Curio Corner

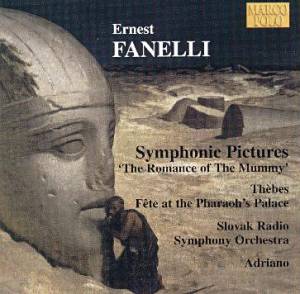

Ernest FANELLI (1860-1917)

Symphonic Pictures: 'The Romance of the Mummy'

Louis-Albert BOURGAULT-DUCOUDRAY (1840-1910)

Cambodian Rhapsody

Adriano conducts the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; (Recorded at the Slovak Radio Concert Hall, Bratislava in May 2000 and January 2001)

MARCO POLO 8.225234 [69:09]

Crotchet Amazon UK Amazon US

The conductor Adriano has built up a fine reputation for discovering (or re-discovering) opulent and colourful Late Romantic music and for his well-received Marco Polo film music albums – particularly those devoted to Georges Auric. This new release of music by the forgotten French composer Ernest Fanelli, whose patron was Pierné, would seem to straddle both genres. Not only does this effulgent material anticipate Respighi, Richard Strauss and Debussy (to mention just three composers) but it also points the way to the film music of the mid-20th Century – particularly that of Bernard Herrmann. Fanelli was regarded by many as too avant-garde. Listen to this music composed in 1883/6 (although not premiered until 1912, just one year before Stravinsky's Sacre du Printemps) and you will immediately hear why. As Adriano comments in his learned booklet notes:

"Already in 1883 Fanelli uses whole-tone scales, intervals of a ninth and picturesque harmonic and instrumental effects which later became trademarks of the Impressionists. Polytonality, uneven metres, unmodulated changes of harmonies, free ornamentation, the use of augmented triads and an overall non-relation to basic tonality can be found in Tableaux Symphoniques, perhaps the first example in French music history in which sound and instrumental colour become principal means of musical expression and in which a composer dares to transpose his purely sensorial impressions and detaches himself from absolute music and traditional romantic tone-painting."

Fanelli's Tableaux symphoniques d'aprčs Le Roman de la Momi, to give the work its proper French name, is presented here in two parts each with three movements. Briefly it concerns the fate of Tahoser an Egyptian girl who has fallen in love with Poëri a handsome young Hebrew. Ramses II the mighty Pharaoh is attracted to her too and resolves to have her at all costs. When Tahoser discovers that Poëri is in love with another woman, she languishes and becomes ill. She is healed by the mysterious prophet Moses who initiates her into the cult of Jehovah. Ramses manages to abduct Tahoser and becomes an enemy of the Jews leading to the oft-told events of the plagues, the exile and the parting of the Red Sea. Tahoser is crowned Queen of Egypt and discovered in Pharaoh's tomb by a 19th century archaeologist who falls in love with her mummy.

Part I entitled Thčbes is in three movements (tableaux). The sultriness of the first tableau, suggesting the stiffling heat of the streets of Thebes, impressed Ravel. The plaintive voice of a female slave (mezzo-soprano Lydia Drahosova) accompanied by two harps and tambourines, played behind the orchestra, was something of a novelty at the time. The second tableau is set on the banks of the Nile where preparations are afoot for the victorious return of the Pharaoh. The music turns from busy chatter to languorous sighing as Tahoser catches sight of the handsome young Poëri. The music here, nervous, edgy and full of yearning, underpinned by heavy ominous bass drum rolls, sounds incredibly like a Bernard Herrmann Hitchcock score. The final tableau of Part I depicts the triumphant procession of Ramses and anticipates Debussy's Images and, uncannily, the crescendo of approaching legions along the Appian Way in Respighi's Pines of Rome, although the atmosphere is undeniably Egyptian. The orchestral forces unleashed here are mighty indeed and it is advisable that you ensure the neighbours are out! This crushing march with huge repeated gong crashes and heavy bass drum rolls, like the tread of giant elephants, is only softened momentarily as Pharaoh espies Tahoser in the crowd. Again the music's cell-like patterns and extraordinary colourful orchestration suggest Bernard Herrmann. I have to warn that this movement tends to rather overstay its welcome and afterwards you could well be reaching for the Paracetamol.

Part II is again divided into three tableaux. Inside Pharaoh's palace Ramses is massaged by his slaves and entertained by naked girl jugglers. Not surprisingly, the music is exotic and sinuously sensuous. The second tableau is an extension of the scene with grotesque jesters joining in. The music is reminiscent of Rimsky-Korsakov but more often it is as advanced as Bartók or Stravinsky. At various times during these two movements I was reminded of several film music ideas: Ron Goodwin's Ascent/Descent of the Cable Car from Where Eagles Dare, the morse-code type motif used for by RKO-Radio for its radio mast and globe logo - and Bernard Herrmann's North by Northwest and Vertigo music, for instance. The growing passionate frenzy of the final tableau Chants triomphaux – Orgie is beheld with growing indifference as Pharaoh becomes more and more infatuated with Tahoser. He learns that she is the daughter of a high priest. The ladies of his court are racked by jealousy. The music here is majestic, decadent and ambiguously menacing and very avant-garde.

Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray's Rhapsodie cambodgienne of 1882 is much more of its time with straightforward melodies and harmonies. It is cast in two colourful nine-minute movements that incorporate Cambodian melodies and suggest the music of Balakirev or Rimsky-Korsakov. The opening movement commences in pastoral vein and then reaps the whirlwind as the Gods of Earth and Water combat to re-establish the land's fertility. The second part is devoted to bombastic celebratory music.

Vivid Technicolor music incredibly advanced for its day anticipating not only Respighi, Debussy, Bartók and Stravinsky, but film music of the mid-20th century – especially that of Bernard Herrmann. It might, at times, overstay its welcome but it is played with such vivacity and enthusiasm that serious criticism is disarmed. Great fun – but make sure the neighbours are out this is heavy-weight stuff.

Ian Lace

Return to Index