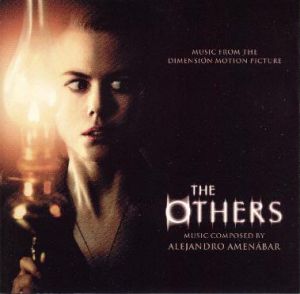

Alejandro AMENÁBAR

The Others

Music from the film performed by The London Session Orchestra conducted by Claudio Ianni

SONY SK 89705 [41:08]

The Others, a psychological chiller, starring Nicole Kidman and set in Jersey at the end of World War II has been scored by film’s writer and director. The credit for the inventive and imaginative orchestrations has to be shared amongst a whole team of orchestrators: Xavier Capellas, Claudio Ianni (who also draws a spinetingling atmospheric performance of the music from the contract players of the London Session Orchestra), and Lucio Godoy as well as Amenábar himself.

"Distorted Reality" is billed in the booklet as having contributed sound effects. These amount to (just) a newish spin on the usual screechings and poundings that inhabit the horror genre scores. The difficulty I find with this score is that after an impressive start when I began to think I would cheer and award it one of my Editor’s Recommendations, perhaps even my choice of the Month, the majority of the central tracks wondered off into too-familiar territory. Admittedly these cues are well played and recorded with plenty of gusto and much oomph in the bass; and, at times, the material is impressively terrifying and will, no doubt, enhance the on-screen images no end, but – well we’ve visited this stuff too many times before.

So, to the positive elements of this score which are laid out immediately in the opening tracks. 'The Others' begins imaginatively with fluttering, then eerie, yet almost pastoral figures that are redolent of the Impressionist music of Debussy and Ravel with a dash of Ralph Vaughan Williams. The music mixes the enigmatic and vague and ghostly, with material suggesting child-like innocence. The orchestration intrigues: harp, harpsichord, celeste, solo violin etc with ghostly, mid-distanced wordless chorus. This material is developed and becomes more sinister in the bass strings and woodwinds in the following cue ‘Wakey, Wakey’. In ‘Old Times’ slow chiming echoes prevail in unsettling glassy music that has a central section of infinite sadness. From then on until recapitulation in the final tracks, we have the usual ghostly thumpings relieved only occasionally by the pathos of an odd cue like ‘Charles’.

An album that begins intelligently and imaginatively but cannot sustain its early promise

Ian Lace

Mark Hockley adds:-

That rare breed, the director who composes his own score, is a fascinating creature. Able to envision his film on multiple levels, devising scenes specifically for the music he will create (sometimes it already exists and the scene is tailored for the score), there are very few examples of the composer/director, but even so, these multi-talented individuals have still produced some truly outstanding work (Frank LaLoggia’s Lady in White (1988), John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) for instance). So how does Alejandro Amenabar’s efforts rate in comparison? The film itself, if the trailer and the reviews are anything to go on, looks and sounds a very fine production, but with this extremely atmospheric score I find myself caught in two minds concerning its value as a CD release. And let’s be clear, that is what I’m reviewing! On the one hand, it is undoubtedly a strong piece of dramatic film scoring; the strident bursts of cacophony on ‘They are Everywhere’ and the ominous ‘I Do Believe It’ testify to its cinematic quality. And yet, it’s not a particularly easy listen. Atmosphere is the key word and Amenabar delivers this with skilled precision, but by its very nature this is a remote, coldly unsettling piece that is hard to appreciate on a simply conventional musical level. Despite this, some of its many eerily effective cues like ‘Give Me the Keys!’ and ‘Sheets and Chains’, where dissonant strings and growling brass become undeniably harrowing, are to be admired if only because they achieve so expertly what they set out to do.

In summary, this is ‘haunted house’ music that walks a well-trodden path, but is nonetheless very accomplished and will no doubt work a treat in the film itself. Probably its biggest demerit is its lack of a memorable, emotional theme. Indeed, it is relentlessly dark and disturbing with very little warmth, although towards the end, ‘A Good Mother’, goes some way to off-setting this feeling of pervasive gloom as it concludes with a melodic, hopeful flourish. But while it is perhaps less accessible as purely a listening experience this is without doubt admirable film music in its most literal sense and certainly deserves credit for achieving an almost palpable sense of dread and disquiet. The only question mark is whether anyone will want to return to it without the benefit of the images it was written to accompany.

Whatever the case, there is one word that sums up this score perfectly. Creepy.

Mark Hockley

Return to Index