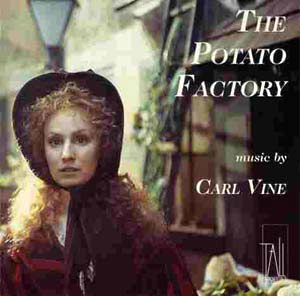

The Potato Factory

Music composed, orchestrated and conducted Carl Vine

Performed by The Tall Poppies Orchestra

Produced by Christo Curtis

Available on Tall Poppies (TP148)

Running Time: 48:06

See Tall Poppies to purchase, or go to Carl Vine’s website, see ‘The Potato Factory’ under the ‘CDs’ section.

See also:

You Can’t Push the River Complete Symphonies With six symphonies, a seventh on the way, seven concerti, works in just about every aspect of chamber music, and over twenty dance scores under his belt, it’s a worthwhile question as to whether there’s any musical genre Australian composer Carl Vine can’t turn his hand to. Whatever it is, it isn’t the film score, for his occasional forays into the medium as composer (The Battlers, beDevil, You Can’t Push the River, this score) and conductor/orchestrator (for Nigel Westlake on Babe) combine a keen dramatic sense with his distinct and ever-evolving musical voice.

Accompanying a four-hour miniseries adaptation of Bryce Courtenay’s novel of the same name, The Potato Factory (2000) told of Australia’s foundational years through the eyes of common criminals transported from the streets of London to the colonies, the criminals including Ikey Solomon (Ben Cross), his wife Hannah (Sonia Todd), and his mistress/partner-in-crime Mary Abacus (Lisa McCune). Of all his work for film, the score is probably the one that draws the most on Vine’s bold symphonic style. The main theme is very much the bold romantic cinematic theme the makers of the show desired to accompany their epic tale, and is presented in numerous variations in ‘Streets of London’, first maestoso with brass melody, and churning string harmonies; then softer in the woodwinds, flitting across pizzicati; interrupted by a regal idea before resuming in the strings; then for flute, and again for full orchestra. It’s a fine theme in all its variations – worthy of Golden Age scoring, though in the particulars quite unlike any theme I’ve heard from that period. Thankfully the theme, which is used to suggest both hope and achievement in the film, isn’t overused – returning for full orchestra at the midpoint (‘Transportation to the Colonies’), for solo violin and strings (‘Mary and Ikey’), and for the majestic conclusion (‘Reunited’).

The nice thing about this score is that every cue is essentially distinct from all others – coming with new ideas, or new approaches to ideas presented earlier. This is not to say that there aren’t structuring ideas besides the main theme – there are, for both Ikey and Mary. But those melodies are so subtly woven into each cue that they only open up to the attentive ear on closer examination. Mary’s theme opens ‘Young Love Goes Wrong’, which moves from winsome pastoral beauty and optimistic young love (celebratory horn and string writing) to betrayal (dark bassoon and low string rumblings) before a sadder reading for oboe. The grainy virtuoso violin idea returns in ‘Mary’s First Job’, an orchestral assault that leaves Mary’s theme listing in the oboe.

The composer relates that finding a consistent theme for Mary was a struggle, as her personality changes so much over the course of the four hours of the miniseries. Accordingly there’s a great deal of variety to her musical arc – not simply resting on the one musical idea of a vulnerable young woman. Soft harp and string tremolos begin ‘Mary’s Hands’, a sombre bassoon introducing dissonances in the violins and a martial trumpet line. The close of that cue features Alexandre Oguey’s cor anglais in plaintive lament. As oppressive is the sinuous violin idea that ‘Mary’s First Job’, the cue developing into a variation of Mary’s theme for ‘hardship’ that recurs in the penultimate track ‘Ikey’s Safe’. More optimistic is the aspiring theme in clarinet (doubled with oboe) that begins ‘Egyptian Mary’, with a quotation from a period string quartet (Hayden, I think) characterising English gentry. The horn-led theme halfway through this cue is particularly warm. Mary’s theme re-emerges for horn and oboe soloists towards the end of ‘Ikey’s Safe’ – now more stable harmonically to give closure to Mary’s journey.

There are probably three cues I’m most drawn to in the score. The more playful ‘Ikey’s Shopped’ is a brilliant piece of character scoring, with its heavy-light question-answer pattern for brass and woodwind over strident string rhythm introducing the main theme for Ikey. (Elements of which later appear in ‘Ikey Escapes’ and ‘Hannah the Viper’.) ‘Transporation’ is another strong work, moving from the composer’s elegant main theme to a haunting cor anglais melody that appears more than once throughout the third act of the story. As proof that love is possibly the most fruitful subject for film composers to wax on, ‘Ikey and Mary’ is another fine track. Solo violin leads into a string reprise of the main theme in ‘Ikey and Mary’ before brass object to the couple’s passion, the violin later introducing a jubilant new theme, and a gentle reading of the main theme for solo violin, horn and woodwinds.

And so the score goes, Vine’s skilful orchestrations never over-complicating the emotional implications of the music, nor simply rely on basic theme-and-variations ideas to tell the story musically. What will be of most interest to film score collectors here is the manifold evidence of a gifted composer for orchestra turning his hand to a period epic tapestry – a combination that has provided so many fine film scores in the past, and does so again here. One wishes based on the evidence here that it was Carl Vine whose door producers were knocking on every time a new Dickens adaptation or period epic appears, and not always Rachel Portman or Stephen Warbeck. (Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with their scores, this just feels like another level.) To those who miss the days when film scores were written by the stronger symphonic composers of their day, The Potato Factory is a must.

Michael McLennan

Rating:

4.5

Review copy provided by the reviewer.

Return to Reviews Index