|

|||||||||

Music Webmaster

Len Mullenger:

Len@musicweb.uk.net

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

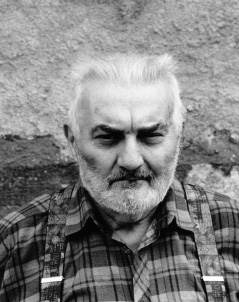

Franco Donatoni - (1927 - 2000) by David Wright

Image courtesy of Max Nyffeler http://www.beckmesser.de © Max Nyffeler

Franco Donatoni wrote glorious, sparkling music in his own avant-garde style.

He was a man of contradictions. He did not always value his work and yet it is music of quality with scintillating sound. It is music of vision.

Franco had a marvellous sense of humour and yet it would be lost on many people. He was a very funny man and yet he suffered many years of depression. In post-war fascist Italy there were few opportunities to learn music and very few teachers of any purport. As a result, composing music was fraught with problems.

He was born in Verona in 1927. His father was a civil servant and considered that his son should go into banking even if that meant starting as a humble bank clerk. But, in Italy, even this respectable job did not earn much money and so young Franco was encouraged to take up the violin to earn extra cash. He played in the Verona Arena Orchestra.

He was a lonely child. On Sunday afternoon walks he would imagine music and regret that the mechanics of writing it down was beyond him. And, as we have said, it was very difficult to obtain decent music tuition.

It was the great Petrassi that was Franco's first encouragement. But the young student was interested in other aspects of music. He would talk about how one lives with music as someone would talk about how one would live with a disease or a handicap. He felt that people going to concerts all dressed up with the orchestra in their tails was a convention and tradition that made no sense. He would say that one goes to a concert to hear music not to admire someone's clothes or social standing. He spoke of the emotional high at a symphony concert and how the audience in that environment were transported but as soon as they left to go home what did they have but a memory. How does one live with music was Donatoni's question.

The next great influence on his life was Bruno Maderna another composer of great originality, but then there were so few composers in Italy that the claim to originality could be made quite easily. Franco attended the Summer School at Darmstadt in 1954 and encountered Stockhausen and John Cage. While he had some admiration for Stockhausen he would say that he was always perfecting his own ego.

What I shared with Donatoni was this conclusion namely that composers with big egos were not really composers at all but showmen and they merely wanted to advance themselves, not music. This is why Donatoni said, "I am not an artist but an artisan." I know exactly what he means. The British composer, Francis Routh, has often said, "I want to make music not money." Humphrey Searle would say, 'A composer must know his skill but write what he wants to write. If he imitates another he will not be original. He should not want to make a name for himself. If he does he should take up politics or something non-aesthetic."

Donatoni experimented briefly with serialism and admired its discipline, writing some piano works in this most demanding of styles. He took an interest in John Cage for a while since he felt that traditionalism was strait-jacketing music. But he also found that Cage's style and philosophy was so negative that it dragged him down as well. His score Black and White for two pianos have no precise notes, durations and dynamics. His Composition in Four Movements (1955) is based on permutations of various rhythms. But this chance music a la John Cage was so contrary to the concept of composition.

In the mid-1960s Donatoni was still searching for a means of original expression in music. In 1967 he took eight bars of the second piano piece of the Five Pieces op 23 by Schoenberg and wrote an extensive piece around it. He analysised the fragment and rewrote it every way he could . He got inside the piece and got everything out of it that anyone could. What we have is a detailed, in-depth study in which no stone is unturned. It is a colourful piece in a quasi-concertante style, a marvellous experiment of what you can do with merely eight bars of music. There is a clarity of texture in a well-developed musical argument. At times the music is agitated. The tension builds up dramatically. Donatoni said, "There is something elusive about Schoebnberg's notes." The piece, Etwas ruhiger im Ausdruck is scored for flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano. As Reginald Smith Brindle points out, "It is a tour de force of technical contrivances having brilliant qualities, particularly in its texture and austere monastic tone.

The 1960s were not happy for Donatoni. Italy had nothing to offer musically. The 1970s were even worse. He lived on pills for a while and the tragic death of Maderna in 1973 devastated him. As he believed that music should never be egotistical and, therefore, not a means of self-expression he did not want to show his feelings. To him music was absolute and while it had to have expression it was not to be self-expression or egotististical "You cannot really write your life story in music because words express 'self' best whereas music expresses something beyond words," he would say.

