Film Review

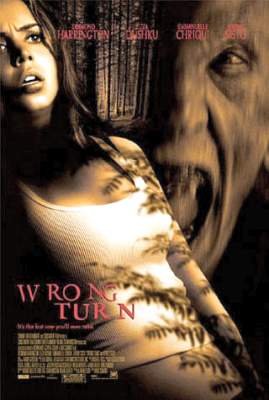

Wrong Turn

Score composed by Elia Cmiral

Written by Alan B McElroy

Directed by Roy Schmidt

Principle Cast:

Desmond Harrington

Eliza Dushku

Emmanuelle Chriqui

Jeremy Sisto

Lindy Booth

Julian Richings

Kevin Zegers

Twentieth Century Fox

Running time: 85 minutes

Certificate 18

UK Release 27th June 2003

There is a scene in Roy Schmidt’s Wrong Turn where our campers, bolted up inside a wooden tower, are given the choice of being burnt alive or jumping. They jump, and swing through the branches like miniature Tarzans. It is one scene where Schmidt had the opportunity to make something really innovative happen – something that would astound us in what is largely a routine, albeit often gripping, horror film.

But Wrong Turn, like so much of the genre over the past 20 years, is hampered by a debt to the past it cannot escape. The Hills Have Eyes and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre hang round this movie like giant millstones – especially the latter film, soon to be remade, but we can be sure, without the audacity that Tobe Hooper brought to it. And in part, what is wrong with Wrong Turn is that it lacks an in-your-face audacity. Where Hooper merely hinted at the atrocities we knew were happening Schmidt is much less subtle. Finding an ear on the ground is just a prelude to being garrotted by barbed wire; being shot through the eye with an arrow and having it exit an unbelieving copper’s head (in an admittedly dazzling display of virtuosic special effects) is just a prelude to his own decapitation with a cleaver. The violence escalates alarmingly as the film progresses, but what it achieves just beyond the bravura is minimal. It is hackneyed, and for the seasoned horror viewer simply unimaginative.

But this is by no means a bad film – in fact, at times, it is a rather good one. It is no better than when our campers, stranded in a seemingly equatorial jungle (even though this is West Virginia), stumble upon the cabin where our three grizzly, genetically deformed axe-murderers live. This cabin owes a huge debt to Texas (and also to Ed Gein): the bones hanging from the doorway, the hearts in the fridge, the severed arm in the bathroom and the general decay of rotting food and larvae crawling randomly across the place all hint at an earlier terror. What makes this scene a cut above the rest of the film, and so many others, is the tension which Schmidt builds up as we discover each room, each secret, each grisly discovery towards a greater horror. But our Cyclopsed, fingers-missing madmen reappear and our campers hide – another prelude to the bloodshed that will take up the rest of the film. The tension slips before it has really gripped.

The only suggestion as to why and how the hideous threesome are as they are is given during the opening credits. Newspaper cuttings of a supposed deformed family of cannibals gives the illusion of myth, but just seeing their parking lot of abandoned cars and trucks reveals it is very much an urban legend. Schmidt hints that they have almost supernatural sensitivity – thus, one smells out Chris from under a car. To his discredit, Schmidt doesn’t really follow this through logically. Earlier, three of them fail to smell out any of the quartet hiding in the cabin. Their make-up is convincingly done – a cross between the more terrifying creations of Harryhausen and our own perception of people removed from humanity. Dream of a freak and at least part of it will have been re-imagined in this film.

The plot is simple – a car crash, our ‘victims’ hiking through the forest in search for help, meet the cannibals, murders gruesomely done one by one… But Schmidt’s best move is to not lace the film with extras. Although we learn little about the characterisation and motivation of those involved it hardly seems relevant in the context of a film which is really a visual feast of murder and mayhem.

If the acting is wooden (as it is usually is in this genre) that is dissipated by Stan Winston’s make-up design and creative effects. Elia Cmiral’s brooding score, all low strings and slashing chords, creates a sense of unease and tension and he uses music artfully to shock. It might not be all it could have been but the film does give a punch to the gut. But, don’t leave as the end credits roll – there is a surprise in store which suggests a sequel. Now where have I seen that before?

Marc Bridle

21/2

Return to Index