************************************************************** EDITOR’s RECOMMENDATION February 2002 **************************************************************

Giacomo PUCCINI (1858-1924)

Filmed Opera: Tosca

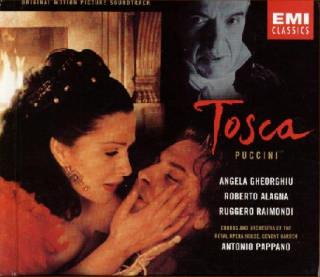

with Angela Gheorghiu as Floria Tosca; Roberto Alagna as Mario Cavaradossi and Ruggero Raimondi as Baron Scarpia.

OST; Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Tiffin Boys Choir, >Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden conducted by Antonio Pappano

EMI CDS 5 5713 2 [111:17]

"This shabby little shocker" was the non-too-complimentary label one contemporary critic attached to Tosca (first performed in 1900) the central second opera in Puccini’s sensationally successful run of three operas beginning with La bohème and culminating in Madama Butterfly. It is a very melodramatic work; the story would lend itself very well to an exciting and horrific screenplay. Puccini was a master of the theatre and of manipulating audiences with suspenseful, dramatic stories and strong characters and often tragic misused heroines. His music has a ‘filmic’ quality too, full of atmosphere and very evocative. ’Just two examples of what I mean from Tosca. First, the conclusion of Act I where Scarpia is gloating over the trap he has set for the jealous Tosca. He sings "Tosca, you make me forget God", as the cathedral choir sings a Te Deum while canons fire outside to signal the escape of the political prisoner, Angelotti. This is theatre on the grand scale. Then there is the atmospheric opening of Act III, set on the battlements of the Castel Sant Angelo just before dawn when Cavaradossi is due to be executed. A shepherd boy is heard singing in the distance, off stage, and then we hear the bells of countless churches resounding around the Eternal City, a magical evocation. On the strength of such imaginative writing, it is interesting to conjecture what Puccini might have achieved if he had lived through to the 1930s and beyond, and been persuaded to write for films.

This 2 CD set is a sumptuous production. It comes in the form of a hardback CD-sized book with the CDs tucked into the cover end papers. There are many illustrations taken from the film (reviewed by Marc Bridle below). Pappano directing Gheorghiu and Alagna seems to be cornering the market in the popular opera field and this is no exception – it is a resounding success. Gheorghiu is a convincingly feisty Tosca: gentle as she longs for her tryst with Cavaradosi in Act I Non la sospiri, la nostra casetta (Don’t you long for our little house), and then catty in her unfounded jealousy of her lover. In Act II she is first plaintive and pleading (Vissi d’arte – I lived for art. I lived for love) as she faces her tormentor, Scarpia and then viciously triumphant as she stands over his dead body. Alagna is her ideal Cavaradossi, virile and romantic in his 1st and 3rd act duets with her, and in his own romantic arias: E te, beltatde ignota – And you mysterious beauty (Act I) and E lucevan le stelle – And the stars shone (Act III); plus his wonderfully defiant outcry, "Victory, victory!" when he hears of Napoleon’s victory as Scarpia’s men torture him. Raimondi is quite brilliant as the ruthless, snide, lascivious Scarpia; his end of Act I aria, a startling study in malevolence and his Act II aria Già, mi dicon venal – Yes, they say that I am venal) quite chilling.

A wonderful production. Taken with the film, it forms an ideal introduction to this very approachable opera, full of drama and excitement and memorable melodies.

Below is a review by Marc Bridle of the actual film:

This brilliant, and at times devastating, film adds considerable flesh to the fine soundtrack released by EMI last month [EMI 7243 5 57173 2 0]. Early reviews of that set (in quite lavish packaging) have already placed it on an equal footing with EMI’s other long-famous Tosca, that of Maria Callas, now almost half a century old. It is frankly not quite that good, and indeed doesn’t surpass Sinopoli’s spellbinding Tosca for DG [DG 431 775-2] either, different as that is mood and drama. However, seen in a visual context it is an unforgettable experience.