His Duo per Bruno is, however, his mourning for Maderna. It is a homage. There are moments of exceptional poignancy from the two violins and the sparingly used percussion suggests heartbeats. The ringing of the bells suggests a cortege and the two pianos and two harps are employed to portray confusion caused by grief. The brass depict a controlled anger. Here is Donatoni paradoxically hiding his feelings and not wanting to wallow in self-indulgence. The string collage towards the end is very impressive. Written at the time of the composer's darkest days and his deep depression the concluding snarling brass rasps angrily and the bells toll.

This is cerebral, intellectual music and not for the musically squeamish.

And it is unconventional. Yet, eventually, Donatoni had to succumb to the conventional and accept that symphony concerts had a mode of dress and behaviour and that the concert hall had a reverence about it. Yet in the 1970s he said that in composition he could do no more and so became a copyist. His wife was troubled by his decision and tried to encourage him to take up composition again. Gradually, he changed and moved out of his crippling depression and found his feet. He found that there were students who wanted the benefit of his experience and who had been influenced both by his music and his writings. He took on some of these students.

They all found him to be an energetic teacher who enthused about many things even the dull mechanics of music. He was a strict master and did not approve of students using the piano to compose. Indeed, he expected a lot from his students. And he was tough. Yet he was kind and generous. He had both an enormous presence and smile. He was a big man and would travel around on his bicycle. He had begun to compose again. He had a new lease of life. His music became confident, euphoric and melodious which still retaining his 'modern' style. His music had a compulsive wit and a delicate virtuosity and yet it was never weak. His music was never extreme in tone. Rather, it was a strong mezzo forte throughout generally.

He loved to be provoked. People would say that he could not write for such an instrument or combination of instruments and he would rise to the challenge and do so. As he now had a circle of musicians around him, he would write for small chamber ensembles so that they could play his music. "Writing for small groups can be very gratifying as you are writing for friends and people you know who want to play your music," he would say. He would also refer again to the traditional position of the symphony orchestra and comment that a composer would spend a year or so writing for a large orchestra and hope that it would be played. And if it were, it may be played just once and forgotten.

Refrain is a magnificent chamber piece. It includes a guitar, marimba, viola, double bass, harp, clarinet and bass clarinet and produces an euphonious sound, effortless and very exciting. It has the recurring thrill of sudden bursts of sound and the concertante style of the music, particularly the marimba, adds to the quality of a wonderfully virtuoso piece. I have often thought that John Adams has imitated this piece very often particularly in the dances from Nixon in China. The work is less severe than others and ends almost in E major almost a Mediterreanean vigour. The sheer brightness of the music is a delight.

Cloches for wind, percussion and pianos is another superb and striking piece. It has rich textures and is very thrilling musically. There is the usual Donatoni toughness and density but also that lightness of touch. It is an unforgettable piece. And that cannot be said about many pieces.

He did not write for voices until late in his career. In 1993 he wrote a song An Angel within my Heart for soprano, two clarinets and string trio to words by his wife, Susan Park. Again it is a work of high quality throughout.

Donatoni regarded himself as Veronese rather than an Italian and yet there are those who believe that he is more a central European. He had some great ideas such as the view that a composer does not create, he transforms. As with his musical treatise on eight bars of Schoenberg he put forward the idea that detailed material could be so reworked that you could never run out of it. He had a tremendous wit and his work is full of surprises. He is a modern day Haydn.

Donatoni has come a long way since his early days studying at the Verdi Conservatory in Milan (1946-8)and the Martini Conservatory in Bologna (1948-51) and with Pizzetti in the Academia Saint Cecilia in Rome. Pizzetti was a real traditionalist and hated anything modern. If music was not in a key signature and did not have melody and traditional harmonies it was not music at all. How naive and backward can one be? Donatoni's first works were reasonably conventional with four string quartets, a Sinfonia for string orchestra, Doubles for harpsichord and Doubles Two for orchestra and then came the Schoenberg piece, one of Donatoni's "de-composed "works..

Donatoni died on 17 August 2000. He leaves a wife and two sons. But he has also left a legacy of a new musical language and has paved the way with Luigi Nono for a new renaissance in Italian music. How long must we wait until this original genius is recognised?

Copyright David C. F. Wright . 20 August 2000.

The author wishes to thank Reginald Smith Brindle for his help in the study of Donatoni over many years

Return to:

Classical Music on the Web

These pages are maintained by Dr Len Mullenger.

Mail me.