat themselves on the back for producing TRAINSPOTTING

or TITANIC - but it is interesting to note that the huge marketing campaign

for the TITANIC album only really sprung into being AFTER Sony discovered

they had a hit on their hands. I recently worked on an album for a major

and provided them with all the information they might need to market this

particular disc; part of my brief to them was the addresses of all the film

music magazines I knew around the world (with individual reviewers names),

all the film magazines with reputable soundtrack columns - and just for good

measure, all the internet sites I knew who reviewed new film music albums.

A cursory check after three months revealed that NOT ONE of the addresses

on my list had received a promotional copy of this album - not even EMPIRE

magazine, the country's top-selling film mag - or FLICKS, which is a give-away

available in every cinema foyer in the land. The only journal to get the

disc was GRAMOPHONE; it can only be construed that in some perverse way the

company was trying to view this soundtrack as some sort of classical album.

It is insane to attempt to market a film music album and then not inform

film music or film magazines. The sting in the tail is that the company concerned

is very "disappointed" in the sales of the album! So, always look to the

specialist film music labels - Silva Screen, Varese Saraband, Intrada,

Prometheus, etc for the "committed" product. If the album comes from a major

company and it is well produced, well presented and well marketed ... well,

this is probably a fluke.

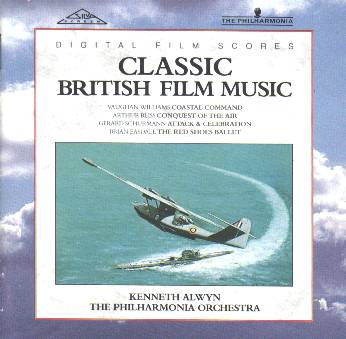

RA: How expensive is it to produce an album such as THE RED SHOES or THE BIG COUNTRY? You used of one of England's greatest orchestras, The Philharmonia, for both recordings. Was the orchestra a contributing factor to the cost of these discs?

DW: British orchestras are the finest in the world - and that is not just my opinion. Also, and this is indisputable, they are the best sight-readers. Why this should be I don't know. Inevitably British orchestras are relatively expensive - but are worth the outlay. It is cheaper to record in mainland Europe, but the kind of finesse associated with British playing takes longer to achieve. When you turn up at the studio with a British orchestra you are never concerned about aspects of the playing; you know it will be virtually perfect right from the onset. So yes, the costs on these albums were quite high - but whereas THE RED SHOES did not initially fare well, THE BIG COUNTRY - and LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, which Silva also recorded with The Philharmonia - recovered their costs very quickly indeed.

RA: Do you have many of the scores that you record reconstructed? Is this an expensive process? What does it involve?

DW: In the past when a record company has wanted to record a piece of film music, they would cast around to see if the music was at least available in full score - and most preferably with attendant orchestral parts. As most film music manuscripts have been lost to us, this has meant that the amount of film music recorded in the past has been restricted. I and my colleagues at Silva take a differing approach to recording. We decide what we want to record first - and if the music is not available - and usually it is not - then we reconstruct it with the permission of the publishers. This means we are free of previous restrictions; when record companies would only consider recording "what was available." I know that Silva Screen has reconstructed about seventy percent of its huge catalogue of recorded film music - more than a hundred and fifty titles - and that is a great deal of music which otherwise would just not exist. Of course, the process is not cheap - but Silva maintain a team of elite musicians adept at reconstructing either from composer sketches (which can sometimes be found) or from aural tracks taken from the films themselves - a painstaking process where the arranger has to effectively filter out the film's dialogue and sound effects and discern the exact instrumentation and texture of the score even when it is dubbed into the film at virtually an inaudible level. Meritorious mention should go to arrangers Philip Lane, Nic Raine, Paul Bateman, Derek Wadsworth and Mike and Kevin Townend. How do they do it!

RA: Your recording of THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN received good reviews but I feel it suffers from some less than professional orchestral playing. Why wasn't the Philharmonia used?

