|

Page

33

|

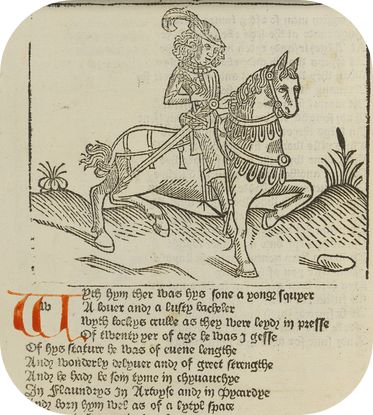

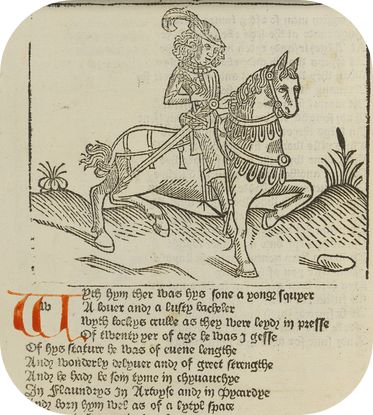

| Conclusions The ability to print books was revolutionary. For the first time it would allow the democratization of knowledge and this ready availability of knowledge led to the reformation. In 1440 Gutenberg was only able to produce a few hundred copies of his bible but most of the population were not able to read then anyway. But by 1500 printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than twenty million volumes. In the 16th century, with presses spreading further afield, their output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies. Galileo in the 1630s remarked “when he was young one could read everything there was to know, but by the time of his quote, one could no longer know everything there was to know, as new books were being written faster than one could read.” The Englishman William Caxton went to Cologne to investigate printing and in 1496 produced some books in Latin. He then established a print shop in Ghent publishing English and French texts and as mentioned earlier he produced the first text in English - Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye "A Collection of the Histories of Troy“ which was actually a translation from the French. Printing was a gamble because the process was inflexible. You needed to estimate how many copies you might sell. Print too many on expensive paper and you went bankrupt. Caxton was fortunate in having a royal Patron, the Duchess of Burgundy known as Margaret of York, daughter of Richard Neville, the Third Duke of York who provided financial security. In 1476 Caxton brought his printing press to Westminster and printed the Canterbury Tales and for the 2nd edition of 1483 he added woodcuts to make it visually attractive. The language was Middle English.

|