************************************************************** EDITOR’s CHOICE January 2003 **************************************************************

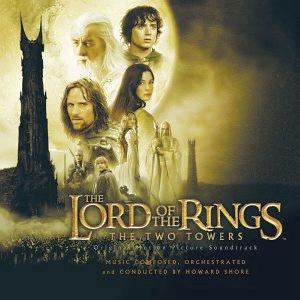

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers

Music composed by Howard Shore

Vocal solos by Emiliana Torrini, Hilary Summers, Isabel Bayrakdarian, Sheila Chandra, Elizabeth Fraser

Performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Voices, the London Oratory School Schola

OST/Internet Edition Enhanced Disc REPRISE/WMG SOUNDTRACKS 48419-2

Running time: 76:58

Crotchet Amazon UK Amazon US

Before entering into a proper critique, I want to address a distinct oversight in many reviews of the first two "The Lord of the Rings" films and their soundtracks. We read about the technical skill of Howard Shore's music, and consider the emotional outpourings of its drama, but what of the pivotal role music has in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth...

Among the central themes of Tolkien's work is a reiteration of a medieval cosmological concept known as the Great Dance, steps a universe must follow in relation to its context (the Great Chain of Being), with understanding to the parallels (the System of Correspondence) between our dance and the music we are supposed to follow. Fellow author Charles Williams observed that "All evil represents some violating of the steps," a belief that fuels Tolkien's plots. Like many before him, Tolkien set an eternal path--the "road that goes ever on"--as the stage for his particular characters. But the road needs context, the steps require a pace, and Tolkien found a literal, philosophical, and theological way of illustrating this. He chose Song.

Music provides a certain quality to storytelling, particularly in Tolkien's literature. On the surface, his lyrical texts provide a degree of realism. No civilized band of travellers leaves art completely behind. Who here goes on as little as a one-hour drive without thinking about music at least in passing? Some of us probably hum, whistle, or outright sing without any conscious effort. J.R.R. Tolkien likewise envisioned Hobbits as being particularly sophisticated in songwriting, harmonizing with their rather homely attitudes and countering any notion of them being fools. Wizards chant, and meditate. Elves, written as the ultimate musicians, are also quite civilized. Positive themes, plot points, and attitudes are all specifically introduced in verse. There is a pre-history here. In the broader view, this mirrors several key threads... Tom Bombadil personifies 'natural music,' his seemingly arbitrary inclusion in the stories actually reveals song for song's sake, in both the literal and philosophical senses. The author himself called Tom a spirit of pure science, as opposed to applied science; as such, Tom reveals the truth as well as the limitations of song on earth (again, both literally and universally), while Galadriel's speciality is the use of song itself.

In other books, the author portrays the realm of Iluvatar as being characterized by melodies, the Ainur sing, and Iluvatar Himself uses music to create and shape Middle-earth, although others, namely Morgoth, may distort the notes. Verses typically work against the villains in some fashion, be it a general sense of hope or two very direct confrontations with Sauron. When the corrupted do sing, they use discordant words or rhythms. It is no small matter that the villains of Middle-earth shy away from harmony in every sense of the word.

Tolkien considered music essential to his vision of Middle-earth, and he told his stories accordingly. I bear this in mind as I address Shore's "The Two Towers".

Having signed-up for e-mail notification via the "Fellowship of the Ring" album, a special offer for a US $30 "Internet only" limited edition arrived in my mailbox. I figured, "Hey, it's almost Christmas," and give into temptation. I received the album shortly thereafter in an uncharacteristically bulky package, on the Saturday before its official release. Inside the box is a pocket case bound in manufactured elf skin, accompanied by five glossy, two-sided movie cards. The handsomely produced wallet contains a thick booklet with beautiful (and occasionally whimsical) photographs, dry liner notes and new lyric texts of middling quality in one sleeve, and the music disc in the other. I quickly began listening...

"The Fellowship of the Ring" was a genial but at times needlessly hokey adventure score. "The Two Towers" is darker and more brazen, a marked improvement over its predecessor, recalling the great differences between the original "Star Wars" score and "The Empire Strikes Back".

Obviously, the various 'One Ring' motifs return, along with other "Fellowship" melodies that sometimes appear as bittersweet recollections. Though troublesomely louder, orchestrations broaden the scope of the musical narrative, bringing it closer to Tolkien's epic through more ethereal choruses and tinges of operatic mythology. Shore also adds magnificent thematic material, notably a fanfare for the race of Man, given sorrowful readings on a Hardanger fiddle, pride via the horns, or nobility in the full orchestra. Music for the tree-like Ents brings percussive rolls and a bassoon (owing something perhaps to John Williams' woodsy representations). Gollum receives his own practical treatment with a Hungarian dulcimer; however, the end credits 'Gollum's Song' is truly like a "Bond" ballad on downers. It is sad enough that Tolkien's classic verse is circumvented, but Emiliana Torrini's voice is like having glue down one's trousers--it sticks in a bad way. Gollum is pitiable, not pouty, and a character as memorable as he deserves equal representation.

What accessories does the Internet Edition soundtrack have to offer? Presumably to make more room for a bonus track, the nice-enough 'Farewell To Lorien' from the extended "The Fellowship of the Ring", the tracks 'The Uruk-Hai' and 'The Black Gate is Closed' are approximately 15 seconds shorter apiece than on the regular album. But enhanced features include downloadable maps and artwork, full lyric & poem texts, computer wallpaper, an interview with the composer (situated in a predictably hyperbolic electronic press kit), and the promises of a behind the scenes look at the scoring process and a music video.

Making Howard Shore's score for "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers" immensely rewarding is the almost relentless pursuit of drama, addressing the growing threat of the story's corrupted wills while shining rays of hope through that darkness. It does not match "Fellowship" for pleasantness (or unintentional goofiness), but it is a deeper, more focused listening experience.

Jeffrey Wheeler

4½

Return to Index