DW: Herein lies a tale. Reconstruction is a major protagonist. Silva had decided to undertake the full reconstruction of the classic "lost" Franz Waxman score (only a few sketches remained). This was in the days before the company had become totally conversant with the process and at the end of the day the reconstruction proved very expensive. At the time, The Philharmonia was Silva's chosen recording orchestra (I think the company engaged them on nine occasions) - and when the sums were done, it was deemed the project had become unviable. By the time a recording had been realised and marketing undertaken it seemed, on paper at least, that project would not recoup - certainly not for a long time. The reconstructed score and parts were shelved. After a couple of years I took down the score and thought ... perhaps there is a way to facilitate a recording reasonably inexpensively ... at least that way film music buffs would get an album of Waxman's score. I looked around for a suitable ensemble which could be contracted for non-union rates - and lighted on The Westminster Philharmonic Orchestra. They played many London concert dates (and the occasional international tour) and although they had union players most of the musicians were either retired from full-time professional engagements or excellent student virtuosi. Whilst it was obvious the level of playing could not match The Philharmonia it was nevertheless of a standard suitable for recording THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN. The subsequent recording sessions were different from the norm in that much more time was permitted for rehearsal - and whilst, as thought, the orchestra's precision was less than that exhibited by The Philharmonia, I was very impressed by the committed playing; THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN emerged in a very passionate performance. What we did not expect was the enormous critical and commercial success of the completed album! Very gratifying.

RA: I would imagine it is less expensive to release original soundtracks as you did with the disc, CURSE OF THAT CAT PEOPLE, devoted to Roy Webb. Do many of the soundtracks from the 1960s and before exist and are they available to you?

DW: It is possible to licence original soundtrack material either from film companies themselves or from other record companies who maintain the rights in certain soundtrack scores. Some releases or re-releases are inhibited by high royalty rates, but often the reason certain vintage scores do not make it to record is because the owners of the recordings are just not interested in licensing them. Other soundtracks are subject to (prohibitive) re-use fees due to the musicians involved before a "secondary" use can be made of the recordings - the players having only been paid for the use of the music on film, a record album representing a secondary use for which they receive additional payment. I have been able to licence many titles from both film and record companies - including A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, THE PRIDE AND THE PASSION, ROMEO AND JULIET, MYSTERIOUS ISLAND, THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY and SOME CAME RUNNING.

RA: Your disc devoted to Roy Webb is one of my favorites. He was certainly one of the most subtle Hollywood film composers of his era. Whose ideas was it to do that disc and is there enough material to do a second volume?

DW: The idea for this disc originated with the late Christopher Palmer. Chris had befriended Roy Webb in the composer's twilight years and had campaigned to get his film music on to record - successfully recording suites from NOTORIOUS and SEVENTH VICTIM. Most of Webb's collection of acetates had been destroyed in a fire - but those few selections left were carefully transferred to open-reel tape and given to Chris - who approached me with the idea to release a compilation album. We put all the selections through the Cedar noise reduction system and with careful mastering were able to transform these fifty-year old recordings into acceptable CD material. Chris unfortunately did not live to see the finished product; his untimely death proved a great blow to the crusade for film music on record - more than any of us Chris had the ability to get music into the studio. Sadly there were only enough selections to facilitate a single seventy-five minute album.

RA: You are engaged in a series of compilation recordings for Silva using the City of Prague Philharmonic. How did this series come about?

DW: We were looking for a good recording orchestra at less cost than normally encountered in London. The idea was to increase the recording schedule considerably - from about four albums a year to ten or more - and the investment needed was considerable - so pricing was all-important. Of course recording in a foreign city involves additional forms of organization - and to keep travelling to a minimum, we hit on the idea of recording three or four albums back-to back, something we had not done before. We tend to take out a whole team - conductors, score-readers, an arranger, an engineer (with his own select microphones) etc. We soon got into the swing of recording sixteen sessions or more at one go - considerably more demanding than just recording a single album in four sessions. The orchestra basically comprises what used to be the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra - and the studio is wonderfully cavernous with a good natural acoustic. It is a pleasing place to record - and Prague itself is a wonderful city to visit.

RA: How has this orchestra responded to playing all this film music? Do the members of the orchestra ever watch the films or listen to the soundtracks before recording the music?

DW: When we first went to Prague, the Czech Republic was still emerging from years of oppression - and their cultural horizons were different, more restricted than ours. When we recorded John Williams' STAR WARS music with them, the players had never heard of the films! Equally surprising was the fact they had never encountered Bernard Herrmann's music for the shower scene from PSYCHO - the musicians found this very amusing! Also initially the orchestra was uncomfortable with music exhibiting constantly changing time signatures or jazz rhythms. Conversely, they sailed perfectly through Dimitri Tiomkin compositions on the first take - and this is music which often foxes even the most expert of British players. So in those early days more rehearsal time was needed on certain compositions. Now the orchestra is adept at even the most complex and "westernised" of music; they can also deliver an extraordinarily effective "big band" swing sound. In the last six or seven years, Silva has delivered to the orchestra the most diverse music imaginable - and this has proved an education for the players; they were always fine musicians, but had for too long been denied a really varied repertoire.

