|

Page

12

|

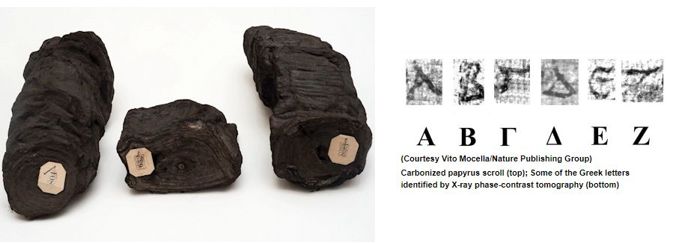

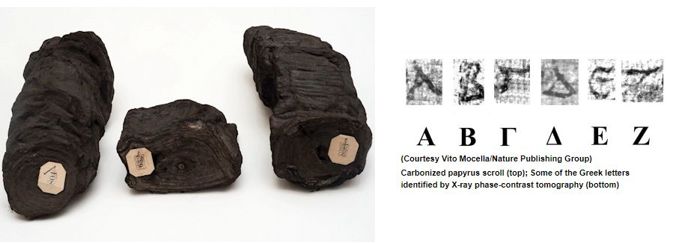

| Scrolls at Pompeii and Herculaneum were buried

in hot volcanic ash after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. They were charred

by the heat and carbonised. Oddly this has preserved them. They were discovered

in the 18th century but not recognised for what they were. Some early archaeologists

thought they were charcoal and actually used them as logs on fires. There

were attempts to unroll them. It could take up to four years to unroll just

one and you ended up with thousands of carbonised fragments that looked

just like cinders. In the last couple of years, Brent Seals, of Kentucky

university, used the technique X-ray phase-contrast tomography (XPCT)

to try to look inside the scrolls without any physical contact – virtual

unwrapping. This is like a body-scan where you can look at different layers

of, say, the brain. This technique does not actually read the ink as that

was made from soot and appears the same as the carbonised scroll. Instead

it detects the indentations made when the letters were applied to the scroll.

This tomography requires very high energy particles produced by the particle

accelerator found in a synchrotron machine used for research into Physics

and, in particular, the hope of achieving fusion reactions such as those

that energise the sun. This would give the world abundant free energy. It

always seems to be 20 years away! The researchers had to first overcome

the reluctance of conservators to hand over the scrolls and then beg scientists

at Harwell’s Diamond Light facility for synchrotron time! However, much greater success was obtained with a different scroll from Ein Gedi (pr. en gedy) near the dead sea. The ink had been made differently and has traces of metals in it so could be more easily visualized. What they see are not like photographs but are computer generated pictures using immensely complicated algorithms. They were able to read the text on five turns of the scroll There were 35 lines of text in two columns, composed of Hebrew letters just two millimeters tall. Israeli researchers identified the text as the first two chapters of the Book of Leviticus, dating to the third or fourth century A.D. It was a hugely significant find for biblical scholars: the oldest extant copy of the Hebrew Bible outside of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and a glimpse into the history of the Bible during a period from which hardly any texts survive. This is a terribly exciting new area which may eventually lead to the recovery of the lost work of authors such as Sappho and Lucretius among others. But, of course, this technique will not just be useful for ancient scrolls. Libraries all over the world house ancient, badly damaged books - the contents of which have been previously inaccessible.

|