Jacquot’s direction of this film is startlingly vivid, indeed it almost comes across as pseudo-documentary in style. He uses black and white, colour and grainy visual effects in a way which adds immeasurably to the intense drama and emotion of the on-screen acting, which even given the fact these are not screen actors is of an extraordinarily high level. The film opens with us in the recording studio – Pappano seducing his players with impassioned conducting – and we remain there for quite some time. The first we see of the major characters is in close-up black and white recording at the microphone, but this quickly dissipates and we then experience them in the opulence of colour and the settings.

It is noticeable that Jacquot concentrates the studio intrusions to the first and third acts the second remaining almost entirely stage bound. This proves revelatory – rarely have I ever been so gripped by this act, the interplay between Angela Gheorghiu’s Tosca and Ruggiero Raimondi’s Scarpia [left] spellbinding in its intensity. Visually, this is also the most startling act – with hovering overhead shots and swirling camera angles. An extraordinary moment is Scarpia sat at the dinner table plotting his seduction of Tosca, his face mirrored lingeringly in the blade of his knife – an appropriate irony given that it is this very knife with which Tosca will finally kill him. The costumes and sets through out this act are also finely conceived: Tosca, dressed in a long red dress in sharp contrast to the black of Scarpia, yet with the power and sexuality strikingly evident, the fireplace of the Palazzio Farnese near which so much of the action between the two takes place, and the subtle use of candle light to off set the darkness: all are magnificent.

The acting of the three principal characters exceeds expectations. Certainly, Gheorghiu is no Callas (her facial expressions can occasionally seem contrived) but there is undeniable passion in her assumption of the role. She is at her best with Scarpia, quite chilling in fact, but there is also wonderful tenderness in her scenes with Cavaradossi – her off screen husband, Roberto Alagna.

Their kisses are smouldering, the eye contact between them rekindling the kind of memories one remembers from Bogarde and Bergman in Casablanca. Alagna, ruggedly handsome in Act I, looks genuinely pain-stricken in Act II, his face be-smeared with blood from the bolts etching into his temple during his off stage torture (although not that off stage, it should be said, in this version). When the wounded Alagna sings ‘Vittoria! Vittoria!’ it is with quite thrilling tone, and much more intensely than we are used to in the opera house. The mood is exact – threatening yet heroic. Alagna perhaps lacks the depth of tone for this role which Domingo brought to it (he can occasionally seem too bright) but it is still utterly memorable.

In a different league altogether, however, is the Scarpia of Raimondi. Gheorghiu has been quoted as saying that she found his acting unbelievably intense, frighteningly so – and this certainly seems to be case. The only one of the main singers with a credible film history (having appeared in films by Alain Resnais) he has a natural on screen personality. His Scarpia is gripping – both vile and frail, both human and inhumane. It is sung magisterially.

Act III takes us back into the studio – and back to black and white, with grainy images of the Castel San Angelo interspersed with scenes of Papanno and the orchestra. An over-angelic James Savage-Hanford sings the role of the shepherd, with lofty camera angles highlighting sheep lit like lanterns. Parts of this act take a regressive approach to the film’s action – scenes from earlier in the film are here played in reverse, such as Tosca placing flowers at the statue of the Archangel or Scarpia moving back into the darkness of his rooms at the Palazzio. The ending has cumulative power – with Tosca throwing herself off the parapet in more realistic fashion than you would encounter in the opera house

The main achievement of this film is that it somehow maintains the theatricality of this powerful opera. It is at times unimaginably intense, an opera about violence which isn’t overtly violent to watch. It is not in any real sense an analytical film – it is filmed exactly as the libretto directs – but takes as its focal point the drama and lyricism of its three protagonists. This is a film where the voice is the star – and even given the diversity, and beauty, of the staging it remains so. Jacquot makes no concessions – and his cast match his vision well nigh perfectly. It is certainly one of the finest filmed versions of an opera I have ever seen.

Marc Bridle

[no rating]

Post scriptum: The bad news for UK film-goers is that this film is scheduled for UK release on 5 April 2002 at the Chelsea Cinema on the King’s Road. Major metropolitan centres will follow thereafter.

Return to Index