RA: Are there any plans by Silva to start making albums again in Britain using any of the UK's top notch orchestras?

DW: Silva still records with leading British orchestras, recently completing albums with The Royal Philharmonic, The Royal Philharmonic Pops and The BBC Concert Orchestra. One of Silva's recent albums, THE CULT FILES (a TV and film-themes compendium which has sold half a million copies world-wide) was recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Pops Orchestra. It should also be remembered that Silva's recording schedule is remarkably diverse; after all they have two film music labels, two jazz labels, two classical labels and a television music label. It was only two years ago that Silva had the UK's best selling classical album - this in spite of competition from EMI, Sony, BMG etc. Ten years ago Silva Screen was just two guys working out of an office so small they had to share the same desk. Today they have massive multi-story offices and their group of companies is worth ... well, a lot. The success is due to business acumen and a canny awareness of what the public wants ... and (do I flatter myself here) not a little expertise.

RA: Silva produces more compilation discs as opposed to discs which feature complete scores or very lengthy suites. Is this for economical or artistic reasons?

DW: The reasons are both commercial and artistic - and these two are not mutually exclusive. As Silva's catalogue of film and television titles started to grow, enquiries came from around the world from companies - some record concerns, some magazine publishers, some advertising companies, some TV conglomerates - who wanted to licence certain tracks. This proved a considerable avenue of income. Silva immediately sought to extend its number of recorded titles. Many requests for licensing were for particular titles not yet in the Silva catalogue - and these were recorded even though no suitable album could be found as yet to accommodate them commercially. Today, given the extent of Silva's ever-growing recorded catalogue, the company gains even more income from licensing than it does from actual record sales. Now, given this fact, if Silva has the capital to spend on a recording it is financially beneficial for them to expend that money on a series of short suites - each of which is a licensable item - rather than use all that cash just to record one extended film title, which, at the end of the day is only one licensable item. This makes commercial sense. On the artistic side it is often the case that a compact suite can better serve a score than the complete score itself. Taking the main thematic material, plus some variants, and leaving out all the repeats and "redundant" passages often inherent in a score, can result in a suite which shows off the composer's compositions to their best advantage. Of course, the ardent film music buff will probably want all of a given score - but there are many complete or substantially complete soundtracks around, so I think it is permissible for one company at least to specialise in shorter, more compact suites. And by this device, good representative suites from many neglected scores have reached the public. And the general public seems to go for compendium albums; most folks like film themes and are prepared to buy the occasional collection - but it is a rare event for the public to purchase a single soundtrack album; Titanics do not happen very often.

RA: Collectors of film music seem to be a hard bunch to please. Have you found this to be true?

DW: If they are hard to please it is because film music fans comprise many differing persuasions holding varying views on film music and how it should be presented. There are those who value vintage scores, others who are into the latest soundtracks, some who will only listen to certain select composers or particular styles of film music; then there are aficionados who will only contemplate complete and original soundtracks - whilst others prefer compilations or pristine re-recordings and so on ... and inevitably there are the few who say "why did you record THAT when you should have recorded THIS!". It is, of course, impossible to please all these differing factions all the time. Luckily there are quite a number of specialist film music labels and between them I think everyone is catered for. One of the major types of criticisms which seems to be leveled at new recordings of film music stems from the expectation that the new performance should match the original soundtrack in every way - with the precise tempi, each nuance and the exact mix of the original duplicated. Complaints are forthcoming if the re-recording fails to correspond exactly with the film performance. Of course the criticism always comes from those who have the original soundtrack - and I often wonder why they should want a precise duplication of it - after all, for their purposes such a recording would be redundant; they might just as well purchase two copies of the original soundtrack if they insist on having a duplicate. No, re-recordings are made at a different time at a differing venue with a different orchestra, conductor and sound engineer. Also, the conductor is not under the kind of pressures experienced at the original soundtrack sessions - and can allow the music "more room to breath" etc. Also, the kind of recordings I produce invariably feature specially arranged concert suites - and the dramatic structure and emphasis here is different to that of the overall score. I do work with the conductor to ensure tempi are at least in line with those on the original soundtrack - but sometimes a little leeway can result in an even better performance than that on the film sessions themselves - where the conductor is harried by the restraints of time and the exacting requirements of synchronisation. One of the odd but understandable criticisms sometimes aimed at new recordings of vintage scores is that the orchestrations do not sound correct; this stems from the fact that the original, much older recording just did not have the dynamic range or was not sufficiently well-mixed to highlight the extent of the orchestration. In the new recording people are hearing detail which has been denied them before. So new recordings are usually more faithful to the intentions of the composer - even if on first hearing they sound different to the original renditions.

