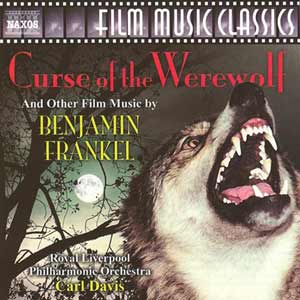

Curse of the Werewolf

Music composed by Benjamin Frankel

Also features music from So Long At The Fair [6:21], The Net - Love Theme [3:05], and The Prisoner [30:35]

Performed by Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra

Conducted by Carl Davis

Available on Naxos Film Music Classics (8.557850)

Running Time: 74:40

Crotchet Amazon UK Amazon US

London-born Benjamin Frankel scored over 100 films including The Seventh Veil, The Importance of Being Earnest, Night of the Iguana and Battle of the Bulge (nominated for Best Original Score at the 1966 Golden Globes). During the 1930s and 1940s he was also busy in the musical theatre, as musical director and arranger working for such famous names as C.B. Cochran and Noel Coward.

Frankel’s Werewolf (1959) music is some distance removed from the conventional Hollywood horror score. It is more imaginative, has more depth and characterisation. Its wildness, screaming horror and garish colouring are summed up in the ‘Prelude’; its hammering ostinato a tongue-in-cheek play on the Hammer studio nomenclature? A fear-simulated, teeth-chattering opens a calmer cue ‘The Beggar’ which is a very close relative of Frankel’s So Long at the Fair music. ‘Servant Girl and Beggar’ is a conversation piece before cruelty overtakes pathos as the servant girl is raped by the crazed beggar and becomes pregnant with Leon (Oliver Reed) who will be cursed and afflicted with lycanthropy causing him to change into a werewolf at each full moon. ‘Baptism’ is full of foreboding and things that screech and flutter eerily, contrasted with measures of pathos suggesting Leon’s essential loneliness. ‘Pastoral’ is just that -Beethoven-like countryside serenity. The rest of this 34-minute, 12-movement suite from the 1959 film contrasts these pastoral and pathos elements with tense and savage music as Leon’s encounters away from his kindly foster parents lead to the inevitable trail of carnage. My colleague, Rob Barnett, in his review for MusicWeb, has rightly suggested that Frankel’s music reminds him of Cesar Franck’s Le Chasseur Maudit. Indeed the six-minute ‘Finale’ vividly suggests the hunting down and eventual slaying of the wolf-man with the obligatory silver bullet and the music, besides that of Franck also echoes Vaughan Williams, Benjamin Britten and Bernard Herrmann. A most exciting cue.

So Long at the Fair (1950) concerned a brother and sister (David Tomlinson and Jean Simmons) who travelled to Paris for the great 1889 Exposition. Consternation follows when the brother disappears mysteriously. The six-minute suite includes besides the celebrated ‘Carriage and Pair’ music, that became a much-requested light music favourite, sentimental music and breezy sea voyage (across the channel) that captures the essence of the period. The Net (1953) was about a team of scientists working on experimental aircraft at a top secret installation. Frankel’s beautiful love music scored for piano and orchestra adds a note of tenderness in a tense drama.

The Prisoner (1955) starred Alec Guiness as Roman Catholic priest arrested and interrogated (by Jack Hawkins) and ultimately brain washed into confessing in a show trial before the world’s media. This score is bleak and pessimistic, the music poignant and sympathetic to the priest’s plight but with with cruel crushing measures signalling the intolerance of the regime (shades of Shostakovich) and despairing bell tolls.

Carl Davis leads the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in committed performances of some fine British film music of the 1950s.

Ian Lace

Rating:

4

Return to Reviews Index