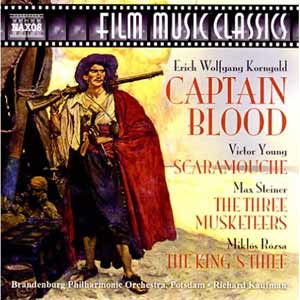

Captain Blood and Other Swashbucklers

Music composed by Miklos Rozsa, Victor Young, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Max Steiner

Music performed by the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra

Conducted by Richard Kaufman

Suites arranged\reconstructed by Christopher Palmer, William Stromberg, and John Morgan

Produced by Klaus Bischke

Available on Naxos (8.557704)

Running Time: 65:05

Crotchet Amazon UK

See also:

Captain Blood (previous release of this recording) After the film medium had been introduced to the possibilities of sound in the late 1920s, the so-called “golden age” of American film scoring would soon begin. It was first and foremost through the musical gifts of European immigrants such as Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold that the fundamental principles of film music were established, their craft being deeply rooted in the great traditions of 19th century Viennese opera.

Yet after a few decades featuring many fine masterpieces, the golden age of film music began to fade towards the late 1950s after the strong grip the commercial film industry had had on the American moviegoers over a long period of time inevitably resulted in one huge musical anachronism. For this reason along with the competition from television, the music departments suffered either the sacking of many employees or were closed down entirely. Orchestral scores began to play a smaller part in a film’s narrative, whilst the use of popular music would become the fresh trend of a Hollywood trying to change. Eventually it was the entire Hollywood way of thinking that needed to be changed; the flawed aesthetics of the somewhat monotonous studio system were gradually dissolved and the likes of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg would come to reshape the art of film making and help establish a brand new era.

Starting in the 1990s, long after the decline of the golden age, Naxos began an ongoing effort to reconstruct and record brand new suites from many of the better scores of the golden age, bringing the glamorous and enthusiastic atmosphere of the period to a younger generation of music fans. Their Film Music Classics series is a priceless gift to lovers of film music that offers brand new interpretations of stunning achievements such as Steiner’s landmark King Kong score or Shostakovich’s Hamlet. This new disc entitled Captain Blood and other Swashbucklers is a re-issue featuring reconstructed suites from The King’s Thief, Scaramouche, Captain Blood, and The Three Musketeers. All the music is performed by the Brandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra and conducted by Richard Kaufman, assisted by the acoustics of the Jesus Christ Church in Berlin, Germany.

Christopher Palmer is credited for having prepared the single movement suite from Miklos Rozsa’s The King’s Thief (1955). Apart from the rousing overture with a gorgeous main theme, the suite feels like the awkward crossing of a roughly sketched first draft and a “cut and paste” job. The second theme introduced after the overture is so similar to the theme from the third movement of Mozart’s piano concerto no 17 in G major, that a comparison is almost unavoidable. Because where Mozart blesses us with luxurious counterpoint and elements of spontaneous surprise, Rozsa is far too repetitious with his material and frankly quite lazy. The performance is certainly very energetic and more than adequate, but it helps little when the score remains more or less eventless and offers so little to work with both in terms of dynamics and variation. I find it hard to believe that Rozsa, the composer of Spellbound and Ben Hur, would compose such incoherent mess. Perhaps Palmer’s reconstruction did not do the composer’s score justice?

Victor Young’s music for Scaramouche, a film set during the French revolution, is apart from the adventurous overture remarkably modest, and I mean that in a good way. Like a collection of fun dance episodes, the music progresses from one light hearted, festive episode to another. Seldom does it turn back to recapitulate, and seldom does any form of complexity overshadow the pure bliss of melodic simplicity. Somewhere in there we hear a brief quote from the French national anthem and unexpectedly, the theme from Shostakovich’s Leningrad symphony is reshaped to a happy and straightforward dance! What we have here is just plain and simple symphonic fun, and you can hear how much fun Kaufman and his orchestra were having with Scaramouche. It’s a great suite with many fine moments.

But at the end of the day, the suite from Korngold’s Captain Blood is by far the most outstanding contribution to this album – both in terms of performance and composition. This is the music that practically invented the Swashbuckler genre, and Korngold’s complete command of harmony, form, melody, and counterpoint ranks this score up among the great masterpieces of film music. The way that the overture drags the listener into the exciting universe of heroes and villains, adventures and romance, is to say the least – stunning.

Unlike the suite from The King’s Thief, Captain Blood treats us to the element of surprise, with exciting dynamic transitions, melodic creativity, and variation. In other words the entire spectrum of the orchestra’s range of expression is presented! All credit to the musicians of the Brandenburg philharmonic for giving us a solid performance of a very difficult and musically very challenging score.

Closing the album is Max Steiner’s The Three Musketeers which is, like Young’s Scaramouche, also set in France. The basic element of the score is the lovely love theme, only a few notes long and yet instantly recognizable. As the suite progresses, all Steiner needs to do is suggest two or three notes and we immediately know where they come from! Once again Steiner’s love of the leitmotif resulted in an intriguingly clever musical trigger that I’m sure enhances the film’s emotions drastically. However, it is unfortunate how the narrow simplicity of the theme and arrangement prevent the music from being all that interesting; eventually the number of quotes begins to halt the progression of the suite. Apart from the love theme, the music mainly consists of some very pompous march music that, although brilliantly orchestrated, eventually begins to wear off its effect just as the love theme does.

So the music from both The King’s Thief and The Three Musketeers fails to impress, and the question is whether it is unethical to compile these concert suites from film scores when the material so obviously wasn’t intended to serve this purpose. In the case of Korngold, we know that he would approach the art of film composition as he would a concert hall project. But Steiner and Rozsa were of a different state of mind and these suites should prove it.

For Victor Young’s Scaramouche and a quality performance of Korngold’s Captain Blood this album is certainly worth checking out for dedicated fans of the golden age. However, the Rozsa and Steiner contributions I could do without.

Mark Rayen Candasamy

Rating:

3

Return to Reviews Index