RA: In the past few years, you have produced many of the best re-recordings of British film scores. How do you account for the relative dearth of recordings devoted to British film music during the 1970s and 1980s.

DW: Historically British films have been parochial - and so, by association, have their scores. American movies have always been universal - and their music has proved the same. Music, whether recorded in London, Los Angeles or Bombay is now marketed world-wide whereas the ethos used to be that releases were aimed more locally - so the emphasis has been on universal product with more parochial material losing out. My recording of Ealing film scores was rejected for release in the USA by Silva's own American label! Luckily the disc is doing well in the States on import. But things are looking up for film music in general; the classical market has changed - evolved, not least through the timely intervention of Classic FM. Classical music has become, for many, the new MOR - and by association so has the best of film music. More people are listening to classically orientated music than ever before, and there is much less resistance to the notion of film music as art; only a short while ago classical music was guarded on all fronts by a conservative elite who held film music in low regard - worse, they saw it as an affront to concert music. Well, that old guard is still there, but now under siege from Classic FM and a new breed of classical music enthusiasts not concerned with elitism.

RA: How would you compare the scores being written for British films with those being written in Hollywood during the so-called 'Golden Age?"

DW: Not the same thing at all. In Hollywood all the studios maintained their own roster of composers under contract. These people worked full time as part of the studio treadmill - often undertaking poor films, although getting good movies to score too - but they had little say in which commissions they were allotted. Most had little time, if not the inclination, to pursue separate "classical" ambitions - although there are exceptions - Miklos Rozsa immediately springs to mind; although his son, Nicholas, recently told me his father was almost always engaged in work, because if he was not scoring a film he was toiling over a concert composition. In Britain, and throughout Europe for that matter, the situation was different. There were composers who worked almost solely in film, but the names which shaped British film music - Benjamin Frankel, William Alwyn, Alan Rawsthorne, Malcolm Arnold, Richard Rodney Bennett, William Walton etc were primarily classical composers who undertook film work mostly as a means to supplement their income and as a platform for experimentation. Many of Britain's film scores have been composed by occasional visitors; Gerard Schurmann, Franz Reizenstein, Arnold Bax, John Ireland, Humphrey Searle, Buxton Orr, Walter Goehr, Lord Berners, Arthur Bliss, Carlo Martelli, Don Banks, Malcolm Williamson, John McCabe, Tristram Cary, Elizabeth Lutyens etc - all composers with considerable concert compositions to their names.

RA: Were the British studios any better than their American counterparts at preserving conductor's scores and orchestral parts?

DW: No. Just like in the USA, with either the sale of or the expansion of a studio, certain bureaucrats, in order to save space and money, consigned many scores and parts to bonfires or skips. But we should not be too harsh. These scores were written for a given film; the film was made, released, then stored on a shelf. The film - and all its components - had done the job they came into being for. The film would go on to gain new life first via a reissue, then through television showings, and more latterly on video and laserdisc - but the musical manuscripts were not needed - I mean, what for? Only now with the emergence of interest in film music have those lost scores gained in significance. Of course it should have been realised that music by Frankel or Arnold or Alwyn or whoever would have an intrinsic value, but that seems not to have happened - almost all their scores were lost. It would only have taken a telephone call to the composers concerned to come and collect their music to have preserved this heritage - but it seems nobody was imaginative enough to do this.

RA: Which composers do you think made the greatest contribution to film scoring in Britain?

DW: Music for British films has always been extraordinarily diverse and adventurous. In the main it has been neo-classical in idiom but there has also been a prevalent canon of atonal and other modernistic styles. This has happened because so many contributed so much in so many differing ways. It would be difficult to light on just a select few - but the dominant composers seem to have been, by virtue of the number of scores they composed, William Alwyn, Benjamin Frankel, Malcolm Arnold, John Addison and Richard Rodney Bennett. Other composers were influential in certain genres - one thinks of James Bernard and Elizabeth Lutyens dominating horror whilst Richard Addinsell was the king of romantic melodrama. A special mention should be made of both Brian Easdale and Allan Gray who collaborated on the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger to extraordinary effect. Other composers who should be mentioned are Ron Goodwin, Laurie Johnson, Phillip Green, Clifton Parker, Lambert Williamson, Mischa Spoliansky, John Greenwood, Ron Grainer, Arthur Benjamin, Larry Adler, Robert Farnon, Matyas Seiber, Anthony Collins, Stanley Black (yes, he composed about thirty original scores) and Bruce Montgomery. It should also be remembered that Miklos Rozsa made a considerable impact on music for British films before he decamped to Hollywood. Of course, recent years have welcomed many new talents to the realm of scoring British films.

