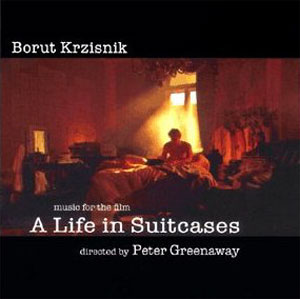

A Life in Suitcases

Music composed and produced by Borut Krziznik

‘Love Song No. 1’ and ‘Miracle on Magatrea’ from Stories from Magatrea

Virtual orchestra performed by Borut Krzisnik

Available on Mellowdrama Records / First Name Soundtracks (NAME-403)

Running Time: 69:01

Available for purchase from Mellowdrama Records

See also:

...the composer’s website, ...and this review of his concept album Stories from Magatrea . “It is astonishing with what finality theoreticians and artists of a certain historical era or an art movement negated and discredited earlier movements and marked out their position as the only true and final one. Looking back at the multitude of artistic movements they all seem to have the same historical relevance to me, and I certainly do not find any contemporary movement superior just because I happen to live in this time, in the short span of years when such movements dominate the cultural landscape.”

This quote comes from Slovenian composer, guitarist and pianist Borut Krzisnik, who replaces Michael Nyman as director Peter Greenaway’s partner-in-crime for this unusual film about the biographical qualities of the suitcases belonging to a fictional man called Tulse Luper. Since parting ways with Nyman after Prospero’s Book (whether amicably or not is unknown), Greenaway’s films have lost the consistent musical direction the unwilling minimalist lent them – there’s little internal or inter-film continuity to the musical landscapes of The Baby of Macon, The Pillow Book or 8 ½ Women. (Mind you, the film’s themselves barely hang together on the strength of the ideas, though I must confess I’ve always been squeamish with Greenaway’s fixation on living and dead anatomy.)

Back to Borut Krzisnik… whose original score for the film dominates this new joint release from First Name and Mellowdrama Records. (There are two pieces included from one of Krzisnik’s concept albums – Stories from Magatrea – doubtless the material that got him the job.) I include the quote above because it’s as strong an insight as I can point to regarding the nature of his music. His music can’t be pigeon-holed. He’s not a minimalist. He’s not a romantic. He’s not a post-modernist, or a baroque composer, a Slovenian folk improviser, a student of Stravinsky… he’s all these things. He’s not kidding when he says he regards all previous artistic movements as having equal weight! His music is so utterly full of … just about everything. The glissandos of virtual orchestra that draw us into to the solo violin exploration of the epic opener ‘Trembling Web’ could be described as minimalist… but not in any way that would make you think of Glass, Riley, Reich or Adams. Syncopated interludes give way to a haphazard landscape that had me thinking of the ‘Rite of Spring’. The contrapuntal writing in both synthetic and real instruments in this and the following tracks point us back to Bach, but only in technique – the sound Krzisnik explores here feels as fresh as anything. And there’re hints of a more post-modern perspective: this is music created largely at the mixing stage – electronic manipulation of (individual instrument and entire ensemble) playback speed, timbre, brief intrusions of complete silence, and other devices draw attention to the music itself as a product of technology.

‘Trembling Web’ is the highlight – but there are many other sections of interest. It’s a hard score to analyse using the class terms of film music analysis – themes, signatures, genre references, and such –because each piece is an independent musical journey with similar fundamentals to the whole, but distinguishing characteristics. ‘Festa’ pounds on insistent rhythms and complex harmonic accompaniment to a melody that feels like the ghost of folk idea. ‘Love Song No 1’ is a rare slower movement: a strange two-voice song filled with avante-garde effects. The same effects open ‘Sudden Spell’, which works up a furious pace a la gypsy folk songs. The epic ‘March to Eternity’ follows – an extended exploration of Krzisnik’s string writing – bound to leave the listener hypnotised and breathless by its end. Rounding out the program is ‘Slaves’ - Krzisnik’s re-interpretation of the haunting melody from Verdi’s Nabucco, re-arranged so that one is struck by both the beauty of the melody and the perversity of its interpretation here. Wth the exception of rare acoustic solo interludes, all styles pass through the filter of a ‘virtual orchestra’, an ensemble whose performance is credited to the composer himself, but explained in Mellowdrama’s press release as “the sound of a real orchestra in the digital domain”, whatever that means.

We often hear calls for innovative film music. I don’t know how long the composer has been doing this sort of thing over his four previous solo albums, but I’d say this is about the closest thing to it this year. This material is so outside of conventions that I wouldn’t be surprised if, much like Greenaway’s former collaborator Michael Nyman, the film was edited to the music rather than the other way around. I doubt Borut Krzisnik will ever break into conventional film music circles without lobotomizing his eclectic aesthetic impulses, nor should he – he seems to have found something fresh, why not explore it? Whatever his future in film scoring, we can only be thankful to the composer for presenting one of the most distinctive film scores in a long time. Which is not to say it’s the most enjoyable thing I’ve heard this year, but then you don’t listen to this sort of thing because its guaranteed to push your buttons; you listen to this sort of thing because it will arrest and amaze you.

Production values are typically strong from Mellowdrama Records (though First Name Soundtracks seems to be the dominant entity here in production). The sleeve notes are frustratingly vague, well-appointed, and present more intriguing imagery in sixteen pages than you’ll find in the average Hollywood feature film. If there’s anything to complain about, it’s that the liner notes miss Glen Aitken’s studious touch from Mellowdrama’s previous releases. The music lacks a dramatic context that the remarks here by Greenaway and Guido Sprenger certainly don’t supply. Even a little more information on the production of the music wouldn’t hurt. Otherwise an unlikely must-have album.

Michael McLennan

Rating:

4.5

Return to Reviews Index