RA: Film scoring in England attracted the very best British composers during the 1940s and 1950s. Is the same true today?

DW: Time will tell. When Malcolm Arnold was first working on films, he had yet to establish his classical reputation - and at the time of Walton's first brush with the Cinema, he had only just made a name for himself. Benjamin Frankel wrote the majority of his classical compositions only after many film commissions - and Richard Rodney Bennet was just twenty-one when he composed for his first film. We can look back now and say ... ah, the great William Walton scored films ... but he was not the beloved Establishment figure he was to become when he initially composed for the Cinema. There are considerable musical talents working within film today - and we shall have to leap ahead many years to genuinely appraise whether the standards set by Alwyn et al are still being maintained - but I suspect the same opportunities are not there today. In the old days many films were made inexpensively and producers were willing to take a chance on this composer or that; now, with production costs escalating, producers are hedging their bets by only employing composers with "a track record" (sic) and fewer talents are gaining access to film scoring. Worse, proven composers are having their work rejected as being "unsuitable" by young film executives with little working knowledge of either films or music; I was recently music director on the film "The Gambler" - with Sir Michael Gambon as Dostoyesvsky - but Gerard Schurmann's score, which everyone on the film agreed was extraordinarily effective, was vetoed by the distribution company as unsuitable, with little of Gerard's music left in the film as released.

RA: I understand you personally financed the disc devoted to Sir Arnold

Bax's OLIVER TWIST and MALTA GC. Is OLIVER TWIST a favourite score of yours?

RA: I understand you personally financed the disc devoted to Sir Arnold

Bax's OLIVER TWIST and MALTA GC. Is OLIVER TWIST a favourite score of yours?

DW: This score was really my introduction to Bax. I had gained the 78s of the recorded suite quite early on; later I saw and loved the film. Having the finances to make my first recording, I decided to produce a compendium of classic British scores - and wanted to include the suite for OLIVER TWIST. The publishers, Warner-Chappell were happy to let me have the scores and parts - but by chance Graham Parlett, a Bax aficionado, was at that moment going back to the original score and extending the suite considerably. Did I want to record all these selections? Well, yes. Then the publishers suggested I might like to look at Bax's score for the wartime documentary MALTA G.C. Another record company had expressed interest in this but upon seeing the sorry state of the score - poorly copied to microfilm from the original held in Malta - declined to proceed. I showed the manuscript to conductor Kenneth Alwyn - who was keen to record the work - and felt confident enough to restore the score to legibility, which he duly did. Two excerpts had been recorded from the score in the days of 78's - and a fairly recent recording had been made of the finale - a rousing march, but that was all. The BBC had maintained a complete performance recorded for radio during the war - and kindly allowed me access to get a feel for the desired tempi etc. The Imperial War Museum also made the original film available for Kenneth Alwyn and I to view on a Moviola, giving us the freedom to run back and forth over the print and truly assess the music.

RA: Did the Bax disc sell well?

DW: Yes. I was fairly confident that it would thanks to the recent success of Chandos Records' spate of marvelous recordings of Bax concert works; Bax was in vogue. In fact the initial demand from British shops was surprising - more than I would have hoped for. I later licenced the disc to ASV Records along with a recording I had made of Malcolm Arnold's The Sound Barrier Rhapsody; I think they also did quite well with the recording.

RA: Have you personally financed any of the other discs you've produced?

DW: Luckily all my subsequent recordings have been financed by other

concerns; but I have a wish-list of dozens of British film scores I should

like to commit to record - but there is never sufficient finance to realise

everything.

RA: I understand your superb disc devoted to THE RED SHOES and Vaughan Williams' COSTAL COMMAND has yet to break even. This disc was extremely well played and produced and received excellent reviews. All the ingredients for a "hit" are there. Why do you think it failed to make money?

DW: I think it has made its money back now. I do not know why the public response was lukewarm. Here we had a perennial favourite - THE RED SHOES BALLET - plus premiere performances of works by Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss and Gerard Schurmann. I had wrongly assumed that anyone interested in Twentieth Century British music would want this disc. It remains the record I am most proud of. Thankfully, it is still in catalogue both here and in the United States so it can still be purchased by anyone who might be interested.

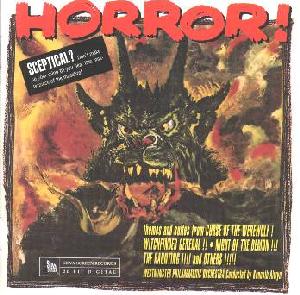

RA: One of your most successful compilations was the disc entitled

"Horror!" which included suites from many British horror film scores including

Frankel's CURSE OF THE WEREWOLF and Clifton Parker's NIGHT OF THE DEMON.

Were you surprised by the success of this disc?

DW: Not really. Horror usually sells. Besides film music buffs, you are also appealing to a massive coterie of horror fanatics - people who will purchase anything connected with their favoured genre - and then there are those who think a "horror" compilation might be "fun." Silva had previously done very well with a compendium of scores from Hammer Films - led by James Bernard's evocative music for DRACULA - and in essence the HORROR album was an extension of this - although the repertoire here was more adventurous. I have to say though that my reasons for mounting the album had little to do with the horror genre itself - although I am very fond of those kind of movies, certainly as they were in the Fifties and Sixties; I was really aiming the recording over the heads of the expected audience and hoping to snare some "classical" interest as well. Forget the lurid film titles for a moment and just consider the composers concerned: Benjamin Frankel, Gerard Schurmann, Humphrey Searle, Carlo Martelli, Buxton Orr - now that's an elite classical line-up.

RA: The "Horror!" disc whetted my appetite for more music from those films not to mention more scores by Frankel, Searle and Parker. Any chance of a follow up album or discs devoted to the complete scores for NIGHT OF THE DEMON or CURSE OF THE WEREWOLF?

DW: I still have a batch of "horror" scores and parts yet to record - so a second volume will inevitably appear. I don't think single albums of CURSE OF THE WEREWOLF or NIGHT OF THE DEMON would attract sufficient sales to justify complete recordings - but it would be possible, if the original tapes or acetates were available, to issue the complete original soundtracks of such scores. I did release, on my Cloud Nine label - and with Hammer's blessing, Tristram Cary's complete score for QUATERMASS AND THE PIT - and I hope to also release his complete music for BLOOD FROM THE MUMMY'S TOMB.

RA: How do you choose which scores to record?

DW: Oh dear! A mixture of elements; two parts personal taste and favourites, one part excellence of material; add a huge helping of commercial viability. Then comes the hard part - convincing whatever management is involved to invest their money in your hair-brained project! These days, particularly at Silva, albums projects are usually realised in terms of their commercial prospects - and this is usually done via committee; the more expert people who offer an opinion the better. This seems to work well - as in the past few years Silva albums have tended to sell well around the world - and, of course, individual tracks bring in excellent licensing revenue. Happily, it is entirely possible to insert the occasional esoteric item in amongst the more commercial titles - and as proved by the HORROR album, it is also possible to mount an entire album of unusual repertoire and still generate good profits.

RA: Are there any scores you would like to record but can't due to copyright problems or unavailability of parts?

DW: It seldom happens that you cannot get to record a particular score. As I said earlier. If a score does not exist, then it is a matter of reconstructing it. It has sometimes happened that we cannot get "first recording rights" on a particular score - as a recording would run contrary to whatever plans the music's publisher or the film company have for the music. I can recall being refused permission to record both Dimitri Tiomkin's I CONFESS and Maurice Jarre's FIREFOX. On other occasions we have just had to wait until such permission was forthcoming - an example being Dee Baron's music for HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER which we had to apply three times for.

RA: Do you have any favorites among the many discs you've produced?

DW: As I said before, THE RED SHOES is a firm favourite - also my Bax recordings. I am fond of my recording of Miklos Rozsa suites - which premiered his music for BEAU BRUMMELL, which, of course, on the film was credited to Richard Addinsell, although, in fact, Addinsell had only contributed a love theme and a set of period dances. Also this album marked the first time I had the opportunity to work with a substantial choir, The Crouch End Festival Chorus, who blossomed for the selections from QUO VADIS and KING OF KINGS. In the three years since then James Fitzpatrick and I have had the opportunity to record no less than sixty pieces for orchestra and choir; working with the Crouch End Festival Chorus has become a regular - and pleasurable experience. I must also mention again the HORROR album, which I regularly play. Perhaps my criteria for choosing which scores to record is really a desire to have those albums at home in my own collection!

RA: Why are there so few CDs devoted to complete scores from British films? Contrast the Hollywood film scores - whole CDs given over to a single film's score.

DW: I think the answer lies in the parochial nature of British films. American films first of all are addressing a vast continent - then the world - with untold millions of potential soundtrack buyers - whilst we are a small island nation with a relatively restricted home market and a modest overseas market. When the soundtrack to THE FULL MONTY was released, the record company concerned probably did not expect to make much profit - and I understand they picked up the album after a number of other companies had turned it down; the enormous success of the film resulted in considerable album sales - but unfortunately this does not happen very often with soundtracks for British films. It is not fair to compare the market for American soundtracks with that for British soundtracks - and this is also true for French, Spanish, Dutch soundtracks etc. The standard Hollywood film now costs in excess of fifty million dollars - and can cost many times that - whereas a standard British movie comes in at about three or four million dollars. We are talking very different ball-parks here.

RA: A number of universities in the states have archives for film music and make of it an academic subject - are there any similar institutions in the UK and do you have any formal relationship or contact with them.

DW: I have not done my homework on this but I think there are few British institutions which keep such archives. I know that one University looks after the works of Alan Rawsthorne but that is all I can think of offhand.

RA: What happens to film score materials after you have finished with them?

DW: Most of the materials we reconstruct have an official publisher - whilst other scores remain the copyright of the relevant composer or their estate. So the situation is that either a publisher or composer "owns" the copyright in the score; however, they do not have either score or parts - we do, and as we have reconstructed them, they remain our property - although not our "intellectual" property. Therefore a deal is struck whereby the score and parts are placed with the relevant publisher or with the publisher of a composer's choice. The publisher is empowered to hire the materials out for concert performance anywhere in the world (although recordings are not sanctioned) - and income generated is shared by all parties concerned. This means that an extraordinary number of suites drawn from classic film scores are constantly coming on to the concert market. Unfortunately there are still few film music concerts staged in Britain - but hopefully one day a sea-change will see us enjoying as many such concerts as they do in the USA. But the important fact is that these scores - once lost - are again a tangible part of our heritage.

RA: Can you give us a sneak preview of the scores you plan to record in the near future?

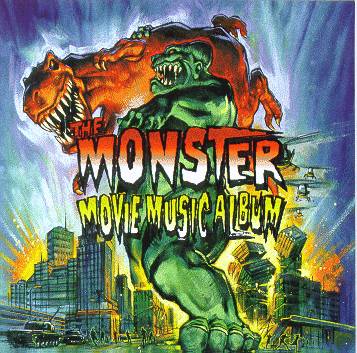

DW:

Even in the cloistered world of film music secrecy about forthcoming

projects is advisable. However there are just about to be released some

recordings in which I have had a hand: a seventy-five minute album of "monster"

music which includes s substantial suite from Japanese Godzilla movies, plus

music from the 1933 KING KONG (Max Steiner), the 1978 remake (John Barry),

and KING KONG LIVES (John Scott). The album also features suites by Mario

Nascimbene for ONE MILLION YEARS B.C., WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH and

CREATURES THE WORLD FORGOT. Bringing up the rear are a substantial suite

from Jerry Goldsmith's score for BABY (about an infant dinosaur), the premiere

recording of Robert Folk's THEODORE REX, James Horner's music for two animated

features THE LAND BEFORE TIME and WE'RE BACK - and a rollicking version of

THE FLINTSTONES just for fun - oh, and a MYSTERIOUS ISLAND suite which includes

The Giant Bee and Giant Crab sequences. Then there will be albums of Continental

Film Classics - LAST TANGO IN PARIS etc - and an album of suites from disaster

movies - THE SWARM, TITANIC, THE TOWERING INFERNO etc., and a second volume

of CINEMA CHORAL CLASSICS.

DW:

Even in the cloistered world of film music secrecy about forthcoming

projects is advisable. However there are just about to be released some

recordings in which I have had a hand: a seventy-five minute album of "monster"

music which includes s substantial suite from Japanese Godzilla movies, plus

music from the 1933 KING KONG (Max Steiner), the 1978 remake (John Barry),

and KING KONG LIVES (John Scott). The album also features suites by Mario

Nascimbene for ONE MILLION YEARS B.C., WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH and

CREATURES THE WORLD FORGOT. Bringing up the rear are a substantial suite

from Jerry Goldsmith's score for BABY (about an infant dinosaur), the premiere

recording of Robert Folk's THEODORE REX, James Horner's music for two animated

features THE LAND BEFORE TIME and WE'RE BACK - and a rollicking version of

THE FLINTSTONES just for fun - oh, and a MYSTERIOUS ISLAND suite which includes

The Giant Bee and Giant Crab sequences. Then there will be albums of Continental

Film Classics - LAST TANGO IN PARIS etc - and an album of suites from disaster

movies - THE SWARM, TITANIC, THE TOWERING INFERNO etc., and a second volume

of CINEMA CHORAL CLASSICS.

RA: What are your Desert Island Film Scores? You can pick as many as you like.

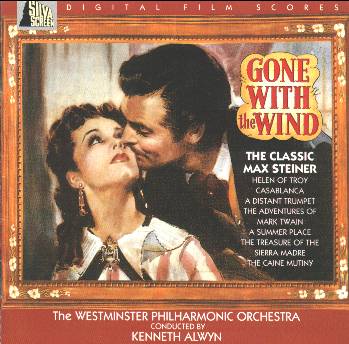

DW:

I am bound to leave out some wonderful scores but here goes: CLEOPATRA

(Alex North), PLANET OF THE APES (Jerry Goldsmith), FOREVER AMBER (David

Raksin), DUEL IN THE SUN (Dimitri Tiomkin), LAND OF THE PHARAOHS (Dimitri

Tiomkin), GONE WITH THE WIND (Max Steiner), MOBY DICK (Philip Sainton), OLIVER

TWIST (Arnold Bax), BATTLE OF THE BULGE (Benjamin Frankel), DEATH OF A SALESMAN

(Alex North), THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (Miklos Rozsa), EL CID (Miklos Rozsa),

DANCES WITH WOLVES (John Barry), THE THREE WORLDS OF GULLIVER (Bernard Herrmann),

THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (Erich Wolfgang Korngold), ITS A MAD WORLD (Ernest

Gold), THE PRIDE AND THE PASSION (George Antheil), TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

(Elmer Bernstein), TARAS BULBA (Franz Waxman), HOW THE WEST WAS WON (Alfred

Newman), ALEXANDER NEVSKY (Sergei Prokofiev), THE OVERLANDERS (John Ireland),

THINGS TO COME (Arthur Bliss), PASSPORT TO PIMLICO (Georges Auric), BENEATH

THE TWELVE MILE REEF (Bernard Herrmann), MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (Bronislau

Kaper), ODD MAN OUT (William Alwyn), THE LONG ARM (Gerard Schurmann), THE

FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE (Dimitri Tiomkin), THE RED SHOES (Brian Easdale),

THE AFRICAN QUEEN (Allan Gray), HENRY V (William Walton), HENRY V (Patrick

Doyle) .... I could go on and on. I note I have chosen mostly expansive old-style

scores - and nothing from recent films! I guess I am just an old romantic

at heart!

DW:

I am bound to leave out some wonderful scores but here goes: CLEOPATRA

(Alex North), PLANET OF THE APES (Jerry Goldsmith), FOREVER AMBER (David

Raksin), DUEL IN THE SUN (Dimitri Tiomkin), LAND OF THE PHARAOHS (Dimitri

Tiomkin), GONE WITH THE WIND (Max Steiner), MOBY DICK (Philip Sainton), OLIVER

TWIST (Arnold Bax), BATTLE OF THE BULGE (Benjamin Frankel), DEATH OF A SALESMAN

(Alex North), THE THIEF OF BAGDAD (Miklos Rozsa), EL CID (Miklos Rozsa),

DANCES WITH WOLVES (John Barry), THE THREE WORLDS OF GULLIVER (Bernard Herrmann),

THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (Erich Wolfgang Korngold), ITS A MAD WORLD (Ernest

Gold), THE PRIDE AND THE PASSION (George Antheil), TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

(Elmer Bernstein), TARAS BULBA (Franz Waxman), HOW THE WEST WAS WON (Alfred

Newman), ALEXANDER NEVSKY (Sergei Prokofiev), THE OVERLANDERS (John Ireland),

THINGS TO COME (Arthur Bliss), PASSPORT TO PIMLICO (Georges Auric), BENEATH

THE TWELVE MILE REEF (Bernard Herrmann), MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (Bronislau

Kaper), ODD MAN OUT (William Alwyn), THE LONG ARM (Gerard Schurmann), THE

FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE (Dimitri Tiomkin), THE RED SHOES (Brian Easdale),

THE AFRICAN QUEEN (Allan Gray), HENRY V (William Walton), HENRY V (Patrick

Doyle) .... I could go on and on. I note I have chosen mostly expansive old-style

scores - and nothing from recent films! I guess I am just an old romantic

at heart!

|

|

June1998

Return to Film Music Main page